Caliban (moon)

Caliban /ˈkælɪbæn/ is the second-largest retrograde irregular satellite of Uranus.[10] It was discovered on 6 September 1997 by Brett J. Gladman, Philip D. Nicholson, Joseph A. Burns, and John J. Kavelaars using the 200-inch Hale telescope together with Sycorax and given the temporary designation S/1997 U 1.[1]

Discovery image of Caliban taken by the Hale Telescope in September 1997 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

|

| Discovery site | Hale Telescope at Palomar Obs. |

| Discovery date | 6 September 1997 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Uranus XVI |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkælɪbæn/[2][3] |

Named after | Caliban |

| S/1997 U 2 | |

| Adjectives | Calibanian /kælɪˈbeɪniən/[4] |

| Orbital characteristics[5] | |

| Epoch 27 June 2015 (JD 2457200.5) | |

| Observation arc | 17.96 yr (6,559 d) |

| 7,163,810 km (0.0478871 AU) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0771431 |

| 1.59 yr (579.26 d) | |

| 294.66253° | |

| 0° 37m 17.345s / day | |

| Inclination | 139.90814° (to the ecliptic) 140.878° (to local Laplace plane)[6] |

| 175.21248° | |

| 342.53671° | |

| Satellite of | Uranus |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean diameter | 42+20 −12 km[7] |

| Mass | ~2.5×1017 kg (estimate)[8] |

Mean density | ~1.3 g/cm³ (assumed)[8] |

| 9.948±0.019 hr (double-peaked)[7] 2.66±0.04 hr (single-peaked)[9] | |

| Albedo | 0.22+0.20 −0.12[7] |

| Temperature | ~65 K (mean estimate) |

| 22.0 (V)[7] | |

| 9.160±0.016[7] 9.0[5] | |

Designated Uranus XVI, it was named after the monster character in William Shakespeare's play The Tempest.

Orbit

Uranus · Sycorax · Francisco · Caliban · Stephano · Trinculo

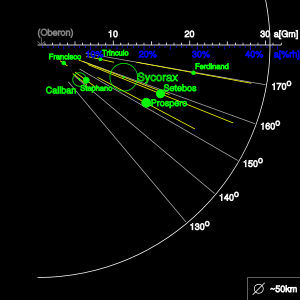

Caliban follows a distant orbit, more than 10 times further from Uranus than the furthest regular moon Oberon.[1] Its orbit is retrograde, moderately inclined and slightly eccentric. The orbital parameters suggest that it may belong to the same dynamic cluster as Stephano and Francisco, suggesting common origin.[11]

The diagram illustrates the orbital parameters of the retrograde irregular satellites of Uranus (in polar co-ordinates) with the eccentricity of the orbits represented by the segments extending from the pericentre to the apocentre.

Physical characteristics

Caliban's diameter is estimated to be around 42 km, based on thermal measurements by the Herschel Space Observatory.[7] Its albedo is estimated at around 0.22, which is unusually high compared to those of other Uranian irregular satellites. Neptune's largest irregular satellite, Nereid, has a similarly high albedo as Caliban.[7]

Somewhat inconsistent reports put Caliban in light-red category (B–V = 0.83 V–R = 0.52,[12] B–V = 0.84 ± 0.03 V–R = 0.57 ± 0.03[11]), redder than Himalia but still less red than most Kuiper belt objects. Caliban may be slightly redder than Sycorax.[9] It also absorbs light at 0.7 μm, and one group of astronomers think this may be a result of liquid water that modified the surface.[13]

Measurements of Caliban's light curve by the Kepler space telescope indicate that its rotation period is about 9.9 hours.[7]

Origin

Caliban is hypothesized to be a captured object: it did not form in the accretionary disk that existed around Uranus just after its formation. The exact capture mechanism is not known, but capturing a moon requires the dissipation of energy. The possible capture processes include: gas drag in the protoplanetary disk, many body interactions and the capture during the fast growth of the Uranus' mass (so-called "pull-down").[10][11]

See also

Footnotes

References

- Gladman Nicholson et al. 1998.

- "Caliban". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Benjamin Smith (1903) The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia

- Apple, Au, & Gandin (2009) The Routledge international handbook of critical education

- "M.P.C. 95215" (PDF). Minor Planet Circular. Minor Planet Center. 29 August 2015.

- Brozovic, M.; Jacobson, R. A. (2009). "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". The Orbits of the Outer Uranian Satellites, Astronomical Journal, 137, 3834. JPL/NASA. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- Farkas-Takács, A.; Kiss, Cs.; Pál, A.; Molnár, L.; Szabó, Gy. M.; Hanyecz, O.; et al. (September 2017). "Properties of the Irregular Satellite System around Uranus Inferred from K2, Herschel, and Spitzer Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 154 (3): 13. arXiv:1706.06837. Bibcode:2017AJ....154..119F. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa8365. 119.

- "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 20 December 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Maris, Michele; Carraro, Giovanni; Cremonese, Gabrielle; Fulle, Marco (May 2001). "Multicolor Photometry of the Uranus Irregular Satellites Sycorax and Caliban". The Astronomical Journal. 121 (5): 2800–2803. arXiv:astro-ph/0101493. Bibcode:2001AJ....121.2800M. doi:10.1086/320378.

- Sheppard, Jewitt & Kleyna 2005.

- Grav, Holman & Fraser 2004.

- Rettig, Walsh & Consolmagno 2001.

- Schmude, Richard (2008). Uranus, Neptune, Pluto and How to Observe Them. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-76601-0.

- Gladman, B. J.; Nicholson, P. D.; Burns, J. A.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Marsden, B. G.; Williams, G. V.; Offutt, W. B. (1998). "Discovery of two distant irregular moons of Uranus". Nature. 392 (6679): 897–899. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..897G. doi:10.1038/31890.

- Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Fraser, Wesley C. (2004-09-20). "Photometry of Irregular Satellites of Uranus and Neptune". The Astrophysical Journal. 613 (1): L77–L80. arXiv:astro-ph/0405605. Bibcode:2004ApJ...613L..77G. doi:10.1086/424997.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rettig, T. W.; Walsh, K.; Consolmagno, G. (December 2001). "Implied Evolutionary Differences of the Jovian Irregular Satellites from a BVR Color Survey". Icarus. 154 (2): 313–320. Bibcode:2001Icar..154..313R. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6715.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D.; Kleyna, J. (2005). "An Ultradeep Survey for Irregular Satellites of Uranus: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (1): 518–525. arXiv:astro-ph/0410059. Bibcode:2005AJ....129..518S. doi:10.1086/426329.