Campine

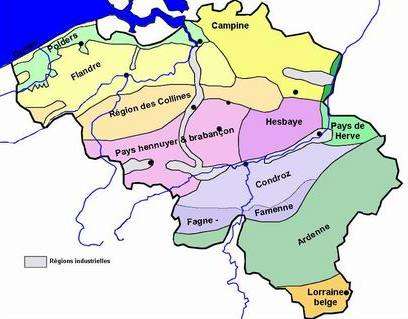

The Campine (French) or De Kempen (Dutch) is a natural region situated chiefly in north-eastern Belgium and parts of the south-eastern Netherlands which once consisted mainly of extensive moors, tracts of sandy heath, and wetlands. It encompasses a large northern and eastern portion of Antwerp province and adjacent parts of Limburg in Belgium, as well as portions of the Dutch province of North Brabant (area southwest of Eindhoven) and Dutch Limburg around Weert.

Today the Campine is becoming a popular touristic destination. Old farms have been transformed into bed-and-breakfast hotels, the restaurant and café business is very active, and an extensive cycle touring network has come into existence over the past few years.

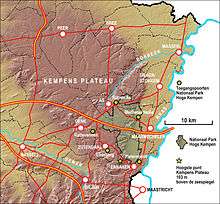

Part of the Campine is protected as the Hoge Kempen Nationaal Park (High Campine National Park). It is located in the east of the Belgian province of Limburg, between Genk and the Meuse valley and was opened in March 2006.[1] Covering almost 60 square kilometres (23 sq mi), it forms part of the Natura 2000 network.[2] The area is mostly heathland and pine forest. In May 2011 it was placed on UNESCO's Tentative List for consideration as a World Heritage Site.

Etymology

The Medieval Latin name Campania, firstly attested in the mid-11th century by a monk of Saint-Trond named Stepelinus, stems from the root kamp- ('field') attached to the suffix -injo, denoting the uncultivated or the virgin fields.[3]

The inhabitants of the Campine region are known as Kempenaars.

Culture

The region, described as a desolate flat land often appears in the books of the prominent Flemish writer Hendrik Conscience (1812–1883), who spent much of his childhood there. Another author who has written many novels playing in the Campine was Georges Eekhoud (1854–1927). In 1837 Victor Hugo made a journey through Belgium and visited the Campine and the towns of Lier and Turnhout, and wrote about his journey.[4] During the interbellum Felix Timmermans, Stijn Streuvels, Jozef Simons and the poet Jozef De Voght wrote about the Belgian Campine. The painters Jakob Smits (1855–1928) and Frans Van Giel (1892–1975) painted many Campine landscapes.

The region is rich in folk tales, such as the stories about the Buckriders (Dutch: Bokkenrijders) and those concerning the gnome king Kyrië (Dutch: Kabouterkoning Kyrië).

The Museum Kempenland in Eindhoven has a considerable and historically important art collection of painters, draughtsmen, sculptors, blacksmiths and other craftsmen from this region. Much of the architectural, agrarian and historical and cultural heritage of the Campine can be visited in the open-air museum of Bokrijk. The old way of living and the Campine dialects have been the topic of scientific research.[5] In the Roman era the name of the region was Toxandria or Taxandria.

History

The Campine is an area in the Belgian provinces Antwerp, Limburg and the extreme north of the province Flemish Brabant, and in the south of the Dutch province Noord-Brabant. It stretches from the east of the city of Antwerp and towards the west of Eindhoven. Farther east the Campine is in the Groote Peel, a region which is geographically related to the Campine. The south border is formed by the river Demer, and the east border by the valley of the river Meuse. The Campine plateau is part of the Campine region. The Campine Basin, which extends from Belgium into the Netherlands, is formed by the Devonian and Carboniferous sedimentary rocks on the northern flank of the Brabant Massif.

Since it was a region with a poor sandy soil, there are only a few old or large cities in the region. Most of those cities are located at the outer rim of the region, such as Hasselt, Diest, Aarschot, Lier (the self-styled gate of the Campine, a title also claimed by the Northern-Brabant Oirschot), Breda, Tilburg, Eindhoven, Maaseik, and Maastricht. Turnhout is an exception. West of Turnhout clay was used for the production of barge, which is one of the reasons why the Noord-Kempens Canal was dug to Antwerp. Also the more central Herentals was an historical industrial center, thanks to its textile industry of which the Lakenhal on the main market place is a remaining monument. The printing industry in Turnhout is historically important, with companies such as Brepols and more recently Cartamundi.

The region was sparsely populated, and therefore chosen by monks who were looking for silence, such as those of the abbeys of Achel, Brecht, Zundert, Postel, Westmalle and Tongerlo. In the 19th and 20th centuries, industry established itself in the region, such as the metallurgy in Balen-Overpelt-Lommel. In 1872 the Sablières et Carrières Réunies (SCR), now Sibelco, was founded to extract the silica sand layers in Mol for industrial applications (glass). In 1891, the Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. was founded in Eindhoven (Noord-Brabant).

In the 20th century, the first nuclear installation in Belgium, the SCK•CEN, was built in Mol in 1962. The European Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM) was founded in Geel in 1957. Pharmaceutical industry was founded in Beerse in the 1960s, with Janssen Pharmaceutica and more recently with Genzyme in Geel. Soudal (silicon) in Turnhout and Ravago (plastics) in Arendonk became leading companies in their markets. Wide open spaces with scarce population also led to the establishment of several military bases, such as the army installations at Leopoldsburg and Brasschaat, and the air bases of Kleine Brogel, Oostmalle, Weelde and Zutendaal.

Due to the exploitation of the Campine coal basin, especially after World War II, new industrial activity was established, such as in Geel, Beringen and Genk. The Belgian village of Malle is called Heart of the Campine', while Westerlo and Kasterlee are called Pearl of the Campine. The most picturesque villages in the Dutch, Northern-Brabant Campine are Oirschot, Eersel and Hilvarenbeek. The other villages have lost much of their historical elements in their course towards industrialisation. In the Dutch Campine eight villages are located which are known under the name acht zaligheden (E: eight blessed ones). The denomination zaligheden has been borrowed from the sel, which is at the end of the name of seven of these eight villages selligheden).

In the Campine there are still a number of bunches, marshes, heathlands and pastures. Large areas of the region were also covered with pine which was used in the coalmines of Wallonia and Limburg. The first pine in the Campine was sown in the Gierlebos in Vosselaar by Adriaan Ghys for Amalia van Solms in 1667.[6] Where the Campine, up to around 1960 includes mainly heathland, oak grove and marsh, these were modified by heavy fertilisation and building activities and were gradually changed into a rather small-scale landscape. Here and there still up to several dozen acres of large heathland - and forests, such as the Kalmthoutse Heide (E: Kalmthout heathland) at Kalmthout, Belgium, the De Maten in Genk, De Zegge (Geel), Zwart Water (Lichtaart), the Zwart Water moors (Turnhout), the Liereman (Oud-Turnhout) and the Prinsenpark (Retie). The natural reserves De Teut in Zonhoven and Ter Haagdoornheide in Houthalen-Helchteren and the Nationaal Park Hoge Kempen. At the border with Belgium in the Dutch part of Campine near Bladel there is natural landscape area with heathland such as Cartierheide and De Pals and Kroonvense Heide. To the North, the area between Boxtel and Oisterwijk is called Kampina. In a number of villages one can still see the typical Campine langgevelboerderijen (long-facade farms).

Trivia

- The Kempenaar singer Louis Neefs released the relatively well known song "M'n dorp in de Kempen" ("My village in the Campine") in 1966.[7]

- SS. La Campine (2,595 GRT), was built by Palmers' SB. & Iron Co., Ltd., Newcastle for F. Speth & Co., Antwerp and sailing for the American Petroleum Company. It was a steamship with auxiliary sails, an early oil tanker that was launched in 1892, and was sunk by U-boat UC 50 in North Sea waters (Doggersbank, 56.00 North - 04.57 East) on March 13, 1917, on its way from Rotterdam to New York City. [8]

References

- "First National Park opened – Milestone for Belgium's Countdown 2010". countdown2010. 2006-03-23. Archived from the original on 2011-02-24. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- "The National Park Hoge Kempen" (PDF). Eurosite. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Bijsterveld & Toorians 2018, p. 40.

- Camby, J. (1935) Victor Hugo en Belgique. Paris: L'Ecran du Monde

- Bont, Antonius Petrus de (1958) Dialekt van Kempenland 3 Deel [in ?5 vols.] Assen: van Gorcum, 1958-60. 1962, 1985

- Harry De Kok, Het Turnhout Van Toen, Publ. Marc Van de Wiel, Bruges, 1987, p.112

- "Mijn dorpje in de Kempen". muziekarchief.be.

- https://uboat.net/wwi/ships_hit/3427.html

Bibliography

- Bijsterveld, Arnoud-Jan A.; Toorians, Lauran (2018). "Texandria revisited: In search of a territory lost in time". Rural riches & royal rags? : Studies on medieval and modern archaeology, presented to Frans Theuws. SPA-Uitgevers: 34–42.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kempen (region). |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kempen. |