Hermogenes (magister officiorum)

Hermogenes (Greek: Ἑρμογένης, died 535/536) was an East Roman (Byzantine) official who served as magister officiorum, military commander and diplomatic envoy during the Iberian War against Sassanid Persia in the early reign of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565).

Biography

Hermogenes was probably from Scythia Minor (modern Dobrudja), as he is called "the Scythian" in Byzantine chronicles. In the 510s, he served as an assessor (head legal assistant) to the general Vitalian, who in 513–515 led a series of revolts against Emperor Anastasius I (r. 491–518).[1]

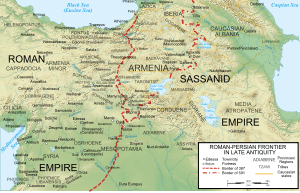

By May 529, he had risen to the post of magister officiorum, head of the imperial secretariat. In April 529, he was sent as an envoy with many gifts to the Persian shah Kavadh I (r. 488–531) to formally announce Justinian's accession to the Byzantine throne and propose peace in the ongoing war. He arrived before Kavadh in July and returned bearing his reply for a one-year truce.[1][2] In response, Emperor Justinian sent him again as an envoy, along with Rufinus, who had led repeated embassies to the Persian court in the past. The two arrived at Antioch in March 530, and then set out for Hierapolis, from where they sent notice of their arrival to Kavadh, expecting negotiations to resume. Kavadh, however, had prepared an invasion army and postponed meeting them. While Rufinus remained at Hierapolis, Hermogenes joined the Byzantine army commanded by Belisarius, newly promoted to magister militum per Orientem, at the fortress of Dara on the Persian border.[3][4]

As Hermogenes had been instructed by Emperor Justinian to aid Belisarius in forming his army, he came to share command of the Byzantine forces with the latter. When the Persian army under Mihran advanced across the border to Ammodius (June 530), the Byzantines too exited Dara, arraying their forces in front of the city. Belisarius and Hermogenes attempted to resume negotiations the day before the battle, but the Persian commander refused. Hermogenes shared command with Belisarius during the subsequent Battle of Dara, which ended in a major Byzantine victory.[5] After the battle, Kavadh accepted a new embassy, but without Hermogenes, who returned to Constantinople in late 530 or early 531. In the meantime, Kavadh had sent Rufinus back to Emperor Justinian with terms acceptable to the latter. When Rufinus returned to the shah bearing Justinian's agreement, the Persian ruler had changed his mind and resolved to renew the war.[3][6]

In spring 531, as news arrived of another Persian invasion, Hermogenes was sent again to the East at the head of reinforcements for Belisarius's army. He joined Belisarius, who had been following the Persians, at Barbalissus. There, Hermogenes mediated and resolved a dispute between Belisarius and one of his subordinate commanders, Sunicas. At this point the Persians, confronted by the Byzantine army, decided to withdraw. Hermogenes agreed with Belisarius's opinion that, their invasion having failed, they should be allowed to do so, but his subordinate commanders advocated battle. The two armies met near Callinicum, but the ensuing battle resulted in a heavy Byzantine defeat.[3][7] In the aftermath of the battle, Hermogenes visited Kavadh as an envoy, but failed to achieve any results. He returned to Constantinople, from where he was again sent as an envoy in late summer of 531. There, he attached himself to the army of Sittas, and was with Sittas when he relieved the city of Martyropolis from a Persian siege.[8]

Whilst at the city, news arrived of Kavadh's death and the succession of his son, Khosrau I (r. 531–579). Khosrau wrote to Emperor Justinian through Hermogenes for a renewal of talks, but the Byzantine emperor forbade his envoys, Rufinus and Strategius, who were waiting at Edessa, to do so. If Emperor Justinian thus hoped to destabilize Khosrau's position, his hopes were thwarted: the new shah quickly suppressed the threat posed by his brother and the Mazdakites, and renewed his offer of negotiations, along with a three-month truce.[9][10] Emperor Justinian instructed Hermogenes to accept the truce, and after an exchange of hostages, the Persian army withdrew from Byzantine territory. Hermogenes was then one of the four Byzantine envoys sent to negotiate with Khosrau himself. The talks broke down, but a renewed embassy by Hermogenes and Rufinus succeeded in concluding the so-called "Eternal Peace" in September 532.[9][11]

Hermogenes was dismissed as magister officiorum after November 533, being replaced by Tribonian. He held the post again in 535, shortly before his death, which occurred sometime before March 18, 536.[12] Hermogenes had a son, Saturninus. Sometime after Hermogenes's death, he tried to marry his cousin, the daughter of Cyril, commander of the foederati under Belisarius, but this was thwarted by the Empress Theodora. Instead, the empress had him marry the daughter of a former courtesan living in the palace, and when he protested, he was flogged.[13]

References

- Martindale 1992, p. 590.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 87–88.

- Martindale 1992, p. 591.

- Martindale 1980, pp. 954–955; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 88.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 184–185, 591; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 88–90.

- Martindale 1980, p. 955; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 90–91.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 92–93.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 591–592.

- Martindale 1992, p. 592.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 96.

- Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 591, 593.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 371–372, 1115.

Sources

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume II, AD 395–527. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20159-4.

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume III, AD 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.