Buyeo

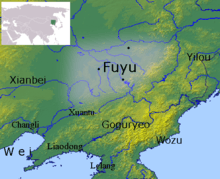

Buyeo, Puyŏ or Fuyu (Korean: 부여; Hanja: 夫餘 Korean pronunciation: [pu.jʌ]; Chinese: 夫餘; pinyin: Fūyú), was an ancient Northeast Asia kingdom centred around the middle of Manchuria and existing as an independent polity from before the late 2nd century BC to the mid-4th century AD.[1]

Buyeo 부여(夫餘) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd century BC–494 AD | |||||||||||

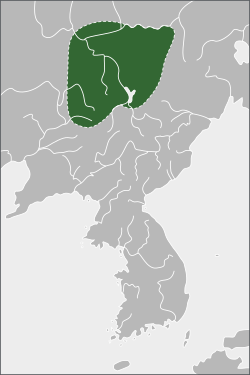

Map of Buyeo (3rd century) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Buyeo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Buyeo language | ||||||||||

| Religion | Shamanism, Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| List of monarchs of King | |||||||||||

• ?–? | Hae Mo-su? | ||||||||||

• 86-48 BC | Hae Buru | ||||||||||

• ?–494 AD | Jan (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | ||||||||||

• Established | 2nd century BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 494 AD | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||

| Buyeo | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 夫餘 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 夫余 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | |||||||

| Hanja | |||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Korea | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Prehistoric period | ||||||||

| Ancient period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Proto–Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Northern and Southern States period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Later Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Dynastic period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Modern period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

|

Ancient period

|

|

Modern period |

The state entered into formal diplomatic relations with the Eastern Han dynasty by the mid-1st century AD as an important ally of that empire to check the Xianbei and Goguryeo threats.[2] After an incapacitating Xianbei invasion in 285, Buyeo was restored with help from the Jin dynasty. This, however, marked the beginning of a period of decline. A second Xianbei invasion in 346 finally destroyed the state, except some remnants in its core region which survived as vassals of Goguryeo until their final annexation in 494.

Both Goguryeo and Baekje, two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, considered themselves Buyeo's successors.

Mythical Origins

The mythical founder of the Buyeo kingdom was Hae Mo-su, the Dongmyeong of Buyeo which literally means Holy King of Buyeo. After its foundation, (the son of heaven, Korean: 해모수; Hanja: 解慕漱) brought the royal court to his new palace, and they proclaimed him King.

Jumong is described as the son of Hae Mo-su and Lady Yuhwa (Korean: 유화부인; Hanja: 柳花夫人), who was the daughter of Habaek (Korean: 하백; Hanja: 河伯), the god of the Amnok River or, according to an alternative interpretation, the sun god Haebak (Korean: 해밝).[3][4][5][6]

History

Archaeological Predecessors

The Buyeo state emerged from the Bronze Age polities of the Seodansan and Liangquan archaeological cultures in the context of trade with various Chinese polities.[7] In particular was the state of Yan which introduced iron technology to Manchuria and the Korean peninsula after its conquest of Liaodong in the early third century BC.

Relations with China

Buyeo became a vassal of Eastern Han in 49 AD.[8] This was advantageous to the Chinese as an ally in the northeast would curb the threats of the Xianbei in western Manchuria and eastern Mongolia and Goguryeo in the Liaodong region and the northern Korean peninsula.[2]

The Buyeo elites also sought this arrangement as it legitimized their rule and gave them better access to Chinese prestige trade goods.

During a period of turmoil in China's northeast, Buyeo attacked the some of Eastern Han's holdings in 111, but relations were mended in 120 and a military alliance was arranged. Two years later Buyeo saved the Xuantu commandery from total destruction by Goguryeo when it sent reinforcement to break the siege of the commandery seat.[9]

In 167 Buyeo attacked the Xuantu commandery but was defeated. Relations were again restored in 174.

In the early 3rd century, Gongsun Du, a Chinese warlord in Liaodong, supported Buyeo to counter Xianbei in the north and Goguryeo in the east. After destroying the Gongsun family, the northern Chinese state of Cao Wei sent Guanqiu Jian to attack Goguryeo. Part of the expeditionary force led by Wang Qi (Korean: 왕기; Hanja: 王頎), the Grand Administrator of the Xuantu Commandery, pursued the Guguryeo court eastward through Okjeo and into the lands of the Yilou. On their return journey they were welcomed as they passed through the land of Buyeo. It brought detailed information of the kingdom to China.[10]

In 285 the Murong tribe of the Xianbei, led by Murong Hui, invaded Buyeo,[11] pushing King Uiryeo (依慮) to suicide, and forcing the relocation of the court to Okjeo.[12] Considering its friendly relationship with the Jin Dynasty, Emperor Wu helped King Uira (依羅) revive Buyeo.

Goguryeo's attack sometime before 347 caused further decline. Having lost its stronghold on the Ashi River (within modern Harbin), Buyeo moved southwestward to Nong'an. Around 347, Buyeo was attacked by Murong Huang of the Former Yan, and King Hyeon (玄) was captured.

Fall

According to Samguk Sagi, in 504, the tribute emissary Yesilbu mentions that the gold of Buyeo could no longer be obtainable for tribute as Buyeo had been driven out by the Malgal and the Somna and absorbed into Baekje. It is also shown that the Emperor Xuanwu of Northern Wei wished that Buyeo would regain its former glory.

A remnant of Buyeo seems to have lingered around modern Harbin area under the influence of Goguryeo. Buyeo paid tribute once to Northern Wei in 457–8,[13] but otherwise seems to have been controlled by Goguryeo. In 494, Buyeo were under attack by the rising Wuji (also known as the Mohe, Korean: 물길; Hanja: 勿吉), and the Buyeo court moved and surrendered to Goguryeo.[14]

Jolbon Buyeo

Many ancient historical records indicate the "Jolbon Buyeo" (Korean: 졸본부여; Hanja: 卒本夫餘), apparently referring to the incipient Goguryeo or its capital city.

In 37 BC, Jumong became the first king of Goguryeo. Jumong went on to conquer Okjeo, Dongye, and Haengin, regaining some of Buyeo and former territory of Gojoseon.

Culture

According to the Sanguo Zhi the Buyeo were agricultural people who occupied the northeastern lands in Manchuria beyond the great walls. The aristocratic rulers subject to the king bore the title ka (加) and were distinguished from each other by animal names, such as the dog ka and horse ka.[2]

Buyeo is north of the Long Wall, a thousand li distant from Xuantu; it is contiguous with Goguryeo on the south, with the Eumnu on the east and the Xianbei on the west, while to its north is the Ruo River. It covers an area some two thousand li square, and its households number eight myriads. Its people are sedentary, possessing houses, storehouses, and prisons. With their many tumuli and broad marshes, theirs is the most level and open of the Eastern Barbarian territories. Their land is suitable for cultivation of the five grains; they do not produce the five fruits. Their people are coarsely big; by temperament strong and brave, assiduous and generous, they are not prone to brigandage... For their dress within their state they favor white; they have large sleeves, gowns, and trousers, and on their feet they wear leather sandals... The people of their state are good at raising domestic animals; they also produce famous horses, red jade, sables, and beautiful pearls... For weapons they have bows, arrows, knives, and shields; each household has its own armorer. The elders of the state speak of themselves as alien refugees of long ago. The forts they build are round and have a resemblance to prisons. Old and young, they sing when walking along the road whether it be day or night; all day long the sound of their voice never ceases... When facing the enemy the several ga themselves do battle; the lower households carry provisions for them to eat and drink.[15]

— Sanguo Zhi

Language

Chinese dynastic records state that the languages of Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Okjeo were similar while being very different from the language of the Yilou to the east.[16][17][18][19] The Koguryoic languages are a branch of the Koreanic language family including Buyeo/Goguryeo and Baekje, next to the Han languages (another branch).[20]

Legacy

In the 1930s, Chinese historian Jin Yufu (金毓黻) developed a linear model of descent for the people of Manchuria and northern Korea, from the kingdoms of Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Baekje, to the modern Korean nationality. Later historians of Northeast China built upon this influential model.[21]

Goguryeo and Baekje, two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, considered themselves successors of Buyeo. King Onjo, the founder of Baekje, is said to have been a son of King Dongmyeongseong, founder of Goguryeo. Baekje officially changed its name to Nambuyeo (South Buyeo, Korean: 남부여; Hanja: 南夫餘) in 538.[22]

See also

- List of Korea-related topics

References

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 11, 13. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Doosan Encyclopedia 유화부인 柳花夫人. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- Doosan Encyclopedia 하백 河伯. Doosan Encyclopedia.

- Encyclopedia of Korean Culture 하백 河伯. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- 조현설. "유화부인". Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. National Folk Museum of Korea. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 62, 101. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Ikeuchi, Hiroshi. "The Chinese Expeditions to Manchuria under the Wei dynasty," Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 4 (1929): 71-119. p. 109

- Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall, 《East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History》, Cengage Learning, 2013, pp.101-102

- Hyŏn-hŭi Yi, Sŏng-su Pak, Nae-hyŏn Yun, 《New history of Korea:Korean studies series》, vol.30, Jimoondang, 2005. p.116

- Northeast Asian History Foundation, 《Journal of Northeast Asian History》, Vol.4-1-2, 2007. p.100

- La Universidad de Seúl, 《Seoul Journal of Korean Studies,》, Vol.17, 2004. p.16

- Lee 1992, p. 15-16.

- 人形似夫餘, 言語不與夫餘句麗同. <三国志>

- 挹婁, 古肅愼之國也. 在夫餘東北千餘里, 東濱大海, 南與北沃沮接, 不知其北所極. 土地多山險. 人形似夫餘, 而言語各異. <後漢書>

- 勿吉國在高句麗北, 舊肅愼國也. ... 言語獨異.<魏書>

- 勿吉國在高句麗北, 一曰靺鞨. 言語獨異.<北史>

- Young Kyun Oh, 2005. Old Chinese and Old Sino-Korean

- Byington, Mark. "History News Network | The War of Words Between South Korea and China Over An Ancient Kingdom: Why Both Sides Are Misguided". Hnn.us. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- Il-yeon: Samguk Yusa: Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea, translated by Tae-Hung Ha and Grafton K. Mintz. Book Two, page 119. Silk Pagoda (2006). ISBN 1-59654-348-5

Bibliography

- Lee, Peter H. (1992), Sourcebook of Korean Civilization 1, Columbia University Press