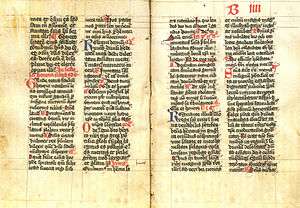

Breviary

A breviary (Latin: breviarium) is a liturgical book used in Western Christianity for praying the canonical hours.[1]

Historically, different breviaries were used in the various parts of Christendom, such as Aberdeen Breviary, Belleville Breviary, Stowe Breviary and Isabella Breviary, although eventually the Roman Breviary became the standard within the Roman Catholic Church.[2]

History

In the Catholic Church, Pope Nicholas III approved a Franciscan breviary, for use in that religious order, and this was the first text that bore the title of breviary.[1] However, the "contents of the breviary, in their essential parts, are derived from the early ages of Christianity", consisting of psalms, Scripture lessons, writings of the Church Fathers, as well as hymns and prayers.[3] The ancient breviary of the Bridgettines had been in use for more than 125 years before the Council of Trent and so was exempt from the Constitution of Pope Pius V which abolished the use of breviaries differing from that of Rome.[4]

In Lutheran usage, the Diakonie Neuendettelsau religious institute uses a breviary unique to the order; For All the Saints: A Prayer Book for and by the Church, among many other breviaries such as The Daily Office: Matins and Vespers, Based on Traditional Liturgical Patterns, with Scripture Readings, Hymns, Canticles, Litanies, Collects, and the Psalter, Designed for Private Devotion or Group Worship, are popular in Lutheran usage as well.[5]

Now translated from Latin, The Syon Breviary (Daily Office of Our Lady) has been published in English for the first time, with plainchant music, to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the foundation of Syon Abbey in 1415 by King Henry V. Following the Oxford Movement in the Anglican Communion, in 1916, the Anglican Breviary was published by the Frank Gavin Liturgical Foundation.[6]

See also

References

- Palazzo, Eric (1998). A History of Liturgical Books from the Beginning to the Thirteenth Century. Liturgical Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780814661673.

It is the Franciscan breviary deriving from the second rule of the order approved by Innocent III in 1223 that for the first time expressly bears the name breviarium: Clerici facient divinum offocoum secundum ordinem sanctae Romanae Ecclesia excepto Psalterio, ex quo habere poterunt breviaria ["The clerics will celebrate the Office according to the ordo of the holy Roman Church, except for the psalter which they may use in shortened forms"].

- Lewis, George (1853). The Bible, the missal, and the breviary; or, Ritualism self-illustrated in the liturgical books of Rome. T. & T. Clark. p. 71.

The Goths of Spain had their Breviary; the French Church had its Breviary; England—"the Breviary of Salisbury"—and Scotland, "the Breviary of Aberdeen"—all which, along with many more evidences of the independence of national churches, Rome has laboured to obliterate by commanding the exclusive use of the Roman Breviary, and thus extinguishing every appearance of a divided worship, and of independent national and self-regulated churches.

- Smith, William; Cheetham, Samuel (1 January 2005). Encyclopædic Dictionary Of Christian Antiquities. Concept Publishing Company. p. 247. ISBN 9788172681111.

The contents of the breviary, in their essential parts, are derived from the early ages of Christianity. They consist of psalms, lessons taken from the Scriptures, and from the writings of the Fathers, versicles and pious sentences thrown into the shape of the antiphons, responses, or other analogous forms, hymns and prayers.

- The Tablet, 29th May, 1897, page 27.

- Mayes, Benjamin T. G. (5 September 2004). "Daily Prayer Books in the History of German and American Lutheranism" (PDF). Lutheran Liturgical Prayer Brotherhood. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Hart, Addison H. ""Prayer Rhythms" Redivivus". Touchstone. The Fellowship of St. James. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

The Reverend Frank Gavin had himself suggested such a work as early as 1916.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Breviaries. |

| Look up breviary in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The 1911 Roman Breviary in Latin and English

- The Syon Breviary — Daily Office of Our Lady — (Bridgettine) Now in English

- The Anglican Breviary

- Lewis E 49 Breviary at OPenn

- Lewis E 50 Breviary, Use of Ghent at OPenn

- Lewis E 51 Breviary at OPenn

- Lewis E 52 Breviary at OPenn

- Lewis E 236 Breviary at OPenn

- Lewis E 256 Breviary, Cistercian use at OPenn

- MS 240/15 Breviary, Cistercian Use at OPenn

- MS 75 Breviary, Paris, ca. 1260-1300 at Library of Congress