Striped possum

The striped possum or common striped possum (Dactylopsila trivirgata) is a member of the marsupial family Petauridae.[2] The species is black with three white stripes running head to tail, and its head has white stripes that form a 'Y' shape. It is closely related to the sugar glider, and is similar in appearance.

| Striped possum | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Cooktown, Queensland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Petauridae |

| Genus: | Dactylopsila |

| Species: | D. trivirgata |

| Binomial name | |

| Dactylopsila trivirgata Gray, 1858 | |

| |

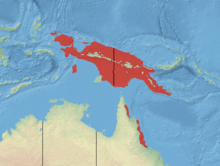

| Distribution of the striped possum | |

Taxonomy

.jpg)

The striped possum was first described by John Edward Gray in 1858 from a specimen sent from the Aru Islands (in Indonesia) to the British Museum by Alfred Russel Wallace.[3] Gray gave the species the name Dactylopsila trivirgata in 1858,[4] the name the species retains today. The illustration that appeared alongside the first description was produced by Joseph Wolf.

Range

The striped possum lives in rainforests and eucalypt woodland along the east coast of Cape York Peninsula and as far south as Townsville in Queensland, Australia, but is more commonly found in New Guinea,[2] as well as several other small islands in the area (including the Solomon Islands). Uncommon and rarely seen in Australia.[5]

Description

This possum looks like a black and white squirrel. It is solitary, mostly nocturnal, arboreal, and builds nests in tree branches.[6] The body length is approx. 263 mm long, tail 325 mm, and weight 423 g.[7] The striped possum's tail is prehensile.[2] Its fourth finger is elongated relative to the others (like the third finger of the aye-aye, a lemur found in Malagasy rainforests) and is used to take beetles and caterpillars from tree bark,[8] making it a "mammalian woodpecker".[9] The striped possum also eats leaves, fruits, and small vertebrates.[2] Its main diet consists of wood-boring insect larvae, which are extracted from rotten branches probing with its elongated fourth finger and its powerful incisor teeth which are used to rip open tree bark to expose insects. It detects the larvae by a rapid drumming along branches with the toes of its forefoot.[5] The fourth finger has an unusual hooked nail which it uses to extract insects out of cracks.[10]

It emits a "very powerful unpleasant smell."[10] It is noisy and growls. During the day it curls up on an exposed branch and sleeps.[11]

The female striped possum has two teats in her pouch and can give birth to up to two young.[2] However, not a lot is known of its breeding habits.

It is most easily found by the sound it makes chewing and drinking in the forest. The striped possum is one of the least known marsupials. The species is not considered to be threatened.

Footnotes

- Salas, L.; Dickman, C.; Helgen, K.; Burnett, S.; Martin, R. (2016). "Dactylopsila trivirgata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6226A21960093. Retrieved 11 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKay, G. (Ed.). (1999). Mammals (p. 60). San Francisco: Weldon Owen Inc. ISBN 1-875137-59-9

- Gray, John Edward (1858). "List of species of Mammalia sent from the Aru Islands by Mr A.R. Wallace to the British Museum". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 26: 106–113. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1858.tb06350.x – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Marlow (1981), p. 80.

- Marlow (1981), p. 80,

- Ryan and Burwell (20000), p. 339.

- Rawlins, D. R.; Handasyde, K. A. (2002). "The feeding ecology of the striped possum Dactylopsila trivirgata (Marsupialia: Petauridae) in far north Queensland, Australia". J. Zool. Lond. Zoological Society of London. 257 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1017/S0952836902000808. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- Beck, R. M. D. (2009). "Was the Oligo-Miocene Australian metatherian Yalkaparidon a 'mammalian woodpecker'?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. The Linnean Society of London. 97: 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01171.x. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- Drury (1981), p. 71.

- Ryan and Burwell (2000), p. 339.

References

- Drury, Susan (1981) Native Animals of Australia. Macmillan Pocket Guide. Macmillan Company of Australia, Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 0-333-33755-7.

- Marlow, Basil (1981). Marsupials of Australia. Amended edition. First published in 1962. Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, Western Australia.

- Ryan, Michelle and Chris Burwell, editors (2000). Wildlife of Tropical North Queensland. Queensland Museum, Brisbane. ISBN 0-7242-9349-3.

- Briggs, Mike; Briggs, Peggy (2004). The Encyclopedia of World Wildlife. Paragon. ISBN 1-4054-3679-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Striped possum. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Striped possum |