CADASIL

CADASIL or CADASIL syndrome, involving cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, is the most common form of hereditary stroke disorder, and is thought to be caused by mutations of the Notch 3 gene on chromosome 19.[1] The disease belongs to a family of disorders called the leukodystrophies. The most common clinical manifestations are migraine headaches and transient ischemic attacks or strokes, which usually occur between 40 and 50 years of age, although MRI is able to detect signs of the disease years prior to clinical manifestation of disease.[2][3]

| CADASIL | |

|---|---|

| Other names | CADASIL syndrome |

| |

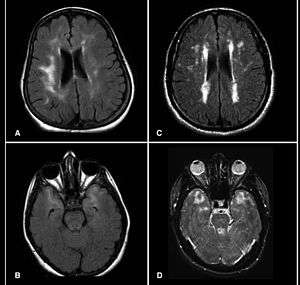

| Brain MRI from patients with CADASIL showing multiple lesions. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, cardiology, medical genetics |

The condition was identified and named by French researchers Marie-Germaine Bousser and Elisabeth Tournier-Lasserve in the 1990s.[4][5]

Signs and symptoms

CADASIL may start with attacks of migraine with aura or subcortical transient ischemic attacks or strokes, or mood disorders between 35 and 55 years of age. The disease progresses to subcortical dementia associated with pseudobulbar palsy and urinary incontinence.

Ischemic strokes are the most frequent presentation of CADASIL, with approximately 85% of symptomatic individuals developing transient ischemic attacks or stroke(s). The mean age of onset of ischemic episodes is approximately 46 years (range 30–70). A classic lacunar syndrome occurs in at least two-thirds of affected patients while hemispheric strokes are much less common. It is worthy of note that ischemic strokes typically occur in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Recurrent silent strokes, with or without clinical strokes, often lead to cognitive decline and overt subcortical dementia. A case of CADASIL presenting as schizophreniform organic psychosis has been reported.[6]

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathology of CADASIL is progressive hypertrophy of the smooth muscle cells in blood vessels. Autosomal dominant mutations in the Notch 3 gene (on the long arm of chromosome 19) cause an abnormal accumulation of Notch 3 at the cytoplasmic membrane of vascular smooth muscle cells both in cerebral and extracerebral vessels,[7] seen as granular osmiophilic deposits on electron microscopy.[8] Leukoencephalopathy follows. Depending on the nature and position of each mutation, a consensus significant loss of betasheet structure of the Notch3 protein has been predicted using in silico analysis.[9]

Diagnosis

MRIs show hypointensities on T1-weighted images and hyperintensities on T2-weighted images, usually multiple confluent white matter lesions of various sizes, are characteristic. These lesions are concentrated around the basal ganglia, peri-ventricular white matter, and the pons, and are similar to those seen in Binswanger disease.[2][10] These white matter lesions are also seen in asymptomatic individuals with the mutated gene.[11] While MRI is not used to diagnose CADASIL, it can show the progression of white matter changes even decades before onset of symptoms.

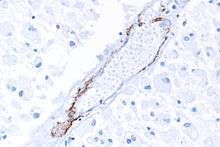

The definitive test is sequencing the whole Notch 3 gene, which can be done from a sample of blood. However, as this is quite expensive and CADASIL is a systemic arteriopathy, evidence of the mutation can be found in small and medium-size arteries. Therefore, skin biopsies are often used for the diagnosis.[12][13]

Treatment

No specific treatment for CADASIL is available. While most treatments for CADASIL patients' symptoms – including migraine and stroke – are similar to those without CADASIL, these treatments are almost exclusively empiric, as data regarding their benefit to CADASIL patients is limited.[14] Antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, dipyridamole, or clopidogrel might help prevent strokes; however, anticoagulation may be inadvisable given the propensity for microhemorrhages.[15] Control of high blood pressure is particularly important in CADASIL patients.[14] Short-term use of atorvastatin, a statin-type cholesterol-lowering medication, has not been shown to be beneficial in CADASIL patients' cerebral hemodynamic parameters,[16] although treatment of comorbidities such as high cholesterol is recommended.[17] Stopping oral contraceptive pills may be recommended.[18] Some authors advise against the use of triptan medications for migraine treatment, given their vasoconstrictive effects,[19] although this sentiment is not universal.[17] In this regard, the advent of the "Ditans" such as Lasmiditan, lacking vasoconstrictive effect, and the "Gepants" such as Ubrogepant and Rimegepant, are attractive alternatives, albeit not yet field-tested in this condition. As with other individuals, people with CADASIL should be encouraged to quit smoking.[20]

In one small study, around 1/3 of patients with CADASIL were found to have cerebral microhemorrhages (tiny areas of old blood) on MRI.[15]

L-arginine, a naturally occurring amino acid, has been proposed as a potential therapy for CADASIL,[21] but as of 2017 there are no clinical studies supporting its use.[18] Donepezil, normally used for Alzheimer's Disease, was not shown not to improve executive functioning in CADASIL patients.[22]

In popular culture

John Ruskin has been suggested to have suffered from CADASIL.[23] Ruskin reported in his diaries having visual disturbances consistent with the disease, and it has also been suggested that it might have been a factor in causing him to describe James Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket as "ask[ing] two hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face". This resulted in the famous libel trial that resulted in a jury's awarding Whistler one farthing damages.[23]

Recent research into the illness of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche has suggested that his mental illness and death may have been caused by CADASIL rather than tertiary syphilis.[24] Likewise, the early death of the composer Felix Mendelssohn, at age 37, from a stroke has been potentially linked to CADASIL. His sister, Fanny Mendelssohn, was similarly affected.[25]

See also

References

- Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, et al. (October 1996). "Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia". Nature. 383 (6602): 707–10. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..707J. doi:10.1038/383707a0. PMID 8878478.

- Chabriat H, Vahedi K, Iba-Zizen MT, et al. (October 1995). "Clinical spectrum of CADASIL: a study of 7 families. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy". Lancet. 346 (8980): 934–9. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91557-5. PMID 7564728.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 545. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- "History of CADASIL".

- Chabriat, H.; Joutel, A.; Vahedi, K.; Iba-Zizen, M. T.; Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Bousser, M. G. (1996). "[CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy)] - Abstract". Journal des Maladies Vasculaires. 21 (5): 277–82. PMID 9026542.

- Ho, Cyrus S.H.; Mondry, Adrian (2015). "CADASIL presenting as schizophreniform organic psychosis". General Hospital Psychiatry. 37 (3): 273.e11–273.e13. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.02.006. PMID 25824603.

- Joutel A, Andreux F, Gaulis S, et al. (March 2000). "The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients". J. Clin. Invest. 105 (5): 597–605. doi:10.1172/JCI8047. PMC 289174. PMID 10712431.

- Ruchoux MM, Guerouaou D, Vandenhaute B, Pruvo JP, Vermersch P, Leys D (1995). "Systemic vascular smooth muscle cell impairment in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy". Acta Neuropathol. 89 (6): 500–12. doi:10.1007/BF00571504. PMID 7676806.

- Vlachakis D, Champeris Tsaniras S, Ioannidou K, Papageorgiou L, Baumann M, Kossida S (October 2014). "A series of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL; insights from 3D molecular modelling and evolutionary analyses". Journal of Molecular Biochemistry. 3 (3): 97–105.

- Ropper AH, Brown RH, eds. (2005). "Cerebrovascular Diseases". Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-141620-7.

- Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A, Melki J, et al. (March 1993). "Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy maps to chromosome 19q12". Nat. Genet. 3 (3): 256–9. doi:10.1038/ng0393-256. PMID 8485581.

- Joutel A, Favrole P, Labauge P, et al. (December 2001). "Skin biopsy immunostaining with a Notch3 monoclonal antibody for CADASIL diagnosis". Lancet. 358 (9298): 2049–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07142-2. PMID 11755616.

- Ueda M, Nakaguma R, Ando Y (March 2009). "[Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL)]". Rinsho Byori (in Japanese). 57 (3): 242–51. PMID 19363995.

- André, Charles (April 2010). "CADASIL: pathogenesis, clinical and radiological findings and treatment". Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 68 (2): 287–99. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2010000200026. PMID 20464302.

- Lesnik Oberstein, S. A.; van den Boom, R.; van Buchem, M. A.; van Houwelingen, H. C.; Bakker, E.; Vollebregt, E.; Ferrari, M. D.; Breuning, M. H.; Haan, J. (2001-09-25). "Cerebral microbleeds in CADASIL". Neurology. 57 (6): 1066–1070. doi:10.1212/wnl.57.6.1066. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 11571335.

- Peters, N (15 September 2007). "Effects of short term atorvastatin treatment on cerebral hemodynamics in CADASIL". J Neurol Sci. 260 (1–2): 100–105. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.015. PMID 17531269.

- Rutten, Julie; Lesnik Oberstein, Saskia AJ (1 January 1993). "Cadasil". In Pagon, Roberta A.; Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Wallace, Stephanie E.; Amemiya, Anne; Bean, Lora JH; Bird, Thomas D.; Ledbetter, Nikki; Mefford, Heather C.; Smith, Richard JH; Stephens, Karen (eds.). GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301673 – via PubMed.

- "Questions about cadasil".

- "CADASIL - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)".

- "CADASIL - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program".

- Peters, N (August 2008). "Enhanced L-arginine-induced vasoreactivity suggests endothelial dysfunction in CADASIL". Journal of Neurology. 255 (8): 1203–1208. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0876-9. PMID 18537053.

- Susman, Ed (2008-04-03). "Donepezil Fails to Improve Cognition in Patients with CADASI... : Neurology Today". Neurology Today. 8 (7): 25. doi:10.1097/01.NT.0000316148.27827.bc.

- Kempster PA, Alty JE (September 2008). "John Ruskin's relapsing encephalopathy". Brain. 131 (Pt 9): 2520–5. doi:10.1093/brain/awn019. PMID 18287121.

- Hemelsoet D, Hemelsoet K, Devreese D (March 2008). "The neurological illness of Friedrich Nietzsche". Acta Neurol Belg. 108 (1): 9–16. PMID 18575181.

- "Blogger".

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CADASIL syndrome. |

- Lesnik Oberstein SA, Boon EM, Terwindt GM (June 28, 2012). CADASIL. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301673. NBK1500. In Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al., eds. (1993). GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle WA: University of Washington, Seattle.

External links

- Patient Organizations worldwide:

- cureCADASIL (US)

- CADASIL Support UK

- asociacion cadasil espana (Spain)

- United Leukodystrophy Foundation: CADASIL

- A patient story at The New York Times

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |