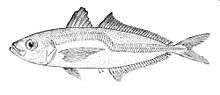

Blue mackerel

The blue mackerel (Scomber australasicus), also called Japanese mackerel, Pacific mackerel, slimy mackerel or spotted chub mackerel, is a fish of the family Scombridae, found in tropical and subtropical waters of the Pacific Ocean from Japan south to Australia and New Zealand, in the eastern Pacific (Hawaii and Socorro Island, Mexico), and the Indo-West Pacific: the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman and the Gulf of Aden, in surface waters down to 200 m (660 ft). In Japanese, it is known as goma saba (胡麻鯖 sesame mackerel). It typically reaches 30 cm (12 in) in length and 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) in weight.

| Blue mackerel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scombriformes |

| Family: | Scombridae |

| Genus: | Scomber |

| Species: | S. australasicus |

| Binomial name | |

| Scomber australasicus Cuvier, 1832 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

Blue mackerel are often mistaken for chub mackerel. In fact, blue mackerel were believed to be a subspecies of chub mackerel until the late 1980s. Though they are both in the same genus (Scomber), blue mackerel set themselves apart by differing structural genes than those of the chub mackerel.[2] Other, more obvious, characteristics set these two apart, like the longer anal spine of the blue mackerel, and the amount of the first dorsal spines.[2] Mackerels have a round body that narrows into the tail after the second dorsal fin, similar to a tuna fish.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Throughout the lives of these mackerel, they tend to stay in areas within a few degrees of 10 °C (50 °F)[4] in tropical to subtropical waters.[2] Off the east coast of North America, populations of mackerel have grown to over 2 million after being depleted in 1982.[4] Blue mackerels can be found from the coast of North America, and as far as Australia and Japan.

Biology and ecology

The blue mackerel is known as a voracious and indiscriminate carnivore, devouring microscopic plankton, krill, anchovies, and dead cut bait, and striking readily on lures and other flies. When in a school and in a feeding frenzy, blue mackerel will strike at nonfood items such as cigarette butts and even bare hooks. They typically eat smaller pelagic fish. Due to their eating habits and their diurnal lifestyles, blue mackerel have evolved large eyes with higher sensitivity in their retinas.[5]

Lifespan

Incubation periods range from 3 to 8 days, growing shorter with warmer temperatures and longer with colder.[4] In the East China Sea, blue mackerel spawn between February and May, when the water temperatures are ideal.[6] In New South Wales, most spawning occurs 10 km (6.2 mi) offshore in waters 100–125 m (328–410 ft) in depth. The Eastern Australian Current can carry eggs and larvae away from the original spawning grounds, broadening the area in which blue mackerel are located. However, egg and larvae probability of surviving decreases the further they are carried by the current.[7] A mature blue mackerel is considered to be over 31 cm (12 in) long.[6] Mackerel can live up to 7 years and grow up to 50 cm (20 in) in length, but are most commonly found to be between 1 and 3 years of age.[8][9] Counting the marks on otoliths determines the age of blue mackerel.[9]

Human interactions

The blue mackerel can be flighty and difficult to catch, especially in estuaries and harbors. From 300 to 500 million tons of blue mackerel have been caught annually since the mid 1980s, without many fluctuations from month-to-month catches. Blue mackerel are caught for both commercial and private use, for food as well as bait for tuna and other fish.[10]

Blue mackerel are often used as cat food, but are also consumed by humans smoked, grilled, or broiled. While easy to fillet and skin, they are difficult to debone, and care must be taken to avoid damaging their soft flesh. Blue mackerel are also commonly used as meat binders. After being freeze-dried, the protein is extracted and put into other meat products to keep the meat and seasonings bound tightly together, allowing costs to be lowered and enhancing the flavor and texture of the product.[11]

References

- Collette, B.; Acero, A.; Canales Ramirez, C.; et al. (2011). "Scomber australasicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T170329A6750490. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170329A6750490.en.

- Tzeng, C.-H.; Chen, C.-S.; Tang, P.-C.; Chiu, T.-S. (2009). "Microsatellite and mitochondrial haplotype differentiation in blue mackerel (Scomber australasicus) from the western North Pacific". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 66 (5): 816–825. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp120.

- "Blue Mackerel". Amalgameted marketing. Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- Studholme; Packer; Berrien; Johnson; Zetlin & Morse (September 1999). Atlantic Mackerel, Life History and Habitat Characteristics. U.S. Department of Commerce.

- Pankhurst, Neville W. (1989). "The relationship of ocular morphology to feeding modes and activity periods in shallow marine teleosts from New Zealand". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 26 (3): 201–211. doi:10.1007/BF00004816.

- Yukami, Ryuji; Ohshimo, Seiji; Yoda, Mari; Hiyama, Yoshiaki (2008). "Estimation of the spawning grounds of chub mackerel Scomber japonicus and spotted mackerel Scomber australasicus in the East China Sea based on catch statistics and biometric data". Fisheries Science. 75 (1): 167–174. doi:10.1007/s12562-008-0015-7.

- Neira, Francisco J.; Keane, John P. (2008). "Ichthyoplankton-based spawning dynamics of blue mackerel (Scomber australasicus) in south-eastern Australia: links to the East Australian Current" (PDF). Fisheries Oceanography. 17 (4): 281–298. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2419.2008.00479.x.

- "Blue Mackerel" (PDF). Wild Fisheries Research Program. I&INSW. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Stewart, John; Ferrell, Douglas J. (2001). "Age, growth, and commercial landings of yellowtail scad (Trachurus novaezelandiae) and blue mackerel (Scomber australasicus) off the coast of New South Wales, Australia". New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 35 (3): 541–551. doi:10.1080/00288330.2001.9517021.

- "Blue Mackerel" (PDF). Wild Fisheries Research Program. I&INSW. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Chung, Yun-Chin; Ho, Ming-Long; Chyan, Fu-Lin; Jiang, Shann-Tzong (2000). "Utilization of freeze-dried mackerel (Scomber australasicus) muscle proteins as a binder in restructured meat". Fisheries Science. 66 (1): 130–135. doi:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2000.00019.x.

External links

- "Scomber australasicus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 18 April 2006.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "Scomber australasicus" in FishBase. March 2006 version.

- Fitch JE (1956) "Pacific mackerel" CalCOFI Reports, 5 29–32.

- Tony Ayling & Geoffrey Cox, Collins Guide to the Sea Fishes of New Zealand, (William Collins Publishers Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand 1982) ISBN 0-00-216987-8

- California Department of Fish & Game, "California Finfish and Shellfish Identification Book" (University of California Press 2007)ISBN 0-9722291-1-6