Capital punishment in California

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in the U.S. state of California. As of March 2019, further executions are halted by an official moratorium ordered by Governor Gavin Newsom.[1]

The state carried out 709 executions from 1778 to the 1972 California Supreme Court decision in People v. Anderson that struck down the state capital punishment statute.[2][3] California voters reinstated the death penalty a few months later, with Proposition 17 legalizing the death penalty in the state constitution and ending the Anderson ruling. Since that ruling, there have been just 13 executions, yet hundreds of inmates have been sentenced. The last execution that took place in California was in 2006.

As of August 2018, official California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) records show 744 inmates on California's death row.[4] Reports published in August 2017, when there were 746 on death row, showed that 22 of those were waiting on women’s death row in the Central California Women's Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla.[5][6]

California rejected two initiatives to repeal the death penalty by popular vote in 2012 and 2016, and it adopted in 2016 another proposal to expedite its appeal process.[7]

History

The first known death sentence in California was recorded in 1778. On April 6, 1778 four Kumeyaay chiefs from a Mission San Diego area ranchería were convicted of conspiring to kill Christians and were sentenced to death by José Francisco Ortega, Commandant of the Presidio of San Diego; the four were to be shot on April 11.[2] However, there is some doubt whether the executions actually took place.[3]

Four methods have been used historically for executions. Until slightly before California was admitted into the Union, executions were carried out by firing squad. Upon admission, the state adopted hanging as the method of choice.[8]

The penal code was modified on February 14, 1872, to state that hangings were to take place inside the confines of the county jail or other private places. The only people allowed to be present were the county sheriff, a physician, and the county District Attorney, who would in addition select at least 12 "reputable citizens". No more than two "ministers of the gospel" and no more than five people selected by the condemned could also be present.[8]

Executions were moved to the state level in 1889 when the law was updated so that hangings would occur in one of the state prisons—San Quentin State Prison and Folsom State Prison. According to the California Department of Corrections, although the law did not require the trial judge to choose a specific prison, it was customary for recidivists to be sent to Folsom. Under these new laws, the first execution at San Quentin was Jose Gabriel on March 3, 1893, for murder. The first hanging at Folsom was Chin Hane, also for murder, on December 13, 1895. A total of 215 inmates were hanged at San Quentin and a total of 92 were hanged at Folsom.[8]

In previous eras the California Institution for Women housed the death row for women.[9]

1972 suspension of capital punishment

On April 24, 1972, the Supreme Court of California ruled in People v. Anderson that the state's current death penalty laws were unconstitutional. Justice Marshall F. McComb was the lone dissenter, arguing that the death penalty deterred crime, noting numerous Supreme Court precedents upholding the death penalty's constitutionality, and stating that the legislative and initiative processes were the only appropriate avenues to determine whether the death penalty should be allowed.[10] The majority's decision spared the lives of 105 death row inmates, including Sirhan Sirhan (assassin of Robert F. Kennedy) and serial killer Charles Manson.[11] McComb was so outraged by the decision that he walked out of the courtroom during its reading.[12]

Following the ruling, the Constitution of California was modified to reinstate capital punishment under an initiative called Proposition 17. In 1973 a new statute was subsequently enacted, making the death penalty mandatory for a number of crimes including first degree murder in specific instances, kidnapping during which a victim dies, train wrecking during which a victim dies, treason against the state, and assault by a life prisoner if the victim dies within a year.[8]

The debate over capital punishment played out in a somewhat similar fashion on the national level. On June 29, 1972, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Furman v. Georgia, holding all capital punishment statutes then in effect in the United States to be unconstitutional. On July 2, 1976, the Supreme Court, in Gregg v. Georgia, reviewing capital punishment laws enacted in response to its Furman decision, found constitutional those statutes that allowed a jury to impose the death penalty after consideration of both aggravating and mitigating circumstances. On the same date, the Court held that statutes imposing a mandatory death penalty were unconstitutional.[13]

In a later decision in 1976, the Supreme Court of California again held the state's death penalty statute was unconstitutional as it did not allow the defendant to enter mitigating evidence. A further 70 prisoners had their sentences commuted following this. The next year, the statute was updated to deal with these issues. Life imprisonment without possibility of parole was also added as a punishment for capital offenses. A later change to the statute was in 1978 after Proposition 7 passed. This gave an automatic appeal to the Supreme Court of California, which would directly affirm or reverse the sentence and conviction without going through an intermediate appeal to the California Courts of Appeal.

In 1983, The State Bar of California created The California Appellate Project as a legal resource center to implement the constitutional right to counsel for indigent persons facing execution.[14] At around the time of its founding, Michael Millman became the director of CAP. Millman served as director of CAP for 30 years.[15] CAP oversees the efforts to assist private lawyers representing the more than 700 people on California’s death row.[15]

1986 retention elections

On November 4, 1986, three members of the state supreme court were ousted from office by voters after a high-profile campaign that cited their categorical opposition to the death penalty.[16]

This included chief justice Rose Bird, who was removed by a margin of 67 to 33 percent. She reviewed a total of 64 capital cases appealed to the court, in each instance issuing a decision overturning the death penalty that had been imposed at trial. She was joined in her decision to overturn by at least three other members of the court in 61 of those cases.[17] This led Bird's critics to claim that she was substituting her own opinions and ideas for the laws and precedents upon which judicial decisions are supposed to be made.[18]

Resumption of executions and introduction of lethal injection

In April 21, 1992 the state carried out its first execution since 1967 by putting to death Robert Alton Harris for the murders of two teenage boys in San Diego. A series of four stays of execution issued by the Ninth Circuit appeal court delayed the execution, causing the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene to vacate the stays and prohibit all other federal courts from any further intervention, ruling that the lower court decisions caused "abusive delays" and were "attempts to manipulate the judicial process".[19]

The available methods were expanded to two in January 1993, with lethal gas as the standard but with lethal injection offered as a choice for the inmate.[8] David Mason, the first inmate to have this choice, made no selection, so was executed by the lethal gas default in August 1993. Following a legal challenge and Ninth Circuit appeal court decision in 1996, lethal gas was suspended, with lethal injection becoming the only method.[8][20] Serial killer William Bonin was the first person to be executed under these new laws, on February 23, 1996. Thirteen people have been executed in California since the death penalty was reinstated in 1977, though 143 other people have died on death row from other causes (28 of them from suicide) as of August 9, 2020.[21]

Lethal injection litigation

During the term of Arnold Schwarzenegger as governor, the state carried out two prominent executions in less than five weeks, with Stanley Tookie Williams in December 2005 and Clarence Ray Allen in January 2006.

A month later, in February 2006, U.S. District Court Judge Jeremy D. Fogel blocked the execution of convicted murderer Michael Morales because of a lawsuit against the lethal injection protocol.[22] It was argued that if the three-drug lethal injection procedure were administered incorrectly, it could lead to suffering for the condemned, potentially constituting cruel and unusual punishment. The issue arose from an injunction made by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals which held that an execution could only be carried out by a medical technician legally authorized to administer intravenous medications. The case led to a de facto moratorium of capital punishment in California as the state was unable to obtain the services of a licensed medical professional to carry out the execution.[23]

When the state planned the execution of Albert Greenwood Brown in late 2010, judge Fogel declined to stay it, citing all the efforts the state made to comply with his earlier ruling. But the 9th circuit appeal court disagreed with him and vacated the judgment, further delaying executions in the state.[24]

Studies

The state supreme court proposed in 2007 that the state adopt a constitutional amendment allowing the assignment of capital appeals to the courts of appeal to alleviate the backlog of such cases.[25]

Several victims' families testified to the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice in opposition to capital punishment, explaining that whilst they had suffered great losses, they did not view retribution as morally acceptable, and that the high cost of capital punishment was preventing the solving of cold cases.[26]

But others who contest this argument said the greater cost of trials where the prosecution does seek the death penalty is offset by the savings from avoiding trial altogether in cases where the defendant pleads guilty to avoid the death penalty.[27]

The California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice[28] in 2008 concluded after an extensive review that under the current death penalty system, death sentences are unlikely ever to be carried out (with extremely rare exceptions) because of a process “plagued with excessive delay” in the appointment of post-conviction counsel and a “severe backlog” in the California Supreme Court's review of death judgments. According to CCFAJ's report, the lapse of time from sentence of death to execution constitutes the longest delay of any death penalty state, and the Commission urged reform to expedite the appeal process.

Another study released in 2011 found that since 1978 capital punishment has cost California about $4 billion. A 2011 article by Arthur Alarcon, long-time judge of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal, and law professor Paula Mitchell, concluded that "since reinstating the death penalty in 1978, California taxpayers have spent roughly $4 billion to fund a dysfunctional death penalty system that has carried out no more than 13 executions."[29]

Proposition 34, the SAFE California Act

A coalition of death penalty opponents including law enforcement officials, murder victims' family members, and wrongly convicted people launched an initiative campaign for the "Savings, Accountability, and Full Enforcement for California Act," or SAFE California, in the 2011-2012 election cycle.[30] The measure, which became Proposition 34, would replace the death penalty with life imprisonment without the possibility of parole, require people sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole to work in order to pay restitution to victims' families, and allocate approximately $30 million per year for three years to police departments for the purpose of solving open murder and rape cases.[31] Supporters of the measure raised $6.5 million, dwarfing the $1 million raised by opponents of Proposition 34.[32]

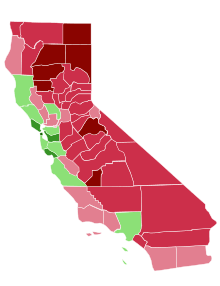

The proposition was defeated with 52% against and 48% in favor.[33]

July 2014 and November 2015 federal decisions

On July 16, 2014, federal judge Cormac J. Carney of the United States District Court ruled that California's death penalty system is unconstitutional because it is arbitrary and plagued with delay. The state has not executed a prisoner since 2006. The judge stated that the current system violates the Eighth Amendment's ban on cruel and unusual punishment by imposing a sentence that “no rational jury or legislature could ever impose: life in prison, with the remote possibility of death.”

However, on November 12, 2015, a panel of the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the district court's ruling in a 3-0 published decision. The three judges held that the claim was not justiciable under federal habeas corpus.[34][35]

2015 state lawsuit

In February 2015, Sacramento County Superior Court Judge Shelleyanne Chang ruled that state law compelled the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to develop a way to execute inmates by lethal injection.[36] Later that year a new protocol providing a single-drug execution method was developed to comply with the ruling.[37]

This was the result of a lawsuit brought by family members of murder victims. Supporters of capital punishment blamed the nearly three-year wait for a new protocol on "lack of political will"[36] and attempt to render the death penalty "impractical and then argue for repeal on the grounds of practicality".[37]

Propositions 62 and 66

On November 8, 2016, California voted on two competing initiatives about capital punishment. Proposition 62 which, as Proposition 34, would have abolished the death penalty, was rejected by a 53-47 margin. The other initiative, Proposition 66, provides the streamlining of the capital appeal process, and also requires death-row offenders to work in jail and pay restitution to victims families, something they were previously exempted from. The measure passed 51-49.[7] Its constitutionality was upheld 5-2 by the state supreme court on August 24, 2017, though the court held that one provision requiring it to decide direct appeals of capital cases within five years was directive rather than mandatory. The court ordered that Prop 66 take effect after this decision becomes final.[38]

Current legislation

Legal process

When the prosecution seeks the death penalty, the sentence is decided by the jury and must be unanimous.

In case of a hung jury during the penalty phase of the trial, a retrial happens before another jury. If the second or any subsequent jury is also deadlocked, the judge has discretion to order another retrial or impose a life sentence.[39]

Under the state Constitution, the power of clemency belongs to the Governor of California. But if the offender was twice convicted of a felony, the governor can grant a commutation only on recommendation of the Supreme Court, with at least four judges concurring.[40]

Executions are carried out by lethal injection, but an inmate sentenced before its adoption may elect to be executed by gas inhalation instead. If one of these two methods is held invalid, the state is required to use the other method.[41]

Capital offenses

The penal code provides for possible capital punishment in:

- treason against the state of California, defined as levying war against the state, adhering to its enemies, or giving them aid and comfort[42]

- first-degree murder with special circumstances[43]

- for financial gain (1)

- the defendant had previously been convicted of first or second degree murder (2)

- multiple murders (3)

- committed using explosives (4) ; (6)

- to avoid arrest or aiding in escaping custody (5)

- the victim was an on-duty peace officer; federal law enforcement officer or agent; or firefighter (7) ; (8) ; (9)

- the victim was a witness to a crime and the murder was committed to prevent them from testifying (10)

- the victim was a prosecutor or assistant prosecutor; judge or former judge; elected or appointed official; juror; and the murder was in retaliation for the victim's official duties (11) ; (12) ; (13) ; (20)

- the murder was "especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel, manifesting exceptional depravity" (14)

- the murderer lay in wait for the victim (15)

- the victim was intentionally killed because of their race, religion, nationality, or sexual orientation. (a hate crime) (16)

- the murder was committed during the committing of a robbery; kidnapping; rape; sodomy; performance of a lewd or lascivious act upon the person of a child under the age of 14 years; oral copulation; burglary; arson; train wrecking; mayhem; rape by instrument; carjacking; torture; poisoning (17)

- the murder was intentional and involved the infliction of torture (18)

- poisoning (19)

- the murder was committed by discharging a firearm from a motor vehicle (21)

- the defendant is an active member of a criminal street gang and was to further the activities of the gang (22)

- train wrecking which leads to a person's death[44]

- perjury or subornation of perjury causing execution of an innocent person[45]

- fatal assault by an escaped capital convict serving a life sentence.

In 2008, the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice criticized the high number of aggravating factors as giving to local prosecutors too much discretion in picking cases where they believe capital punishment is warranted. The Commission proposed to reduce them to only five (multiple murders, torture murder, murder of a police officer, murder committed in jail, and murder related to another felony).[46] Columnist Charles Lane went further, and proposed that murder related to a felony other than rape should no longer be a capital crime when there is only one victim killed.[47]

Death row and execution chamber

Men condemned to death in California must (with some exceptions) be held at San Quentin State Prison, while condemned women are held at Central California Women's Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla. San Quentin also houses the state execution chamber.[48] Women executed in California would be transported to San Quentin by bus before being put to death.[49]

As of 2015, 708 male death row inmates were held at San Quentin. There were 23 male California death row inmates in medical facilities, other state prisons, and in correctional facilities in proximity to their court hearings. As of August 2017, there were 22 female death row inmates at CCWF.[5][50]

Public opinion

The Field Research Corporation found in February 2004 that when asked how they personally felt about capital punishment, 68% supported it and 31% opposed it (6% offered no opinion). This was a decrease from 72% support two years previous, and an increase from 63% in 2000. This poll was asked about the time that Kevin Cooper had his execution stayed hours before his scheduled death after 20 years on Death Row. When asked if they thought the death penalty was generally fair and free of error in California, 58% agreed and 32% disagreed (11% offered no opinion). When the results were broken down along ethnicity, of the people who identified themselves as African American, 57% disagreed that the death penalty was fair and free of error.

A poll in March 2012 found that "61% of registered voters from the state of California say they would vote to keep the death penalty, should a death penalty initiative appear on the November 2012 ballot"[51] An August 2012 poll found that "support for Prop 34, which would repeal California's death penalty, fell from 45.5% to 35.9%."[52]

A PPIC poll from September 2012 showed that 55% of all adults and 50% of likely voters prefer life in prison without the possibility of parole over the death penalty when given the choice.[53]

A Field Poll in September 2014 showed that 56% support the death penalty, down from 69% three years earlier. Support for the death penalty in California had not been at this low a level since the mid-1960s.[54]

See also

References

- "California governor to halt executions". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- Ruscin, p. 196; Bancroft, vol. i., p. 316

- Engelhardt 1920, pp. 96–97: Reference is made to three letters written by Father Serra to Father Lasuén dated April 22 and June 10, 1778 and September 28, 1779 wherein Father Serra expresses his satisfaction over Governor Felipe de Neve's apparent grants of clemency in this regard. Based on these writings, Engelhardt concludes "It would seem that the sentence of death was commuted. At any rate, there are no particulars as to an execution."

- "Condemned Inmate List". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- These are the 746 inmates awaiting execution on California's death row, Los Angeles Times, Paige St. John & Maloy Moore, August 24, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- "Facts About The Death Penalty" (PDF). Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "California votes to keep death penalty". sacbee.com. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- "The History of Capital Punishment in California". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- "Court Ruling Won't Mean Bloodbath On Death Row." Associated Press at the Tuscaloosa News. Tuesday February 15, 1972. p. 10. Retrieved on Google News (6/15) on March 27, 2013. "There are five women under a sentence of death. Three of Manson's convicted accomplices, Susan Atkins, Leslie Houten, and Patricia Krenwinkel, are in a special women's section of the row built at the California Institute for Women at Frontera."

- People v. Anderson, 6 Cal. 3d 628 (Cal. 1972).

- Associated Press (February 18, 1972). "California Court Bars Death Penalty". Milwaukee Journal.

- United Press International (February 18, 1972). "Dissenter Is Upset, Walks Out of Court". Modesto Bee.

- Ross, Lee; Ellsworth, Pheobe (January 1983). "Public opinion and capital punishment: a close examination of the views of abolitionists and retentionists". 29 (1): 116–169. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "About CAPSF". capsf.org. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- "Supreme Court Marks Passing of Michael Millman". courts.ca.gov. California Supreme Court. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Lindsey, Robert. "Deukmejian and Cranston Win As 3 Judges Are Ousted." The New York Times, 6 November 1986, sec. A, p. 30.

- Purdum, Todd S. (December 6, 1999). "Rose Bird, Once California's Chief Justice, Is Dead at 63". The New York Times. sec. B, p. 18. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Rose Bird Deserved To Be Removed". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Harris executed at San Quentin (The Union Democrat)". google.com. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- Fierro, Ruiz, Harris v. Gomez, 94-16775 (U.S. 9th Circuit 1996).

- "Condemned Inmates Who Have Died Since 1978". Cdcr.ca.gov. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Williams, Carol J. (September 22, 2010). "Clock is ticking on first execution at San Quentin's revamped death chamber". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kleinfeld, A.; KcKeown, M.; Fisher, R. (September 27, 2010). "Michael Angelo Morales and Albert Greenwood Brown v. Matthew Cate" (PDF). U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- Weinstein, Henry (November 20, 2007). "Court urges amendment to speed death penalty reviews". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Herron, Aundré M. (April 20, 2008). "The death penalty is not civilized". Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Study: cost savings from repeal of death penalty may be elusive". Cjlf.org. February 25, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Alarcon law review" (PDF). Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elias, Paul. Calif. voters retain death penalty despite costs, November 7, 2012. Associated Press.

- "Proposition 34: Death Penalty - California State Government". Smartvoter.org. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "Challenge to Calif. Death Penalty Scheme Fails". Bna.com. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- "Federal Appeals Court Reverses Ruling That Ended California's Death Penalty". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- "Judge says families can push state to devise execution protocol". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- "California death penalty: New execution method under scrutiny". Mercury News. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- "Supreme Court Case: S238309". appellatecases.courtinfo.ca.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- "CHAPTER 1 - Homicide - Section 190.4". law.justia.com. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "CALIFORNIA CONSTITUTION - ARTICLE 5 EXECUTIVE – SEC. 8". law.justia.com. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "CHAPTER 1 - Executing Death Penalty - Section 3604". law.justia.com. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- "California Penal Code § 37". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- "Chapter 1 of Title 8 of Part 1 of the California Penal Code". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- "Chapter 5 of Title 8 of Part 1 of the California Penal Code". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- "California Penal Code § 128". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- "Official recommendations on the fair administration of the death penalty in california". ccfaj.org. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- Charles Lane (2010), Stay of Execution: Saving the Death Penalty from Itself, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, p.110-111

- "Penal Code section 3600-3607". Leginfo.ca.gov. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

The judgment of death shall be executed within the walls of the California State Prison at San Quentin." and "Upon the affirmance of her appeal, the female person sentenced to death shall thereafter be delivered to the warden of the California state prison designated by the department for the execution of the death penalty,[...]

- Corwin, Miles. "Death's Door : State's Only Condemned Woman Awaits Her Fate." Los Angeles Times. April 19, 1992. Retrieved on March 22, 2016.

- St. John, Paige. "California's death row, with no executions in sight, runs out of room ." Los Angeles Times. March 30, 2015. Retrieved on March 22, 2016.

- "Results of SurveyUSA News Poll #19044". Surveyusa.com. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "News Categories | Pepperdine Newsroom". Publicpolicy.pepperdine.edu. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- "PPIC Statewide Survey : Californians & their government" (PDF). Ppic.org. September 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- Chokshi, Niraj. "Support for the death penalty in California hits a five-decade low". Washington Times. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

External links

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Executions in California 1778–1967

- "Two-thirds of California voters favor the death penalty, But a sizeable minority believe it has not been fairly implemented (PDF)" (PDF). Field Research Corporation. March 5, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 14, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2005.