Bird's wing

The bird's wing is a paired forelimb in birds. The wings give the birds the ability to fly, creating lift.

Terrestrial flightless birds have reduced wings or none at all (for example, moa). In aquatic flightless birds (penguins), wings can serve as flippers.[1]

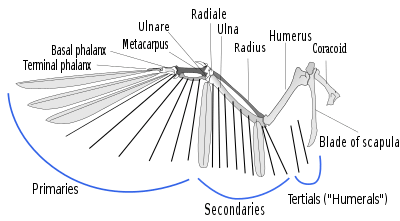

Anatomy

Like most other tetrapods, the forelimb of birds consists of the shoulder (with the humerus), the forearm (with the ulna and the radius), and the hand.

The bird's hand is strongly transformed: some of its bones have been reduced, and some others have merged with each other. Three bones of the metacarpus and part of the carpal bones merge into a carpometacarpus. The bones of three fingers are attached to it. The frontmost one bears an alula - a group of feathers that act like the slats of an airplane. This finger usually has one phalanx bone, the next - two, and the back - one (but some birds have one more phalanx on the first two fingers - the claw).

Finger identity problem

.png)

The bones of three fingers are preserved in the bird's wing. The question of which fingers they are has been discussed for about 150 years, and an extensive literature is devoted to it.[2][3] The Anatomical, paleontological and molecular, data show that these are fingers 1, 2 and 3, and embryological - that these are fingers 2, 3 and 4.[1] Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this discrepancy. Most likely, in birds, finger buds 2-4 began to follow the genetic program for the development of fingers 1–3.[3]

Wing shape

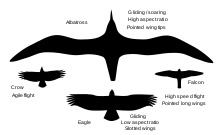

The shape of the wing is important in determining the flight capabilities of a bird. Different shapes correspond to different trade-offs between advantages such as speed, low energy use, and maneuverability. Two important parameters are the aspect ratio and wing loading. Aspect ratio is the ratio of wingspan to the mean of its chord (or the square of the wingspan divided by wing area). Wing loading is the ratio of weight to wing area.

Most kinds of bird wing can be grouped into four types, with some falling between two of these types. These types of wings are elliptical wings, high speed wings, high aspect ratio wings and soaring wings with slots.

Elliptical wings

Technically, elliptical wings are those having elliptical (that is quarter ellipses) meeting conformally at the tips. The early model Supermarine Spitfire is an example. Some birds have vaguely elliptical wings, including the albatross wing of high aspect ratio. Although the term is convenient, it might be more precise to refer to curving taper with fairly small radius at the tips. Many small birds have having a low aspect ratio with elliptical character (when spread), allowing for tight maneuvering in confined spaces such as might be found in dense vegetation. As such they are common in forest raptors (such as Accipiter hawks), and many passerines, particularly non-migratory ones (migratory species have longer wings). They are also common in species that use a rapid take off to evade predators, such as pheasants and partridges.

High speed wings

High speed wings are short, pointed wings that when combined with a heavy wing loading and rapid wingbeats provide an energetically expensive, but high speed. This type of flight is used by the bird with the fastest wing speed, the peregrine falcon, as well as by most of the ducks. The same wing shape is used by the auks for a different purpose; auks use their wings to "fly" underwater.

The peregrine falcon has the highest recorded dive speed of 242 mph (389 km/h). The fastest straight, powered flight is the spine-tailed swift at 105 mph (170 km/h).

High aspect ratio wings

High aspect ratio wings, which usually have low wing loading and are far longer than they are wide, are used for slower flight. This may take the form of almost hovering (as used by kestrels, terns and nightjars) or in soaring and gliding flight, particularly the dynamic soaring used by seabirds, which takes advantage of wind speed variation at different altitudes (wind shear) above ocean waves to provide lift. Low speed flight is also important for birds that plunge-dive for fish.

Soaring wings with deep slots

These wings are favored by larger species of inland birds, such as eagles, vultures, pelicans, and storks. The slots at the end of the wings, between the primaries, reduce the induced drag and wingtip vortices by "capturing" the energy in air flowing from the lower to upper wing surface at the tips,[4] whilst the shorter size of the wings aids in takeoff (high aspect ratio wings require a long taxi to get airborne).[4]

References

- Vargas, A. O.; Fallon, J. F. (2005). "The Digits of the Wing of Birds Are 1, 2, and 3. A Review". 304 (3) (Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution ed.): 206–219. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21051. PMID 15880771. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Baumel, J. J. (1993). Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club. pp. 45–46, 128.

- Young, R. L; Bever, G. S.; Wang, Z.; Wagner, G. P. (2011). "Identity of the avian wing digits: Problems resolved and unsolved". 240 (5) (Developmental Dynamics ed.): 1042–1053. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22595. PMID 21412936. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tucker, Vance (July 1993). "Gliding Birds: Reduction of Induced Drag by Wing Tip Slots Between the Primary Feathers". Journal of Experimental Biology. 180: 285–310.