Capsian culture

The Capsian culture was a Mesolithic and Neolithic culture centered in the Maghreb that lasted from about 8,000 to 2,700 BC.[1][2] It was named after the town of Gafsa in Tunisia, which was known as Capsa in Roman times.

| |

| Geographical range | North Africa, possibly East Africa |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic – Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 8,000 – c. 2,700 BC |

| Type site | El Mekta |

| Major sites | Medjez II, Dakhlat es-Saâdane, Aïn Naga, Khanguet El-Mouhaâd, Aïn Misteheyia, Kef Zoura D, El Mekta. |

| Preceded by | Iberomaurusian |

| Followed by | Libyans |

The Capsian industry was concentrated mainly in modern Tunisia and Algeria, with some lithic sites attested from southern Spain to Sicily. It is traditionally divided into two horizons, the Capsien typique (Typical Capsian) and the Capsien supérieur (Upper Capsian), which are sometimes found in chronostratigraphic sequence. Sometimes, a third period, Capsian Neolithic (6,200-5,300 BP) is also specified. They represent variants of one tradition, the differences between them being both typological and technological.[3][4][5]

During this period, the environment of the Maghreb was open savanna, much like modern East Africa, with Mediterranean forests at higher altitudes.[6] The Capsian diet included a wide variety of animals, ranging from aurochs and hartebeest to hares and snails; there is little evidence concerning plants eaten.[7][8] During the succeeding Neolithic of Capsian Tradition, there is evidence from one site, for domesticated, probably imported, ovicaprids.[9]

Anatomically, Capsian populations were modern Homo sapiens, traditionally classed into two variegate types: Proto-Mediterranean and Mechta-Afalou on the basis of cranial morphology. Some have argued that they were immigrants from the east (Natufians),[10] whereas others argue for population continuity based on physical skeletal characteristics and other criteria.[11][7][11][12]

Given the Capsian culture's timescale, widespread occurrence in the Sahara, and geographic association with modern speakers of the Afroasiatic languages, historical linguists have tentatively associated the industry with the Afroasiatic family's earliest speakers on the continent.[13]

Nothing is known about Capsian religion, but their burial methods suggest a belief in an afterlife. Decorative art is widely found at their sites, including figurative and abstract rock art, and ochre is found coloring both tools and corpses. Ostrich eggshells were used to make beads and containers; seashells were used for necklaces. The Ibero-Maurusian practice of extracting the central incisors continued sporadically, but became rarer.

The Eburran industry which dates between 13,000 and 9,000 BC in East Africa, was formerly known as the "Kenya Capsian" due to similarities in the stone blade shapes.

Gallery

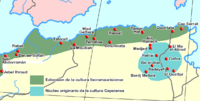

The main sites of the Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures in north Africa

The main sites of the Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures in north Africa.png) A Capsian ostrich-egg bottle

A Capsian ostrich-egg bottle.png) Typical Capsian burial (Tunisia)

Typical Capsian burial (Tunisia)

See also

- Ifri n'Amr or Moussa

- Kelif el Boroud

- Prehistory of Central North Africa

References

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000-04-30). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 93. ISBN 9780306461583.

- "Macmillan Dictionary of Archaeology - Google Książki".

- 2005 D. Lubell. Continuité et changement dans l'Epipaléolithique du Maghreb. In, M. Sahnouni (ed.) Le Paléolithique en Afrique: l’histoire la plus longue, pp. 205-226. Paris: Guides de la Préhistoire Mondiale, Éditions Artcom’/Errance.

- 2004 N. Rahmani. Technological and cultural change among the last Hunter-Gatherers of the Maghreb: the Capsian (10,000 B.P. to 6000 B.P.). Journal of World Prehistory 18(1): 57-105.

- 2013 S. Mulazzani (ed.) Le Capsien de Hergla (Tunisie). Culture, Environnement et économie. Reports in African Archaeology 4. Frankfurt a. M., Africa Magna Verlag. ISBN 978-3-937248-36-3.

- 1984 D. Lubell. Paleoenvironments and Epi Paleolithic economies in the Maghreb (ca. 20,000 to 5000 B.C.). In, J.D. Clark & S.A. Brandt (eds.), From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 41-56.

- 1984 D. Lubell, P. Sheppard & M. Jackes. Continuity in the Epipalaeolithic of northern Africa with an emphasis on the Maghreb. In, F. Wendorf & A. Close (eds.), Advances in World Archaeology, Vol. 3: 143-191. New York: Academic Press.

- 2004 D. Lubell.Prehistoric edible land snails in the circum-Mediterranean: the archaeological evidence. In, J-J. Brugal & J. Desse (eds.), Petits Animaux et Sociétés Humaines. Du Complément Alimentaire Aux Ressources Utilitaires. XXIVe rencontres internationales d’archéologie et d’histoire d’Antibes, pp. 77-98. Antibes: Éditions APDCA.

- 1979 C. Roubet. Économie Pastorale Préagricole en Algérie Orientale: le Néolithique de Tradition Capsienne. Paris: CNRS.

- 1985 D. Ferembach. On the origin of the Iberomaurusians (Upper Paleolithic, North Africa): a new hypothesis. Journal of Human Evolution 14: 393-397.

- 1991 P. Sheppard & D. Lubell. Early Holocene Maghreb prehistory: an evolutionary approach. Sahara 3: 63-9

- D. Lubell (October 1, 2001). "Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene Maghreb". In Peregrine, Peter Neal; Ember, Melvin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Prehistory (PDF). 1 : Africa. New York: Springer. pp. 129–149.

- Language, Volume 61, Issues 3-4. Linguistic Society of America. 1985. p. 695. Retrieved 31 January 2017.