Biomphalaria tenagophila

Biomphalaria tenagophila is a species of air-breathing freshwater snail, an aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Planorbidae, the ram's horn snails.

| Biomphalaria tenagophila | |

|---|---|

| |

| Apical, apertural and umbilical views of the shell of Biomphalaria tenagophila. Scale bar is 3 mm. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | Planorbinae |

| Tribe: | Biomphalariini |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. tenagophila |

| Binomial name | |

| Biomphalaria tenagophila | |

| Synonyms | |

This species is medically important pest,[3] because of transferring the disease intestinal schistosomiasis. (Intestinal schistosomiasis is the most widespread of all types of schistosomiasis).

The parasite Schistosoma mansoni, which Biomphalaria snails carry, infects about 83.31 million people worldwide.[4]

The shell of this species, like all planorbids is sinistral in coiling, but is carried upside down and thus appears to be dextral.

Taxonomy

Biomphalaria tenagophila was originally discovered and described under the name Planorbis tenagophilus by the French naturalist Alcide d'Orbigny in 1835.[1] Orbigny (1835) referred its distribution to Corrientes Province, Argentina and to Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia (referred as "Santa-Cruz et Chiquitos"). But Orbigny himself later limited its distribution to Ensenada, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina in 1837.[5]

Subspecies recognized in this species include:

- Biomphalaria tenagophila tenagophila (d’Orbigny, 1835)

- Biomphalaria tenagophila guaibensis Paraense, 1984[5] - Biomphalaria tenagophila guaibensis can be distinguished from the nominal subspecies according to the details on the reproductive system only.[5]

There are also three "old-style" proposals of subspecies, based on shell characteristics:[5]

- Planorbis tenagophilus chemnitziana Beck, 1837 - this name is based on the catalog for the shell in Museum of Copenhagen, but without description.[5]

- Planorbis tenagophilus orbignyana Beck, 1837 - the same situation as in P. t. chemnitziana[5]

- Australorbis bahiensis megas Pilsbry, 1951[6]

History of discoveries summarized Paraense (2001).[7]

Phylogeny

A cladogram showing phylogenic relations of species in the genus Biomphalaria:[8]

| Biomphalaria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution

Biomphalaria tenagophila is a Neotropical[3] species and its native distribution include Peru,[9] Brazil, Uruguay[5] and Argentina.

This species has recently expanded its native range.[3][10]

The non-indigenous distribution of Biomphalaria tenagophila includes a hypothermal spring near Răbăgani, Romania (46°45´1.3´´N, 22°12´44.8´´E).[10]

Shell description

The shell is sinistrally coiled (has left-handed coiling). The flat shells are yellow-brown, discoidal, deeply and symmetrically biconcave, and consist of 5 or 6 slowly increasing whorls. The last whorl is rounded; the intermediate whorls are slightly angled on the left side. The aperture is circular or slightly ovate and angled toward the left side of the shell (i.e., toward the upper surface on the bottom right shell). Fine, parallel, rib-like transverse lines can be seen on the outer surface of the whorls.[10]

The width of the shell is usually from 11 to 13 mm,[10] but in the largest individuals, the shell can reach 21 mm in width, 6.5 mm in height and have 6.5 whorls.[5]

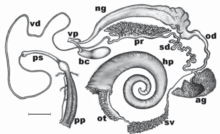

A shell of Biomphalaria tenagophila. |

ag - albumin gland

bc - bursa copulatrix

hp - distal part of the hepatopancreas

ng - nidamental gland

od - oviduct

ot - ovotestis

pp - preputium

pr - prostate

ps - penis sheath

sd - spermiduct

sv - seminal vesicles

vd - vas deferens

vp - vaginal pouch.

Anatomy

The anatomy of this species was firstly published under the synonym Australorbis nigricans in 1955.[11]

The body length varies from 56 mm to 64 mm.[11]

The radula has from 125 to 168 rows of denticles (tiny teeth). The number of lateral teeth varying from 28 to 36. The mode radula formula is 31-0-31.[11]

The specific characteristics of the reproductive system of Biomphalaria tenagophila are: more than 200 diverticulae of the ovotestis; 7–11 main lobes of the prostate; and presence of vaginal pouch.[10]

Ecology

Habitat of Biomphalaria tenagophila is tropical standing water or freshwater.[10]

Biomphalaria tenagophila is an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni and a vector of schistosomiasis.[12] Schistosoma mansoni came to Neotropics from Africa in context of the slave trade.[8] Schistosoma mansoni was not able to infect Biomphalaria tenagophila in 1916 and it has adapted to this host since 1916.[8]

Experimental parasites include:

- Angiostrongylus vasorum - (experimental)[13]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference.[10]

-

-

- Pointier, J. P.; Pointier, J. P.; David, P.; Jarne, P. (2005). "Biological invasions: The case of planorbid snails". Journal of Helminthology. 79 (3): 249–256. doi:10.1079/JOH2005292. PMID 16153319.

- Crompton, D. W. (1999). "How much human helminthiasis is there in the world?" (PDF). The Journal of Parasitology. 85 (3): 397–403. doi:10.2307/3285768. JSTOR 3285768. PMID 10386428. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-23.

- Paraense, W. L. (1984). "Biomphalaria Tenagophila Guaibensis ssp. N. From Southern Brazil and Uruguay (pulmonata: Planorbidae). I. Morphology". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 79 (4): 465–469. doi:10.1590/S0074-02761984000400012.

- Pilsbry, H. A. (1951). "Notes on some Brazilian Planorbidae". Nautilus. 65 (1): 3–6.

- Paraense W. L. (2001) "The Schistosome Vectors in the Americas". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 96(Supplement): 7-16. text Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, PDF Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Dejong, R. J.; Morgan, J. A.; Paraense, W. L.; Pointier, J. P.; Amarista, M.; Ayeh-Kumi, P. F.; Babiker, A.; Barbosa, C. S.; Brémond, P.; Pedro Canese, A.; De Souza, C. P.; Dominguez, C.; File, S.; Gutierrez, A.; Incani, R. N.; Kawano, T.; Kazibwe, F.; Kpikpi, J.; Lwambo, N. J.; Mimpfoundi, R.; Njiokou, F.; Noël Poda, J.; Sene, M.; Velásquez, L. E.; Yong, M.; Adema, C. M.; Hofkin, B. V.; Mkoji, G. M.; Loker, E. S. (2001). "Evolutionary relationships and biogeography of Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) with implications regarding its role as host of the human bloodfluke, Schistosoma mansoni". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (12): 2225–2239. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003769. PMID 11719572.

- Paraense, W. L. (2003). "Planorbidae, Lymnaeidae and Physidae of Peru (Mollusca: Basommatophora)" (PDF). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 98 (6): 767–771. doi:10.1590/s0074-02762003000600010. PMID 14595453.

-

- Paraense, W. L.; Deslandes, N. (1955). "Observations on the morphology of Australorbis nigricans". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 53 (1): 121–134. doi:10.1590/s0074-02761955000100012. PMID 13265240.

- Borda, C. E.; Rea, M. J. F. (2007). "Biomphalaria tenagophila potencial vector of Schistosoma mansoni in the Paraná River basin (Argentina and Paraguay)" (PDF). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 102 (2): 191–195. doi:10.1590/s0074-02762007005000022. PMID 17426884.

- Pereira, C. A. J.; Martins-Souza, R. L.; Coelho, P. M. Z.; Lima, W. S.; Negrão-Corrêa, D. (2006). "Effect of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection on Biomphalaria tenagophila susceptibility to Schistosoma mansoni". Acta Tropica. 98 (3): 224–233. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.05.002. PMID 16750811.

Further reading

- Barracco, Margherita Anna; Steil, Ana Angélica; Gargioni, Rogério (1993). "Morphological characterization of the hemocytes of the pulmonate snail Biomphalaria tenagophila". Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 88 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1590/s0074-02761993000100012. PMID 8246758.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Biomphalaria tenagophila. |