Bouzes

Bouzes or Buzes (Greek: Βούζης, fl. 528–556) was an East Roman (Byzantine) general active in the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565) in the wars against the Sassanid Persians.

Buzes | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | Byzantine Empire |

| Rank | magister militum |

| Battles/wars | Iberian War, Lazic War |

| Relations | Vitalian (father), Coutzes and Venilus (brothers) John (cousin) |

Family

Bouzes was a native of Thrace. He was likely a son of the general and rebel Vitalian. Procopius identifies Coutzes and Venilus as brothers of Bouzes. An unnamed sister was mother to Domnentiolus.[1]

Iberian War

Battle of Thannuris (or Mindouos)

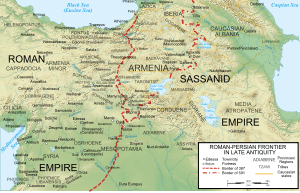

Bouzes is first mentioned in 528, as joint dux of Phoenice Libanensis together with his brother, Coutzes. (Their province was part of the wider Diocese of the East and contained areas to the east of Mount Lebanon). Bouzes was stationed at Palmyra, while Coutzes at Damascus. Both brothers are described as being young at the time by Procopius.[1]

Their first known mission sent the two brothers to the front lines of the Iberian War against the Sassanid Empire, reinforcing Belisarius at Mindouos.[1] Belisarius was attempting to construct a fortress at this location. "When the emperor (Justinian I) heard this, inasmuch as Belisarius was not able to beat off the Persians from the place with the army he had, he ordered another army to go thither, and also Coutzes and Bouzes, who at that time commanded the soldiers in Libanus. These two were brothers from Thrace, both young and inclined to be rash in engaging with the enemy. So both armies were gathered together and came in full force to the scene of the building operations, the Persians in order to hinder the work with all their power, and the Romans to defend the labourers. And a fierce battle took place in which the Romans were defeated, and there was a great slaughter of them, while some also were made captive by the enemy. Among these was Coutzes himself. All these captives the Persians led away to their own country, and, putting them in chains, confined them permanently in a cave; as for the fort, since no one defended it any longer, they razed what had been built to the ground." [2]

Battle of Dara

Bouzes survived the defeat. He is next mentioned taking part in the Battle of Dara (June, 530). He served in command of the cavalry alongside Pharas the Herulian. Among his attendants was Andreas, who distinguished himself in the first day of the battle.[1] "The extremity of the left straight trench which joined the cross trench, as far as the hill which rises here, was held by Bouzes with a large force of horsemen and by Pharas the Erulian with three hundred of his nation. On the right of these, outside the trench, at the angle formed by the cross trench and the straight section which extended from that point, were Sunicas and Aigan, Massagetae (Huns) by birth, with six hundred horsemen, in order that, if those under Bouzes and Pharas should be driven back, they might, by moving quickly on the flank, and getting in the rear of the enemy, be able easily to support the Romans at that point." [2]

"In the late afternoon a certain detachment of the horsemen who held the right wing [of the Sassanids], separating themselves from the rest of the army, came against the forces of Bouzes and Pharas. And the Romans retired a short distance to the rear. The Persians, however, did not pursue them, but remained there, fearing, I suppose, some move to surround them on the part of the enemy. Then the Romans who had turned to flight suddenly rushed upon them. And the Persians did not withstand their onset and rode back to the phalanx, and again the forces of Bouzes and Pharas stationed themselves in their own position. In this skirmish seven of the Persians fell, and the Romans gained possession of their bodies; thereafter both armies remained quietly in position." [2]

"But one Persian, a young man, riding up very close to the Roman army, began to challenge all of them, calling for whoever wished to do battle with him. And no one of the whole army dared face the danger, except a certain Andreas, one of the personal attendants of Bouzes, not a soldier nor one who had ever practised at all the business of war, but a trainer of youths in charge of a certain wrestling school in Byzantium. Through this it came about that he was following the army, for he cared for the person of Bouzes in the bath; his birthplace was Byzantium. This man alone had the courage, without being ordered by Bouzes or anyone else, to go out of his own accord to meet the man in single combat. And he caught the barbarian while still considering how he should deliver his attack, and hit him with his spear on the right breast. And the Persian did not bear the blow delivered by a man of such exceptional strength, and fell from his horse to the earth. Then Andreas with a small knife slew him like a sacrificial animal as he lay on his back, and a mighty shout was raised both from the city wall and from the Roman army." [2]

"But the Persians were deeply vexed at the outcome and sent forth another horseman for the same purpose, a manly fellow and well favoured as to bodily size, but not a youth, for some of the hair on his head already shewed grey. This horseman came up along the hostile army, and, brandishing vehemently the whip with which he was accustomed to strike his horse, he summoned to battle whoever among the Romans was willing. And when no one went out against him, Andreas, without attracting the notice of anyone, once more came forth, although he had been forbidden to do so by Hermogenes. So both rushed madly upon each other with their spears, and the weapons, driven against their corselets, were turned aside with mighty force, and the horses, striking together their heads, fell themselves and threw off their riders. And both the two men, falling very close to each other, made great haste to rise to their feet, but the Persian was not able to do this easily because his size was against him, while Andreas, anticipating him (for his practice in the wrestling school gave him this advantage), smote him as he was rising on his knee, and as he fell again to the ground dispatched him. Then a roar went up from the wall and from the Roman army as great, if not greater, than before; and the Persians broke their phalanx and withdrew to Ammodios, while the Romans, raising the paean, went inside the fortifications; for already it was growing dark. Thus both armies passed that night." [2]

Siege of Martyropolis

In 531, Bouzes was unable to participate at the Battle of Callinicum (19 April, 531). He was reportedly stationed at Amida, an illness preventing him from campaigning. Zacharias Rhetor mentions that Bouzes tasked his nephew Domnentiolus with leading an army to Abhgarsat. This location is only mentioned by Zacharias.[1] The Byzantine forces faced the Sassanid army and were defeated. Domnentiolus himself was captured by his enemies and transported to the interior of the Sassanid Empire. In 532, the Eternal Peace was concluded between the two powers. Domnentiolus was released "in an exchange of prisoners"[3]

In September/October 531, Bouzes and Bessas were joint commanders of the garrison at Martyropolis. The city was besieged by a strong Sassanid force. The death of Kavadh I resulted in the premature end of the siege.[1] Procopius details: "And the Persians once more invaded Mesopotamia with a great army under command of Chanaranges and Aspebedes and Mermeroes. Since no one dared to engage with them, they made camp and began the siege of Martyropolis, where Bouzes and Bessas had been stationed in command of the garrison. This city lies in the land called Sophanene, two hundred and forty stades distant from the city of Amida toward the north; it is just on the River Nymphius which divides the land of the Romans and the Persians. So the Persians began to assail the fortifications, and, while the besieged at first withstood them manfully, it did not seem likely that they would hold out long. For the circuit-wall was quite easily assailable in most parts, and could be captured very easily by a Persian siege, and besides they did not have a sufficient supply of provisions, nor indeed had they engines of war nor anything else that was of any value for defending themselves." [4]

"Thus then Chosroes secured the power. But at Martyropolis, Sittas and Hermogenes were in fear concerning the city, since they were utterly unable to defend it in its peril, and they sent certain men to the enemy, who came before the generals and spoke as follows: "It has escaped your own notice that you are becoming wrongfully an obstacle to the king of the Persians and to the blessings of peace and to each state. For ambassadors sent from the emperor are even now present in order that they may go to the king of the Persians and there settle the differences and establish a treaty with him; but do you as quickly as possible remove from the land of the Romans and permit the ambassadors to act in the manner which will be of advantage to both peoples. For we are ready also to give as hostages men of repute concerning these very things, to prove that they will be actually accomplished at no distant date." Such were the words of the ambassadors of the Romans. It happened also that a messenger came to them from the palace, who brought them word that Cabades had died and that Chosroes, son of Cabades, had become king over the Persians, and that in this way the situation had become unsettled. And as a result of this the generals heard the words of the Romans gladly, since they feared also the attack of the Huns. The Romans therefore straightway gave as hostages Martinus and one of the body-guards of Sittas, Senecius by name; so the Persians broke up the siege and made their departure promptly.[4]

Armenian revolt

Bouzes resurfaces in 539, when he succeeded the deceased Sittas in command of Roman Armenia. He was tasked with ending an ongoing Armenian revolt. His efforts included the assassination of John, a descendant of the Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia. John was survived by his son Artabanes.[1] "After the death of Sittas the emperor commanded Bouzes to go against the Armenians; and he, upon drawing near, sent to them promising to effect a reconciliation between the emperor and all the Armenians, and asking that some of their notables should come to confer with him on these matters. Now the Armenians as a whole were unable to trust Bouzes, nor were they willing to receive his proposals. But there was a certain man of the Arsacidae who was especially friendly with him, John by name, the father of Artabanes, and this man, trusting in Bouzes as his friend, came to him with his son-in-law, Bassaces, and a few others; but when these men had reached the spot where they were to meet Bouzes on the following day, and had made their bivouac there, they perceived that they had come into a place surrounded by the Roman army. Bassaces, the son-in-law, therefore earnestly entreated John to fly. And since he was not able to persuade him, he left him there alone, and in company with all the others eluded the Romans, and went back again by the same road. And Bouzes found John alone and slew him; and since after this the Armenians had no hope of ever reaching an agreement with the Romans, and since they were unable to prevail over the emperor in war, they came before the Persian king led by Bassaces, an energetic man." The events led to a new conflict between the Byzantine and Sassanid Empires.[5]

In 540, Justinian I appointed Belisarius and Bouzes joint magistri militum per Orientem. Bouzes would personally command the area between the Euphrates and the Persian border. He also temporarily held command over Belisarius' areas. Belisarius had just been recalled from the Gothic War and was still in the Italian Peninsula. He would not reach his new post until the spring of 541.[1] "The emperor had divided into two parts the military command of the East, leaving the portion as far as the River Euphrates under the control of Belisarius who formerly held the command of the whole, while the portion from there as far as the Persian boundary he entrusted to Bouzes, commanding him to take charge of the whole territory of the East until Belisarius should return from Italy." [6]

In the spring of the same year (540), the Sassanids invaded Byzantine areas. They avoided the fortresses of Mesopotamia, heading for the easier targets of Syria and Cilicia. Bouzes was stationed at Hierapolis at the beginning of this campaign season. By mid-summer, the Sassanids had captured Sura. Bouzes left Hierapolis at the head of his best troops. He promised to return if the city came under Persian threat, but Procopius accuses Bouzes of simply vanishing, with neither the Hierapolitans or the Sassanids able to locate him.[1][7] "Bouzes therefore at first remained at Hierapolis, keeping his whole army with him; but when he learned what had befallen Sura, he called together the first men of the Hierapolitans and spoke as follows: "Whenever men are confronted with a struggle against an assailant with whom they are evenly matched in strength, it is not at all unreasonable that they should engage in open conflict with the enemy; but for those who are by comparison much inferior to their opponents it will be more advantageous to circumvent their enemy by some kind of tricks than to array themselves openly against them and thus enter into foreseen danger. How great, now, the army of Chosroes is, you are assuredly informed. And if, with this army, he wishes to capture us by siege, and if we carry on the fight from the wall, it is probable that, while our supplies will fail us, the Persians will secure all they need from our land, where there will be no one to oppose them. And if the siege is prolonged in this way, I believe too that the fortification wall will not withstand the assaults of the enemy, for in many places it is most susceptible to attack, and thus irreparable harm will come to the Romans. But if with a portion of the army we guard the wall of the city, while the rest of us occupy the heights about the city, we shall make attacks from there at times upon the camp of our antagonists, and at times upon those who are sent out for the sake of provisions, and thus compel Chosroes to abandon the siege immediately and to make his retreat within a short time; for he will not be at all able to direct his attack without fear against the fortifications, nor to provide any of the necessities for so great an army." So spoke Bouzes; and in his words he seemed to set forth the advantageous course of action, but of what was necessary he did nothing. For he chose out all that portion of the Roman army which was of marked excellence and was off. And where in the world he was, neither any of the Romans in Hierapolis, nor the hostile army was able to learn." [6]

He is mentioned again later that year at Edessa. The local citizens were attempting to pay ransom for the safe return of prisoners held at Antioch. Bouzes prevented them from doing so.[1] "Chosroes ...wished to sell off all the captives from Antioch. And when the citizens of Edessa learned of this, they displayed an unheard-of zeal. For there was not a person who did not bring ransom for the captives and deposit it in the sanctuary according to the measure of his possessions. And there were some who even exceeded their proportionate amount in so doing. For the harlots took off all the adornment which they wore on their persons, and threw it down there, and any farmer who was in want of plate or of money, but who had an ass or a sheep, brought this to the sanctuary with great zeal. So there was collected an exceedingly great amount of gold and silver and money in other forms, but not a bit of it was given for ransom. For Bouzes happened to be present there, and he took in hand to prevent the transaction, expecting that this would bring him some great gain. Therefore Chosroes moved forward, taking with him all the captives." [8]

Lazic War

The hostilities of 540 gave way to the long-running Lazic War (541-562). In 541, Bouzes is recorded as one of the various Roman (Byzantine) commanders gathering at Dara to decide on a course of action. He was among those in favor of an invasion into Sassanid areas.[1] Procopius mentions: "At this time Belisarius had arrived in Mesopotamia and was gathering his army from every quarter, and he also kept sending men into the land of Persia to act as spies. And wishing himself to encounter the enemy there, if they should again make an incursion into the land of the Romans, he was organizing on the spot and equipping the soldiers, who were for the most part without either arms or armour, and in terror of the name of the Persians. Now the spies returned and declared that for the present there would be no invasion of the enemy; for Chosroes was occupied elsewhere with a war against the Huns. And Belisarius, upon learning this, wished to invade the land of the enemy immediately with his whole army. ... And Peter and Bouzes urged him to lead the army without any hesitation against the enemy's country. And their opinion was followed immediately by the whole council. " [9]

While Bouzes probably served under Belisarius in this campaign, his specific activities are not mentioned. The Byzantine invasion force failed to capture Nisibis, though they did capture Sisauranon. In the campaign season of 542, Khosrau I once again invaded Byzantine-held areas. Bouzes, Justus and others retreated within the walls of Hierapolis. He was one of the co-writers of a letter asking Belisarius to join them there. Belisarius instead moved towards Europum, summoning the other leaders there.[1] Procopius narrates: "At the opening of spring Chosroes, the son of Cabades, for the third time began an invasion into the land of the Romans with a mighty army, keeping the River Euphrates on the right. ... The Emperor Justinian, upon learning of the inroad of the Persians, again sent Belisarius against them. And he came with great speed to Euphratesia since he had no army with him, riding on the government post-horses, which they are accustomed to call "veredi," while Justus, the nephew of the emperor, together with Bouzes and certain others, was in Hierapolis where he had fled for refuge." [10]

"And when these men heard that Belisarius was coming and was not far away, they wrote a letter to him which ran as follows: "Once more Chosroes, as you yourself doubtless know, has taken the field against the Romans, bringing a much greater army than formerly; and where he is purposing to go is not yet evident, except indeed that we hear he is very near, and that he has injured no place, but is always moving ahead. But come to us as quickly as possible, if indeed you are able to escape detection by the army of the enemy, in order that you yourself may be safe for the emperor, and that you may join us in guarding Hierapolis." Such was the message of the letter. But Belisarius, not approving the advice given, came to the place called Europum, which is on the River Euphrates. From there he sent about in all directions and began to gather his army, and there he established his camp; and the officers in Hierapolis he answered with the following words: "If, now, Chosroes is proceeding against any other peoples, and not against subjects of the Romans, this plan of yours is well considered and insures the greatest possible degree of safety; for it is great folly for those who have the opportunity of remaining quiet and being rid of trouble to enter into any unnecessary danger; but if, immediately after departing from here, this barbarian is going to fall upon some other territory of the Emperor Justinian, and that an exceptionally good one, but without any guard of soldiers, be assured that to perish valorously is better in every way than to be saved without a fight. For this would justly be called not salvation but treason. But come as quickly as possible to Europum, where, after collecting the whole army, I hope to deal with the enemy as God permits." And when the officers saw this message, they took courage, and leaving there Justus with some few men in order to guard Hierapolis, all the others with the rest of the army came to Europum." [10]

Falling out of favor

In the Summer of 542, Constantinople was affected by the so-called Plague of Justinian. The emperor Justinian himself caught the plague and there were discussions of an imminent succession. Belisarius and Bouzes, both absent in campaign, reportedly swore to oppose any emperor chosen without their consent. Theodora took offense and had them both recalled at Constantinople to face her judgement. Bouzes was captured upon his return. He reportedly spent two years and four months (late 542-early 545) held in an underground chamber, located below the women's quarters of the palace. While eventually released, Procopius suggests that Bouzes continued to suffer from a failing eyesight and ill health for the rest of his life.[1]

Procopius narrates: "The plague which I mentioned in the previous narrative was ravaging the population of Byzantium. And the Emperor Justinian was taken very seriously ill, so that it was even reported that he had died. And this report was circulated by rumour and was carried as far as the Roman army. There some of the commanders began to say that, if the Romans should set up a second Justinian as Emperor over them in Byzantium, they would never tolerate it. But a little later it so fell out that the Emperor recovered, and the commanders of the Roman army began to slander one another. For Peter the General and John whom they called the Glutton declared that they had heard Belisarius and Bouzes say those things which I have just mentioned. The Empress Theodora, declaring that these slighting things which the men had said were directed against her, became quite out of patience. So she straightway summoned them all to Byzantium and made an investigation of the report."[11]

"She [Theodora] called Bouzes suddenly into the woman's apartment as if to communicate to him something very important. Now there was a suite of rooms in the Palace, below the ground level, secure and a veritable labyrinth, so that it seemed to resemble Tartarus, where she usually kept in confinement those who had given offence. So Bouzes was hurled into this pit, and in that place he, a man sprung from a line of consuls, remained, forever unaware of time. For as he sat there in the darkness, he could [not] distinguish whether it was day or night, nor could he communicate with any other person. For the man who threw him his food for each day met him in silence, one as dumb as the other, as one beast meets another. And straightway it was supposed by all that he had died, but no one dared mention or recall him. But two years and four months later she was moved to pity and released the man, and he was seen by all as one who had returned from the dead. But thereafter he always suffered from weak sight and his whole body was sickly."[11]

"Such was the experience of Bouzes. As for Belisarius, though he was convicted of none of the charges, the Emperor, at the insistence of the Empress, relieved him of the command which he held and appointed Martinus to be General of the East in his stead, and instructed him to distribute the spearmen and guards of Belisarius and all his servants who were notable men in war to certain of the officers and Palace eunuchs. So these cast lots for them and divided them all up among themselves, arms and all, as each happened to win them. And many of those who had been his friends or had previously served him in some way he forbade to visit Belisarius any longer. And he went about, a sorry and incredible sight, Belisarius a private citizen in Byzantium, practically alone, always pensive and gloomy, and dreading a death by violence." [11]

Later years

In either the late summer or early autumn of 548, Germanus confided to Bouzes and Constantianus about the ongoing conspiracy of Artabanes, a plot to assassinate Justinian. While Justinian had the conspirators arrested, Germanus and his sons also came under suspicion for their contact. In particular, they had to explain why they alerted generals loyal to Justinian but failed to inform the emperor himself. Bouzes, Constantianus, Marcellus and Leontius testified under oath to the innocence of Germanus.[1][12]

In spring 549, Bouzes was once again active on campaign. He led (along with Aratius, Constantianus, and John) an army of 10,000 cavalry men. They were sent to assist the Lombards against the Gepids. This campaign was short-lived as the two opponents concluded a peace treaty, making the presence of Byzantine forces unnecessary. This is the last time Bouzes is mentioned by Procopius.[1]

He is next mentioned by Agathias c. 554-556 as one of the generals in charge of the army in Lazica. In 554, Bessas was the chief commander in this area. Martin, magister militum per Armeniam, seems to have been the second-in-command. Justin served as a deputy to Martinus and was apparently third in line. Leaving Bouzes as fourth in the chain of command. Agathias reports that all four men were veterans of previous wars.[1][13][14]

Bessas was dismissed from office in 554/555, leaving Martin as the chief commander. Bouzes is explicitly said to be third-in-command. In September/October, 555 the three of them and the sacellarius Rusticus went to meet Gubazes II of Lazica. Justin and Bouzes reportedly thought that they were to discuss a planned attack on the Sassanid forces in Onoguris (a local fort). Martin and Rusticus had Gubazes murdered, reportedly shocking Bouzes. However, he soon suspected that Justinian himself had ordered the assassination. He thus held his tongue from too much protesting.[1]

Preparations for an attack at Onoguris continued, but Sassanid reinforcements started arriving. Bouzes suggested that they should deal with the new arrivals first, postponing the planned attack. He was overruled. The Byzantines lost the battle of Onoguris. Bouzes is credited with successfully guarding a bridge crossing, during the subsequent retreat. His efforts saved the lives of many soldiers who crossed the bridge to safety.[1]

In early 556, Bouzes was ordered to defend Nesus (a minor island) at the River Phasis. He was later joined there by Justin. The two continued guarding the island, while the rest of the army was campaigning against the Misimiani (a local tribe). He is not mentioned again.[1]

References

- Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), p. 254-257 and Lillington-Martin (2012), p 4-5 and 2010.

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 1, Chapter 13 (cf. Lillington-Martin, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2013).

- Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), p. 413

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 1, Chapter 21

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapter 3

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapter 6

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapters 5-6

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapter 13

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapter 16

- Procopius, History of the Wars, Book 2, Chapter 20

- Procopius, Secret History, Book 2, Chapter 4

- Bury (1958), p. 68

- Greatrex & Lieu (2002), pp. 120, 122

- Evans (1996), p. 168

Sources

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958), History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-20399-7

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002), The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-14687-6

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher:

- 2006, “Pilot Field-Walking Survey near Ambar & Dara, SE Turkey”, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara: Travel Grant Report, Bulletin of British Byzantine Studies, 32 (2006), p 40-45.

- 2007, “Archaeological and Ancient Literary Evidence for a Battle near Dara Gap, Turkey, AD 530: Topography, Texts and Trenches” in: BAR –S1717, 2007 The Late Roman Army in the Near East from Diocletian to the Arab Conquest Proceedings of a colloquium held at Potenza, Acerenza and Matera, Italy edited by Ariel S. Lewin and Pietrina Pellegrini, p 299-311.

- 2008, “Roman tactics defeat Persian pride” in Ancient Warfare edited by Jasper Oorthuys, Vol. II, Issue 1 (February 2008), pages 36–40.

- 2010, “Source for a handbook: Reflections of the Wars in the Strategikon and archaeology” in: Ancient Warfare edited by Jasper Oorthuys, Vol. IV, Issue 3 (June 2010), pages 33–37.

- 2012, “Hard and Soft Power on the Eastern Frontier: a Roman Fortlet between Dara and Nisibis, Mesopotamia, Turkey, Prokopios’ Mindouos?” in: The Byzantinist, edited by Douglas Whalin, Issue 2 (2012), pages 4-5.

- 2013, “Procopius on the struggle for Dara and Rome” in: War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives (Late Antique Archaeology 8.1-8.2 2010-11) by Sarantis A. and Christie N. (2010–11) edd. (Brill, Leiden 2013), pages 599-630, ISBN 978-90-04-25257-8.

- Martindale, John R.; Jones, A.H.M.; Morris, John (1992), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire - Volume III, AD 527–641, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20160-8

- Procopius of Caesarea; Dewing, Henry Bronson (1914), History of the wars. vol. 1, Books I-II, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-99054-8

- Procopius of Caesarea; Dewing, Henry Bronson (1935), Secret History, Cambridge University Press