Boxer (dog)

The Boxer is a medium to large, short-haired breed of dog, developed in Germany. The coat is smooth and tight-fitting; colors are fawn, brindled, or white, with or without white markings. Boxers are brachycephalic (they have broad, short skulls), have a square muzzle, mandibular prognathism (an underbite), very strong jaws, and a powerful bite ideal for hanging on to large prey. The Boxer was bred from the Old English Bulldog and the now extinct Bullenbeisser which became extinct by crossbreeding rather than by a decadence of the breed. The Boxer is part of the Molosser group. This group is a category of solidly built, large dog breeds that all descend from the same common ancestor, the large shepherd dog known as a Molossus. The Boxer is a member of the Working Group.[4]

| Boxer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fawn boxer, uncropped and undocked | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | Germany | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The first Boxer club was founded in 1895, with Boxers being first exhibited in a dog show for St. Bernards in Munich the next year. Based on 2013 American Kennel Club statistics, Boxers held steady as the seventh-most popular breed of dog in the United States for the fourth consecutive year.[5] However, according to the AKC's website,[6] the boxer is now the eleventh-most popular dog breed in the United States.

Appearance

.jpg)

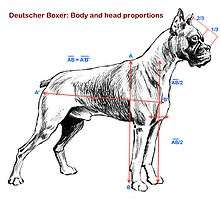

The head is the most distinctive feature of the Boxer. The breed standard dictates that it must be in perfect proportion to the body and above all it must never be too light.[7] The greatest value is to be placed on the muzzle being of correct form and in absolute proportion to the skull. The length of the muzzle to the whole of the head should be a ratio of 1:3. Folds are always present from the root of the nose running downwards on both sides of the muzzle, and the tip of the nose should lie somewhat higher than the root of the muzzle. In addition a Boxer should be slightly prognathous, i.e., the lower jaw should protrude beyond the upper jaw and bend slightly upwards in what is commonly called an underbite or "undershot bite".[8]

Boxers were originally a docked and cropped breed, and this is still done in some countries.[9] However, due to pressure from veterinary associations, animal rights groups, and the general public, both cropping of the ears and docking of the tail have been prohibited in many countries around the world. A line of naturally short-tailed (bobtail) Boxers was developed in the United Kingdom in anticipation of a tail docking ban there;[10] after several generations of controlled breeding, these dogs were accepted in the Kennel Club (UK) registry in 1998, and today representatives of the bobtail line can be found in many countries around the world. However, in 2008 the FCI added a "naturally stumpy tail" as a disqualifying fault in their breed standard, meaning those Boxers born with a bobtail can no longer be shown in FCI member countries. In the United States and Canada as of 2012, cropped ears are still more common in show dogs, even though the practice of cosmetic cropping is currently opposed by the American Veterinary Medical Association.[11] In March 2005 the AKC breed standard was changed to include a description of the uncropped ear, but to severely penalize an undocked tail. The tail of a boxer is typically docked before the cartilage is fully formed, between 3–5 days old.[12] The procedure does not require any sutures when performed at this young age and anesthesia is not used.

Coat and colors

The Boxer is a short-haired breed, with a smooth coat that lies tight to the body. The recognized colors are fawn and brindle,[4] frequently with a white underbelly and white on the feet. These white markings,[13] called flash, often extend onto the neck or face, and dogs that have these markings are known as "flashy". "Fawn" denotes a range of color, the tones of which may be described variously as light tan or yellow, reddish tan, mahogany or stag/deer red, and dark honey-blonde. In the UK and Europe, fawn Boxers are typically rich in color and are often called "red". "Brindle" refers to a dog with black stripes on a fawn background. Some brindle Boxers are so heavily striped that they give the appearance of "reverse brindling", fawn stripes on a black body; these dogs are conventionally called "reverse brindles", but that is actually a misnomer—they are still fawn dogs with black stripes. In addition, the breed standards state that the fawn background must clearly contrast with or show through the brindling.

The Boxer does not carry the gene for a solid black coat color and therefore purebred black Boxers do not exist.[14]

- The color brindle can be with or without white markings

A red fawn boxer

A red fawn boxer "Reverse" brindle Boxer, cropped and docked

"Reverse" brindle Boxer, cropped and docked

White Boxers

Boxers with white markings covering more than one-third of their coat – conventionally called "white" Boxers – are neither albino nor rare; approximately 20–25% of all Boxers born are white.[15] Genetically, these dogs are either fawn or brindle, with excessive white markings overlying the base coat color. Like fair-skinned humans, white Boxers have a higher risk of sunburn and associated skin cancers than colored Boxers. The extreme piebald gene, which is responsible for white markings in Boxers, is linked to congenital sensorineural deafness in dogs. It is estimated that about 18% of white Boxers are deaf in one or both ears,[16] though Boxer rescue organizations see about double that number.[17][18]

In the past, breeders often euthanized white puppies at birth. A 1998 study of Boxers in the Netherlands showed that 17% of Boxer pups were euthanized because they were white.[19] Previously, the American Boxer Club "unofficially recommended euthanasia for these animals."[20] Reasons for euthanizing white pups includes the view that it is unethical to sell a dog with "faults" and the perception that white Boxers are at higher risk of ending up abandoned in rescues.[21] Today, breeders are increasingly reluctant to euthanize healthy pups[20] and may choose to neuter and place them in pet homes instead.

White boxer.

White boxer. The side-view of another white boxer.

The side-view of another white boxer.

Temperament

The character of the Boxer is of the greatest importance and demands the most solicitous attention. He is renowned from olden times for his great love and faithfulness to his master and household. He is harmless in the family, but can be distrustful of strangers, bright and friendly of temperament at play, but brave and determined when aroused. His intelligence and willing tractability, his modesty and cleanliness make him a highly desirable family dog and cheerful companion. He is the soul of honesty and loyalty, and is never false or treacherous even in his old age.

— 1938 AKC Boxer breed standard[22]

Boxers are a bright, energetic and playful breed and tend to be very good with children.[4] They are patient and spirited with children but also protective, making them a popular choice for families.[4] They are active, strong dogs that require adequate exercise to prevent boredom-associated behaviors such as chewing, digging, or licking. Boxers have earned a slight reputation of being "headstrong," which can be related to inappropriate obedience training. Owing to their intelligence and working breed characteristics, training based on corrections often has limited usefulness. Boxers, like other animals, typically respond better to positive reinforcement techniques such as clicker training, an approach based on operant conditioning and behaviorism, which offers the dog an opportunity to think independently and to problem-solve.[23][24] Stanley Coren's survey of obedience trainers, summarized in his book The Intelligence of Dogs, ranked Boxers at #48 – average working/obedience intelligence. Many who have worked with Boxers disagree quite strongly with Coren's survey results, and maintain that a skilled trainer who uses reward-based methods will find Boxers have far above-average intelligence and working ability.[23][24][25]

The Boxer by nature is not an aggressive or vicious breed. It is an instinctive guardian and can become very attached to its family. Like all dogs, it requires proper socialization.[26] Boxers are generally patient with smaller dogs and puppies, but difficulties with larger adult dogs, especially those of the same sex, may occur. Boxers are generally more comfortable with companionship, in either human or canine form. Boxers are very patient and are great to adopt as family dogs because they are good with children and people of all kinds.[27]

Brindle boxer head

Brindle boxer head- Brindle boxer head with white neck

A fawn Boxer puppy

A fawn Boxer puppy A fawn boxer head

A fawn boxer head

History

The Boxer is part of the Molosser dog group, developed in Germany in the late 19th century from the now extinct Bullenbeisser, a dog of Mastiff descent, and Bulldogs brought in from Great Britain.[4] The Bullenbeisser had been working as a hunting dog for centuries, employed in the pursuit of bear, wild boar, and deer. Its task was to seize the prey and hold it until the hunters arrived. In later years, faster dogs were favored and a smaller Bullenbeisser was bred in Brabant, in northern Belgium. It is generally accepted that the Brabanter Bullenbeisser was a direct ancestor of today's Boxer.[28]

In 1894, three Germans by the names of Friedrich Robert, Elard König, and R. Höpner decided to stabilize the breed and put it on exhibition at a dog show. This was done in Munich in 1896, and the year before they founded the first Boxer Club, the Deutscher Boxer Club. The Club went on to publish the first Boxer breed standard in 1904, a detailed document that has not been changed much to this day.[29]

The breed was introduced to other parts of Europe in the late 19th century and to the United States around the turn of the 20th century. The American Kennel Club (AKC) registered the first Boxer in 1904,[4] and recognized the first Boxer champion, Dampf vom Dom, in 1915. During World War I, the Boxer was co-opted for military work, acting as a valuable messenger dog, pack-carrier, attack dog, and guard dog.[4] It was not until after World War II that the Boxer became popular around the world. Taken home by returning soldiers, they introduced the dog to a wider audience and soon became a favorite as a companion, a show dog, and a guard dog.

Early genealogy

The German citizen George Alt, a Munich resident, mated a brindle-colored female dog imported from France named Flora with a local dog of unknown ancestry, known simply as "Boxer", resulting in a fawn-and-white male, named "Lechner's Box" after its owner.

This dog was mated with his own dam Flora, and one of its offspring was a female dog called Alt's Schecken. George Alt mated Schecken with a Bulldog named Dr. Toneissen's Tom to produce the historically significant dog Mühlbauer's Flocki. Flocki was the first Boxer to enter the German Stud Book after winning the aforementioned show for St. Bernards in Munich 1896, which was the first event to have a class specific for Boxers.[28][29]

The white female dog Ch. Blanka von Angertor, Flocki's sister, was even more influential when mated with Piccolo von Angertor (Lechner's Box grandson) to produce the predominantly white (parti-colored) female dog Meta von der Passage, which, even bearing little resemblance with the modern Boxer standard (early photographs depict her as too long, weak-backed and down-faced), is considered the mother of the breed.[30][31] John Wagner, in The Boxer (first published in 1939) said the following regarding this female dog:[32]

Meta von der Passage played the most important role of the five original ancestors. Our great line of sires all trace directly back to this female. She was a substantially built, low to the ground, brindle and white parti-color, lacking in underjaw and exceedingly lippy. As a producing female few in any breed can match her record. She consistently whelped puppies of marvelous type and rare quality. Those of her offspring sired by Flock St. Salvator and Wotan dominate all present-day pedigrees. Combined with Wotan and Mirzl children, they made the Boxer.

Breed name

The name "Boxer" is supposedly derived from the breed's tendency to play by standing on its hind legs and "boxing" with its front paws.[4] According to Andrew H. Brace's Pet owner's guide to the Boxer, this theory is the least plausible explanation.[30] He claims "it's unlikely that a nation so permeated with nationalism would give to one of its most famous breeds a name so obviously anglicised".

German linguistic and historical evidence find the earliest written source for the word Boxer in the 18th century, where it is found in a text in the Deutsches Fremdwörterbuch (The German Dictionary of Foreign Words),[33] which cites an author named Musäus of 1782 writing "daß er aus Furcht vor dem großen Baxer Salmonet ... sich auf einige Tage in ein geräumiges Packfaß ... absentiret hatte". At that time the spelling "baxer" equalled "boxer". Both the verb (boxen [English "to box, to punch, to jab"]) and the noun (Boxer) were common German words as early as the late 18th century. The term Boxl, also written Buxn or Buchsen in the Bavarian dialect, means "short (leather) trousers" or "underwear". The very similar-sounding term Boxerl, also from the Bavarian dialect, is an endearing term for Boxer.[34] More in line with historical facts, Brace states that there exist many other theories to explain the origin of the breed name, from which he favors the one claiming the smaller Bullenbeisser (Brabanter) were also known as "Boxl" and that Boxer is just a corruption of that word.[34]

In the same vein runs a theory based on the fact that there were a group of dogs known as Bierboxer in Munich by the time of the breed's development. These dogs were the result from mixes of Bullenbeisser and other similar breeds. Bier (beer) probably refers to the Biergarten, the typical Munich beergarden, an open-air restaurant where people used to take their dogs along. The nickname "Deutscher Boxer" was derived from bierboxer and Boxer could also be a corruption of the former or a contraction of the latter.[35]

A passage from the book "The Complete Boxer" by Milo G Denlinger states:

It has been claimed that the name "Boxer" was jokingly applied by an English traveler who noted a tendency of the dog to use its paws in fighting. This seems improbable. Any such action would likely result in a badly bitten if not broken leg. On the other hand, a German breeder of forty years' experience states positively that the Boxer does not use his feet, except to try and extinguish a small flame such as a burning match. But a Boxer does box with his head. He will hit (not bite) a cat with his muzzle hard enough to knock it out and he will box a ball with his nose. Or perhaps, since the German dictionary translates 'boxer' as 'prize-fighter' the name was bestowed in appreciation of the fighting qualities of the breed rather than its technique.

Boxer is also the name of a dog owned by John Peerybingle, the main character in the best-selling 1845 book The Cricket on the Hearth by Charles Dickens, which is evidence that "Boxer" was commonly used as a dog name by the early 19th century, before the establishment of the breed by the end of that same century.

The name of the breed could also be simply due to the names of the very first known specimens of the breed (Lechner's Box, for instance).

Health

Leading health issues to which Boxers are prone include cancers, heart conditions such as aortic stenosis and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (the so-called "Boxer cardiomyopathy"),[36] hypothyroidism, hip dysplasia, and degenerative myelopathy and epilepsy; other conditions that may be seen are gastric dilatation volvulus (also known as bloat), intestinal problems, and allergies (although these may be more related to diet than breed).[37][38] Entropion, a malformation of the eyelid requiring surgical correction, is occasionally seen, and some lines have a tendency toward spondylosis deformans, a fusing of the spine,[39] or dystocia.[40] Other conditions that are less common but occur more often in Boxers than other breeds are hystiocytic ulcerative colitis (sometimes called Boxer colitis), an invasive E. coli infection,[41] and indolent corneal ulcers, often called Boxer eye ulcers.

About 22% of puppies die before reaching 7 weeks of age.[42] Stillbirth is the most frequent cause of death, followed by infection. Mortality due to infection increases significantly with increases in inbreeding.[42]

According to a UK Kennel Club health survey, cancer accounts for 38.5% of Boxer deaths, followed by old age (21.5%), cardiac (6.9%) and gastrointestinal (6.9%) related issues. The breed is particularly predisposed to mast cell tumours, a cancer of the immune system.[43] Median lifespan was 10.25 years.[44] Responsible breeders use available tests to screen their breeding stock before breeding, and in some cases throughout the life of the dog, in an attempt to minimize the occurrence of these diseases in future generations.[45]

Boxers are known to be very sensitive to the hypotensive and bradycardiac effects of a commonly used veterinary sedative, acepromazine.[46] It is recommended that the drug be avoided in the Boxer breed.[47]

As an athletic breed, proper exercise and conditioning is important for the continued health and longevity of the Boxer.[4] Care must be taken not to over-exercise young dogs, as this may damage growing bones; however, once mature, Boxers can be excellent jogging or running companions. Because of their brachycephalic head, they do not do well with high heat or humidity, and common sense should prevail when exercising a Boxer in these conditions.

Nutrition

Boxers need plenty of exercise which means their diet should be high in quality calories. The main source of these calories should be lean animal protein, which include lean chicken, turkey, lamb and fish.[48] While on a high calorie diet, owners should be thoughtful of the amount of treats given as this tends to cause obesity.[4] Owners should be mindful of the food to snack ratio being consumed by the Boxer when determining how many treats are acceptable.[48] Some healthy snacks include raw fruits and vegetables.[48]

Boxers are also prone to dental problems, increasing their susceptibility for bad breath; dry dog food that is large and difficult for them to chew improves the likelihood for plaque removal.[49] Plaque can also be removed by crude fiber in kibble, which has a flexible structure that increases chewing time.[50] Polyphosphates are often coated on the outside of dry dog food, which further reduce plaque buildup by preventing calcium production in saliva.[49] Odor production from the boxer's mouth is likely to be reduced if its teeth and oral cavity are kept in healthy conditions.

Uses

.jpg)

Boxers are friendly, lively companions that are popular as family dogs.[4] Their suspicion of strangers, alertness, agility, and strength make them formidable guard dogs. They sometimes appear at dog agility or dog obedience trials and flyball events. These strong and intelligent animals have also been used as service dogs, guide dogs for the blind, therapy dogs, police dogs in K9 units, and occasionally herding cattle or sheep. The versatility of Boxers was recognized early on by the military, which has used them as valuable messenger dogs, pack carriers, and attack and guard dogs in times of war.

Notable Boxers

- Punch and Judy, awarded the Dickin Medal for conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving in military conflict.

References

- "Breed Standard". The Kennel Club. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- American Kennel Club. "Breed Standard".

- Cassidy, Kelly M. "Breed Longevity Data". Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- http://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/boxer/#standard "Get to Know the Boxer", 'The American Kennel Club', Retrieved 14 May 2014

- American Kennel Club. "Registration Statistics".

- http://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/boxer/Club,+American+Kennel.+%22Boxer+Dog+Breed+Information%22.+www.akc.org.+Retrieved+2016-02-05.

- The Worldwide Boxer. "The Boxer Head".

- American Boxer Club Illustrated Standard. "The Boxer Bite". Archived from the original on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- "How People Perceive Dogs With Docked Tails and Cropped Ears". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Bruce Cattanach. "Genetics Can Be Fun".

- American Veterinary Medical Association. "Ear Cropping and Tail Docking of Dogs".

- "The Boxer and Tail Docking". www.pedigree.com. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Sheila Schmutz: Boxer Markings

- "Position statements - black Boxers". American Boxer Club (America). Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Boxer Club of Canada Code of Ethics".

- Cattanach, Bruce. "White Boxers and Deafness". Archived from the original on 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- R.D. Conrad & Ann Gilbert. "Coat Colors in Boxers and the American Boxer Club, Inc".

- Claudia Moder, Green Acres Boxer Rescue of WI. "A Boxer is a Boxer is a Boxer: Deaf Whites in Rescue". Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- Nielen, A. L. J.; Van Der Gaag, I.; Knol, B. W.; Schukken, Y. H. (1998). "Investigation of mortality and pathological changes in a 14.month birth cohort of boxer puppies". Veterinary Record. 142 (22): 602. doi:10.1136/vr.142.22.602.

- "A "White" Paper" (PDF). AKC gazette. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "A proposal for the betterment of our breed". American Boxer Club. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- "1938 AKC Boxer Breed Standard". Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- Karla Spitzer (2006). The Everything Boxer Book (1st ed.). Avon, MA: F+W Publications, Inc. pp. 174–175. ISBN 1-59337-526-3.

- Joan Hustace Walker (2001). Training Your Boxer (1st ed.). Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series, Inc. pp. 7, 11, 16–17. ISBN 0-7641-1634-7.

- Abraham, Stephanie (July 1994). "Your Boxer's IQ: Breaking The Code" (PDF). American Boxer Club/AKC Gazette. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- "Boxer Disposition and Temperament". Boxer-dog.org. 2003-05-24. Retrieved 2006-06-09.

- "Boxer Dog Breed Information". Vetstreet. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- John Wagner. "Short History of the Boxer Breed". Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- Anne Rogers Clark and Andrew H. Brace, ed. (1995). The International Encyclopedia of Dogs (1st ed.). New York, New York: Howell Book house. pp. 140–142. ISBN 0-87605-624-9. OCLC 32697706.

- Brace, Andrew H. (2004). Pet Owner's Guide to the Boxer. Interpet Ltd. ISBN 1-86054-288-3.

- Wagner, John (1939). The Boxer.

- Wagner, John (1950). The Boxer. p. 47.

- Strauss, Gerhard; Kämper-Jensen, Heidrun; Nortmeyer, Isolde (1997). Deutsches Fremdwörterbuch Bd. 3. Berlin: de Gruyter; Auflage: 2., vollst. neubearb. Aufl. p. 468. ISBN 3-11-015741-1.

- Institute for the German Language, Mannheim and University of Osnabrück, Institute for Linguistic and Literary Sciences.

- "Chronik des Boxer-Klub E.V. Sitz München". Boxer-Klub E.V. – Sitz München – Deutscher Boxerklub. Retrieved 2006-08-17.

- "Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy". Genetic Welfare Problems of Companion Animals. ufaw.org.uk: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- American Boxer Club. "Boxer Health Information". Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- American Boxer Club. "Genetic and Suspect Diseases in the Boxer". Archived from the original on 2006-09-15. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- Fred Lanting. "Spondylosis Deformans". Archived from the original on 2007-10-12.

- A survey of dystocia in the Boxer breed

- Mansfield, CS; et al. (2009). "Remission of histiocytic ulcerative colitis in Boxer dogs correlates with eradication of invasive intramucosal Escherichia coli". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 23 (5): 964–9. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0363.x. PMID 19678891.

- van der Beek S, Nielen AL, Schukken YH, Brascamp EW (1999). "Evaluation of genetic, common-litter, and within-litter effects on preweaning mortality in a birth cohort of puppies". Am. J. Vet. Res. 60 (9): 1106–10. PMID 10490080.

- "Mast Cell Tumour". Genetic Welfare Problems of Companion Animals. ufaw.org.uk: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "Summary results of the Purebred Dog Health Survey for Boxers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2011. Report from the Kennel Club/British Small Animal Veterinary Association Scientific Committee

- American Boxer Club. "Recommendations for Health Screening of Boxers in Breeding Programs". Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- Jennifer Walker, ABC Health & Research Committee. "Acepromazine and Boxers – References". Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- Wendy Wallner, DVM. "Warning on Acepromazine". Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- "How to Feed Your Boxer Dog". Boxer Fan Club. 2015-04-15.

- Case, L. P., Daristotle, L., Hayek, M. G., & Raasch, M. F. (2010). Canine and Feline Nutrition-E-Book: A Resource for Companion Animal Professionals. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Grandjean, D; Butterwick, R. (2009). Waltham pocket book of essential nutrition for cats and dogs. [Electronic Resource] Walthan-on-the-Wolds: Waltham Centre for Pet Nutrition.