Battle for Piva Trail

The Battle for Piva Trail was a battle between United States Marine Corps and Imperial Japanese Army forces on Bougainville Island. The battle took place on 8–9 November 1943 during the Bougainville campaign in the days following the US landing at Cape Torokina earlier in the month.

The fighting took place inland from the US beachhead, as the Japanese began moving troops from the 23rd Infantry Regiment north from southern Bougainville. These troops subsequently clashed with a blocking force of US Marines that had been positioned along the Piva Trail to protect one of the key avenues of approach towards Cape Torokina. It had been intended that the 23rd Infantry Regiment would co-ordinate their assault with a counter landing at Koromokina Lagoon, but ultimately this did not occur as the main assault was delayed until after the counter landing was defeated. The fighting for the Piva Trail resulted in heavy casualties for the Japanese and was followed by a series of actions throughout November and December 1943 as US forces sought to expand their perimeter around Cape Torokina.

Background

In early November, US forces had landed around Cape Torokina and established a beachhead, as part of Allied efforts to advance towards the main Japanese base around Rabaul, the isolation and reduction of which was a key objective of Operation Cartwheel.[2] Facing the American beachhead at Cape Torokina were troops of the Japanese 17th Army, commanded by General Harukichi Hyakutake, the main elements of which were drawn from Lieutenant General Masatane Kanda's 6th Division.[3] In response, the Japanese attempted a counter landing at Koromokina Lagoon, and began moving reinforcements north from southern Bougainville.[4]

To protect the narrow beachhead while further reinforcements and supplies arrived, the U.S. 2nd Marine Raider Battalion advanced inland and set up a roadblock on the Piva Trail, around the junction with the Numa–Numa Trail,[5] one of the key avenues of approach towards Cape Torokina. In an effort to reinforce the troops landing around Koromokina Lagoon, the Japanese 23rd Infantry Regiment, advancing from southern Bougainville, was tasked with dislodging the US troops holding the Piva Trail.[6] The Japanese intent had been to co-ordinate actions on both sides of the US perimeter, but ultimately the landing around Koromokina Lagoon was defeated before the 23rd Infantry Regiment could mount a full-scale attack against the Marine defenses along the Piva Trail.[7]

Battle

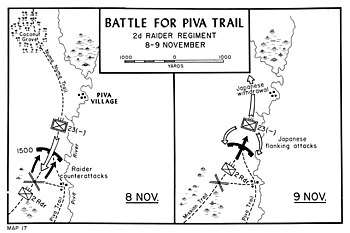

On the night of 5–6 November, the Marines drove off two preliminary attacks from the Japanese 23rd Infantry Regiment.[8] Colonel Edward A. Craig, commander of the 9th Marines to which 2nd Raider Battalion was attached,[9] surmised that this was just a preparatory action and brought up more Raiders to reinforce the roadblock. When the Japanese attacked the following afternoon (7 November), the Marines were ready and drove the Japanese back to Piva village. Early on the morning of 8 November, Major General Shun Iwasa, commander of the Japanese 6th Division's infantry group (the Iwasa Detachment),[10] renewed the attack with two full battalions. The Americans brought up men of the 3rd Raider Battalion to protect the flanks of the Marines already engaged, as well as some light tanks. Frontal attacks by the Japanese were repulsed.[11]

Major General Allen H. Turnage, in command of the 3rd Marine Division, determined that the Japanese lodged on the trail represented a threat to the airstrips and had to be removed, with the assault beginning on the morning of 9 November. The Japanese had several well-placed machine guns and were attempting an attack of their own; a bloody stalemate developed. Private First Class Henry Gurke of the 3rd Marine Raider Battalion was awarded the second Medal of Honor of the Bougainville Campaign during this fight by throwing himself on a grenade and saving his foxhole-mate.[12] Marine firepower eventually proved too much for the Japanese, who retreated to and through Piva Village in the early and mid-afternoon. The Marines took possession of the vital intersection of the Piva and Numa Numa Trails.[13]

On 10 November, an air strike consisting of 12 Avenger torpedo bombers attacked Japanese positions in front of the Marines along the Numa-Numa Trail. Around 10:00 hours, the Marines began to advance towards the village, supported by artillery.[14] The movement was unopposed and large amounts of equipment and dead bodies were found around the abandoned Japanese positions. Two battalions of the 9th Marine Regiment subsequently followed them up and occupied Piva village just after 13:00 hours. As the beachhead around Cape Torokina was expanded, the 9th Marines managed to link up with the 3rd Marines on their left. Meanwhile, the 2nd Raider Battalion was relieved and moved back into a reserve position.[15]

Aftermath

Casualties during the fighting for Piva Trail were heavy. It is estimated that the Japanese may have lost up to 550 killed,[16] with 125 being killed on the first day and over 140 killed on the second day.[1] The Marines lost 20 killed and 57 wounded over the course of both days.[1] In the aftermath, US forces began expanding the perimeter around the beachhead, systematically advancing to several inland defense lines. A reconnaissance patrol subsequently advanced up the Numa–Numa Trail and identified several sites for airfields beyond the beachhead. The 21st Marines were dispatched to advance up the Numa–Numa Trail to clear the area for construction to begin. They were subsequently ambushed, resulting in the Battle of the Coconut Grove on 13–14 November.[17] A further action would be fought around Piva Forks in late November.[18]

Meanwhile, further reinforcements and supplies were landed at Cape Torokina, and US Army forces began arriving to reinforce the Marines. In late December work on the airfields was complete and aerial bombing raids began against the Japanese base around Rabaul, while minelaying aircraft interdicted Japanese sea lanes of communication through the Buka Passage.[19] Having initially held back forces to reinforce northern Bougainville, as the Japanese high command realized that the Cape Torokina lodgment was not a ruse, and would not be followed by a further assault on Buka, they slowly began moving troops from southern Bougainville, landing in small numbers around Empress Augusta Bay throughout late December. Meanwhile, several air attacks were launched on the US perimeter, while artillery was moved up and began shelling the perimeter from Hellzapoppin Ridge and Hill 600A. In late December, these features became the scene of further fighting as the 21st Marine Regiment was ordered to capture the Japanese positions.[20] After this, there was a lull in the fighting on Bougainville as the Japanese decided to delay plans to launch a concerted counterattack, postponing the assault on Torokina until March 1944.[21]

Notes

- Gailey 1991, p. 101

- Miller 1959, pp. 222–225.

- Miller 1958, p. 238.

- Morison 1958, p. 341.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 236.

- Miller 1959, p. 260; Morison 1958, p. 347

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 236; Morison 1958, p. 347.

- Morison 1958, p. 347

- Rentz 1946, p. 48; Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 236.

- Tanaka 1980, p. 255; Miller 1959, p. 259.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 237–240

- Chapin 1997, p. 16

- Gailey 1991, pp. 99–101

- Morison 1958, p. 347.

- Shaw & Kane 1963, p. 240.

- Chapin 1997, pp. 14–17; Clark 2006, p. 108

- Morison 1958, pp. 347–348

- Rentz 1946, pp. 39–40; Shaw & Kane 1963, pp. 247–267

- Morison 1958, pp. 348–349.

- Morison 1958, pp. 348–349, 362–363.

- Tanaka 1980, pp. 73 & 255–275

References

- Chapin, John C. (1997). Top of the Ladder: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons. World War II Commemorative Series. Marine Corps History and Museums Division. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- Clark, George B. (2006). The Six Marine Divisions in the Pacific: Every Campaign of World War II. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78642-769-7.

- Gailey, Harry A. (1991). Bougainville, 1943–1945: The Forgotten Campaign. Lexington, Kentucky, USA: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9047-9.

- Miller, John, Jr. (1959). Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army. OCLC 63151382.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 6. Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1307-1.

- Rentz, John M. (1946). Bougainville and the Northern Solomons. USMC Historical Monograph. Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Kane, Douglas T. (1963). Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on 20 November 2006.

- Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.