Bridled nail-tail wallaby

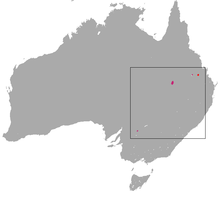

The bridled nail-tail wallaby (Onychogalea fraenata), also known as the bridled nail-tailed wallaby, bridled nailtail wallaby, bridled wallaby, merrin, and flashjack, is a vulnerable species of macropod. It is a small wallaby found in three isolated areas in Queensland, Australia, and whose population is declining. The total population of the species is currently estimated to be less than 500 mature individuals in the wild, and 2285 in captivity.[3]

| Bridled nail-tail wallaby | |

|---|---|

| Female bridled nail-tail wallaby (Onychogalea fraenata) with a joey in its pouch at David Fleay Wildlife Park, Burleigh Heads, Queensland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Onychogalea |

| Species: | O. fraenata |

| Binomial name | |

| Onychogalea fraenata | |

| |

Taxonomy

A specimen was presented to the Linnean Society of London by John Gould in 1840, and published in the society's journal the following year.[2] The date of first publication has been the source of conjecture, and it has been proposed that this was in a 1840 issue of The Athenaeum.[lower-alpha 1][4]

Gould obtained his specimens while in Australia, returning these to England for scientific examination; he gave the animal the common name bridled kangaroo.[5]

Description

These small wallabies are named for two distinguishing characteristics: a white "bridle" line that runs down from the back of the neck around the shoulders, and a horny spur on the end of the tail. Other key physical features include a black stripe running down the dorsum of the neck between the scapulae, large eyes, and white stripes on the cheeks, which are often seen in other species of wallabies as well.

The bridled nail-tail wallaby can grow to one metre in length, half of which is tail, and weighs 4–8 kg. Females are somewhat smaller than the males. The tail spur can be 3–6 mm long and partly covered in hair. Its purpose is unclear.[6]

The "nail-tail" is a feature common to two other species of wallabies: the northern nail-tail wallaby and the crescent nail-tail wallaby (which was declared to be extinct in 1956).

The taste of the meat of this species has been described as excellent.[5]

Distribution and habitat

At the time of European settlement of Australia, bridled nail-tail wallabies were common all along the East Australian coastline region to the west of the Great Dividing Range. Naturalists in the 19th century reported that the species ranged from the Murray River region of Victoria through central New South Wales to Charters Towers in Queensland.[7][8]

The species declined in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with no confirmed sightings between 1937 and 1973, by which time it was believed to be extinct. After reading an article in a magazine about Australia's extinct species, a fencing contractor reported that there was an extant population on a property near Dingo, Queensland.[9][10] This sighting was subsequently confirmed by researchers from the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, and the property eventually became Taunton National Park, a scientific nature reserve for the purpose of ensuring the ongoing survival and protection of this endangered species.[1] The current range of this wallaby is less than 5% of its original range.[11]

Ecology and behaviour

The species are most active during the night-time and dusk periods. Day is usually spent sleeping in hollows near bushes or trees. In modern habitats, nail-tails keep close to the edges of pasture grasses. These wallabies have a reputation as shy and solitary animals. They may occasionally form small groups of up to four to feed together when grazing is in short supply. The bridled nail-tail wallaby likes to avoid confrontation and has two main ways of avoiding threats – hiding in hollow logs and crawling under low shrubs. If caught in the open, it may try to lie completely still hoping not to be observed.

Gould was able to view the animal in its native habitat and recorded observations of its behaviour at the area around Brezi and then to observe their capture by the indigenous people at "Gundermein" on around the lower Namoi River. His notes the rapid movement of a live animal when pursued, outpacing the dogs accompanying his party, which ascended up a hollow tree and leapt from the top to enter a hollow log. At a second site Gould witnessed the capture of the species with nets by the local people, fulfilling his request for a series of specimens.[5]

After a gestation period of about 23 days, the single joey undergoes further development in the mother's pouch for around four more months.

The bridled nail-tail wallaby is of interest to marsupial researchers because it appears to have a more vigorous immune system than other species of macropods. In the words of Central Queensland University based marsupial immunologist Lauren Young, "These wallabies appear to be able to survive parasite infections, viruses and various diseases more readily than other marsupials".[12]

Recovery efforts

Since its rediscovery, the bridled nail-tail wallaby has been the target of private conservation efforts to re-establish viable populations. Captive breeding programs have allowed the establishment of three populations; two in State reserves located at Idalia and Taunton National Parks, and another on a private reserve, Project Kial, located near Marlborough in Central Queensland. The Idalia re-introduction was ultimately a failure, and the species is now refined to three populations: Taunton National Park, Avocet Nature Refuge, and Scotia Sanctuary. The extant population is currently estimated to be less than 500 mature individuals in the wild.[3]

In the early 1900s this species suffered dramatically from shooting, for its fur and because it was considered a pest.[13] Current threats to the species include predation by introduced species such as feral cats, red foxes, and dingoes. Other threats include wildfires, prolonged drought, habitat destruction by the pastoral industry and competition for food from grazers, such as rabbits and domestic sheep.[11]

Footnotes

- The Athenaeum 670:685 [29 August 1840]

- McKnight, M (2008). "Onychogalea fraenata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Cambridge, England. 2008. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- Gould, J. (1841). "On five new species of kangaroo". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1840: 92–94.

- Berry, L. E.; L' Hotellier, F. A.; Carter, A.; Kemp, L.; Kavanagh, R. P.; Roshier, D. A. (2019-02-01). "Patterns of habitat use by three threatened mammals 10 years after reintroduction into a fenced reserve free of introduced predators". Biological Conservation. 230: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2018.11.023. ISSN 0006-3207.

- McAllan, I.A.W.; Bruce, M.D. (1989). "Some problems of vertebrate nomenclature. I. Mammals". Bollettino Museo Regionale di Science Naturali. 7 (2): 443–460.

- Gould, J. (1841). A monograph of the Macropodidæ, or family of kangaroos. The Author.

- Lee K. Curtis (2009), "Kangaroos and Wallabies", Wildlife Australia, 46 (2): 40–41

- Gould, J (1863). "Introduction". An introduction to the mammals of Australia. 2. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 41.

- Collett, R (1887). "On a collection of mammals from central and northern Queensland". Zoologische Jahrbücher (2): 829–940.

- Gordon, G; Lawrie, BC (1980). "The rediscovery of the bridled nail-tailed wallaby, Onychogalea fraenata (Gould) (Marsupialia: Macropodidae)". Australian Wildlife Research. 7 (3): 339–45. doi:10.1071/WR9800339.

- "Bridled nailtail wallaby". State of Queensland (Environmental Protection Agency). Archived from the original on 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- Lundie-Jenkins, G (2002). Recovery for the bridled nailtail wallaby (Onychogalea fraenata) 1997-2001. Report to Environment Australia, Canberra (Report). Brisbane: Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service.

- Dempsey, S (2008). "Animal Magic". Be Magazine. Hardie Grant Magazines for CQUniversity. p. 30.

- "Animal Info - Bridled Nail-tailed Wallaby". Animal Info - Endangered Animals. animalinfo.org. 2005-01-05. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

Further reading

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

External links

- Species Profile and Threats Database: Onychogalea fraenata — Bridled Nail-tail Wallaby, Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

- Bridled Nailtail Wallaby Trust

- Project Kial, A Bridled Nailtail Wallaby Recovery Project, Australian Animals Care & Education Inc. (AACE)