Bombus occidentalis

Bombus occidentalis, the western bumblebee, is one of around 30 bumblebee species present in the western United States and western Canada.[1] A recent review of all of its close relatives worldwide appears to have confirmed its status as a separate species.[2]

| Bombus occidentalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Bombus |

| Subgenus: | Bombus |

| Species: | B. occidentalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Bombus occidentalis (Greene, 1858) | |

| |

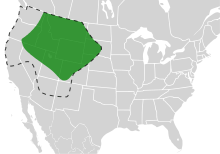

| The range of Bombus occidentalis. (Dashed line indicates former range within the United States (not Canada).) | |

Description

Western bumblebee workers have three main color variations.[3] The first color variation is found from northern California, north to British Columbia, and east to southwest Saskatchewan and Montana.[3] B. occidentalis in these areas have yellow hair on front part of thorax. They are also marked by black hair segments on the basal section of the fourth abdominal segments have black hair and whitish lower edge of the fourth and fifth abdominal segments. In addition, they also have sparse whitish hairs that may appear black on the sixth abdominal segment, and an entirely black head.

The second color variation is found along the central coast in California.[3] It has yellow hair on the sides of the second abdominal segment and all of the third abdominal segment and a reddish-brown hair on fifth abdominal segment.

The third color variation is found from the Rocky Mountains to Alaska.[3] It has yellow hair on the thorax behind the wings and on the rear of the second and all of the third abdominal segments.

Identification

All insects have three main body parts; the head, thorax, and abdomen.[3] Bumblebee species identification tends to refer to colorations on the abdominal segments. The abdominal segments are numbered from T1 to T6 (T7 if male) starting from the abdominal segment closest to the thorax and then working ventrally.

Sex determination

A few ways are used to determine the sex of the western bumblebee.[1] The males (drones) have seven abdominal segments, while the females (queens and workers) have only six.[1] The drones' antennae have 13 segments, while the females have only 12.[1] Drones have no stingers. Additionally, the hind legs of the females tend to be wider and fatter with a pollen basket often visible.[1] Drones have thinner hind legs that do not have pollen baskets.[1] Another clue to sexual identity among B. occidentalis species is when they are being observed. Queens are the first to appear in the spring and then the workers appear after. All females can then be seen throughout the summer and into early fall. The drones only appear in the late summer and early fall.

Taxonomy and Phylogeny

.jpg)

This species is of class Insecta, order Hymenoptera, and family Apidae. Although closely related to Bombus terricola, DNA evidence supports that they are a distinct species. Evidence of a subspecies divide is found through examination of the COI-barcode of the bees, suggesting that Bombus occidentalis can be divided between the northern and southern population. The supposed subspecies each have specific haplotype groups, which is reflected by the differences in hair length between the populations. The southern B. occidentalis seem to have notably shorter hair compared to the northern B. occidentalis.[4]

Distribution and Population

Bombus occidentalis was once one of the most common bee species in the North West America.[4] They have been found from the Mediterranean California all the way up to the Tundra regions of Alaska, making them one of the bees with the widest range geographic range.[4] However, recently there has been a noticeable decline in population.[5] In the past decade, the population of B. occidentalis has dropped by around 40.32%. The disappearance of these bees have been especially significant in California, western Oregon, and western Washington.[4] The range and persistence of B. occidentalis has also gone down by around 20%. Some scientists point to the rise of Nosema, a parasite, as the reason for the decline in population. Others say that the population decline could have come because of the invasion of European honey bees.[6] A recent study in 2016 suggests that the Western bumblebee population is rebounding, possibly due to evolutionary development of resistance to Nosema.[7]

Roles

Like most bumble bees, B. occidentalis colonies are made up of one queen, some female workers, and other reproductive members of the colony when the end of a season is near.[4] The queen's job, after the start of the colony is to lay eggs. Bumble bee workers remain with the queen and help with the production of additional workers and male and female reproductive members. It is their job to feed the larvae. The female workers also have other roles such as foraging for nectar and pollen and defending the colony against predators and parasites.[4]

Only the female reproductive members, otherwise known as the gynes, survive the winter so that they can go through the colony cycle once again. Gynes have the potential to become queens, and it is their responsibility to find a space for hibernation during the winter so that they can start a colony again next season.[4]

Colony Cycle

A new colony typically starts in the early spring by a solitary queen. First, the queen finds a suitable nest site. Like other bumble bees, B. occidentalis nests underground in cavities or random burrows left behind by rodents or other animals. The queen must then construct a wax structure and collect pollen to create a mass to lay eggs on.[4]

When the first brood of female workers have become adults, they take over the jobs of foraging for nectar and pollen, defending the colony, and feeding larvae. The queen's only job at this stage is to lay more eggs. A colony of B. occidentalis can have up to around 1,600 workers, which is large compared to that of other bumble bee species.[4] From early February to late November, the colony enters a flight period. Then, around the beginning of the fall, the reproductive individuals of the colony are produced. When winter starts, the old queen, workers, and males all die, leaving the gynes to search for a site to spend the winter hibernating.[4]

Behavior

Western bumblebees are generalist foragers.[8] Because they do not depend on any one flower type, they are considered to be excellent pollinators. Bumblebees are also able to fly in cooler temperatures and lower flight levels than many other bees.[9] Additionally, bumblebees perform "buzz pollination". This behavior is displayed when a bumblebee grabs the pollen-producing structure of the flower in her jaws and vibrates her wing musculature, causing vibrations that dislodge pollen that would have otherwise remained trapped in the flower's anthers.[9] Tomatoes, peppers, and cranberries are some of the plants that require this type of pollination.[8] For these reasons, bumblebees are considered to be more effective pollinators than honey bees. Bombus occidentalis has been commercially reared to pollinate crops such as alfalfa, avocados, apples, cherries, blackberries, cranberries, and blueberries.[9]

Workers collect nectar and regurgitate it in the nest. Pollen is collected and put into "pollen baskets" located on the hind legs. Nectar provides carbohydrates while pollen provides protein.

.jpg)

Foraging Behavior

B. occidentalis are social bees, and successful foragers returning to the nest can stimulate their nestmates to forage,[10] although presumably like other bumblebees, they cannot communicate the actual location of resources.[11] This phenomenon is often referred to as 'foraging activation'. The amount of recruitment a returning forager is able to garner depends on the quality (i.e. concentration) of the nectar (or sucrose) that it has found.[10] The mechanism by which foraging activation occurs is not well understood, but it is possible that the returning forager, which before unloading its cargo will spend some time running around the nest and interacting with its nestmates,[11] releases a pheromone that induces foraging behaviour.[12] Furthermore, the sudden influx of high-quality nectar may itself stimulate foraging behaviour.[12]

Although bumblebees cannot apparently communicate resource location, it appears that foraging activation can communicate which floral species was particularly rewarding through scent, as the activated nestmates show preference for the odour brought home by the returning forager.[11]

Nectar Robbing Behavior

The "nectar robbing" behavior is exhibited when the organism obtains the nectar of the flowers without getting in contact with sexual parts of the flowers. B. occidentalis can be seen displaying this behavior due to the shortness of their tongues. Instead of going through the normal route, B. occidentalis use their mandibles to make holes to circumvent the process. The mandibles of B. occidentalis are thus understandably more toothed than that of other bumble species to help them cut into the flowers.[13]

Importance of Nectar

It is crucial for B. occidentalis to maintain high levels of nectar for their colony. Not only does the level of stored nectar affect the temperature of the colony, but deficiencies in nectar cause a significant change in behavior due to low energy of the bees. When energy abundant colonies are threatened by predators, they assume the natural defense behavior, moving about loudly to deter the predator. However, low energy colonies will remain still in their colonies. Although temporary low energy periods do not affect the survivability of the larvae, it increases the colonies' susceptibility to predators and increases the time of development for the larvae.[14]

Brood Recognition of Queens

The queens of B. occidentalis have the ability to recognize her own nest and brood. Upon arriving on a specific brood, the queen will behave differently depending on whether it is her own brood or foreign. Queens will spend significantly more time inspecting the surface of foreign brood clumps with their antennas if they are on a foreign brood. Upon recognizing the brood as not their own, the Queens will be more much likely to depart during this observation period. However, these queens will stay within the vicinity of the foreign brood, making short flights around the entrance of the nest before reentering it. Most queens will choose to adopt the new colony rather than to abandon it, and the workers of the foreign brood will start working for the new queen. In contrast, queens that return to their original nests will incubate their brood and lather honey pot on its brood much more quickly.[15]

Some scientists hypothesize that this ability could have come about as an evolutionary response to usurpation and parasitism. B. occidentalis suffer high rates of inter-specific and intra-specific usurpation. In addition, they also face invasion by the parasitic Psithyrus bees. It is possible that the recognition ability evolved in form of adaptions to them. Others argue that brood recognition ability is a byproduct of factors of B. occidentalis. For social wasps, like B. occidentalis, nestmate recognition is crucial. The queen might have just evolved to recognize unfamiliar odors, allowing them to also recognize foreign broods.[15]

Threats

Threats to this species include:[8]

- Spread of pests and diseases by the commercial bumblebee industry

- Other pests and diseases[8]

- Habitat destruction or alteration that may degrade, destroy, alter, fragment, and reduce their food supply or nest sites

- Pesticides and insecticides (ground bumblebees are particularly susceptible)

- Invasive plant species that may directly compete with native nectar and pollen plants

- Natural pest or predator population cycles[8]

Conservation

Due to their role as pollinators, loss of bumblebee populations can have far-ranging ecological impacts.[8] B. occidentalis once had a wide range that included northern California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, Idaho, Montana, western Nebraska, western North Dakota, western South Dakota, Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, northern Arizona, and New Mexico.[8] Since 1998, it has been declining in population.[3] The areas of greatest decline have been reported in western and central California, western Oregon, western Washington, and British Columbia. From southern British Columbia to central California, the species has nearly disappeared.[3] However, the historic range was never systematically sampled.[3]

Agricultural and urban development has resulted in bumblebee habitat becoming increasingly fragmented.[8] All bumblebee species have small effective population sizes due to their breeding system, and are particularly vulnerable to inbreeding which reduces the genetic diversity within a population,[8] and theoretically can increase the risk of population decline.[8]

Between 1992 and 1994, B. occidentalis and B. impatiens were commercially reared for crop pollination, shipped to European rearing facilities and then shipped back.[3] Bumblebee expert Dr. Robbin Thorp has hypothesized that their decline is in part due to a disease acquired from a European bee while being reared in the same facility.[3] North American bumblebees would have had no prior resistance to this pathogen. Upon returning to North America, affected bumblebees interacted and spread the disease to wild populations.[3] B. occidentalis and B. franklini were affected in the western United States.[8] B. affinis and B. terricola were affected in the eastern United States.[8] All four species' populations have been declining since the 1990s. Additionally, these four bumblebee species are closely related and belong to the same subgenus; Bombus sensu stricto.[8] Dr. Thorp has also hypothesized that B. impatiens species may have been the carrier and that different bumblebee species may differ in their pathogen sensitivity.[8] In 2007, the National Research Council determined that the major cause of decline in native bumblebees appeared to be recently introduced non-native fungal and protozoan parasites, including Nosema bombi and Crithidia bombi.[8]

Human Importance

As mentioned before, B. occidentalis has been previously used to help in greenhouses. They have been used for a variety of crops, but have played an especially important role with tomatoes.[4] A problem with the use of these bumble bees was the drifting effect. Due to the close aggregation of colonies within the greenhouse habitats, they found that some bees developed a behavior of drifting into foreign colonies. These drifting bees were essentially social parasites, as they give up their roles in their colonies and introduce their mature ovaries to foreign colonies.[16]

Furthermore, due to careless regulation between states in America and Europe, Nosema parasitism became prevalent within the B. occidentalis population. Now they are no longer bred or sold commercially because of the threateningly low number, and B. impatiens have been used in their place.[6]

References

- Pocket Guide to Identifying The Western Bumble Bee Bombus occidentalis. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- P. H. Williams; et al. (2012). "Unveiling cryptic species of the bumblebee subgenus Bombus s. str. world-wide with COI barcodes" (PDF). Systematics and Biodiversity. 10: 21–56. doi:10.1080/14772000.2012.664574. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- Bumble bees: western bumble bee (Bombus occidentalis). Archived 2010-01-23 at the Wayback Machine The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Hatfield, R., et al. 2015. Bombus occidentalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 09 March 2016.

- Colla, S. R.; Ratti, C. M. (2010). "Evidence for the decline of the western bumble bee (Bombus occidentalis Greene) in British Columbia" (PDF). Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 86 (2): 32–34. doi:10.3956/2009-22.1.

- Sikes, D.; et al. (2015-01-01). "Bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus spp.) of Interior Alaska: Species composition, distribution, seasonal biology, and parasites". Biodiversity Data Journal. 3: e5085. doi:10.3897/bdj.3.e5085. PMC 4426341. PMID 25977613.

- Kobilinsky, D. (February 17, 2016). "Rare bumblebee makes comeback". The Wildlife Society. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Evans, E., et al. Status review of three formerly common species of bumble bee in the subgenus Bombus. Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Jepsen, S. Invertebrate Conservation Fact Sheet - Bumble Bees in Decline. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Nguyen, H.; Nieh, J. C. (2012). "Colony and individual forager responses to food quality in the New World bumble bee, Bombus occidentalis" (PDF). Journal of Insect Behavior. 25 (1): 60–69. doi:10.1007/s10905-011-9277-5.

- Dornhaus, A.; Chittka, L. (September 1999). "Evolutionary origins of bee dances". Nature. 401 (6748): 38. doi:10.1038/43372. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Dornhaus, Anna; Chittka, Lars (2001-11-01). "Food alert in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris): possible mechanisms and evolutionary implications". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 50 (6): 570–576. doi:10.1007/s002650100395. ISSN 0340-5443.

- Bentley, B.; Elias, T.s (1983). The Biology of Nectaries. Columbia University Press.

- Cartar, R. V.; Dill, L. M. (1991). "Costs of energy shortfall for bumble bee colonies: Predation, social parasitism, and brood development". The Canadian Entomologist. 123 (2): 283–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.379.6738. doi:10.4039/Ent123283-2.

- Gamboa, G. J.; Foster, R. L.; Richards, K. W. (1987). "Intraspecific nest and brood recognition by queens of the bumble bee, Bombus occidentalis". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 65 (12): 2893–2897. doi:10.1139/z87-439.

- Birmingham, A. L; et al. (2004-12-01). "Drifting bumble bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) workers in commercial greenhouses may be social parasites". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (12): 1843–1853. doi:10.1139/z04-181. ISSN 0008-4301.