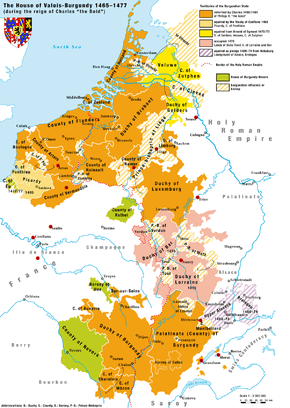

Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The Duke of Burgundy was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy and, after 1482, of the House of Habsburg. Given that the Dukes of Burgundy lost Burgundy proper to the Kingdom of France in 1477, and were never able to recover it, they moved their court to the Low Countries. The Burgundian Low Countries were ultimately expanded to include Seventeen Provinces under Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. The Burgundian inheritance then passed to Philip II of Spain, whose rule was contested by the Dutch revolt, and fragmented into the Spanish Netherlands and the Dutch republic.

Background

Around the 13th and early 14th century, various Dutch cities became so important that they started playing a major role in the political and economical affairs of their respective fiefs.[1] At the same time, the political system of relatively petty lords was ending, and stronger rulers (with actual power over larger territories) started to emerge. In the case of the Dutch, these two developments resulted in the political unification of all Dutch fiefs within a supra-regional state. This process started in the 14th century, with the Flemish cities gaining previously unseen powers over their county. When Louis II, Count of Flanders, died without a male heir, these cities (Bruges, Ypres, and Ghent) arranged a marriage between his daughter and the Duke of Burgundy. By doing this, they set in motion a chain of events eventually leading to the establishment and expansion of the Burgundian Low Countries.

Timeline of expansion

Under Valois-Burgundy

- In 1384, Philip the Bold acquired the county of Flanders, Artois, and the Franche-Comté by the death of his father-in-law, Louis II of Flanders, whose daughter and heiress Margaret was Philip's wife.

- In 1421, Philip the Good (the grandson of Philip the Bold) buys the County of Namur from John III, Marquis of Namur.

- In 1430, Philip of Brabant died childless, leaving his cousin Philip the Good as his heir in Brabant, Lothier, and Limburg.

- In 1432, the Hook and Cod wars ended in victory for the Hollandic cities, Philip the Good was offered to become count of Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut.

- In 1443, Philip conquers the Duchy of Luxembourg

- In 1456, Philip managed that his illegitimate son, David, was elected Bishop of Utrecht, leading to the First and Second Utrecht Civil War.

- In 1456, he also had his nephew Louis of Bourbon become Prince-Bishop of Liège, leading to the Liège Wars.

- In 1473, Philip's son, Charles the Bold buys the Duchy of Guelders from Duke Arnold. However, the house of Burgundy lost this title at Charles's death in 1477.

- In 1477, Charles the Bold died fighting an alliance led by the King of France. France annexed the Duchy of Burgundy, but the title Duke of Burgundy remained in titular use, as seen with his only child, his daughter Mary of Burgundy (Mary the Rich).

Under Habsburg

- 1478: Mary the Rich marries Maximilian I of Habsburg.

- 1482: Death of Mary the Rich. Maximilian assumes rule over what are now effectively the Habsburg Netherlands. Artois ceded to France by the Treaty of Arras.

- 1493: Treaty of Senlis. Artois and St. Pol back in Habsburg hands. Flanders becomes a fief of the Holy Roman Empire.

- 1506: Maximilian and Mary's grandson Charles of Ghent inherits his family's Burgundian lands and becomes Lord of the Netherlands.

- 1516/1519. Charles becomes King of Spain, Archduke of Austria and Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V.

- 1521: Charles V conquers Tournai and the Tournaisis, until then under French influence.

- 1524: Charles conquers Friesland, renamed Lordship of Frisia, during the Guelders Wars.

- 1528: Charles liberates the Bishopric of Utrecht and its lands in Overijssel, then annexes them as Lordship of Utrecht and Lordship of Overijssel, during the Guelders Wars.

- 1536: Charles conquers the Lordship of Groningen and County of Drenthe, during the Guelders Wars.

- 1543: Charles reclaims and conquers the Duchy of Guelders and the County of Zutphen (in personal union), during the Guelders Wars.

- 1549: Pragmatic Sanction creates the Seventeen Provinces.

- 1555/1556: Charles V transfers the Seventeen Provinces to Philip II of Spain. Establishment of the Spanish Netherlands.

Politically, the Burgundian and Habsburg periods were of tremendous importance to the Dutch, as the various Dutch fiefs were now united politically into one single entity.[2] The period ended in great turmoil, as the rise of Protestantism, the centralist policies of the Habsburg Empire, and other factors resulted in the Dutch Revolt and the Eighty Years' War.

See also

References

- "Low Countries, 1000–1400 A.D.", in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000

- Chapter 3, Forming Political Unity, paragraph 3; The Age of Habsburg (1477–1588).