Carew Tower

Carew Tower is a 49-story, 574-foot (175 m) Art Deco building completed in 1930[7] in the heart of downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, overlooking the Ohio River waterfront. The structure is the second-tallest building in the city, and it was added to the register of National Historic Landmarks on April 19, 1994. The tower is named after Joseph T. Carew, proprietor of the Mabley & Carew department store chain, which had previously operated on the site since 1877.

| Carew Tower | |

|---|---|

| |

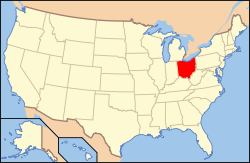

Location within Ohio | |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Location | 441 Vine Street Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Coordinates | 39.1007°N 84.5132°W |

| Construction started | 1927 |

| Completed | 1930 |

| Cost | US$33 million |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 190 m (623 ft) |

| Roof | 175 m (574 ft) |

| Top floor | 171.3 m (562 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 49 |

| Floor area | 128,000 m2 (1,377,780.5 sq ft) |

| Lifts/elevators | 14 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | W.W. Ahlschlager & Associates Delano & Aldrich |

| Developer | John J. Emery |

| Main contractor | Starrett Investment Corp. Col. William A. Starrett |

Carew Tower-Netherland Plaza Hotel | |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 82003578 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | August 5, 1982 |

| Designated NHL | April 19, 1994 |

| References | |

| [1][2][3][4][5][6] | |

The complex contains the Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza (formerly Omni Netherland Plaza), which is described as a fine example of French Art Deco architecture.[8] The hotel's Hall of Mirrors banquet room was inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[9]

Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza is a member of Historic Hotels of America, the official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[10]

The tower remained the city's tallest until the completion of the Great American Tower at Queen City Square on July 13, 2010, rising 86 ft (26 m) higher than Carew Tower. Previously, Cincinnati had been one of the last major American cities whose tallest building was constructed prior to World War II.

History

Carew Tower was designed by the architectural firm W.W. Ahlschlager & Associates with Delano & Aldrich and developed by John J. Emery. The original concept was a development that would include a department store, a theater, an office accommodation, and a hotel to rival the Waldorf-Astoria. Emery took on as partner Col. William A. Starrett (Starrett Investment Corp.) and Starrett Brothers, Inc. as general contractors.[11] The building is widely considered to be an early prototype of an urban mixed-use development, a "city within a city". New York City's Rockefeller Center, built around the same time, is a more famous example of this concept. The Hotel Emery and an office block belonging to Mabley & Carew were demolished to make the site available for construction.

Construction began in September 1929, just one month before the stock market crash on October 24 that triggered the Great Depression.[12] Because of this, construction was continued on a modified plan.[13] Art deco themes can be found throughout the building, particularly in the metalwork and grillwork of the elevators and lights. Locally sourced inlaid Rookwood Pottery floral tiles adorn the east and west entrances of the building.[14] Sculpture on the exterior and interior of the building were executed by New York City architectural sculptor Rene Paul Chambellan.

Eighteen Louis Grell murals can be found throughout the Hilton Netherland Plaza Hotel on the bottom floor. Ten wall-to-ceiling murals can be found in the hotel's original lobby, now the Palm Court, four Greek Themed murals in the Continental Room and two above the side entry staircase are the work of muralist and painter Louis Grell. The ten murals in the Palm Court represent the recreation and it is believed that the artist representations of Carew Tower can be found worked into each background by Grell. The staircase mural says "Welcome Travelers" and the four in the Continental Room represent the four seasons of the year. The massive 90 foot long Apollo Gallery boost another "Apollo on Chariot" mural and a large "Hunt of Diana" mural by Grell. All murals are believed to be oil on canvas.

The total cost of the building was US$33 million, which at that time was an enormous sum of money. It took crews only 13 months to complete the construction, working 24 hours a day and 7 days a week.[12]

Through the 1930s the Netherland Plaza Hotel was run by hotel industry pioneer Ralph Hitz's National Hotel Management Company.[15]

From 1930 until 1960, Carew Tower was the home of the Mabley & Carew department store.

From 1967 to 1980, Carew Tower and the neighboring PNC Tower, then called the Central Trust Bank tower, were featured in the opening and closing credits of the daytime soap opera The Edge of Night, since Cincinnati was the stand-in for the show's fictional locale of Monticello. Procter & Gamble, the show's producer, is based in Cincinnati.

From 1978 to 1982, it was also featured in the opening and closing credits on the sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati, although the show was produced in Hollywood.

The building is home to a mixed group of tenants, including a shopping arcade, Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza, and offices. Visitors can access the observation deck located on the 49th floor.[16] On a clear day, visitors can see for miles in all directions, and three states (Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio). Because of its architectural standards, as well as its identity with the city's heritage, Carew Tower was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1994.

The building was originally designed with three towers: the tallest housing offices, the second the hotel, and the third serving as a parking garage which had an elevator rather than traditional ramps for access. The third parking tower was demolished in 1980 due to corrosion from road salt. There was also a turntable for vehicles to assist in pointing delivery trucks in the right direction. The system has since been dismantled.

Statistics

- 9 miles of brass piping

- 15 railroad cars full of glass

- 37 miles of steel piping

- 40 railroad cars full of stone

- 60 miles of floor and window molding

- 60 railroad cars full of lumber

- 4500 plumbing fixtures

- 5000 doors

- 8000 windows (upon its completion in 1931)

- 15000 tons of structural steel

- 4 million bricks in the outer structure

Gallery

Carew Tower, the second tallest building in Cincinnati, is an example of French Art Deco.

Carew Tower, the second tallest building in Cincinnati, is an example of French Art Deco. View of Carew Tower from Tower Place atrium

View of Carew Tower from Tower Place atrium The elevator lobby of Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza displays Art Deco style with original postal drop box

The elevator lobby of Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza displays Art Deco style with original postal drop box North side view from the observation deck.

North side view from the observation deck.- Taste of Cincinnati, as seen from the observation deck

References

- "Carew Tower". CTBUH Skyscraper Center.

- Carew Tower at Emporis

- Carew Tower at Glass Steel and Stone (archived)

- "Carew Tower". SkyscraperPage.

- Carew Tower at Structurae

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- CLEE25 (2013-12-22). "Carew Tower Observation Deck". Cincinnati USA. Retrieved 2016-12-22.

- McCarty, Mary (Jul 1983). "Cincinnati: The City for People with Big City Tastes and Hometown Hearts". Cincinnati Magazine Jul 1983. p. 66. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- Morris, Jeff (Jun 8, 2009). "Haunted Cincinnati and Southwest Ohio". Arcadia Publishing. p. 92. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- "Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza, a Historic Hotels of America member". Historic Hotels of America. Retrieved January 20, 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Painter, Sue Ann (2006). Architecture in Cincinnati: An Illustrated History of Designing and Building an American City. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0821417002.

- Schrage, Robert (Jul 1, 2006). "Along the Ohio River: Cincinnati to Louisville". Arcadia Publishing. p. 12. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- Hoevener, Laura (2010). Adventures Around Cincinnati. Hillcrest Publishing Group. p. 25.

- Federal Writers' Project (1943). "Cincinnati, a Guide to the Queen City and Its Neighbors". p. 177. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- Cincinnati Enquirer Newspaper, 11 May 1937, Pg. 7; https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/99498652/ Retrieved 08 March 2018

- Smith, Steve; et al. (2007). "Around Town: How to Decode Cincinnati's Many Motorways". Cincinnati USA City Guide. Cincinnati Magazine. p. 12. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carew Tower. |