Bengt Danielsson

Bengt Emmerik Danielsson (6 July 1921 – 4 July 1997) was a Swedish anthropologist, writer, and a crew member on the Kon-Tiki raft expedition from South America to French Polynesia in 1947. In 1991, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award for "exposing the tragic results of and advocating an end to French nuclear colonialism."

Bengt Danielsson | |

|---|---|

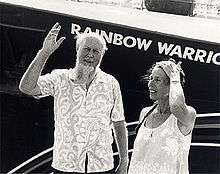

Bengt (left) and his wife, Marie-Thérèse Danielsson | |

| Born | July 6, 1921 Krokek, Sweden |

| Died | July 4, 1997 (aged 75) Stockholm, Sweden |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Alma mater | Uppsala University |

| Occupation | Anthropologist Writer |

| Employer | National Museum of Ethnology (Sweden) |

| Known for | Crew member on the Kon-Tiki Right Livelihood Award (1991) |

| Spouse(s) | Marie-Thérèse Danielsson ( m. 1948–1997) |

| Children | Maruia (1952–1972) |

Biography

Danielsson was born in Krokek, Sweden and was the son of chief physician Emmerik Danielsson (1875–1927) and Greta, née Källgren (1889–1990). His father died in a traffic accident when he was six years old, and after that Danielsson grew up in Norrköping with his mother and aunt, who were women that encouraged his adventuring ambitions.[1][2] He obtained a Doctor of Licentiate from Uppsala University in 1954 and a Doctor of Philosophy in anthropology in 1955.[3] Danielsson was intendant at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii from 1952 to 1966. Danielsson was Swedish consul in French Polynesia from 1961 to 1978 and extra museum director of Sweden's National Museum of Ethnology from 1966 to 1971. He was also correspondent for the Pacific Islands Monthly.[1]

He participated in the Swedish-Finish Amazon Expedition 1946-47, the Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, Tuamotu Expedition 1949-51, the Pacific Science Board Expedition in 1952, Expedition to western Polynesia in 1953, Around Australia 1955-56, Vanderbilt Foundation expedition to the Society Islands in 1957 and Sveriges Radio's TV expedition to the South Pacific Ocean in 1962.[1]

After the Kon-Tiki expedition, Danielsson married in Lima in 1948, a French woman, Marie-Thérèse Sailley (1923–2003), daughter of factory owner Abel Sailley and Josephine, née Mayer.[1] They decided to settle in Raroia, the atoll on which the raft had made landfall.[4] They stayed there from 1949 to 1952, and in 1953 they moved to Tahiti. His doctoral thesis on the Tuamotus island chain, submitted to Uppsala University in 1955, was published the following year as Work and Life on Raroia.[5] He subsequently wrote many books and scripted many films, becoming one of the world's foremost students of Polynesia. He and his wife were particularly outspoken critics of French nuclear tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls, and of the destruction of Polynesian culture through colonialism.[4] Their daughter Maruia (1952–1972) died from cancer.[6]

Marie-Thérèse and Bengt Danielsson received the Right Livelihood Award for their campaigning work in 1991.[7] Bengt died in July 1997 following a deterioration in his health,[8] and was buried at Östra Tollstad Church in Mjölby Municipality, Sweden.[9]

Selected bibliography

- Danielsson, Bengt (1956). Work and Life on Raroia: An Acculturation Study from the Tuamotu Group, French Oceania. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

- Danielsson, Bengt (1962). What Happened on the Bounty. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

- Danielsson, Bengt (1965). Love in the South Seas. New York: Reynal.

- Danielsson, Bengt (1965). Gauguin in the South Seas. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

- Danielsson, Bengt & Marie-Thérèse (1977). Moruroa mon amour. London: Harmondsworth, Penguin.

- Danielsson, Bengt & Marie-Thérèse (1986). Poisoned Reign: French Nuclear Colonialism in the Pacific. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-008130-5.

References

- Uddling, Hans; Paabo, Katrin, eds. (1992). Vem är det: svensk biografisk handbok. 1993 [Who is it: Swedish biographical handbook. 1993] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedt. p. 233. ISBN 91-1-914072-X.

- "Ansedel Bengt Emmerik Danielsson" [Pedigree chart Bengt Emmerik Danielsson] (in Swedish). Gammalkilshembygdsforening.se. 2015-04-26. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- Åhlén, Agneta; Fries, Carl-Thore; Åhlén, Bengt, eds. (1959). Svenskt författarlexikon: biobibliografisk handbok till Sveriges moderna litteratur. [3], 1951-1955 [Swedish Writers dictionaries: Bio-bibliographic guide to Sweden's modern literature. [3], 1951-1955] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. p. 81.

- Cormick, Craig (29 January 1992). "Danielssons awarded alternative peace prize". Green Left. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "In Memoriam: Bengt Danielsson" (PDF). Newsletter #99, Association for Social Anthropology in Oceania. December 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-19. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-11-04. Retrieved 2010-01-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Marie-Thérèse and Bengt Danielsson". The Right Livelihood Award. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- "Marie-Thérèse and Bengt Danielsson (Polynesia)". Right Livelihood Award. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-04-30. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Bengt Danielsson" (in Swedish). Gravar.se. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

.jpg)