Battle of the Coconut Grove

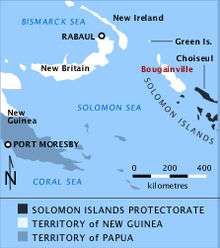

The Battle of the Coconut Grove was a battle between United States Marine Corps and Imperial Japanese Army forces on Bougainville. The battle took place on 13–14 November 1943 during the Bougainville campaign, coming in the wake of a successful landing around Cape Torokina at the start of November, as part of the advance towards Rabaul as part of Operation Cartwheel.

| Battle of the Coconut Grove | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bougainville campaign in the Pacific Theater (World War II) | |||||||

Marines advance into the Coconut Grove with tank support | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Allen H. Turnage | Harukichi Hyakutake | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 21st Marine Regiment | 23rd Infantry Regiment | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

20 dead 39 wounded | U.S. estimate: 40 killed | ||||||

In the days following the landing, several actions were fought around the beachhead at Koromokina Lagoon and along the Piva Trail. As the beachhead was secured, a small reconnaissance party pushed forward and began identifying sites for airfield construction outside the perimeter. To allow construction to begin, elements of the 21st Marine Regiment were ordered to clear the Numa Numa Trail. They were subsequently ambushed by a Japanese force and over the course two days a pitched battle was fought. As the Marines brought up reinforcements, the Japanese withdrew. By the end of the fighting, the Marines had gained control of a tactically important intersection of the Numa Numa and East–West Trails. A further action was fought around Piva Forks in the days following the ambush.

Background

In early November, US forces had landed around Cape Torokina and established a beachhead, as part of Allied efforts to advance towards the main Japanese base around Rabaul, the isolation and reduction of which was a key objective of Operation Cartwheel.[1] A Japanese counter landing at Koromokina Lagoon was defeated in the days following the US landing, and the beachhead was subsequently secured.[2] Following this, a blocking force was pushed forward towards the Piva Trail, a key avenue of approach towards Cape Torokina, to defend the narrow beachhead while further supplies and reinforcements were landed.[3] The Japanese commander on Bougainville, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, ordered the 23rd Infantry Regiment to advance towards Cape Torokina from the main Japanese position around Buin.[4] Heavy fighting subsequently took place during the Battle for Piva Trail as the Japanese advancing from Buin clashed with the Marine blocking force. The battle resulted in the capture of Piva by US forces, after which a small reconnaissance party of naval construction personnel, escorted by a force of Marine infantrymen, was sent out in search of a site suitable for an airfield. Led by Commander William Painter, a Civil Engineer Corps officer, the party identified a suitable location about 1 mile (1.6 km) beyond the perimeter, about 3 miles (4.8 km) inland,[5] and they set about preparations for the construction of several landing strips for bomber and fighter aircraft.[6][7]

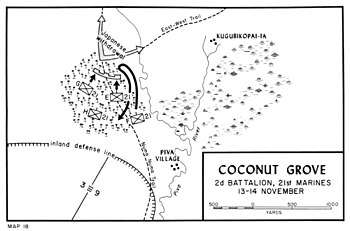

On 9 November, Painter returned to the main perimeter and the following day the combat patrol also returned, having clashed with a Japanese patrol. Further patrols were sent up the Piva Trail, advancing past a coconut grove that was near the intersection with the East–West Trail. These patrols failed to locate the Japanese.[6] The swamps in the area impeded supply and slowed movement. As a result, it was initially impossible for US forces to advance the perimeter of their beachhead far enough to cover the proposed airfield site selected by Painter. It was therefore decided to establish a strong outpost, capable of sustaining itself until the lines could be advanced to include it, at the junction of the Numa Numa and East–West Trails. This outpost would then be used to send out patrols to disrupt Japanese forces in the local area.[5] On the afternoon of 12 November, General Allen H. Turnage—commander of the 3rd Marine Division—directed the 21st Marine Regiment to send a company-sized patrol up the Numa Numa Trail. The company selected for the patrol was Company E, under Captain Sidney Altman.The patrol was to move up the Numa Numa Trail to its junction with the East–West Trail. From there, the company was to reconnoiter each trail for a distance of about 1,000 yd (910 m), to eventually set up an outpost in the area.[8] As these preparations were taking place, the Japanese, unbeknownst to the US commanders, had occupied a strong position around the coconut grove.[5]

Throughout the night of 12/13 November, the Marines' orders were modified to increase the size of the patrol to two companies, with a headquarters element and an artillery forward observer team to control fire support. It was also decided to expedite the establishment of the outpost at the junction of the East–West and Numa Numa Trails. In view of the importance of his assignment, Colonel Evans Ames—commander of the 21st Marines—sought divisional orders to send the entire 2nd Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Eustace Smoak. This request was subsequently granted,[9] thus enabling the US commander to maintain a company in reserve.[5] Orders were issued for the patrol to step off early on 13 November, with Company E leading out at 06:30. They were to move to an assembly area positioned to the rear of the front line held by the 9th Marine Regiment and wait for the rest of the battalion to arrive before continuing.[8][10]

Battle

While Company E waited for further orders in the assembly area the remainder of the 2nd Battalion, 21st Marines was supplied with rations, water and ammunition, and awaited the arrival of the artillery forward observer party. Due to further delays, at 07:30, Company E was ordered to advance up the Numa Numa Trail and begin to set up the outpost without the rest of the battalion, and at 08:00 proceeded up the trail without incident. Around 11:05, when the company had reached a point about 200 yd (180 m) south of its objective, it came under heavy fire from a Japanese ambush that included mortars and machine guns, as well as sniper fire from the trees. As casualties mounted, the company commander, Altman, dispatched a runner to find Smoak and inform him of the situation.[11][12]

The runner found Smoak with the rest of the battalion at 12:00. They were about 1,200 yd (1,100 m) south of the trail junction, having been delayed by the late arrival of the forward observer team. Their progress had been further delayed due to the swampy ground which had made it difficult to bring up supplies to the assembly area. In response to the news of the ambush, Smoak led the rest of the battalion down the trail as rapidly as possible to provide support to Company E. One platoon of Company F was left behind to provide security for the forward observer's wire team.[13]

By 12:45, the battalion was 200 yd (180 m) to the rear of Company E, whereupon Smoak learned that Company E was pinned down by heavy fire and was taking casualties and reinforcement was needed immediately. The Japanese ambush position was located south of the trail junction. Smoak promptly ordered forward Company G—under the command of Captain William McDonough—to reinforce Company E, while Major Edward Clark's Company H was ordered to provide 81 mm mortar support for the attack. Company F—led by Captain Robert Rapp—less the platoon protecting the wire team, was ordered into reserve and to await orders. The artillery forward observer's party was ordered to move forward under the command of Major Glenn Fissel, the battalion executive officer, to assess the situation and call in artillery concentrations to prevent the Japanese from maneuvering.[13]

Upon reaching Company E with the forward observer's party, Fissel observed that the greatest volume of fire was coming from the east side of the trail, in the direction of Piva River, promptly calling for an artillery concentration in that area. Receiving conflicting reports, to obtain more accurate information, Smoak pushed his command post forward into the edge of the coconut grove through which the Numa Numa Trail ran. Fissel was able to make contact with Smoak and advised that Company E needed help immediately. After a quick reconnaissance, Smoak ordered Company F to pass through Company E, resume the attack, and allow Company E to withdraw, reorganize, and take up a protective position on the battalion's right flank. Company G—which had reached a position to the left of Company E—was ordered to hold its position. Company F began its movement forward, and Company E—finding an opportunity to disengage itself—began a withdrawal, redeploying on the right of the battalion's position. Company F failed to make contact with either Company E or Company G.[13]

During the withdrawal, Fissel was wounded. Unable to determine the exact locations on the battalion's companies, Smoak sent several staff officers to determine the exact positions of his companies. Company F could not be found, and a large gap existed between the right flank of Company G and the left flank of Company E which left the battalion in a precarious position. As a result, Smoak ordered Company E to move forward, contact Company G, and establish a line to protect the battalion's front and right flank. In the meantime, Company G was to extend its line to the right to tie in with Company E. By 16:30, Smoak decided to dig in for the night, with his companies suffering fairly heavy casualties, Company F was missing and communications with regimental headquarters and the artillery had been broken.[13]

At 17:00, the gunnery sergeant of Company F reported in person to the battalion command post. Company F had moved out as ordered from its reserve position to the lines held by Company E, however, had veered too far to the right and had missed Company E entirely. Company F proceeded onward and found itself in a position behind the Japanese lines. It was reported by the gunnery sergeant that Rapp had found it increasingly difficult to control his company, suffering some casualties and platoons intermingling and becoming disorganized. The gunnery sergeant was ordered to go back to Company F and guide it back to the battalion position. By 17:45, Company F was back in the battalion lines and had taken a position on the perimeter which was set up for the night. At 18:30, communications were reestablished and the artillery of the 12th Marine Regiment was ordered establish pre-designated fire zones north, east, and west sides of the 2nd Battalion, 21st Marines' perimeter. The 2nd Marine Raiders Battalion—attached to the 21st Marine Regiment—was directed to protect the supply line from the main line of resistance to the 2nd Battalion, 21st Marines. Ames ordered Smoak to send out patrols and prepare to attack the Japanese positions in the morning, with tank, artillery, and aircraft support.[14]

Throughout the night, the Japanese defenders fired their rifles sporadically, but made no attempt to assault the Marine positions.[15] On the morning of 14 November, all companies established outposts about 75 yd (69 m) in front of the perimeter, and sent out patrols. At 09:05, airstrikes were called in, with 18 TBF Avengers from VMTB-143 bombing and strafing the area after artillery marked the target with smoke. Immediately after the airstrike, Company E moved back into its original position in the line. Smoak then ordered an attack, with Company E on the left and Company G on the right while Companies F and H would hold in reserve. The attack was to be a frontal assault, supported by five M3 Stuart tanks of the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 3rd Tank Battalion.[16]

The attack was set for 11:00; however, due to communications being cut at 10:45, the attack was ordered delayed until communications had been re-established. The communications were reestablished at 11:15 and the attack proposed at 11:55. The 2nd Battalion, 12th Marine Regiment—in direct support—was to provide a 20-minute preparation followed by a rolling barrage. After the preparatory barrage, the attack commenced at 11:55. The Japanese immediately reoccupied their positions and opened fire with rifles and machine guns. Several tanks of 3rd Tank Battalion became confused and fired into the Marines on their flank,[17] and accidentally ran over several men.[18] Two tanks were damaged by anti-tank fire and mines.[12] At this time, fire control among the Marines broke down and they began shooting wildly for about five minutes until Smoak came forward to reorganize the troops, personally ordering the Marines to cease fire and to halt the advance. Japanese fire having stopped, all companies were directed to stand fast in the positions where they found themselves and to send out patrols to a distance 100 yd (91 m) north of the trail junction.[19]

The supporting tanks—except the two that had been damaged—were ordered to return to an assembly position in reserve. At this time, it was discovered that the Marines had overrun the Japanese positions, although there were still some defenders alive in the dugouts. Riflemen with grenades quickly dealt with these and by 14:00, all Japanese resistance had been overcome, and patrols returned reporting no further contact. At 14:15, the advance was resumed, with mopping up operations commencing. However, the Japanese troops managed to successfully break contact and began withdrawing to the east. By 15:30 to 15:45 the Marines had occupied their objective, with a perimeter defense organized for the night.[20][21]

Aftermath

In the aftermath, US forces estimated that they had come up against a Japanese force of around company strength. The Japanese positions were very extensive and well organized, with numerous machine gun positions and many dugouts that were deep with good overhead cover. Although a careful count of Japanese dead was not taken,[20] at least 40 Japanese bodies were recovered.[21] Six Japanese machine guns were captured. The Marine forces lost 20 killed, including five officers, and 39 wounded.[20] Although not provided for in the first phase of the battle when Company E advanced up the trail,[22] artillery preparation was later recognized as of prime importance against the Japanese system of defenses, with their well dug-in, concealed, and covered foxholes, equipped with a high percentage of automatic weapons, in turn covered by equally invisible riflemen in trees and spider-hole. Without strong fire support, severe losses would have been sustained by the attacking Marines.[17]

The fighting ended with the Marines gaining control of the important junction between the Numa Numa and East–West Trails.[23] This set the conditions for US forces to begin an advance on all fronts commencing on 15 November, extending the perimeter of the Torokina beachhead to about 1,000 yd (910 m) on the left (west) flank and about 1,500 yd (1,400 m) north in the center, to the inland defense line known as "Dog".[20] This enabled construction of the Piva airfields to begin; meanwhile, further supplies were landed around Cape Torokina as the beachhead was further consolidated.[24] A few days after the fighting around the Coconut Grove, the Battle of Piva Forks, the final major action around the Torokina beachhead for 1943, was fought.[25] While minor actions were also fought around Hellzapoppin Ridge and Hill 600A in December,[26] the fighting around Bougainville largely died down until March 1944 when the Japanese launched a large-scale assault on Torokina.[27]

Citations

- Miller 1959, pp. 222–225.

- Morison 1958, pp. 341 & 347.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 236.

- Miller 1959, p. 259.

- Gailey 2013, p. 102.

- Rentz 1946, p. 54.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 241.

- Rentz 1946, pp. 54–55.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 241–242.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 242.

- Rentz 1946, pp. 55–56.

- Gailey 2013, p. 103.

- Rentz 1946, p. 56.

- Rentz 1946, p. 57.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 243.

- Rentz 1946, pp. 57–58.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 244.

- Chapin 1997, p. 17.

- Rentz 1946, p. 58.

- Rentz 1946, p. 59.

- Gailey 2013, p. 104.

- Rentz 1946, p. 55.

- Morison 1958, p. 348.

- Chapin 1997, pp. 17–18.

- Morison 1958, p. 352

- Rentz 1946, pp. 83–87.

- Tanaka 1980, pp. 73 & 255–275

References

![]()

- Chapin, John C. (1997). Top of the Ladder: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons. World War II Commemorative series. Washington, DC: Marine Corps History and Museums Division. OCLC 38258412.

- Gailey, Harry A. (2013) [1991]. Bougainville, 1943–1945: The Forgotten Campaign. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81314-344-6.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 63151382.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 6. Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1307-1.

- Rentz, John M. (1946). Bougainville and the Northern Solomons. USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006.

- Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.