Battle of Lissa (1811)

The Battle of Lissa, also known as the Battle of Vis; French: Bataille de Lissa; Italian: Battaglia di Lissa; Croatian: Viška bitka) was a naval action fought between a British frigate squadron and a much larger squadron of French and Italian frigates and smaller vessels on Wednesday, 13 March on 1811 during the Adriatic campaign of the Napoleonic Wars. The engagement was fought in the Adriatic Sea for possession of the strategically important Croatian island of Vis (Lissa in Italian), from which the British squadron had been disrupting French shipping in the Adriatic. The French needed to control the Adriatic to supply a growing army in the Illyrian Provinces, and consequently dispatched an invasion force in March 1811 consisting of six frigates, numerous smaller craft and a battalion of Italian soldiers.

The French invasion force under Bernard Dubourdieu was met by Captain William Hoste and his four ships based on the island. In the subsequent battle, Hoste sank the French flagship, captured two others, and scattered the remainder of the Franco-Venetian squadron. The battle has been hailed as an important British victory, due to both the disparity between the forces and the signal raised by Hoste, a former subordinate of Horatio Nelson. Hoste had raised the message "Remember Nelson" as the French bore down, and had then manoeuvred to drive Dubourdieu's flagship ashore and scatter his squadron in what has been described as "one of the most brilliant naval achievements of the war".[3]

Background

The Napoleonic Wars, the name for a succession of connected conflicts between the armies of the French Emperor Napoleon and his European opponents, were nine years old when the War of the Fifth Coalition ended in 1809. The Treaty of Schönbrunn that followed the war gave Napoleon possession of the final part of Adriatic coastline not under his control: the Illyrian Provinces. This formalised the control the French had exercised in Illyria since 1805 and over the whole Adriatic Sea since the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807.[4] In the Treaty of Tilsit, Russia had granted France control over the Septinsular Republic and withdrawn their own forces from the region, allowing Napoleon freedom of action in the Adriatic.[5] At Schönbrunn, Napoleon made the Illyrian Provinces part of metropolitan France and therefore under direct French rule, unlike the neighbouring Kingdom of Italy which was nominally independent but in reality came under his personal rule.[6] Thus, the Treaty of Schönbrunn formalised Napoleon's control of almost the entire coastline of the Adriatic and, if unopposed, would allow him to transport troops and supplies to the Balkans. The French army forming in the Illyrian Provinces was possibly intended for an invasion of the Ottoman Empire in conjunction with the Russians;[6] the two countries had signed an agreement to support one another against the Ottomans at Tilsit.[4]

To disrupt the preparations of this army, the British Royal Navy, which had controlled most of the Mediterranean since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, seized the Dalmatian Island of Lissa in 1807 and used it as a base for raiding the coastal shipping of Italy and Illyria. These operations captured dozens of ships and caused panic and disruption to French strategy in the region.[7] To counter this, the French government started a major shipbuilding programme in the Italian seaports, particularly Venice, and despatched frigates of their own to protect their shipping. Commodore Bernard Dubourdieu's Franco-Venetian forces were unable to bring the smaller British force under William Hoste to a concerted action, where Dubourdieu's superior numbers might prove decisive. Instead, the British and French frigate squadrons engaged in a campaign of raids and counter-raids during 1810.[8]

In October 1810, Dubourdieu landed 700 Italian soldiers on Lissa while Hoste searched in vain for the French squadron in the Southern Adriatic.[9] The island had been left in the command of two midshipmen, James Lew and Robert Kingston, who withdrew the entire population of the island into the central mountains along with their supplies.[10] The Italian troops were left in possession of the deserted main town, Port St. George.[11] The French and Italians burnt several vessels in the harbour and captured others, but remained on the island for no more than seven hours, retreating before Hoste returned.[12] The remainder of the year was quiet, the British squadron gaining superiority after being reinforced by the third-rate ship of the line HMS Montagu.[13]

Early in 1811 the raiding campaigns began again, and British attacks along the Italian coast prompted Dubourdieu to mount a second invasion of Lissa. Taking advantage of the temporary absence of Montagu, Dubourdieu assembled six frigates and numerous smaller craft and embarked over 500 Italian soldiers under Colonel Alexander Gifflenga.[14] The squadron amassed by Dubourdieu not only outnumbered the British in terms of men and ships, it was also twice as heavy in weight of shot.[15] Dubourdieu planned to overwhelm Hoste's frigate squadron and then invade and capture the island, which would eradicate the British threat in the Adriatic for months to come.[16]

Battle

Dubourdieu (as commodore) led a squadron consisting of six frigates (four of 40 guns and two of 32 guns), a 16-gun brig, two schooners, one xebec, and two gunboats. Three of his ships were from the French Navy, and the others from the Navy of the Kingdom of Italy. In addition the squadron carried 500 Italian soldiers. In the absence of Montagu, Hoste's squadron consisted of three frigates (one of 38 guns and two of 32 guns) and one 22-gun post ship. The island of Lissa itself was defended by a small number of local troops under the command of two midshipmen.

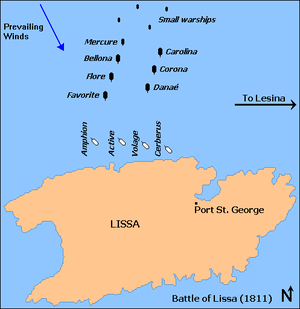

Dubourdieu's squadron was spotted approaching the island of Lissa at 03:00 on 12 March 1811 by Captain Gordon in HMS Active, which had led the British squadron from Port St George on a cruise off Ancona.[17] Turning west, the British squadron awaited the French approach in line ahead, sailing along the north coast of the island within half a mile of the shoreline. By 06:00, Dubourdieu was approaching the British line from the north-east in two divisions, leading in Favorite at the head of the windward or western division. Dubourdieu hoped to pass ahead of Active at the head of the British line and cross it further east with Danaé, which led the leeward division. Dubourdieu intended to break the British line in two places and destroy the British squadron in the crossfire.[18]

Over the next three hours the squadrons continued to close, light winds restricting them to a little over three knots.[2] A protege of Nelson, Hoste recalled the inspirational effect of Nelson's signal before the Battle of Trafalgar and raised his own: "Remember Nelson", which was greeted with wild cheering from the squadron.[16] As he closed with Hoste's force, Dubourdieu realised that he would be unable to successfully cross Active's bow due to the British ship's speed, and would also be unable to break through their line due to the British ships' close proximity to one another.[18] He instead sought to attack the second ship in the British line, Hoste's flagship HMS Amphion. Dubourdieu possessed not only a significant advantage in ships but also in men, the Italian soldiers aboard giving him the opportunity to overwhelm the British crews if he could board their frigates successfully.[16] The first shots of the battle were fired at 09:00, as the British used their wider field of fire to attack the leading French ships, Favorite and Danaé, unopposed for several minutes. The French squadron held their fire, Dubourdieu gathering his troops and sailors into Favorite's bow in order to maximise the effect of his initial attack once his flagship came into contact with Amphion.[2]

Hoste was aware of Dubourdieu's intentions and the French advantage in numbers, and consequently ordered a large 5.5-inch (140 mm) howitzer on Amphion's deck triple-shotted until the cannon contained over 750 musket balls[19] Once Favorite was within a few yards of Amphion's stern, Hoste gave permission for the gun to be fired and the cannon's discharge instantly swept the bow of Favorite clear of the French and Italian boarding party.[18] Among the dozens killed and wounded were Dubourdieu and all the frigate's officers, leaving Colonel Gifflenga in command of Favorite.[20] As Favorite and Amphion closed with one another, firing continued between the British rear and the French leeward division, led by Danaé. Several of the French ships came at an angle at which they could bring their guns to bear on HMS Cerberus, the rearmost British ship, and both sides were firing regular broadsides at one another.[2]

Hoste's manoeuvre

Following the death of Dubourdieu, Captain Péridier on Flore ordered the French and Venetian ships to attack the British line directly. The battered Favorite led with an attempt to round Amphion and rake her before catching her in crossfire, as had been Dubourdieu's original intention.[21] The remainder of the Franco-Venetian squadron followed this lead and attempted to bring their superior numbers to bear on the British squadron. Hoste was prepared for this eventuality and immediately ordered his ships to wear, turning south and then east to reverse direction. This movement threw the Franco-Venetian squadron into confusion and as a result the squadron's formation became disorganised.[20] Favorite, which had lost almost its entire complement of officers, was unable to respond quickly enough to the manoeuvre and drove onto the rocky coastline in confusion, becoming a total wreck.[22]

Thrown into further confusion by the loss of Favorite, the French and Venetian formation began to break up and the British squadron was able to pull ahead of their opponents; the leading French ships Flore and Bellona succeeded in only reaching Amphion, which was now at the rear of the British line.[18] Amphion found herself caught between the two frigates and this slowed the British line enough that the French eastern division, led by Danaé, was able to strike at HMS Volage, now the leading British ship after overtaking Cerberus during the turn.[23] Volage was much smaller than her opponent but was armed with 32-pounder carronades, short range guns that caused such damage to Danaé that the French ship was forced to haul off and reengage from a longer range. The strain of combat at this greater distance ruptured Volage's short-ranged carronades and left the ship much weakened, with only a single gun with which to engage the enemy.[24]

Chase

Engraved by Henri Merke after a painting by George Webster, 1812

Behind Volage and Danaé, the Venetian Corona had engaged Cerberus in a close range duel, during which Cerberus took heavy damage but inflicted similar injuries on the Italian ship. This exchange continued until the arrival of Active caused the Danaé, Corona and Carolina to sheer off and retreat to the east.[25] To the rear, Amphion succeeded in closing with and raking Flore, and caused such damage that within five minutes the French ship's officers threw the French colours overboard in surrender. Captain Péridier had been seriously wounded in the action, and took no part in Flore's later movements. Amphion then attacked Bellona and in an engagement that lasted until 12:00, forced the Italian ship's surrender.[26] During this combat, the small ship Principessa Augusta fired on Amphion from a distance, until the frigate was able to turn a gun on them and drive them off.[27] Hoste sent a punt to take possession of Bellona but due to the damage suffered was unable to launch a boat to seize Flore. Realising Amphion's difficulty, the officers of Flore, who had made hasty repairs during the conflict between Amphion and Bellona, immediately set sail for the French harbour on Lesina (Hvar), despite having already surrendered.[23][27]

Active, the only British ship still in fighting condition, took up pursuit of the retreating enemy and at 12:30 caught the Corona in the channel between Lissa and the small island of Spalmadon.[28] The frigates manoeuvred around one another for the next hour; captains Gordon and Pasqualigo each seeking the best position from which to engage. The frigates engaged in combat at 13.45, Active forcing Corona's surrender 45 minutes later after a fire broke out aboard the Italian ship.[29] Active too had suffered severely and as the British squadron was not strong enough to continue the action by attacking the remaining squadron in its protected harbour on Lesina, the battle came to an end.[10] The survivors of the Franco-Venetian squadron had all reached safety; Carolina and Danaé had used the conflict between Active and Corona to cover their escape while Flore had indicated to each British ship she passed that she had surrendered and was in British possession despite the absence of a British officer on board. Once Flore was clear of the British squadron she headed for safety, reaching the batteries of Lesina shortly after her Carolina and Danaé and ahead of the limping British pursuit. The smaller craft of the Franco-Venetian squadron scattered during the battle's final stages and reached Lesina independently.[10]

Conclusion

.jpg)

Engraving by Henri Merke after a painting by George Webster, 1812

Although Favorite was wrecked, over 200 of her crew and soldier-passengers had reached the land and, having set fire to their ship, prepared to march on Port St. George under the leadership of Colonel Gifflenga. Two British midshipmen left in command of the town organised the British and indigenous population into a defensive force and marched to meet Gifflenga. The junior British officers informed Gifflenga that the return of the British squadron would bring overwhelming numbers of sailors, marines and naval artillery to bear on his small force and that if he surrendered immediately he could expect better terms. Gifflenga recognised that his position was untenable and capitulated.[27][30] At Port St. George, the Venetian gunboat Lodola sneaked unnoticed into the harbour and almost captured a Sicilian privateer, Vincitore. The raider was driven off by the remaining garrison of the town without the prize, while attempting to manoeuvre her out of the bay.[31]

In the seas off Lissa, British prize crews were making strenuous efforts to protect their captures; Corona was heavily on fire in consequence of her engagement with Active and the British prize crew fought the blaze alongside their Italian prisoners. The fire was eventually brought under control, but not without the death of five men and several more seriously burnt when the blazing mainmast collapsed.[32] Problems were also experienced aboard Bellona, where Captain Duodo planned to ignite the powder magazine and destroy the ship following its surrender. Duodo had been mortally wounded in the action, and so ordered his second in command to light the fuse. The officer promised to do so, but instead handed control of the magazine to the British prize crew when they arrived. Duodo died still believing that the fuse had been lit.[32]

Hoste also remained at sea, cruising in the battered Amphion beyond the range of the shore batteries on Lesina. Hoste was furious at the behaviour of Flore's officers and sent a note into Lesina demanding that they give up the ship as indicated by its earlier surrender.[30] In surrendering and then escaping, the officers of Flore had breached an informal rule of naval conflict under which a ship that voluntarily struck its flag submitted to an opponent in order to prevent continued loss of life among its crew. Flore had been able to pass unmolested through the British squadron only because she was recognised to have surrendered, and to abuse this custom in this way was considered, in the Royal Navy especially, to be a dishonourable act.[10][30] The French at Lesina did not respond to Hoste's note, and the British squadron was eventually forced to return to Lissa to effect repairs.

Aftermath

Casualties of the action were heavy on both sides. The British ships suffered 190 killed or wounded in the battle and a number lost afterwards in the fire aboard Corona. Captains Hoste and Hornby were both badly wounded and the entire British squadron was in need of urgent repair before resuming the campaign.[33] In the French and Italian squadron the situation was even worse, although precise losses are not known. At least 150 had been killed aboard Favorite either in the action or the wreck, and the 200 survivors of her crew and passengers were all made prisoner. Bellona had suffered at least 70 casualties and Corona's losses were also severe.[33] Among the ships that escaped less is known of their casualties, but all required repair and reinforcement before the campaign could resume. Total French and Italian losses are estimated at no less than 700.[27] Losses among the officers of the combined squadron were especially high, with Commodore Dubourdieu and captains Meillerie and Duodo killed and Péridier seriously wounded.

The immediate aftermath saw renewed efforts by Hoste to induce the French to hand over Flore, efforts that were rebuffed by the captain of the Danaé, who had assumed command of the French squadron.[30] The surviving French and Venetian ships were initially laid up in Ragusa (Dubrovnik) awaiting supplies to continue the campaign, but a separate British squadron discovered and sank the supply ship at Parenzo (Poreč), necessitating a full French withdrawal from the area.[27] In Britain, Hoste's action was widely praised; the squadron's first lieutenants were all promoted to commander and the captains all presented with a commemorative medal.[22][34] Nearly four decades later the battle was also recognized in the issue of the clasp Lissa to the Naval General Service Medal, awarded to all British participants still living in 1847.[35] On their arrival in Britain, Corona and Bellone were repaired and later purchased for service in the Royal Navy, the newly built Corona being named HMS Daedalus and Bellone becoming the troopship Dover.[10] Daedalus was commissioned in 1812 under Captain Murray Maxwell, but served less than a year; wrecked off Ceylon in July 1813.[36]

British numerical superiority in the region was assured; when French reinforcements for the Adriatic departed Toulon on 25 March they were hunted down and driven back to France by Captain Robert Otway in HMS Ajax before they had even passed Corsica.[37] Throughout the remainder of 1811 however, British and French frigate squadrons continued to spar across the Adriatic, the most significant engagement being the action of 29 November 1811, in which a second French squadron was destroyed.[38] The action had significant long-term effects; the destruction of one of the best-trained and best-led squadrons in the French Navy and the death of the aggressive Dubourdieu ended the French ability to strike into the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire.[39]

Order of battle

| Captain Hoste's squadron | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||||

| HMS Active | Fifth rate | 38 | Captain James Alexander Gordon | 4 | 24 | 28[40] | ||||

| HMS Amphion | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain William Hoste | 15 | 47 | 62 | ||||

| HMS Volage | Sixth rate | 22 | Captain Phipps Hornby | 13 | 33 | 46 | ||||

| HMS Cerberus | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain Henry Whitby | 13 | 41 | 54 | ||||

| Casualties: 45 killed, 145 wounded, 190 total[40] | ||||||||||

| Commodore Dubourdieu's squadron | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Navy | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||||

| Windward division | ||||||||||

| Favorite | Fifth rate | 40 | Commodore Bernard Dubourdieu † Captain Antonie-Francois-Zavier La Marre-la-Meillerie † |

~150 | Driven ashore and destroyed. | |||||

| Flore | Fifth rate | 40 | Captain Jean-Alexandre Péridier | unknown | Surrendered but later escaped to safety. | |||||

| Bellona | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain Giuseppe Duodo † | ~70 | Captured and later commissioned into the Royal Navy as troopship HMS Dover. | |||||

| Leeward division | ||||||||||

| Danaé | Fifth rate | 40 | Captain Villon | unknown | ||||||

| Corona | Fifth rate | 40 | Captain Nicolò Pasqualigo | unknown | Captured and later commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Daedalus. | |||||

| |Carolina | Fifth rate | 32 | Captain Giovanni Palicuccia | unknown | ||||||

| Dubordieu's squadron was accompanied by the 16-gun brig Mercure, two small schooners Principessa Augusta and Principessa di Bologna, the xebec Eugenio and two gunboats (one named Lodola), none of which were heavily engaged. The squadron carried approximately 500 soldiers of the Italian Army under Colonel Alessandro Gifflenga. | ||||||||||

| Casualties: approximately 700 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||||||

| Sources: Gardiner, p. 173; Henderson, p. 112; James, p. 351; Smith, p. 356; Woodman, p. 253 | ||||||||||

Key

- A † symbol indicates that the officer was killed during the action or subsequently died of wounds received.

- The ships are ordered in the sequence in which they formed up for battle.

.svg.png)

Notes

- Paine p. 8

- James p. 352

- Hoste, Sir William, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, J. K. Laughton, Retrieved 22 May 2008

- Chandler p. 441

- Gardiner, p. 153

- Henderson, p. 111

- Gardiner, p. 154

- Henderson, p. 112

- Woodman, p. 253

- Henderson, p. 119

- James, p. 256

- Gardiner, p. 172

- Clowes, p. 472

- Sources differ on the spelling of Gifflenga's first name, using Alexander and Alexandre interchangeably.

- James, p. 360

- Henderson, p. 113

- Adkins, p. 358

- Gardiner, p. 173

- Adkins, p. 360

- Henderson, p. 115

- James p. 353

- Ireland p. 194

- Henderson, p. 116

- James p. 354

- James p. 355

- Woodman p. 255

- Gardiner, p. 174

- Henderson, p. 117

- Adkins, p. 361

- James, p. 361

- Woodman p. 256

- James, p. 358

- James, p. 357

- Henderson, p. 120

- "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. pp. 236–245.

- Grocott, p. 357

- James p. 362

- Gardiner, p. 178

- Adkins, p. 363

- This total does not include the five crew killed and several wounded extinguishing the fire aboard Corona in the aftermath of the action.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Lissa (1811). |

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-316-72837-3.

- Chandler, David (1999) [1993]. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Frasca, Francesco (2009) [2008]. Il potere marittimo in età moderna, da Lepanto a Trafalgar. Lulu Enterprises UK Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4092-6088-2.

- Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- Grocott, Terence (2002) [1997]. Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary & Napoleonic Era. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-164-5.

- Henderson, James (1994) [1970]. The Frigates, An Account of the Lighter Warships of the Napoleonic Wars. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-432-6.

- Ireland, Bernard (2000). Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-414522-4.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 5, 1808–1811. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-909-3.

- Paine, Lincoln P (2000). Warships of the World to 1900. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780547561707.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.