Biting

Biting is a common behavior involving the opening and closing of the jaw. This behavior is found in reptiles, mammals, fish and amphibians. Arthropods can also bite. Biting can be a physical action in result of an attack, but it is also a normal activity or response in an animal as it eats, carries objects, softens and prepares food for its young, removes ectoparasites from its body surface, removes plant seeds attached to its fur or hair, scratching itself, and grooming other animals. Animal bites often result in serious infections and some times even death.[2] Dog bites are commonplace, with human children the most commonly bitten by dogs and the face being the most commonly bitten target.[3]

The muscle fibers in the jaw are responsible for the opening and closing of the mouth. They initially allow the organism to open their jaw, then contract to bring the teeth together, resulting in the action of a bite.[4] This behavior can have many implications and is exhibited by many different types of organisms, typically dangerous species such as spiders, snakes, and sharks. Biting is one of the main functions in an organism's life, providing the ability to forage, eat, build, play, protect and much more.

Types of teeth

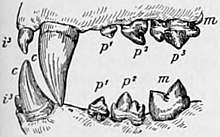

The types of teeth that organisms use to bite varies throughout the animal kingdom. Different types of teeth are seen in herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores as they are adapted over many years to better fit their diets. Carnivores possess canine, carnassial, and molar teeth, while herbivores are equipped with incisor teeth and wide-back molars.[5] In general, tooth shape has traditionally been used to predict dieting habits.[6] Carnivores have long, extremely sharp teeth for both gripping prey and cutting meat into chunks.[7] They lack flat chewing teeth because they swallow food in chunks. An example of this is shown by the broad, serrated teeth of great white sharks which prey on large marine animals.[8] On the other hand, herbivores have rows of wide, flat teeth to bite and chew grass and other plants. Cows spend up to eleven hours a day biting off grass and grinding it with their molars.[9] Omnivores consume both meat and plants, so they possess a mixture of flat teeth and sharp teeth.

Carrying mechanism

Biting can serve as a carrying mechanism for species such as beavers and ants, the raw power of their species-specific teeth allow them to carry large objects. In beavers specifically, they have a large tooth adapted for gnawing wood. Their jaw muscles are tuned to power through big trees and carry them back to their dam.[10] In ant behavior, ants use their powerful jaws to lift material back to the colony. They can carry several thousand times their weight due to their bite and adapted to use this to forage for their colonies.[11] Fire ants use their strong bite to get a grip on prey, and inject a toxin via its abdomen, then carry back to its territory.[12]

Dangerous bites

Some organisms have dangerous bites that produce toxin or venom. Many snakes carry a neurotoxic venom from one of the three major groups of toxins: postsynaptically active neurotoxins, presynaptically active neurotoxins, and myotoxic agents.[13] Spiders venom polypeptides target specific ion channels. This excites components of the peripheral, somatic, and autonomic nervous systems, causing hyperactivity of the channels and neurotransmitter release within the peripheral nervous system.[13] Spider bites or, arachnidism, are mainly a form of predation, but also means of protection. When trapped or accidentally tampered with by humans, spiders retaliate with biting.[14] The recluse spider and widow species have neurotoxins or necrotic agents that paralyze prey.[15]

There are several creatures with non-lethal bites that may cause discomfort, disease, or pain. Mosquito bites may cause sores that may last a few days; in some areas, they can spread diseases, such as West Nile fever via their bite.[16] Similarly, tick bites spread diseases endemic to their location. Most famously, Lyme disease can be spread by ticks, but ticks also serve as vectors for Colorado Tick Fever, African Tick Bite Fever, Tick-borne Encephalitis and the like.[17]

In humans

Biting is also an age appropriate behavior and reaction for human children 30 months and younger. Conversely, children above this age are expected to have verbal skills to explain their needs and dislikes, as biting is not seen as age appropriate. Biting may be prevented by methods including redirection, change in the environment and responding to biting by talking about appropriate ways to express anger and frustration. School-age children, those older than 30 months, who habitually bite may require professional intervention.[18] Some discussion of human biting appears in The Kinsey Report on Sexual Behavior in the Human Female.

Criminally, Forensic Dentistry is involved in bite-mark analysis. Because bite-marks change significantly over time, investigators must call for an expert as soon as possible. Bites are then analyzed to determine whether the biter was human, self-inflicted or not, and whether DNA was left behind from the biter. All measurements must be extremely precise, as small errors in measurement can lead to large errors in legal judgment.[19]

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2014-03-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cherry, James (2014). Feigin and Cherry's textbook of pediatric infectious diseases – Animal and Human Bites, Morven S. Edwards. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4557-1177-2; Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

- Kenneth M. Phillips (2009-12-27). "Dog Bite Statistics". Archived from the original on 2010-09-21. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- Ferrara, T.L.; Clausen, P.; Huber, D.R.; McHenry, C.R.; Peddemors, V.; Wroe, S. (2011). "Mechanics of biting in great white and sandtiger sharks". Journal of Biomechanics. 44 (3): 430–435. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.028. PMID 21129747.

- Animal Teeth | Types of Teeth | DK Find Out. (2018). Retrieved October 28, 2018, from https://www.dkfindout.com/us/animals-and-nature/food-chains/types-teeth/

- Sanson, Gordon (2016). "Cutting food in terrestrial carnivores and herbivores". Interface Focus. 6 (3): 20150109. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2015.0109. PMC 4843622. PMID 27274799.

- Animal Teeth | Types of Teeth | DK Find Out. (2018). Retrieved October 28, 2018, from https://www.dkfindout.com/us/animals-and-nature/food-chains/types-teeth/

- Ferrara, T.L.; Clausen, P.; Huber, D.R.; McHenry, C.R.; Peddemors, V.; Wroe, S. (2011). "Mechanics of biting in great white and sandtiger sharks". Journal of Biomechanics. 44 (3): 430–435. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.028. PMID 21129747.

- Wroe, S.; Huber, D. R.; Lowry, M.; McHenry, C.; Moreno, K.; Clausen, P.; Ferrara, T. L.; Cunningham, E.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: How hard can a great white bite?". Journal of Zoology. 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

- Müller-Schwarze, Dietland (2011). "Form, Weight, and Special Adaptations". The Beaver: Its Life and Impact. Cornell University Press. pp. 11–8. ISBN 978-0-8014-6086-9.

- Nguyen, Vienny; Lilly, Blaine; Castro, Carlos (2014). "The exoskeletal structure and tensile loading behavior of an ant neck joint". Journal of Biomechanics. 47 (2): 497–504. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.053. PMID 24287400. Lay summary – Entomology Today (February 11, 2014).

- Drees, Bastiaan M. (December 2002). "Medical Problems and Treatment Considerations for the Red Imported Fire Ant" (PDF). Texas A&M University.

- Harris, J. B.; Goonetilleke, A. (2004). "Animal poisons and the nervous system: What the neurologist needs to know". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 75: iii40–iii46. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.045724. PMC 1765666. PMID 15316044.

- "Workplace Safety & Health Topics Venomous Spiders". cdc.gov. February 24, 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2018

- Braitberg, G.; Segal, L. (2009). "Spider bites - Assessment and management". Australian Family Physician. 38 (11): 862–7. PMID 19893831. Archived from the original on 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "Mosquito Bites", Mayo Clinic, accessed June 28, 2019

- "Tickborne Diseases of the United States", The Center for Disease Control, accessed June 28, 2019

- Child Care Links,"How to Handle Biting Archived October 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine", retrieved 14 August 2007

- Shanna Freeman, "How Forensic Dentistry Works", How Stuff Works, accessed June 28, 2019

External links