Stylidium

Stylidium (also known as triggerplants or trigger plants) is a genus of dicotyledonous plants that belong to the family Stylidiaceae. The genus name Stylidium is derived from the Greek στύλος or stylos (column or pillar), which refers to the distinctive reproductive structure that its flowers possess.[1] Pollination is achieved through the use of the sensitive "trigger", which comprises the male and female reproductive organs fused into a floral column that snaps forward quickly in response to touch, harmlessly covering the insect in pollen. Most of the approximately 300 species are only found in Australia, making it the fifth largest genus in that country. Triggerplants are considered to be protocarnivorous or carnivorous because the glandular trichomes that cover the scape and flower can trap, kill, and digest small insects with protease enzymes produced by the plant. Recent research has raised questions as to the status of protocarnivory within Stylidium.[2]

| Stylidium | |

|---|---|

| |

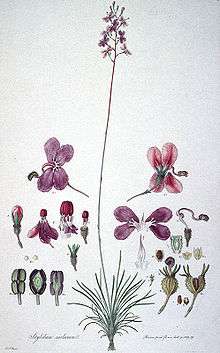

| Flower of Stylidium graminifolium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Stylidiaceae |

| Subfamily: | Stylidioideae |

| Genus: | Stylidium Sw. |

| Species | |

|

See separate list. | |

Characteristics

The majority of the Stylidium species are perennial herbs of which some are geophytes that utilize bulbs as their storage organ. The remaining small group of species consists of ephemeral annuals.[3]

Members of the genus are most easily identified by their unique floral column, in which the stamen and style are fused. The column—also commonly called a "trigger" in this genus—typically resides beneath the plane of the flower. Stylidium flowers are zygomorphic, which means they are only symmetrical in one plane.[4] Flowers usually bloom in the late spring in Australia.[5]

Morphology

Species of the genus Stylidium represent a very diverse selection of plants. Some are only a few centimeters tall, while others can grow to be 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) tall (S. laricifolium). One typical plant form is a dense rosette of leaves close to the ground that gives rise to the floral spike in the center. Plant forms range from wiry, creeping mats (S. scandens) to the bushy S. laricifolium.[5][6]

Flower morphology differs in details, but ascribes to a simple blueprint: four petals, zygomorphic in nature, with the trigger protruding from the "throat" of the flower and resting below the plane of the flower petals. Flower size ranges from many species that have small 0.5 cm (0.20 in) wide flowers to the 2–3 cm (1–1 in) wide flowers of S. schoenoides. Flower color can also vary from species to species, but most include some combination of white, cream, yellow, or pink. Flowers are usually arranged in a spike or dense raceme, but there is at least one exception to the rule: S. uniflorum, as its name suggests, produces a single flower per inflorescence.[6]

Leaf morphology is also very diverse in this large genus. Some leaves are very thin, almost needle-like (S. affine), while others are short, stubby, and arranged in rosettes (S. pulviniforme). Another group of species, such as S. scandens (climbing triggerplant) form scrambling, tangled mats typically propped up on aerial roots.[6]

Pollination mechanism

The column typical of the genus Stylidium is sensitive and responds to touch. The change in pressure when a pollinating insect lands on a Stylidium flower causes a physiological change in the column turgor pressure by way of an action potential, sending the column quickly flying toward the insect.[7] Upon impact, the insect will be covered in pollen and stunned, but not harmed. Because the column comprises the fused male and female reproductive organs of the flower, the stamen and stigma take turns in dominating the function of the column—the anthers develop first and then are pushed aside by the developing stigma. This delayed development of the stigma prevents self-pollination and ensures that cross pollination will occur between individuals of a population. Different species have evolved the trigger mechanism in different locations, with some attacking the pollinating insect from above and others from below (a "punch in the gut" to the insect).[5][8]

The response to touch is very quick in Stylidium species. The column can complete its "attack" on the insect in as little as 15 milliseconds. After firing, the column resets to its original position in anywhere from a few minutes to a half hour, depending on temperature and species-specific qualities. The column is able to fire many times before it no longer responds to stimuli. The response time is highly dependent upon ambient temperature, with lower temperatures relating to slower movement.[9] Stylidium species are typically pollinated by small solitary bees and the nectar-feeding bee flies (Bombyliidae).[10]

Carnivory

Stylidium species with glandular trichomes on their sepals, leaves, flower parts, or scapes have been suggested to be protocarnivorous (or paracarnivorous). The tip of the trichome produces a sticky mucilage—a mixture of sugar polymers and water—that is capable of attracting and suffocating small insects.[6] The ability to trap insects may be a defensive mechanism against damage to flower parts. However, trichomes of S. fimbriatum have been shown to produce digestive enzymes, specifically proteases, like other carnivorous plants. Adding species of Stylidium to the list of plants that engage in carnivory would significantly increase the total number of known carnivorous plants.[11]

The insects captured by the glandular trichomes are too small to serve any role in pollination. It is unclear, however, whether these plants evolved the ability to trap and kill insects as an adaptation to low environmental nutrient availability or simply a defensive mechanism against insects damaging flower parts.[6]

There is also a correlation between location of Stylidium species and proximity of known carnivorous species, like sundews (Drosera), bladderworts (Utricularia), the Albany pitcher plant (Cephalotus follicularis), and the rainbow plant (Byblis). While this alone does not prove that Stylidium species are themselves carnivorous, the hypothesis is that the association arose because Stylidium species and the known carnivorous plants obtain scarce nutrients using the same source, namely captured insects. Preliminary proof is given that the trapping mechanisms of two associated plants are the same (the tentacles of Byblis and Drosera), though this may be only a coincidence and further research must be done.[6] Recent research has raised questions as to the status of protocarnivory within Stylidium.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Most Stylidium species are endemic to Australia. In Western Australia alone, there are more than 150 species, at least 50 of which are in the area immediately around Perth. There are at least four species of Stylidium that are not confined to the Australian continent: S. tenellum is found in Myanmar, Melaka, and Tonkin; S. kunthii in Bengal and Myanmar; S. uliginosum in Queensland, Sri Lanka, and the south coast of China; and S. alsinoides in Queensland and the Philippines. The cladistic group Stylidium contains more than 230 individual species (more than 300 species exist, but many specimens have not yet been formally described),[12] making it the fifth largest genus in Australia.[3]

Stylidium habitat includes grassy plains, open heaths, rocky slopes, sandplains, forests, and the margins of creeks and water holes.[5] Somes species, such as S. eglandulosum, can even be found in disturbed areas like near roads and under powerlines. Others (i.e. S. coroniforme) are sensitive to disturbance and are considered rare because of their extremely specific habitat.[6]

Even though many species of Stylidium may coexist in the same location, natural hybrids between species have not often been reported. Both natural hybridisation in the field and artificial hybridisation in cultivation are rare.[10] The first natural hybrid, S. petiolare × S. pulchellum, was reported by Sherwin Carlquist in 1969 between Capel and Boyanup in Western Australia.[13]

Botanical history

Discovery and description of new Stylidium species has been occurring since the late 18th century, the first of which was discovered in Botany Bay in 1770 by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander during their travels in the Pacific with James Cook aboard the Endeavour.[12] Seven species were collected by Banks and Solander, some of which were sketched by Sydney Parkinson on board the Endeavour and were later engraved in preparation for publication in Banks' Florilegium. Later, in the early 19th century, the French botanist Charles François Antoine Morren wrote one of the first descriptions of the triggerplant anatomy, illustrated by many botanical artists including Ferdinand Bauer. Around the same time, British botanist Robert Brown described (or "authored") several Stylidium species, including S. adnatum and S. repens. More species began to be described as more botanists explored Australia more thoroughly.

In 1958, Rica Erickson wrote Triggerplants, describing habitat, distribution, and plant forms (ephemeral, creeping, leafy-stemmed, rosette, tufted, scale-leaved, and tropical). It was Erickson that began placing certain species into these morphologically-based groups, which may or may not resemble true taxonomic divergences. It was not until the 1970s and 1980s that research of the trigger physiology was begun in the lab of Dr. Findlay of Flinders University. Douglas Darnowski added to the growing library of knowledge on Stylidium when he published his book Triggerplants in 2002, describing an overview of habitat, plant morphology, carnivory, and research done to date. Following its publication, he co-founded the International Triggerplant Society.[14]

As of 2002, only 221 Stylidium species were known.[15] There are now over 300 species, many of which are awaiting formal description.

Cultivation

Most Stylidium species tend to be hardy species and can be easily cultivated in greenhouses or gardens. They are drought resistant, hardy to cold weather, and the species diversity in this genus gives gardeners a wide variety of choices. Most species that are native to Western Australia will be cold hardy to at least -1 to -2 °C. The few that can be found all over Australia, like S. graminifolium, will tolerate a wider range of habitat since their native ranges includes a great diversity of ecoregions. Some species of triggerplants are suitable for cultivation outdoors outside of the Australian continent including most of the United Kingdom and as far north as New York City or Seattle in the United States.[6]

Cultivation from seed may be difficult or easy, depending on the species. The more difficult species to grow include the ones that require a period of dormancy or smoke treatment to simulate a bushfire. Stylidium specimens should be grown in a medium that is kept moist and has a relatively low concentration of nutrients. They appear to be sensitive to disturbance of their root systems. Minimization of such disturbance will likely result in healthier plants.[6]

References

- Curtis's Botanical Magazine. (1832). Stylidium scandens, Volume 59: Plate 3136.

- Nge, Francis J.; Lambers, Hans (2018). "Reassessing protocarnivory ? how hungry are triggerplants?". Australian Journal of Botany. 66 (4): 325. doi:10.1071/BT18059. ISSN 0067-1924.

- Good, R. (1925). On the Geographical Distribution of the Stylidiaceae. New Phytologist, 24(4): 225-240.

- Laurent, N., Bremer, B., Bremer, K. (1998). Phylogeny and Generic Interrelationships of the Stylidiaceae (Asterales), with a Possible Extreme Case of Floral Paedomorphosis. Systematic Botany, 23(3): 289-304.

- Erickson, Rica. (1961). An introduction to triggerplants. Australian Plants, 1(9): 15-17. (Available online: HTML)

- Darnowski, Douglas W. (2002). Triggerplants. Australia: Rosenberg Publishing. ISBN 1-877058-03-3

- Findlay, G.P. and Pallaghy, C.K. (1978). Potassium chloride in the motor tissue of Stylidium. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 5(2): 219 - 229. (Abstract available online: HTML)

- Armbruster, W.S., Edwards, M.E., Debevec, E.M. (1994). Floral Character Displacement Generates Assemblage Structure of Western Australian Triggerplants (Stylidium). Ecology, 75(2): 315-329.

- Findlay, G.P. (1978) Movement of the Column of Stylidium crassifolium as a Function of Temperature. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 5(4): 477-484.

- Armbruster, W. S., and N. Muchhala. 2009. Associations between floral specialization and species diversity: cause, effect, or correlation? Evolutionary Ecology, 23: 159-179.

- Darnowski, D.W., Carroll, D.M., Płachno, B., Kabanoff, E., and Cinnamon, E. (2006). Evidence of protocarnivory in triggerplants (Stylidium spp.; Stylidiaceae). Plant Biology, 8(6): 805-812. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924472

- Information from an October 26, 2004 edition of "Talking Plants" Archived September 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, a program of the Botanic Gardens Trust, a division of the New South Wales Department of Environment and Conservation

- Carlquist, S.J. (1969). Studies in Stylidiaceae: New taxa, field observations, evolutionary tendencies. Aliso, 7: 13-64.

- Darnowski, Douglas W. (2002). The history of triggerplants. International Triggerplant Society. (Archived, available online: HTML)

- Wagstaff, S.J. and Wege, J. (2002). Patterns of diversification in New Zealand Stylidiaceae. American Journal of Botany, 89(5): 865-874. (Available online: HTML or PDF versions)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

![]()

- Australian Department of the Environment and Heritage document on the "Wongan Hills Triggerplant (Stylidium coroniforme) Interim Recovery Plan 2003-2008". (PDF version)

- FloraBase (Western Australia's flora database) entry on Stylidium.

- Association of Societies for Growing Australian Plants (ASGAP) information on Stylidium laricifolium and Stylidium graminifolium.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) list of published Stylidium species names.

- Photos and animations of triggerplants, featuring several species.

- The International Triggerplant Society.