Battle of Oivi–Gorari

The Battle of Oivi–Gorari (4–11 November 1942) was the final major battle of the Kokoda Track campaign before the Battle of Buna–Gona. Following the capture of Kokoda by Australian forces on 2 November, the Allies began flying in fresh supplies of ammunition and food to ease the supply problems that had slowed their advance north after the climactic battle around Ioribaiwa, which coupled with reverses elsewhere, had stopped the Japanese advance on Port Moresby.

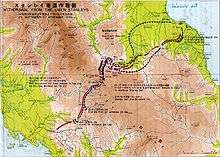

On 4 November, the Australians resumed their advance, pushing towards Oivi along the Kokoda–Sanananda Track. Around the high ground at Oivi, the lead Australian element, the 16th Brigade, came up against well entrenched Japanese defenders from the South Seas Detachment who were intent on stalling the Australian advance towards the sea. Over the course of several days, determined resistance held off a number of frontal assaults, forcing the commander of the 7th Division, Major General George Vasey, to attempt a flanking move to the south. A second brigade, the 25th Brigade, subsequently bypassed Oivi via a parallel track before turning north and attacking the depth position around Gorari. Hand-to-hand fighting resulted in heavy casualties on both sides before the Japanese withdrew east and crossed the flood-swollen Kumusi River, where many drowned and a large quantity of artillery had to be abandoned.

Background

On 21 July 1942, Japanese forces landed on the northern Papuan coast around Buna and Gona, as part of a plan to capture the strategically important town of Port Moresby via an overland advance along the Kokoda Track following the failure of a seaborne assault during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May.[1] During the next three months, the Australians fought a series of delaying actions along the Kokoda Track, as the Japanese had advanced steadily south towards Port Moresby. Following reverses around Milne Bay and Guadalcanal,[2] and a climactic battle around Ioribaiwa, in early September the Japanese reached the limits of their supply line and were ordered to assume a defensive posture until conditions became more favourable for a renewed effort on Port Moresby.[3][4] They subsequently began falling back north over the mountains of the Owen Stanley Range.[5][6]

Throughout October, the Australians, supported by US air assets which were heavily bombing Japanese lines of communication,[7] had sought to wrest control of the campaign, and significant actions were fought around Templeton's Crossing and Eora Creek as the Australians went on the offensive.[8] Progress was slow, and in the aftermath, the Australian high command relieved Major General Arthur Allen of his command, replacing him with Major General George Vasey.[9] Finally, on 2 November Kokoda was secured by the troops from Brigadier Kenneth Eather's 25th Brigade.[10] The recapture of Kokoda provided the Allies with a forward airfield into which supplies could be flown, helping to ease the resupply issues that had slowed the Allied pursuit up to that point, with supplies of ammunition and food greatly improving the situation for the Allied troops[11] and enabling soldiers who had been pressed into portage tasks carrying supplies up the track, to be re-allocated to combat duties.[12] The forward airfield also greatly reduced the time taken to evacuate casualties to Port Moresby, greatly improving a wounded soldier's chances of survival.[13]

Battle

Following a brief pause to resupply with air drops occurring around Kobara,[14] on 4 November 1942, the Australian advance continued after securing Kokoda, carried by Vasey's 7th Division, with Brigadier John Lloyd's 16th Brigade, which had come up from Alola and bypassed Kokoda, assuming the lead from the 25th Brigade. Setting out from Kobara, they advanced north towards Pirivi, before striking east towards Oivi.[15] Out of the mountains, and amidst the heat of the more open low land countryside, the advance was slow. Nevertheless, the Australians pushed forward along the narrower north–south track that ran between Kokoda and Sanananda,[13] until they were halted along the high ground around Oivi by a strongly entrenched Japanese force.[11] In the fighting that ensued, the two Australian brigades – Lloyd's 16th and Eather's 25th – consisting of 3,700 men,[13] engaged the remnants of the Japanese 41st Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Kiyomi Yazawa, and 144th Infantry Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto Hiroshi. Together these regiments formed the South Seas Detachment (Nankai Shintai), a 2,800-strong formation under the command of General Tomitaro Horii,[13] supported by 15 mountain guns from the 55th Mountain Artillery Regiment and 30 heavy machine guns. Camouflaged and strengthened with palm logs, with interlocking fields of fire and snipers in rubber and palm trees,[16] the positions were well established, having been constructed over several weeks and the Japanese defenders were determined to make a stand.[13] The Australians, who had lacked artillery for most of the campaign, were buoyed by the plentiful supply of mortar rounds due to the proximity of the landing strip at Kokoda.[17]

.jpg)

Several frontal assaults by the 16th Brigade, the lead Australian brigade, around Oivi were repulsed over several days with the Australians being subjected to heavy artillery fire,[13] until the Australian divisional commander, Vasey, decided to launch a flanking move towards Gorari, determining that in the circumstances he could afford move the 25th Brigade forward from Kokoda, leaving it largely undefended.[18] After stockpiling stores, the attack was commenced.[11] Two battalions – the 2/2nd and 2/3rd Infantry Battalions, as well as the Militia 3rd Infantry Battalion – pinned the Japanese defenders in place around Oivi, while the 2/1st, detached from the 16th, carried out a flanking move with the three battalions of the 25th Brigade – the 2/25th, 2/31st and 2/33rd Infantry Battalions – which were sent on a wide flanking move around Gorari by way of Kobara and Komondo.[19][11][20]

Advancing east along a track that ran parallel to the south of the Kokoda–Sananada Track, on 6 November, the 2/1st outflanked Oivi, seeking a lateral track to take them north towards Gorari at Waju. Initially, this was missed in the thick jungle, and the battalion was delayed a day as it had to turn back west to regain its bearings. Once they had located the track on 7 November, the 2/1st was joined by the rest of the 25th Brigade and they began advancing north. In response, the Japanese sent the II and III Battalions of the 144th Regiment south from Gorari to Baribe, halfway along the Waju–Gorari Track, to form a blocking position while on 8 November, as the 41st Infantry Regiment came under heavily aerial bombardment and strafing from US aircraft around Oivi,[21] the I Battalion of the 144th withdrew from Oivi where it had been supporting the 41st, to protect Gorari.[13]

On 9 November, two Australian battalions began surrounding the Japanese around Baribe, while two other battalions bypassed the position and continued on towards Gorari.[13] Heavy hand-to-hand fighting ensued,[11] as the 2/31st and 2/25th fought around Baribe, while the 2/33rd invested Gorari from the west and the 2/1st attacked from the east and clashed with Horii's headquarters.[13] Elements of the 2/31st also pushed around the 2/1st to cut the track further east on 11 November.[22] As the pincer movement threatened to encircle the Japanese defenders around Oivi who were running low on ammunition and who were weak from lack of food, Horii gave the order for them to withdraw. During the evening of 11/12 November, the remnants of the Japanese force broke contact and attempted to make good their escape across the Kumusi River.[11] In the confusion, the 144th Infantry Regiment did not receive the order, and had to fight its way out at great cost, while the commander of the 41st Infantry Regiment, Yazawa, decided to cross the flood-swollen Oivi Creek and make for the coast, instead of establishing a rearguard.[13] This was followed by a resumption of the Australian pursuit as the Japanese continued to fall back towards the north. The Australians reached the Kumusi River, around Wairopi on 13 November,[23] where the Japanese were forced to abandon much of their artillery and a large amount of ammunition and other stores,[13] effectively drawing the Kokoda Track campaign to a close.[10]

Aftermath

The fighting around Oivi and Gorari was the last major battle of the Kokoda Track campaign, although it did not end the fighting in the area.[24][25] The wire bridge at Wairopi had been destroyed in an earlier Allied bombing raid, and so over the period 13 to 15 November, Australian engineers worked to establish crossing points, constructing several makeshift means including flying foxes and a narrow footbridge, enabling a small bridgehead to be established with one company at first. Due to limited engineering stores, the crossing proved slow and it was not until 15 November that the 25th Brigade had completed its crossing, allowing the 16th to follow them up. Meanwhile, patrols had been undertaken searching for isolated pockets of Japanese on the western side of the river, while reinforcements in the shape of the ad hoc Chaforce, consisting of one company from each battalion of the 21st Brigade, began arriving to reinforce the 25th Brigade. Late on 16 November, the Australians had completed their crossing, and the pursuit of the withdrawing Japanese forces continued.[26] The surviving Japanese from the Kokoda campaign subsequently gathered at the mouth of the Kumusi, joining up with Japanese reinforcements that were landed there in early December.[27] The months that followed saw heavy fighting on the northern coast of Papua, around Buna and Gona, as the Allies undertook a costly frontal assault against the Japanese beachheads, which had been heavily fortified.[28]

Australian casualties during the fighting around Oivi and Gorari amounted to 121 killed and 225 wounded.[13] In addition, there were also a large number of soldiers who became non-battle casualties due to disease.[29] Against this, the Japanese lost around 430 killed and around 400 wounded, and a large amount of war materiel, including 15 artillery pieces.[13] Additionally, the resultant need to cross the river – which was up to 100 metres (330 ft) wide in some places – as the Japanese withdrew further had the added effect of causing more losses due to drowning, with Horii himself becoming a victim of this fate as he attempted to raft and then canoe towards Giruawa.[30][31] In analysing the battle, author Peter Brune later wrote that Horii had erred in choosing to mount a stand around Gorari, with the ground beyond the Kumusi seemingly offering better defensive characteristics.[32] Nevertheless, Eustace Keogh writes that the Japanese defence had been conducted with "skill and determination" which had "made the Australians fight hard for their success".[23] Additionally, Craig Collie and Hajime Marutani note that the Japanese retreat succeeded in slowing the Australian advance long enough to allow Japanese engineers to establish a strong defensive system around Buna, Gona, and Sanananda.[33]

After the war, a battle honour was awarded to Australian units for their involvement in the fighting around Oivi and Gorari. This was designated "Oivi – Gorari".[34] This battle honour was awarded to the 3rd, 2/1st, 2/2nd, 2/3rd, 2/25th, 2/31st, 2/33rd Infantry Battalions.[35]

References

- Citations

- Keogh 1965, p. 168.

- James 2013, pp. 211–212.

- Williams 2012, p. 185.

- Anderson 2014, p. 121.

- Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 222–223.

- Keogh 1965, p. 215.

- Brune 2004, p. 403.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 236–237.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 307.

- "Kokoda: Overview". Australia's War 1939–1945. Department of Veterans' Affairs. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- Keogh 1965, p. 239.

- "Kokoda Recaptured". Our History. Australian Army. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "The Tide Turns: The Decisive Moment: Oivi–Gorari: 10 November 1942". The Kokoda Track: Exploring the Site of the Battle Fought by Australians in World War II. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 314.

- McCarthy 1959, pp. 313–314.

- Collie & Marutani 2009, pp. 175–176.

- Williams 2012, p. 212.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 321.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 313.

- McAulay 1992, p. 388.

- McCarthy 1959, pp. 322–323.

- McAulay 1992, p. 399.

- Keogh 1965, p. 240.

- McAulay 1992, p. 410.

- "The Battle of the Beachheads". Australia's War 1939–1945. Department of Veterans' Affairs. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- McCarthy 1959, pp. 329–333.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 444.

- "The Battle of Gorari". Military events. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- McCarthy 1959, p. 335.

- McAulay 1992, p. 404.

- Collie & Marutani 2009, pp. 188–191.

- Brune 2004, p. 419.

- Collie & Marutani 2009, p. 192.

- "Battle Honours of the Australian Army: World War Two: South West Pacific" (PDF). Australian Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Maitland 1999, p. 142.

- Bibliography

- Anderson, Nicholas (2014). To Kokoda. Australian Army Campaigns Series – 14. Sydney, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-922132-95-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brune, Peter (2004). A Bastard of a Place. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-403-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collie, Craig; Marutani, Hajime (2009). The Path of Infinite Sorrow: The Japanese on the Kokoda Track. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-839-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles. Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Karl (2013). "On Australia's Doorstep: Kokoda and Milne Bay". In Dean, Peter (ed.). Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–215. ISBN 978-1-10703-227-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Publications. OCLC 7185705.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maitland, Gordon (1999). The Second World War and its Australian Army Battle Honours. East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0-86417-975-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McAulay, Lex (1992). Blood and Iron: The Battle for Kokoda 1942. Sydney, New South Wales: Arrow Books. ISBN 0-09182-628-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959). South-West Pacific Area – First Year. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Volume 5. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134247.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Peter (2012). The Kokoda Campaign 1942: Myth and Reality. Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10701-594-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Tanaka, Kengoro (1980). Operations of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces in the Papua New Guinea Theater During World War II. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Papua New Guinea Goodwill Society. OCLC 9206229.

.jpg)