Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge was a battle of the American Revolutionary War fought near Wilmington in present-day Pender County, North Carolina, on February 27, 1776. The victory of North Carolina Revolutionary forces over Southern Loyalists helped build political support for the revolution and increased recruitment of additional soldiers into their forces.

Loyalist recruitment efforts in the interior of North Carolina began in earnest with news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and Patriots in the province also began organizing Continental Army and militia units. When word arrived in January 1776 of a planned British Army expedition to the area, Josiah Martin, the royal governor, ordered the Loyalist militia to muster in anticipation of their arrival. Revolutionary militia and Continental units mobilized to prevent the junction, blockading several routes until the poorly armed Loyalists were forced to confront them at Moore's Creek Bridge, about 18 miles (29 km) north of Wilmington.

In a brief early-morning engagement, a charge across the bridge by sword-wielding Loyalist Scotsmen was met by a barrage of musket fire. One Loyalist leader was killed, another captured, and the whole force was scattered. In the following days, many Loyalists were arrested, putting a damper on further recruiting efforts. North Carolina was not militarily threatened again until 1780, and memories of the battle and its aftermath negated efforts by Charles Cornwallis to recruit Loyalists in the area in 1781.

Background

British recruiting

In early 1775, with political and military tensions rising in the Thirteen Colonies, North Carolina's royal governor, Josiah Martin, hoped to combine the recruiting of Scots settlers in the North Carolina interior with that of sympathetic former Regulators (a group originally opposed to corrupt colonial administration) and disaffected Loyalists in the coastal areas to build a large Loyalist force to counteract Patriot sympathies in the province.[4] His petition to London to recruit 1,000 men had been rejected, but he continued efforts to rally Loyalist support.[5]

At about the same time, Scotsman Allan Maclean successfully lobbied King George III for permission to recruit Loyalist Scots throughout North America. In April, he received royal permission to raise a regiment known as the Royal Highland Emigrants by recruiting retired Scottish soldiers living in North America.[6] One battalion was to be recruited in the northern provinces, including New York, Quebec and Nova Scotia, while a second battalion was to be raised in North Carolina and other southern provinces, where a large number of these soldiers had been given land. After receiving his commissions from General Thomas Gage in June, Maclean sent Donald MacLeod and Donald MacDonald, two veterans of the June 17 Battle of Bunker Hill, south to lead the recruitment drive there. These recruiters were also aware that Allan MacDonald, husband of the famous Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald was already actively recruiting in North Carolina.[7] Their arrival at New Bern was cause for suspicion by members of North Carolina's Committee of Safety, but they were not arrested.[8]

On January 3, 1776, Martin learned that an expedition of more than 2,000 troops under the command of General Henry Clinton was planned for the southern colonies and that their arrival was expected in mid-February.[9] He sent word to the recruiters that he expected them to deliver recruits to the coast by February 15, and dispatched Alexander Maclean to Cross Creek (present-day Fayetteville) to coordinate activities in that area. Mclean optimistically reported to Martin that he would raise and equip 5,000 Regulators and 1,000 Scots. Martin is reported to have said "This is the moment when this country may be delivered from anarchy", expecting a North Carolina Loyalist victory.[4][10]

In a meeting of Scots and Regulator leaders at Cross Creek on February 5, there was disagreement on how to proceed. The Scots wanted to wait until the British troops had actually arrived before mustering, while the Regulators wanted to move immediately. The views of the latter prevailed since they claimed to be able to raise 5,000 men, while the Scots expected to raise only 700 to 800.[4] When the forces mustered on February 15, there were about 3,500 men, but the number rapidly dwindled over the next few days. Many men had expected to be met and escorted by British troops and did not relish the possibility of having to fight their way to the coast. When they marched three days later, Brigadier General Donald MacDonald led between 1,400 and 1,600 men, predominantly Scots.[2][3] This number was further reduced over the coming days as more men deserted the column.[11]

Revolutionary reaction

With the reaction of the revolutionary war, word of the Cross Creek meeting reached members of the Revolutionary North Carolina Provincial Congress a few days after it happened. The colonies were broadly prosperous on the eve of the American Revolution. Pursuant to resolutions of the Second Continental Congress, the provincial congress had raised the 1st North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army in fall 1775, and given command to Colonel James Moore. Local committees of safety in Wilmington and New Bern also had active militia organizations, led by Alexander Lillington and Richard Caswell respectively. On February 15 the Patriot forces began to mobilize.[3]

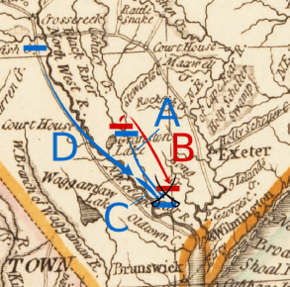

A: Moore moves from Wilmington to Rockfish Creek

B: MacDonald moves to Corbett's Ferry

C: Caswell moves from New Bern to Corbett's Ferry

Moore led 650 Continentals out of Wilmington with the objective of preventing the Loyalists from reaching the coast. They camped on the southern shore of Rockfish Creek on February 15, about 7 miles (11 km) from the Loyalist camp. General MacDonald learned of their arrival, and sent Moore a copy of a proclamation issued by Governor Martin and a letter calling on the rebels to lay down their arms. Moore responded with his own call that the Loyalists lay down their arms and support the cause of Congress.[3] In the meantime, Caswell led 800 New Bern District Brigade militiamen toward the area.[12] The Continentals included 58 Englishmen who had emigrated to North Carolina in the 1730s and 1740s and who were fighting for the Patriot cause, as well as 290 of their sons who had been born and raised in North Carolina. In addition to this were eleven Welshman and 39 of their American born sons who also fought under Lillington. Smaller numbers of Lowland Scots, primarily from the three Scottish counties of Selkirkshire, Berwickshire and Roxburghshire were also present on the Patriot side. Many of the men who fought under Lillington and Caswell were third generation Carolinians whose grandparents had been English immigrants who came as part of a large migration to the Carolinas from the English regions of Wiltshire, Northamptonshire, Hertfordshire as well as many farmers from the southern portion of Lincolnshire, England, during the early 1700s. By contrast, the Loyalist regiment facing them consisted exclusively of Scots Tories (specifically of Highland Scots background), who owned large plantations along the Cape Fear River which was settled by aristocrats from the region of the Scottish Highlands.[13]

Loyalist march

MacDonald, his preferred road blocked by Moore, chose an alternate route that would eventually bring his force to the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge, about 18 miles (29 km) from Wilmington. On February 20 he crossed the Cape Fear River at Cross Creek and destroyed the boats in order to deny Moore their use.[12] His forces then crossed the South River, heading for Corbett's Ferry, a crossing of the Black River. On orders from Moore, Caswell reached the ferry first, and set up a blockade there.[14] Moore, as a precaution against Caswell being defeated or circumvented, detached Lillington with 150 Wilmington militia and 100 men under Colonel John Ashe from the New Hanover Volunteer Company of Rangers to take up a position at the Widow Moore's Creek Bridge. These men, moving by forced marches, traveled down the southern bank of the Cape Fear River to Elizabethtown, where they crossed to the north bank. From there they marched down to the confluence of the Black River and Moore's Creek, and began entrenching on the east bank of the creek. Moore detached other militia companies to occupy Cross Creek, and followed Lillington and Ashe with the slower Continentals. They followed the same route, but did not arrive until after the battle.[12]

When MacDonald and his force reached Corbett's Ferry, they found the crossing blocked by Caswell and his men.[14] MacDonald prepared for battle, but was informed by a local slave that there was a second crossing a few miles up the Black River that they could use. On February 26, he ordered his rearguard to make a demonstration as if they were planning to cross while he led his main body up to this second crossing and headed for the bridge at Moore's Creek.[12] Caswell, once he realized that MacDonald had given him the slip, hurried his men the 10 miles (16 km) to Moore's Creek, and beat MacDonald there by only a few hours.[15] MacDonald sent one of his men into the Patriot camp under a flag of truce to demand their surrender, and to examine the defences. Caswell refused, and the envoy returned with a detailed plan of the Patriot fortifications.[16]

A: Caswell's movement

B: MacDonald's movement

C: Lillington and Ashe's movement

D: Moore's movement

Caswell had thrown up some entrenchments on the west side of the bridge, but these were not located to Patriot advantage. Their position required the Patriots to defend a position whose only line of retreat was across the narrow bridge, a distinct disadvantage that MacDonald recognized when he saw the plans.[15] In a council held that night, the Loyalists decided to attack, since the alternative of finding another crossing might give Moore time to reach the area. During the night, Caswell decided to abandon that position and instead take up a position on the far side of the creek. To further complicate the Loyalists' use of the bridge, the militia took up its planking and greased the support rails.[11]

Battle

By the time of their arrival at Moore's Creek, the Loyalist contingent had shrunk to between 700 and 800 men. About 600 of these were Highland Scots and the remainder were Regulators.[17] Furthermore, the marching had taken its toll on the elderly MacDonald; he fell ill and turned command over to Lieutenant Colonel Donald MacLeod. The Loyalists broke camp at 1 am on February 27 and marched the few miles from their camp to the bridge.[16] Arriving shortly before dawn, they found the defenses on the west side of the bridge unoccupied. MacLeod ordered his men to adopt a defensive line behind nearby trees when a Revolutionary sentry across the river fired his musket to warn Caswell of the Loyalist arrival. Hearing this, MacLeod immediately ordered the attack.[11]

In the pre-dawn mist, a company of Scots approached the bridge. In response to a call for identification shouted across the creek, Captain Alexander Mclean identified himself as a friend of the King, and responded with his own challenge in Gaelic. Hearing no answer, he ordered his company to open fire, beginning an exchange of gunfire with the Patriot sentries. Colonel MacLeod and Captain John Campbell then led a picked company of swordsmen on a charge across the bridge.[16]

During the night, Caswell and his men had established a semicircular earthworks around the bridge end, and armed them with two small pieces of field artillery. When the Scots were within 30 paces of the earthworks, the Patriots opened fire to devastating effect. MacLeod and Campbell both went down in a hail of gunfire; Colonel Moore reported that MacLeod had been struck by upwards of 20 musket balls. Armed only with swords and faced with overwhelming firepower from muskets and artillery, the Highland Scots could do little else other than retreat. The surviving elements of Campbell's company got back over the bridge, and the Loyalist force dissolved and retreated.[18]

Capitalising on the success, the Revolutionary forces quickly replaced the bridge planking and gave chase. One enterprising company led by one of Caswell's lieutenants forded the creek above the bridge, flanking the retreating Loyalists. Colonel Moore arrived on the scene a few hours after the battle. He stated in his report that 30 Loyalists were killed or wounded, "but as numbers of them must have fallen into the creek, besides more that were carried off, I suppose their loss may be estimated at fifty."[17] The Revolutionary leaders reported one killed and one wounded.[17]

Aftermath

Over the next several days, the Patriot forces mopped up the fleeing Loyalists. In all, about 850 men were captured. Most of these were released on parole, but the ringleaders were sent to Philadelphia as prisoners.[17] Combined with the capture of the Loyalist camp at Cross Creek, the Patriots confiscated 1,500 muskets, 300 rifles, and $15,000 (as valued at the time) of Spanish gold.[19] Many of the weapons were probably hunting equipment, and may have been taken from people not directly involved in the Loyalist uprising.[20] The action had a galvanizing effect on Patriot recruiting, and the arrests of many Loyalist leaders throughout North Carolina cemented Patriot control of the state. A pro-Patriot newspaper reported after the battle, "This, we think, will effectually put a stop to loyalists in North Carolina". Despite the hard feelings on both sides, the prisoners were treated with respect. This helped convince many not to take up arms against the Patriots again.[21]

The battle had significant effects within the Scots community of North Carolina, where Loyalists refused to turn out when calls to arms were made later in the war, and many were routed out of their homes by the pillaging activities of their Patriot neighbors.[19] Flora MacDonald ended up returning to her native Skye in 1779,[22] and when General Charles Cornwallis passed through the Cross Creek area in 1781, he reported that "[m]any of the inhabitants rode into camp, shook me by the hand, said they were glad to see us and that we had beat Greene and then rode home."[23]

When news of the battle reached London, it received mixed commentary. One news report minimised the defeat since it did not involve any regular army troops, while another noted that an "inferior" Patriot force had defeated the Loyalists.[19] Lord George Germain, the British official responsible for managing the war in London, remained convinced in spite of the resounding defeat that Loyalists were still a substantial force to be tapped.[21]

The expedition that the Loyalists had been planning to meet was significantly delayed, and did not depart Cork, Ireland until mid-February. The convoy was further delayed and split apart by bad weather, so the full force did not arrive off Cape Fear until May.[24] As the fleet gathered, North Carolina's provincial congress met at Halifax, and in early April passed the Halifax Resolves, authorizing the colony's delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence from Great Britain.[22] General Clinton used the force in an attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina. His attempt failed; it represented the end of significant British attempts to control the southern colonies until late 1778.[25]

The battlefield site was preserved in the late 19th century through private efforts that eventually received state financial support. The Federal government took over the battle site as a National Military Park operated by the War Department in 1926. The War Department operated the park until 1933, when the National Park Service began managing the site as the Moores Creek National Battlefield.[26] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[27] The battle is commemorated every year during the last full weekend of February.[28]

Troop numbers

Early accounts of the battle often misstated the size of both forces involved in the battle, typically reporting that 1,600 Loyalists faced 1,000 Patriots. These numbers are still used by the National Park Service.[29] Historian David Wilson, however, points out that the large Loyalist size is attributed to reports by General MacDonald and Colonel Caswell. MacDonald gave that figure to Caswell, and it represents a reasonable estimate of the number of men starting the march at Cross Creek. Alexander Mclean, who was present at both Cross Creek and the battle, reported that only 800 Loyalists were present at the battle, as did Governor Martin. The Patriot forces were also underreported since Caswell apparently casually grouped the ranger forces of John Ashe as part of Lillington's company in his report.[17]

Abandoning North Carolina Minutemen trial

The Patriot order of battle included a mix of North Carolina Minutemen and Militia units. Because of the performance of the local militia and the higher costs of Minutemen, the North Carolina General Assembly abandoned the use of Minutemen on April 10, 1776 in favor of local militia brigades and regiments. The following Patriot units participated in this battle:[30]

- New Bern District Minutemen Battalion, 13 companies

- Wilmington District Minutemen Battalion, 4 companies

- Halifax District Minutemen Battalion, 5 companies

- Hillsborough District Minutemen Battalion, 7 companies

- 1st Salisbury District Minutemen Battalion, 1 company

- 2nd Salisbury District Minutement Battalion, 11 companies

- 1st North Carolina Regiment, 7 companies

- Halifax District Brigade

- Halifax County Regiment, 1 company

- Northampton County Regiment, 1 company

- Hillsborough District Brigade

- Chatham County Regiment, 4 companies

- Granville County Regiment, 1 company

- Orange County Regiment, 1 company

- Wake County Regiment, 4 companies

- New Bern District Brigade

- Craven County Regiment, 4 companies

- Dobbs County Regiment, 8 companies

- Johnston County Regiment, 5 companies

- Pitt County Regiment, 4 companies

- Salisbury District Brigade

- Anson County Regiment, 2 companies

- Guilford County Regiment, 12 companies

- Surry County Regiment, 3 companies

- Tryon County Regiment, 8 companies

- Wilmington District Brigade

- Bladen County Regiment, 8 companies

- Brunswick County Regiment, 1 company

- Cumberland County Regiment, 2 companies

- Duplin County Regiment, 10 companies

- Onslow County Regiment, 3 companies

- New Hannover County Regiment, 2 companies of volunteer independent rangers

Notes

- Wilson, p. 34

- Wilson, p. 35

- Russell, p. 80

- Russell, p. 79

- Meyer, p. 140

- Fryer, p. 118

- Fryer, pp. 121–122

- Demond, p. 91

- Meyer, p. 142

- Wilson, p. 23

- Wilson, p. 28

- Russell, p. 81

- North Carolina in the American Revolution by Hugh F. Rankin pg. 101-103, 1959 - ISBN 9780865260917

- Wilson, p. 26

- Wilson, p. 27

- Russell, p. 82

- Wilson, p. 30

- Wilson, p. 29

- Russell, p. 83

- Wilson, p. 31

- Wilson, p. 33

- Russell, p. 84

- Demond, p. 137

- Russell, p. 85

- Wilson, p. 56

- Capps and Davis

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Moores Creek National Battlefield – Things to do". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- "Moores Creek National Battlefield website". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- Lewis

References

- Capps, Michael A.; Davis, Stephen A (1999). "Moores Creek National Battlefield – Administrative History". National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- Demond, Robert O (1979) [1940]. The Loyalists in North Carolina During the Revolution. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8063-0839-5. OCLC 229188174.

- Fryer, Mary Beacock (1987). Allan Maclean, Jacobite General: the Life of an Eighteenth Century Career Soldier. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-011-3. OCLC 16042453.

- Greene, Jack P. (February 2000). "The American Revolution". American Historical Review. 1. 105 (1): 91–102. doi:10.2307/2652437. JSTOR 2652437.

- Lewis, J.D. "Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge". The American Revolution in North Carolina. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Meyer, Duane (1987) [1961]. The Highland Scots of North Carolina, 1732–1776. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4199-0. OCLC 316095450.

- Murray, Aaron (2004). The American Revolution Battles and Leaders. New York: DK Publishing. pp. 30–31.

- Purcell, L. Edward & Sarah J. (2000). Encyclopedia of Battles in North America 1517 to 1916. New York: Facts on File Inc. p. 187.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0783-5. OCLC 44562323.

- Wilson, David K (2005). The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-573-3. OCLC 56951286.

External links

- State of North Carolina website for the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

- "The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge," Revolutionary North Carolina, a digital textbook produced by the UNC School of Education.