Carcharomodus escheri

Carcharomodus escheri, commonly nicknamed the serrated mako shark or Escher's mako shark, is an extinct lamnid that lived during the Miocene. It has been formerly thought to have been the transitional between the broad-toothed "mako" Cosmopolitodus hastalis and the modern great white, but is now considered to be an evolutionary dead-end with the discovery of Carcharodon hubbelli. Fossil examples have been found along northern Atlantic coastlines and in parts of Western and Central Europe.[1][2]

| Carcharomodus escheri | |

|---|---|

| |

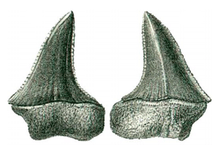

| Drawing of holotype tooth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Lamnidae |

| Genus: | †Carcharomodus |

| Species: | †C. escheri |

| Binomial name | |

| †Carcharomodus escheri (Agassiz, 1843) | |

Etymology

Carcharomodus is derived from the Ancient Greek κάρχαρος "kárkharos" meaning "jagged", όμοιος "omoios" meaning "similar", and δόντι "donti" meaning "tooth". The name was combined with the genus Carcharodon in reference to the similarity of C. escheri's dentition with that of the modern great white shark.[1]

The species name escheri is named in honor of Escher.

Thus, the species name literally means "Escher's similar to Carcharodon tooth".

Description

C. escheri teeth have been found around northern Atlantic coastal plains of North America, and in Western and Central Europe, with teeth being most common during the Late Miocene-Early Pliocene. Some teeth assigned to the synonym Isurus escheri has been reported in parts of the Pacific Rim including Australia and Peru, but these occurrences now represent a different taxon yet to be evaluated. With tooth size ranging up to 1.6 in (4.2 cm), C. escheri is estimated to have a body length of 13 ft (4 m).[1]

Teeth

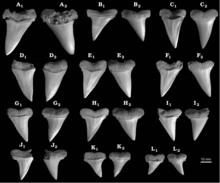

C. escheri teeth share resemblance to those of Isurus, Cosmopolitodus hastalis, and Carcharodon to some extent. Adult anterior upper teeth measure 2.7-4.2 cm and have an average angle between root lobes of 135°. All teeth possess lateral cusplets and crenulated and irregular faint serrated cutting edges, comparable to the edges of emery paper. C. escheri teeth are dignathically heterodontic with pointed and narrow lower teeth for grasping prey and broader blade-like upper teeth for cutting flesh, suggesting an intermediate diet between Isurus and Carcharodon/Cosmopolitodus.[1]

Size

In a 2014 study by Kriwet et al., The size estimates of C. escheri were made based on MNU 071-20 and assuming the species' relation to the modern great white. Using the formula from Gottfried et al. (1996), which bases on the ratio of the upper A2 tooth (the upper A2 tooth in this study's possession was 4.2 cm), a total body length of 3.81 m is calculated. When using an Carcharodon spp. based formula from Shimada (2001), the total body length is calculated to be 3.82 m, nearly identical to the Gottfried et al. (1996) formula. Another one of Shimada's (2001) formulas that was based on Isurus spp. was also used, which calculated a slightly smaller length of 3.67 m. Another formula by Gottfried et al. (1996) was also used, which bases on the size of the vertebral centra. With MNU 071-20's largest preserved vertebral centrum having a diameter of 77.7 mm, a total body length of 4.5 m is calculated. Based on these calculations, the study concluded the average total body length of 4 m. However, larger teeth have been found by others, and one of the largest recorded ones, which measures 5 cm, is calculated to come from a 5 m individual. With average great whites reaching lengths of 3.5–4.1 m (11–13 ft) for males and 4.5–5.0 m (14.8–16.4 ft) for females, C. escheri probably grew similar sizes to it.[1]

Taxonomy and Evolution

Taxonomic History

The C. escheri holotype tooth was first placed by Agassiz (1843) in the taxon Carcharodon escheri. However, on an earlier page and figure in the same publication he named a pathological tooth of the same species Carcharodon subserratus.[3]

In 1927, Leriche revised the taxon as a variation Oxyrhina hastalis var. escheri.

In 1961, Kruckow deemed the shark as a subspecies rather than a variation of the then Isurus hastalis and renamed it as Isurus hastalis escheri.

By 1969, van den Bosch re-elevated its status from subspecies to species under the name Isurus escheri.

A study in 2006 by Cappetta concluded that C. escheri is closely related to the modern great white and moved the taxon back to the genus Carcharodon.

In 2014, the discovery of MNU 071-20, the first known disarticulated and partially complete skeleton of C. escheri, led to the conclusion that it is a distinct genus from Carcharodon/Cosmopolitodus and erected the genus Carcharomodus.[1]

In 2018, Kent called the species Carcharodon subserratus in a review of sharks from the Calvert Cliffs, deeming Carcharodon escheri a junior synonym and arguing the species shares more similarities with C. hastalis than with Isurus and the creation of a monotypic genus to encompass it was unwarranted.[3]

Evolution

C. escheri teeth has some intermediate traits between Isurus and Carcharodon. Due to this, it has been speculated in the past to be the transitional species between the great white (Carcharodon carcharias) and the ancient makos (Cosmopolitodus hastalis). However, a study by Ehret et al. (2012) pointed out that C. escheri is restricted only to the northern Atlantic and Europe, while both Cosmopolitodus hastalis and Carcharodon carcharias were cosmopolitan, and that it went extinct much earlier before the appearance of Carcharodon carcharias suggesting that the intermediate features were simply a result of convergent evolution. The discovery of Carcharodon hubbelli, which showed stronger transitional features between the two sharks but also filled the missing time periods further supported this claim.[2]

Carcharomodus escheri is now believed to be one of the two direct descendants of the narrow-form Cosmopolitodus hastalis, the other being the hooked-toothed mako.[2]