Battle of the Riachuelo

The Battle of the Riachuelo was a large and decisive naval battle of the Paraguayan War fought between Paraguay and the Empire of Brazil. By late 1864, Paraguay had scored a series of victories in the war; on June 11, 1865, however, its naval defeat by the Brazilian Empire on the Paraná River began to turn the tide in favor of the allies.[3]

| Battle of the Riachuelo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Paraguayan War | |||||||

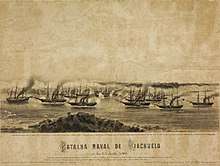

The Battle of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

It was the biggest naval battle fought between two South American countries.

Battle plan

The Paraguayan fleet was a fraction of the size of Brazil's, even before the battle. It arrived at the Fortress of Humaitá on the morning of June the 9th. Paraguayan dictator Francisco Solano López prepared to attack at Riachuelo the ships supporting allied land troops. Nine ships and seven cannon-carrying barges, totaling 44 guns,[4] plus 22 guns and two Congreve rocket batteries from river bank located troops, attacked the Brazilian squadron, nine ships with a total of 68 guns.[4] The Paraguayans had planned a surprise strike before sunrise since they were fully aware that the gross of Imperial Brazilian troops would offboard their steamers in order to sleep on land, leaving thus a small garrison of men to guard and watch their fleet. The original plan had been that, under the dark of the night, the Paraguayan steamers would sneak up to the docked Brazilian vessels and board them outright.[5][4] No confrontation other than the one carried out by the boarding party was planned, and the Paraguayan steamers were only there to provide cover from the inland battling forces.

Description of battle

The Paraguayan fleet left the fortress of Humaitá on the night of June 10, 1865, headed to the port of Corrientes. López had given specific orders that they should stealthily approach the docked Brazilian steamers before sunrise and board them, thus leaving the Brazilian ground forces bereft of their navy early on during the war.[5] For this, López sent nine steamers: Tacuarí, Ygureí, Marqués de Olinda, Paraguarí, Salto Guairá, Rio Apa, Yporá, Pirabebé and Yberá; under the command of Captain Meza who was aboard the Tacuarí.[5] However, some two leagues after leaving Humaitá, upon reaching a point known as Nuatá-pytá, the engine of the Yberá broke down.[6][7] After losing some hours in an attempt to fix it, it was decided to continue with only the remaining 8 steamers.[1]

The fleet arrived at Corrientes after sunrise, however, due to a dense fog, the plan was still executable since most, if not all, Brazilian forces were still on land.[6] However, not following López' orders, Captain Meza ordered that instead of approaching and boarding the docked steamers, the fleet was to continue down the river and fire at the camp and docked vessels as they passed by.[6][3] The Paraguayans opened fire at 9:25 am.[4]

The Paraguayans passed in a line parallel to the Brazilian fleet and continued downstream. Upon Captain Meza's order, the entire fleet opened fire on the docked Brazilian steamers.[6] The land troops hastily, upon realization that they were under attack, boarded their own ships and began returning fire. One of the Paraguayan steamers was hit in the boiler and one of the "chatas" (barges) was damaged as well.[1] Once out of range, they turned upstream and anchored the barges, forming a line in a very narrow part of the river. This was intended to trap the Brazilian fleet.[1]

Admiral Barroso noticed the Paraguayan tactic and turned down the stream to go after the Paraguayans. However, the Paraguayans started to fire from the shore into the lead ship, Belmonte. The second ship in the line, Jequitinhonha, mistakenly turned upstream and was followed by the whole fleet,[3] thus leaving Belmonte alone to receive the full firepower of the Paraguayan fleet, which soon put it out of action. Jequitinhonha ran aground after the turn, becoming an easy prey for the Paraguayans.[4]

Admiral Barroso, on board the steamer Amazonas, trying to avoid chaos and reorganize the Brazilian fleet, decided to lead the fleet downstream again and fight the Paraguayans in order to prevent their escape, rather than save Amazonas. Four steamers (Beberibe, Iguatemi, Mearim and Araguari) followed Amazonas. The Paraguayan admiral (Meza) left his position and attacked the Brazilian line, sending three ships after Araguari. Parnaíba remained near Jequitinhonha and was also attacked by three ships that were trying to board it. The Brazilian line was effectively cut in two. Inside Parnaíba a ferocious battle was taking place when the Marquez de Olinda joined the attackers.

Barroso, at this time heading upstream, decided to turn the tide of the battle with a desperate measure. The first ship that faced Amazonas was the Paraguarí which was rammed and put out of action.[8][4] Then he rammed Marquez de Olinda and Salto, and sank a "chata".[1] At this point Paraguari was already out of action. Therefore, the Paraguayans tried to disengage. Beberibe and Araguari pursued the Paraguayans, heavily damaging Tacuary and the Pirabebé, but nightfall prevented the sinking of these ships.

Jequitinhonha had to be put afire by Paraguari and Marquez de Olinda. In the end, the Paraguayans lost four steamers and all of their "chatas", while the Brazilians only lost the Jequitinhonha, coincidentally the ship responsible for the confusion.

Aftermath and consequences

After the battle, the eight remaining Brazilian steamers sailed down river.[9] President López ordered Major José Maria Brúguez with his batteries to quickly move inland to the south to wait for and attack the passing Brazilian fleet. So the fleet had to run the gauntlet. On August 12, Brúguez attacked the fleet from the high cliffs at Cuevas. Every Brazilian ship was hit, and 21 men were killed.[10]

The Paraguarí, which had been rammed by the Amazonas, was set ablaze by the Brazilians; however, the ship had a metal hull. A few months later, López ordered the Yporá to retrieve the hull, tow it to the Jejui River and sink it there.[8] Also, under orders from López, one month after the battle, the Yporá returned to the scene and, again under the cover of the night and stealthily so as to not alarm another Brazilian steamer which was in the location, boarded the remains of the Jequitinhonha and stole one of its cannons.[8]

Meza was wounded by a gunshot to the chest on June 11, during the battle.[1] While he did leave the battle alive, he would die eight days later from this wound while at the Humaitá hospital. López, who upon learning of Meza's death said "Si no hubiera muerto con una bala, debia morir con cuatro[8]" (Had he not died from one gunshot, he would have to die from four), gave orders for no officers to attend his burial.

Manuel Trujillo, one of the Paraguayan soldiers that took part in the Riachuelo battle recalls "When we sailed down river on full steam, passing all the Brazilian steamers on the morning of the eleventh, we were all shocked since we knew that all we had to do was approach the steamers and 'all aboard!'".[8] He also recalls that, during the battle, the land troops who had been taken on the steamers in order to board the Brazilian fleet were shouting "Let's approach the steamers! We came in order to board them and not to be killed on deck!".[8]

Barroso had turned the tables by creatively ramming the enemy ships. The Brazilian navy won a decisive battle. General Robles was effectively stopped in Rio Santa Lúcia. The threat to Argentina was neutralized.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Riachuelo. |

Order of battle

Brazil

| Unit[4][7] | Type | Tonnage | Horsepower | Firepower | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazonas | Frigate | 1050 | 300 | 1 70 lb and 5 68 lb | Flagship – paddle steamer |

| Belmonte | Corvette | 602 | 120 | 1 70 lb, 3 68 lb and 4 32 lb | |

| Jequitinhonha | Corvette | 647 | 130 | 2 68 lb and 5 32 lb | |

| Beberibe | Corvette | 637 | 130 | 1 68 lb and 6 32 lb | |

| Parnaíba | Corvette | 602 | 120 | 1 70 Lb, 2 68 lb and 4 32 lb | |

| Ipiranga | Gunboat | 325 | 70 | 7 30 lb | |

| Araguari | Gunboat | 415 | 80 | 2 68 lb and 2 32 lb | |

| Iguatemi | Gunboat | 406 | 80 | 3 68 lb and 2 32 lb | |

| Mearim | Gunboat | 415 | 100 | 3 68 lb and 4 32 lb |

Paraguay

| Unit[1][4][11] | Type | Tonnage | Horsepower | Firepower | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacuarí | Corvette | 620 | 120 | 2 68 lb and 6 32 lb | |

| Ygureí | Steamboat | 650 | 130 | 3 68 lb and 4 32 lb | |

| Marquez de Olinda | Steamboat | 300 | 80 | 4 18 lb | Captured from Brazil earlier in the war |

| Salto Guairá | Steamboat | 300 | 70 | 4 18 lb | |

| Paraguarí | Corvette | 730 | 130 | 2 68 lb and 6 32 lb | |

| Yporá | Steamboat | 300 | 80 | 4 guns | Gun rates unavailable. Scuttled in the River Yhaguy after the battle. Boiler, crankshaft and paddle wheel on display |

| Yberá | Steamboat | 300 | 4 guns | ||

| Pirabebé | Steamboat | 150 | 60 | 1 18 lb | Scuttled in the River Yhaguy after the battle. Wreckage restored and today on public display |

| Rio Apa | |||||

| 2 Chatas | 40 | 1 80 lb gun each | Barges – Towed | ||

| 5 Chatas | 35 | 1 68 lb each | Barges – Towed | ||

| Shore troops | 22 32 lb and two congreve batteries | Shore troops |

Gallery

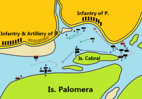

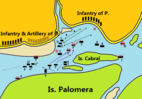

Place where the battle was fought.

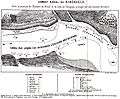

Place where the battle was fought.- Plan of the battle in portuguese.

Plan of the battle in french.

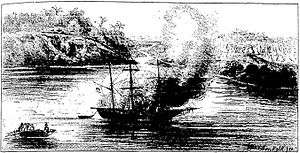

Plan of the battle in french. The Jequitinhonha (left) trapped on a sandbar during the Battle of Riachuelo.

The Jequitinhonha (left) trapped on a sandbar during the Battle of Riachuelo.

_incendiando_o_vapor_inimigo_%E2%80%94_Paraguay_%E2%80%94_debaixo_do_fogo_das_baterias_paraguayas_do_Riachuelo.jpg)

._-_D'apr%C3%A8s_un_dessin_envoy%C3%A9_par_M._F%C3%A9lix_Vogeli.jpg)

- The Brazilian corvette Amazonas rams and sinks the Paraguayan Jejuy.

.jpeg)

_(De_una_l%C3%A1mina_litogr%C3%A1fica_impresa_en_el_Brasil).jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_Mearim_(com._Barboza)%2C_Araguary_(com._Hoonholtz)_e_Iguatemy_(com._Coimbra)%2C_trabalhando_em_desencalhar_o_Jequitinhonha.jpg) The Ypiranga, Mearim, Araguary and Iguatemy trying to refloat the Jequitinhonha.

The Ypiranga, Mearim, Araguary and Iguatemy trying to refloat the Jequitinhonha. The Jequitinhonha ran under the batteries of the strong enemies, having to be left by the crew. Not being able to get away from the beach, it was burned by the crew.

The Jequitinhonha ran under the batteries of the strong enemies, having to be left by the crew. Not being able to get away from the beach, it was burned by the crew.

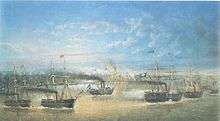

Combat of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles.

Combat of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles. The Battle of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles.

The Battle of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles.

References

Notes

- Charles Ames Washburn (1871). The History of Paraguay: With Notes of Personal Observations, and Reminiscences of Diplomacy Under Difficulties. Lee & Shepard. pp. 66-73.

- Hooker, T.D., 2008, The Paraguayan War, Nottingham: Foundry Books, ISBN 1901543153

- R. G. Grant (2017-10-24). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. Book Sales. pp. 641–. ISBN 978-0-7858-3553-0.

- Thomas Whigham (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and early conduct. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 308–326. ISBN 0-8032-4786-9.

- Bareiro Saguier & Villagra Marsal 2007, p. 69.

- Bareiro Saguier & Villagra Marsal 2007, p. 70.

- James Hamilton Tomb (2005). Engineer in Gray: Memoirs of Chief Engineer James H. Tomb, CSN. McFarland. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7864-1991-3.

- Bareiro Saguier & Villagra Marsal 2007, p. 71.

- Bareiro Saguier & Villagra Marsal 2007, p. 72.

- Leuchars, Chris, To the Bitter End: Paraguay and the War of Triple Alliance, Greenwood Press, 2002, p.86

- Hernâni Donato (1996). Dicionário das batalhas brasileiras. IBRASA. pp. 440–. ISBN 978-85-348-0034-1. Different sources provide different names for the Paraguayan ships

Sources

- Bareiro Saguier, Ruben; Villagra Marsal, Carlos (2007). Testimonios de la Guerra Grande. Muerte del Mariscal López. Tomo II. Asuncion, Paraguay: Editorial Servilibro.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Riachuelo". The South American Military History Webpage. Archived from the original on 2005-03-28. Retrieved December 15, 2005. – by Ulysses Narciso

- Fragoso, Augusto Tasso. História da Guerra entre a Tríplice Aliança e o Paraguai, Vol II. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa do Estado Maior do Exército, 1934.

- Schneider, L. A guerra da tríplice Aliança, Tomo I. São Paulo: Edições Cultura, 1945.