Bishops Lodge

Bishops Lodge is a heritage-listed former residence and boys' hostel and now house museum at Moama Street, Hay, Hay Shire, New South Wales, Australia. It was built in 1888. It is also known as Linton House Hostel for Boys. The property is owned by Hay Shire Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

| Bishops Lodge | |

|---|---|

| Location | Moama Street, Hay, Hay Shire, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 34.5192°S 144.8483°E |

| Built | 1888–1888 |

| Owner | Hay Shire Council |

| Official name: Bishops Lodge; Linton House Hostel for Boys | |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 482 |

| Type | Homestead building |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

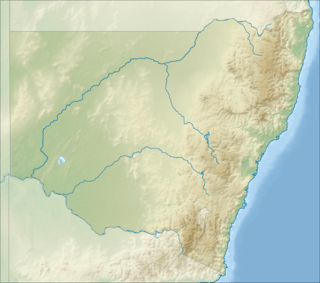

Location of Bishops Lodge in New South Wales | |

History

Establishment of the Anglican Diocese of Riverina

In 1829 Charles Sturt and his men passed along the Murrumbidgee River on horses and drays. During the late-1830s stock was regularly overlanded to South Australia via the Lower Murrumbidgee. At the same time stockholders were edging westward along the Lachlan, Murrumbidgee, Billabong and Murray systems. By 1839 all of the river frontages in the vicinity of present-day Hay were occupied by squatters. By the mid-1850s pastoral runs in the western Riverina were well-established and prosperous. The nearby Victorian gold rush provided an expanding market for stock. The prime fattening country of the Riverina became a sort of holding centre, from where the Victorian market could be supplied as required.[1]

The locality where Hay township developed was originally known as Lang's Crossing-place (named after three brothers named Lang who were leaseholders of runs on the southern side of the river). It was the crossing on the Murrumbidgee River of a well-travelled stock-route (known as 'the Great North Road') leading to the markets of Victoria. In 1856-7 Captain Francis Cadell, pioneer of steam-navigation on the Murray River, placed a manager at Lang's Crossing-place with the task of establishing a store (initially in a tent). In August 1858 steamers owned by rival owners, Francis Cadell and William Randell, successfully travelled up the Murrumbidgee as far as Lang's Crossing-place (with Cadell's steamer Albury continuing up-river to Gundagai). By October 1859 "Hay" had been chosen as the name for the township [after John Hay (later Sir John), a wealthy squatter from the Upper Murray, member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly and former Secretary of Lands and Works]. Hay, situated on the Murrumbidgee, was gazetted as a town in 1859.[2] In the late nineteenth century, several grand buildings representing Hay's aspirations to become the capital of the Riverina were built. However inter-colonial disputes over trade thwarted these aspirations and instead of booming Hay remained small and isolated, but importantly connected to Sydney via a rail line.[3][1]

On 25 May 1882 a meeting was held at Hay Courthouse in support of Hay becoming the new centre of the Riverina Diocese and the site for a cathedral. Hay was centrally located within the Riverina District and the seat of the Bishopric would serve to benefit the social and moral fibre of the town. Paradoxically, at this time Hay could not even support a clergyman's stipend.[1]

The citizens of the rival town of Deniliquin, to the south were also discussing the matter of the residency for the new bishopric. That town was also considered to be a suitable site as it was the largest and one of the oldest of the Riverina towns. In 1882, despite the one hundred and fifteen thousand square miles covered by the new Diocese, Hay and Deniliquin were the largest towns within its boundaries and Narrandera was the only other town, which the Bishop might have even considered as his seat. The Riverina area may have included almost one third of the colony of New South Wales but at that time, prior to mineral discoveries around Broken Hill and the development of irrigation schemes, it was sparsely populated. From December 1881, when the generosity of John Campbell, MLC, enabled the new Diocese to be established with a ten thousand pound bequest, the towns in the western Riverina began vying for the honour of being the cathedral city. A public meeting was held in Hay in May 1882, and the Chairman, H. T. Makin, was reported as saying:

- '...In the event of the Bishop deciding to reside at Hay, a Cathedral would be built here and the town would become a city; the presence of the Bishop in their midst was calculated to improve the tone of society, and would benefit the inhabitants socially, morally and commercially.'[1]

Even in 1882 the leading citizens of Hay were quite confident that the Bishop would select Hay for the many advantages it offered over Deniliquin and Narrandera. Its central location in the Diocese and "...it being directly in communication with the metropolis" would, they felt, assure Hay's selection. They also discussed the need for the people of Hay to pledge financial support to enable the Bishop's residence and cathedral to be built here. Ninety pounds was pledged at this meeting.[1]

At the request of the Anglican Diocese of Goulburn, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of York and the Bishop of London selected the first Bishop of Riverina. On 17 November 1883 the position was offered to the Right Reverend Sydney Linton.[4][1]

Sydney Linton arrived with his wife and family in Sydney on board the Parramatta in early 1885 and was enthroned as the Anglican Bishop of the Riverina at St Paul's Church, Hay on 18 March of that same year. He travelled extensively throughout the area during his early ministry and experienced the extremes of the Riverina climate and had ample opportunity to consider the design of a building to accommodate his family and the administrative needs of the diocese. The result is an innovative and successful building constructed in 1888.[1]

The Bishop's Lodge residence was constructed in Hay by Bishop Linton after promises of support from the Mayor and people of Hay. These promises were not fulfilled and the Linton family bore the major part of the debt for construction after the Bishop's death. The diocesan headquarters were later transferred to Narrandera.[1]

Residence of the Bishop of Riverina

Bishop Linton employed the architectural practice of Sulman and Parkes, based in Sydney, and the plans for Bishop's Lodge were drawn by John Sulman, incorporating Linton's many ideas for climate control. John Sulman, born in 1849, left a thriving practice in England when he and his invalid wife migrated to New South Wales in 1885. He was a highly successful and respected architect whose practice in the colony also prospered and he remained a partner in the firm Sulman and Power until 1928. His contribution to his profession also included teaching. From 1887 until 1912 he lectured in architecture in the Faculty of Engineering at Sydney University and from 1916 to 1927 he was again at the university, lecturing in Town Planning. It would appear that Bishop's Lodge stands alone in his work, being quite atypical of his style. Much of his work featured Italianate detailing and was constructed in brick and or stone. Comparisons with other examples of his work from the same period as Bishop's Lodge would appear to confirm Bishop Linton's major influence in the design and materials for the Lodge. For example, the Yaralla Cottages in Concord, Sydney, were also completed in 1889, but in an English Queen Anne Revival style with what has been described as 'archetypical Sulmanesque marriage of brick and finely carved sandstone detailing.[4][1]

Thus Hay became the cathedral city of the new Diocese. The population then, as now, was approximately three thousand people. At that time Hay was an established town in the centre of the vast Riverina plains, with many imposing public buildings and urban services such as reticulated water. St Paul's pro-cathedral was erected by the end of 1885, the original plans to build a school room and synod hail having been hastily re-arranged and improved upon in order to create a "temporary" cathedral.[1]

Finally, in 1890 Bishop Linton and his family were able to move into their new, almost completed, residence. The Bishop wrote that:

- ... "The home surpasses all our utmost expectations, for comfort, convenience, and for beauty. The painting of the interior iron walls is lovely, and is done in admirable taste, the exterior is quite plain, but not ugly, having no ornamentation beyond the Christian sign over the main entrance, and a [bishop's] mitre carved in the woodwork. We can now speak of the house as being admirable for a summer residence, and cool beyond any other in town. The thermometer has never exceeded 90 degrees within the house. The chapel will look very well when finished. It has a painted glass window manufactured in Sydney, from instructions given by me.'.[4][1]

When the Lintons moved into the new and nearly finished Bishop's Lodge in September 1889, a substantial fence surrounded about eight acres, which comprised the home grounds. Here the ground was ploughed to a depth of 18 inches and four hundred trees, both fruit and ornamental, were planted over a three-month period that spring. A further thirteen acres of paddock lay immediately to the south. This was an area subject to flooding by the Bungah Creek, and the Bishop felt it would be exceedingly valuable for the cultivation of horse feed and fruit trees, if irrigated. It was separated from the Lodge by Moama Street, which is now the Sturt Highway.[1]

The early garden suffered two major setbacks. In November 1890 an extraordinary plague of locusts stripped the entire garden, eating all the vegetables and flowers and the leaves and young shoots of the fruit trees, in some cases ring-barking the stems. This was despite great efforts by Bishop Linton and all at hand to prevent damage by lighting fires and filling the garden with murky smoke and also beating around the garden with sacks. According to Bishop Linton every garden within a hundred-mile radius was equally attacked, only the older, more established gardens were better able to survive the locusts.[1]

In October 1891 a flood inundated half of the home grounds, the river being twenty-five feet above the usual summer level. Some portions of the garden were four feet under water and many fruit trees were flooded for several weeks. The house remained four feet above the flood-water. Bishop Linton wrote that most of the Chinese market gardens around Hay were inundated and supplies had to be brought in from Sydney. The Bishop's Lodge vegetable gardens were better off than most, as the beds then currently in use were above flood level, however he did note that their strawberries, asparagus and rhubarb were out of sight and would probably perish. The flood-prone aspect of some of the grounds would explain the way in which the garden has developed.[1]

By the early 1890s Linton's diocese covered over a third of New South Wales but included few more than 20,000 Anglicans; many of the landholders were absentees or non-Anglicans while the mines at Broken Hill were attracting increasing numbers of Methodists. In an effort to make his diocese an effective unit of the Church, Bishop Linton had set up regular diocesan institutions. A Church Society was founded in 1885 to build up a central fund and promote the extension of work in the diocese. The first synod met in 1887 and by 1890 its constitution was in good order. He recruited new clergy, his staff of six in 1885 had by 1893 increased to eighteen. Churches were built and new parishes were formed and the diocese was enlarged by the accession of the township of Wilcannia from the Bathurst diocese.[4][1]

Bishop Sidney Linton died in 1894. Almost immediately the Church authorities turned to the question of the Diocesan debt incurred in Bishop's Lodge. The responsibility for the debt had now shifted from the Bishop himself, to the diocese.[1]

Bishop Ernest Augustus Anderson was installed as the new Bishop of Riverina in 1894. He was consecrated at St Paul's Cathedral, London, on 29 June the next year, then raised money for his diocese before returning to New South Wales, and he was installed in St Paul's Pro-Cathedral at Hay on 11 February 1896. Bishop Anderson had had experience in Queensland with similar bush conditions to those he met in the Riverina Diocese, now a see of over 70,000 square miles, with fourteen parishes worked by fifteen clergy. He was faced immediately with the financial collapse of his diocese.[1]

As early as 1897 the matter of the Bishop's stipend was being aired publicly: '...A telegram from Hay states that prompt steps are being taken to secure to Bishop Anderson the salary which was attached to his office upon his being raised to the episcopate. The salary was then (Pounds)1,000 per annum, but owing to losses of revenue it is now only half that amount.'[1]

The financial collapse was partly due to the debt on Bishop's Lodge, and partly to the fact that the diocesan Episcopal Endowment fund had been largely depleted through the dishonesty of a solicitor. After two court cases, by 1915 some £11,000 of the original £15,000 had been rescued. Meanwhile, Anderson had been paid less than half the annual £800 he had been promised and had spent his personal fortune in maintaining his position as bishop, furnishing Bishop's Lodge and educating his children; it was twenty-two years before he was free of debt.[4][1]

Dr Ernest Anderson with his wife, Aimee, and their four children, the oldest of whom, Constance, was eleven years old, had moved into Bishop's Lodge in 1895. Henrietta was nine, Sleeman was five and Ralph was four when they arrived in Hay. Two further daughters were born after the family moved to Hay, Mary in 1898 and Joy in 1900.[4][1]

Thus Bishop Anderson's household was the same size as the Linton family and they found Bishop's Lodge provided spacious accommodation. At the time of arrival in Hay, Bishop Anderson was thirty-six and a man of great activity and physical strength, essential attributes for what was still largely a pioneering role. Bishop Anderson was also a man of considerable artistic sensitivity. He collected china, developed extensive rose gardens both in Hay and New Zealand and painted and sketched. His mural painted on the eastern wall of the Pro-Cathedral was a feature of the Church until the mural was damaged by fire in 1964. He was described as a hard worker and vigorous preacher who held broad views.[1]

The staff at Bishop's Lodge during much of the Andersons' time was a married couple, Mr and Mrs Bond, who lived in the rooms off the kitchen. Mrs Annie Bond was the cook and Mr Bond worked in the garden. There was also a parlour maid and a governess who came in daily from Hay. The Chinese gardener, Ah Mow, had been engaged by Bishop Linton in the early 1890s and was still at Bishop's Lodge in 1921.[1]

Over the thirty years of Bishop Anderson's episcopacy his family grew and their occupancy of Bishop's Lodge changed. During the first fifteen years it was a family of young children, enjoying beach holidays at Portarlington, playing with dogs, cats and ponies, holding tennis parties and having lessons either with a governess or at the private Hay Grammar School run by Mrs Gegg, wife of the manager of the Bank of New South Wales. The Bishop was frequently away from home for weeks at a time as he travelled to all parts of his Diocese. From 1915 motorcars made diocesan travel easier, but Anderson still had to make long annual tours on unmade roads. During Anderson's episcopate thirty-two churches and many rectories were built and the number of clergy increased. Diocesan finances after 1920 were stable.[1]

By 1924, when Bishop Anderson announced his retirement, many in the Diocese felt Bishop's Lodge had become unsuitable as the Bishop's residence. Its upkeep had been a great burden on the Bishop, made much more so by the small income he had been obliged to accept because of mismanagement of the Diocesan Trust Fund. Unwise investments by the Diocesan solicitors in Goulburn had seriously depleted the capital of the Bishopric Endowment Fund and the Pioneer Clergy Fund.[1]

Bishop Anderson's entire episcopate was plagued by financial worries as a result of the "roguery of a certain solicitor". The much reduced income he received meant he was obliged to use almost his entire private capital of between £5000 and £6000 in meeting the expense of educating his family and running the Bishop's Lodge household. As a result, he was obliged to seek a retirement allowance from the synod and in 1924 it discussed the establishment of a Retirement Fund, the interest from which would provide retirement incomes for all future Bishops. Bishop Anderson received an annual retirement income of £360. During his episcopacy Bishop Anderson also took upon himself the task of trying to rebuild the capital in the Episcopal Endowment Fund and managed to raise £9000 in his many trips around the diocese. This was added to the £11000 eventually recovered from the original fund of £15000. Thus Bishop Anderson actually left the diocese on a very sound financial footing, having inherited such a financial problem. By 1918 Bishop Anderson had also managed to pay off the loans taken to build Bishop's Lodge, thirty years earlier. As the time approached for the Bishop's resignation, the diocese publicly considered the future for the large and financially draining Bishop's Lodge property.[1]

From all accounts Bishop Anderson had no reason to be ashamed of Bishop's Lodge or its garden. The garden had flourished and was renowned for the roses he had planted. Despite Canon Kitchen's misgivings the house continued to be of use to the Anglican Church until 1946. Within the Linton incumbency, there had been a formal entrance from Lang Street with a wide carriage-way leading to the turning circle in front of the building, but for most of the twentieth century only a walking path down the centre of the carriageway has been maintained for pedestrian visitors to the Lodge. As far back as Bishop Anderson's time the Roset Street entrance has been known as the "front gate". By about 1915, when Bishop Anderson and his family had been in residence for twenty years, the view from the front verandah of the Lodge was one of well kept lawns and beautifully tended gardens on every side. There were large rose bushes in the middle of the circular lawn and well-grown shrubs in the beds on the eastern side of the front garden. The pepper trees and the plane tree were well grown.[4][1]

The extensive rose garden was north of the driveway as one entered from Roset Street. Bishop Anderson was an enthusiastic gardener who loved his roses. He bought them from many sources and enjoyed exhibiting them. Every rose bush was labelled with a metal plate fixed to a peg. What is now called the "hidden garden" was then an enclosed rose garden, which could he clearly seen from the entrance; but subsequent growth has concealed it. Some of the original posts and high wire netting remain there, chicken wire below and large gauged marsupial wire above. All of the rose bushes within are believed to have been planted by Bishop Anderson. He also had orange and lemon trees around beds in the rose garden. During Bishop Anderson's time there was a summer-house on the northern boundary of the enclosed rose garden. It was built of wood and had seats within. A rose-covered archway over the central path of the rose garden lead to the summer-house. Bishop Anderson also had a little bush house for the propagation of seedlings and housing of pot plants on the western side of the house, close to the verandah.[4][1]

The wide access to Lang Street and the river, which was directly in line with the front door, was generally used as a footpath. Flanking this main path for its entire length were trellises made of pine poles threaded with wire on which the Chinese gardener, Ah Mow, grew all kinds of white and black table grapes. Rosemary and lavender grew below the trellises. Ah Mow kept a vegetable garden in the north west corner of the grounds just inside the Lang Street gates. He also kept a vegetable garden at the back [south] of the building. As well as providing for the family he sold produce to the public, travelling around town with a horse and cart. Ah Mow lived at the stables and was a well-known fixture at Bishop's Lodge. He had been engaged by Bishop Linton, presumably in the early 1890s, and was still part of the Bishop's Lodge establishment in 1921. There was usually another gardener to tend the rest of the garden. Often a married couple was employed as gardener and cook. Between the circular drive and Ah Mow's vegetable garden adjacent Lang Street was an orchard.[4][1]

The stables became home to the Dean family at some stage in the 1920s, probably when the Bishop acquired a car and no longer used the stables for their intended purpose. The Deans were a large family, sleeping upstairs in the loft and living downstairs. The lower floor remained as packed earth and their kitchen was in the pump house a little way from the stables. They continued living at the stables until the early 1940s when Mr Dean died and the family dispersed. The stables were presumably pulled down at that stage and were no longer standing in 1945.[1]

In the 1930s and 1940s Chinese market gardens flourished on the riverbank just over the washaway to the west. They supplied the Linton House hostel with all its vegetables. For a time there was a tennis court in the north-east corner of the Bishop's Lodge grounds. It was probably on the same site as the [later] boy's hostel tennis court, which was established in 1935 [about where Mr and Mrs Munn's house is now situated, at 352 Lang Street]. The Anderson children would often hold tennis parties.[4][1]

Two weeks before the departure ceremony for Bishop Anderson Bishop's Lodge was offered for sale. Advertisements for the sale of the building were to continue for another four months, until 24 March 1925. The absence of a willing buyer obviously forced the diocese to reconsider its decision to dispose of the Lodge, for six months later the newly incumbent Bishop Reginald Halse took up residence there.[1]

Pursuant to the proposed sale of Bishop's Lodge, and Bishop Anderson's removal to New Zealand the whole contents of Bishop's Lodge were offered in a clearing sale to be held on 10 December 1924. The list of items, and corresponding rooms, gives an understanding of the way in which the Lodge was used by Bishop Anderson and his family.[4][1]

In 1925 Bishop Halse was appointed Bishop of the Riverina. He was quoted as saying he would divide his time as Bishop into three. A third to be spent in Hay, a third travelling around the diocese, and the remaining third being spent travelling outside the Diocese serving the wider Church. During the early years of Halse's episcopacy Bishop's Lodge was often empty. Given the Church's unsuccessful attempts to sell the building during 1925, little maintenance was carried out and the Lodge often wore a rather deserted appearance.[1]

During the early period of Bishop Halse's incumbency, the grounds, which still extended down to Lang Street, are remembered as extensive gardens of trees and shrubs dissected by a number of paths where young clerics could occasionally be seen at their devotions.[1]

Between 1931 and 1935 a Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis) was planted on the circular front lawn and pencil pines (/Mediterranean cypresses, Cupressus sempervirens) on the eastern front lawn. It was some time after 1931 that the thick olive hedge (Olea europaea), which extended from the Lang Street gates to Roset Street, was cleared.[1]

In 1935 the nearby portion of land was cleared for the Linton House tennis court. The olive hedge remained along Roset Street, billowing out over the fence at head height. There was a gate in the Roset Street fence immediately east of the kitchen block, used by the staff and for delivery of goods to the kitchen.[1]

Bishop Halse greatly enjoyed the Bishop's Lodge garden and it continued to be well maintained during his episcopacy. He decreed that there should be no blinds or curtains on the dining room windows, saying that a garden was for looking at. By about 1940 the garden between the building and the Roset Street gate was an immaculately kept lawn bordered by flower beds and containing circular flower beds and three young pencil pines. The dense shrubbery of 1915 had been removed completely.[1]

Linton House Hostel for Boys

Nine years after Halse's arrival and halfway through his incumbency as Bishop of Riverina, the decision was taken to convert part of the Lodge for use as a boy's hostel. In 1935 a large part of the house was adapted for it to become the Linton House Hostel for Boys. Bishop's Lodge was seen to be admirably suitable with its large house and spacious grounds providing plenty of space for tennis, cricket and football. The addition of a swimming beach close by and good fishing from the Murrumbidgee River banks completed its attributes as a boys' hostel. The hostel operated successfully at Bishop's Lodge until the Diocese finally found a purchaser for the building in 1946. The Matron was ordered to close the Hostel on the 13th of December that year.[4][1]

Private ownership

In 1943, Bishop Halse left the diocese and the Lodge. On 20 December 1946, the Anglican Diocese of Riverina finally (after the diocese's twenty-two-year search for a buyer) arranged the sale of the Lodge. On that day it was sold to Mr Nick Panaretto and Mrs Kerany Carides. Neither the Carides nor the Panarettos had children and the four of them lived comfortably in Bishop's Lodge until first Mr Panaretto's death in 1964, then Mrs Carides' death in 1973. Mr Carides died in 1980, and, after living alone in the house for five years, Mrs Panaretto negotiated to sell the property to the Hay Shire Council in 1985.[4][1]

House museum

In 1985 Council purchased the property and have since run it as a community house museum and for events. In 1988 the Bishop's Lodge Advisory Committee planted fifty old-fashioned roses in the eastern front lawn in beds, which corresponded with earlier beds that bounded the driveway. Roses, believed to have been introduced to the garden by Bishop Anderson, have been budded onto hardy under-stock by specialists. It is the Bishop's Lodge Management Committee policy that the garden should complement the house. Various factors, including floods and fashions, have, over the years, dictated changes and usage of the grounds. It is not intended to present a garden style of a particular period, but to preserve the special feeling of the garden: replace some of what is documented as existing in the garden, resist the temptation to over-zealously prune and clear and carefully develop this garden which has been loved for more than one hundred years.[4][1]

Description

This imposing building is located with a north orientation to the Murrumbidgee River. An unobstructed view of the building from the Sturt Highway ensures that the building is a landmark feature in the Hay area and Riverina. Orientation was carefully considered in the layout and siting of the residence, rather than it facing the street. An unobstructed view of the building from the Sturt Highway ensures that the building is a landmark feature in the Hay area and Riverina.[1]

- Garden

Bishop's Lodge retains a large country garden, particularly north of the house towards the river. It is particularly rich in old (or 'heritage') roses). The garden has a ready band of volunteers who have revived it and keep it in good condition.[1]

Within the Linton incumbency, there was a formal entrance from Lang Street with a wide carriage-way leading to the turning circle in front of the building, but for most of the 20th century only a walking path down the centre of the carriageway has been maintained for pedestrian visitors. From Bishop Anderson's time the Roset Street entrance has been known as the "front gate". By about 1915 the view from the front verandah was of well kept lawns and beautifully tended gardens on every side. There were large rose bushes in the middle of the circular lawn and well-grown shrubs in the beds on the eastern side of the front garden. The pepper trees (Schinus molle) and the plane tree (Platanus x hybrida) were well grown.[1]

The extensive rose garden was north of the driveway as one entered from Roset Street. Anderson was an enthusiastic gardener who loved roses. Every rose bush was labelled with a metal plate fixed to a peg. What is now called the "hidden garden" was then an enclosed rose garden; subsequent growth has concealed it. Some original posts and high wire netting remain there, chicken wire below and large gauged marsupial wire above. All the rose bushes within are believed to have been planted by Anderson. He also had orange (Citrus x aurantium cv.) and lemon (C.limon cv.) trees around beds in the rose garden. During Anderson's time there was a summer-house on the northern boundary of the enclosed rose garden built of wood with seats within. A rose-covered archway over the central path of the rose garden led to the summer-house. Anderson also had a little bush house on the western side of the house, close to the verandah.[1]

The wide access to Lang Street and the river, directly in line with the front door, was generally used as a footpath. Flanking this path for its entire length were trellises of pine poles threaded with wire on which grew all kinds of white and black table grapes. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and lavender (Lavandula sp.) grew below the trellises. A vegetable garden was in the north west corner just inside the Lang Street gates. Another vegetable garden was at the back [south] of the building. Between the circular drive and Ah Mow's vegetable garden adjacent Lang Street was an orchard.[1]

The stables became home to the Dean family at some stage in the 1920s, probably when the Bishop acquired a car and no longer used them. Their kitchen was in the pump house a little way from the stables. They continued living at the stables until the early 1940s when Dean died and the family dispersed. The stables were no longer standing in 1945.[1]

In the 1930s and 1940s Chinese market gardens flourished on the riverbank just over this washaway to the west. For a time there was a tennis court in the north-east corner of the grounds, probably on the same site as the [later] boy's hostel tennis court, established in 1935 [about where Mr and Mrs Munn's house is now situated, at 352 Lang Street].[1]

Between 1931 and 1935 a Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis) was planted on the circular front lawn and pencil pines (/Mediterranean cypresses, Cupressus sempervirens) on the eastern front lawn. It was some time after 1931 that the thick olive hedge (Olea europaea), which extended from the Lang Street gates to Roset Street, was cleared.[1]

In 1935 the nearby portion of land was cleared for the Linton House tennis court. The olive (Olea europaea cv.) hedge remained along Roset Street, billowing out over the fence at head height. There was a gate in the Roset Street fence immediately east of the kitchen block, used by the staff and for delivery of goods to the kitchen.[1]

By about 1940 the garden between the building and the Roset Street gate was an immaculately kept lawn bordered by flower beds and containing circular flower beds and three young pencil pines. The dense shrubbery of 1915 had been removed completely.[1]

In 1988 the Bishop's Lodge Advisory Committee planted fifty old-fashioned roses in the eastern front lawn in beds, which corresponded with earlier beds that bounded the driveway. Roses, believed to have been introduced to the garden by Bishop Anderson, have been budded onto hardy under-stock by specialists. Some old roses in the garden were propagated from the original rose garden at Oxley Station near Hay. It is the Bishop's Lodge Management Committee policy that the garden should complement the house. Various factors, including floods and fashions, have, over the years, dictated changes and usage of the grounds. It is not intended to present a garden style of a particular period, but to preserve the special feeling of the garden: replace some of what is documented as existing in the garden, resist the temptation to over-zealously prune and clear and carefully develop this garden.[1]

- House group

The lodge comprises the main residence, a kitchen block and two outbuildings east of the kitchen. The residence has a courtyard open to the rear, and a verandah encircles the building. All rooms are accessible from the verandah and a central hall is the only internal passageway. Walls are clad externally in corrugated iron and internally in ripple iron, with sawdust within the walls for insulation. Finely detailed verandah posts, window and door mouldings, roof ventilators and skilfully mitred timber linings on the verandah soffits provide relief from the bland corrugated walls. Wisteria grows on the northern verandah and adds protection from the sun.[1]

The construction system was innovative, to avoid the problems of soil movement in the extremes of seasons which cause masonry buildings to crack and to allow the structure to cool rapidly at night in the summer, while being insulated from the worst of the daytime heat. The roof is hipped, with ventilators in the portion of walls between the verandah roofs and the main eaves. There are gambrel ventilators to the rear hips. The chimneys are of brick. There is a pediment at the entrance, with incised decoration around a Bishop's mitre (AHC).[1]

It is a large single storey building with central courtyard and with encircling verandah around the building perimeters. All rooms are accessible from the verandahs with a central hallway the only internal passageway.[1]

Roofing and external walls of corrugated iron and internal linings all of ripple iron on a timber frame with sawdust filled wall cavities to provide insulation. In southern New South Wales, iron is a most suitable domestic building material. Its lightness and durability and ability to withstand the seasonal expansion and contraction of western Riverina soil which causes extensive cracking of masonry buildings has not been generally appreciated. As a result, many period iron houses have been lost. Rather than facing south onto the main road, the building has a northern orientation which is further evidence of design concessions to climatic extremes.[1]

The utilitarian plainness of the building is relieved by finely detailed timber verandah posts, window and door mouldings, roof ventilators. A timber pediment over the entrance has a finely incised decoration around a carved bishop's mitre. Internally there are eighteen rooms each about 25 ft by 25 ft. The 12 ft high ceilings are of stained boards. Each room has a marble fireplace - black, brown or white - with brick surrounds. The former chapel has a decorated arch and stained glass fanlight.[1]

- Kitchen Block

The kitchen block with large kitchen and several small rooms is connected to the house by a raised covered walkway.[1]

Heritage listing

This is an important and increasingly rare example of a large intact iron house typical of nineteenth-century Riverina domestic architecture. It demonstrates by its positioning and materials the necessary adaptation and concessions made to the local climatic extremes and the nature of the soils. Its design is thought to have influenced the choice of materials used for the Hay Lands Office built in 1895.[1]

Bishops Lodge was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

See also

References

- "Bishops Lodge". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00482. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- DUAP et al, Regional Histories, pp194

- Hay Council SHI nomination 2006

- Freeman, 2010

Bibliography

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Bishops Lodge". Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- LAUREL, CLYDE. IN A STRANGE LAND.

- Mary Lous Gardam, Brenda Weir, Peter Freeman (2003). The Bishop's Lodge, Hay, NSW, Australia.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- National Trust of Australia (NSW) (1984). Classification Sheet #2933.

- PETER, FREEMAN (1982). THE HOMESTEAD: A RIVERINA ANTHOLOGY.

- Peter Freeman P/L (2010). Conservation Management Plan - Bishop's Lodge, Hay, NSW.

- Tourism NSW (2007). "Bishops Lodge Historic House Heritage Rose Garden".

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()