Barton S. Alexander

Barton Stone Alexander (September 4, 1819 – December 15, 1878) was a Union Army lieutenant colonel, engineer regiment commander and chief engineer for the defenses of Washington during the American Civil War. In recognition of his service, in 1866, he was appointed to the brevet rank of brigadier general in the regular army, to rank from March 13, 1865. He was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and served in the United States Army's Corps of Topographical Engineers, which at times was both a part of and separate from the United States Army Corps of Engineers. After graduating from West Point as a second lieutenant in the Class of 1842, he served in the Mexican–American War, building fortifications to protect American supply lines in the advance on Mexico City. After the end of the war, he was stationed in Washington, D.C., where he served as architect for the Scott Building and Quarters Buildings at the U.S. Soldiers' Home and took over the completion of the Smithsonian Institution Building after dissatisfaction with the pace of the first architect caused him to be dismissed.

Barton Stone Alexander | |

|---|---|

Brevet Brigadier General Barton S. Alexander, photograph date unknown | |

| Born | September 4, 1819 Nicholas County, Kentucky |

| Died | December 15, 1878 (aged 59) San Francisco, California |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Defenses of Washington, D.C. Pacific Military Engineering District |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War

|

After the completion of the Smithsonian in 1855, he traveled to New England, where he supervised the rebuilding of the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, a project widely considered to be one of the most difficult to be attempted by the U.S. Government up to that time.

During the American Civil War, he served as an advisor to the Engineering Brigade of the Army of the Potomac and became chief engineer of the defenses of Washington, D.C. Following the conclusion of hostilities, he served as chief engineer of the Military Division of the Pacific, making him the head engineer for every military construction project on the West Coast. In later years, he persuaded the U.S. government to acquire Pearl Harbor from the Kingdom of Hawaii and supervised numerous irrigation and land reclamation projects in California's central valley. He died on December 15, 1878, in San Francisco, California.

Pre-Civil War

Alexander was born in Nicholas County, Kentucky,[1] He entered West Point in the fall of 1838. Alexander was a diligent student, and corrected an entering weakness in mathematics to graduate seventh of 56 cadets in the Class of 1842. Between 1843 and 1848, he worked on several fortification projects along the East Coast of the United States, including Forts Pulaski, Jackson, and the defenses of New York City.[2] In 1848, he participated in the Mexican–American War as a second lieutenant of engineers, helping build defenses to protect American supply lines as Winfield Scott's army advanced on Mexico City. After the conclusion of the war, now-First Lieutenant Alexander returned to West Point for a four-year assignment as Treasurer and Superintending Engineer for the Cadets' Barracks and Mess Hall.[3] In 1852, Alexander was assigned to Washington, D.C., where he assisted in the design and construction of several government buildings.

The first of these was the Scott Building of the U.S. Soldiers' Home, now known as the Armed Forces Retirement Home. The building was named for General Winfield Scott, who donated $100,000 for the establishment of the Soldiers' Home in 1851. It served as the central focus of the complex, and still stands today.[4] Constructed in the Romanesque Revival style, the Scott Building features a round-arched motif utilizing white Vermont marble.[5]

At the same time as his work on the Scott Building, Alexander was asked to take up the challenge of completing the Smithsonian Institution Building, the progress of which had bogged down under architect James Renwick, Jr. In August 1853, Alexander accepted, and by 1855, the Smithsonian Building was complete.[3] During construction, Alexander slightly altered Renwick's original design by placing the Smithsonian's main lecture hall on the second floor. The change allowed for superior acoustics and a wider space than could be found on the first floor.[6] To support the large lecture hall and the central core of the building, Alexander arranged for the installation of fireproof masonry-encased iron structural columns. These would prove their value on January 24, 1865, when a fire broke out on the roof above the lecture hall. The resulting blaze destroyed the hall and damaged much of the rest of the structure. Thanks to the fireproof columns, however, the Smithsonian building did not collapse.[7]

Minot's Ledge Lighthouse

Following his work on the Smithsonian, but before the Scott Building finished construction, Alexander traveled to New England, where he was assigned to a project at the entrance of Boston harbor. That project, the rebuilding of Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, was widely considered to be one of the most difficult to be attempted by the U.S. Government up to that time.[8] Designed by Brigadier General Joseph Totten, head of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the lighthouse was intended to replace a structure that had been destroyed in an 1851 storm. With multiple ships wrecking on the ledge annually, the need for a lighthouse was crucial.[9] Appointed superintendent of the lighthouse construction in April 1855, newly promoted Captain Alexander modified Totten's design in accordance with conditions at the site. Because the site of the lighthouse was continually awash, except at low tide and calm seas, the work of preparing the interlocking granite blocks and iron framework of the lighthouse was done at nearby Government Island, adjacent to Cohasset, Massachusetts.[10]

The work progressed slowly, hampered by the partially submerged nature of the site, violent storms that wracked the area, and the fact that preparatory work had to be done away from the building site. During construction, a particularly violent storm hit the construction site, sweeping away much of the iron framework intended to support the stone shell of the lighthouse. Captain Alexander was discouraged, reportedly saying, "If wrought iron won't stand it, I have my fears about a stone tower."[11] Those fears were allayed when news reached Alexander that the damage had been due to a ship striking the lighthouse, rather than from just the storm alone. Work recommenced on building the lighthouse, and the final stone was laid on June 29, 1860, five years after Alexander and his workmen first landed at the ledge. The final cost of about $300,000 made it one of the most expensive lighthouses in United States history.[11]

Civil War

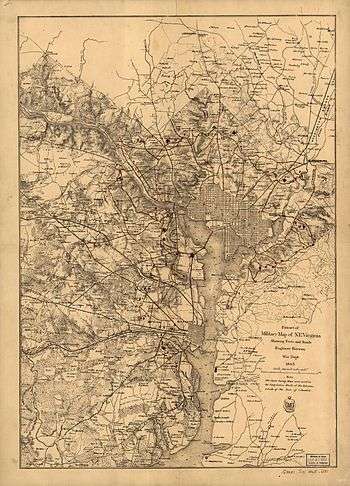

Following the completion of the Minot's Ledge Lighthouse project in 1860, the secession of South Carolina and the beginning of the American Civil War allowed Alexander to put his skills to military use for the first time since the Mexican-American War. On May 24, 1861, he was among several hundred engineers who marched into Virginia to begin building fortifications to protect Washington, D.C., which was located on the border between the Union state of Maryland and the Confederate state of Virginia.[12] In July 1861, the force that had marched into northern Virginia on May 24 found itself opposed by a large Confederate States Army force that had marched up from the south. In the haste to meet the Confederates in battle, Alexander found himself serving as an infantry officer and was assigned to the 1st Division of the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under the command of Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler.[13] It was a situation common to the young Union Army, which found itself short of experienced officers. Many engineer officers building defenses south of Washington were assigned to a regiment or division during the First Battle of Bull Run. Alexander received a brevet to major in the regular army for his service during the battle.[14]

Engineering Brigade

Following the defeat at Bull Run, the Union Army retreated back to the defenses of Washington. Throughout the remainder of 1861, the newly named Army of the Potomac, under the direction of its new commander, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, expanded and improved the improvised defenses that had been built in the seven weeks between the occupation of Northern Virginia and the Battle of Bull Run. New regiments arrived in Washington daily, and were placed in camps in and around the city. Two of these new arrivals—the 15th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment and the 50th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment—were designated "engineer regiments" and placed under the superintendence of Lt. Col. Alexander.[15] Following a brief training period under Alexander, the two regiments were declared to be an "Engineering Brigade" and placed under the command of Brig. Gen. Daniel P. Woodbury. Woodbury's brigade was itself under the command of Brig. Gen. John G. Barnard, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac. Alexander remained attached to the Engineering Brigade as an assistant.[16]

Alexander continued in this role during the Engineering Brigade's deployment with the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign, several times performing ably under hostile fire.[15] He was appointed a brevet lieutenant colonel for his service at the Siege of Yorktown, as of May 4, 1862.[14] Following the abandonment of the campaign and the return of the Army of the Potomac to northern Virginia, General Barnard, now chief engineer of defenses of Washington, D.C., requested Alexander serve as his aide-de-camp. Alexander accepted and served in that capacity throughout 1862.[17] When the Topographical Engineers and the Army Corps of Engineers were merged on March 3, 1863, Alexander (whose permanent U.S. Army rank was captain until this time) was promoted to major, while retaining his brevet (honorary) rank of lieutenant colonel.[18]

In August 1863, as part of his duties as aide-de-camp to General Barnard, Alexander was named as a member of a board of military officers who would examine the defenses of Washington and suggest improvements as needed. The board, created by the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, was designed to replace a civilian board that he had created in 1862.[19] In a November 1863 meeting, this board recommended final allotments of guns and ammunition for the forts protecting Washington, D.C., thus establishing the number of guns that would be in place during the Battle of Fort Stevens eight months later.[20]

Defenses of Washington, D.C.

On June 1, 1864, General Barnard was named the chief engineer of the Armies in the Field by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.[21] This move made Alexander the chief engineer for the defenses of Washington, filling the position vacated by Barnard's departure. It was a role he would take until well after the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865. The appointment was largely a caretaker role, as the final number of guns and forts had been established by the 1863 commission, and the Union Army's success in the field meant that no major force could threaten Washington. The only exception to this came in late July 1864, when Confederate forces under the command of Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early attacked Washington's defenses from the north during the Battle of Fort Stevens.

Following the conclusion of the war, Alexander presided over the drawdown in U.S. Army forces in Washington and the gradual decommissioning of the forts surrounding the city. On May 9, 1865, Alexander was ordered to stop work maintaining and improving the forts surrounding Washington as part of cost-cutting measures.[22] Alexander, not wishing to see Washington return to its defenseless pre-war state, recommended that some forts be continually maintained in order to preserve them for future needs.[23] The recommendations were accepted, but Alexander's ability to follow through on them was limited by an August order to "not incur expenses for hired labor" and the inability of the chief engineer of the District of Washington to furnish the large numbers of enlisted men needed to continue the upkeep.[24]

By January 1866, no funds were available even to keep Alexander's offices open, and on January 13, 1866, he declared, "... I closed up my office here, as far as it is possible to close it, before leaving ...".[25] By July 14, 1866, all of the outstanding debts of the office of the defenses of Washington were paid off in full and its work was fully completed.[26]

California years

On March 4, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Alexander for appointment to the grade of brevet brigadier general in the Regular Army, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the United States Senate confirmed the appointment on May 4, 1866.[27] Following his closure of the offices of the defenses of Washington, D.C., he was briefly ordered to New England, where he supervised the renovation of various minor fortifications and river improvements in Maine. That posting came to an end on January 7, 1867, when he was ordered to the West Coast as the chief U.S. Army engineer in the region.[28] He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on March 7, 1867.[14]

As chief engineer to the Military Division of the Pacific, he was the top U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officer on the entire American Pacific Coast.[29] Upon his arrival on the West Coast, he visited locations from Alaska to the Mexican border in order to analyze the work that would be needed. Between 1868 and 1870, he surveyed numerous California harbors and made engineering suggestions as required. One of these suggestions resulted in the construction of a 7,000-foot breakwater that made Long Beach harbor accessible to large amounts of shipping for the first time.[28] In 1870, he suggested that landowners near Colusa, California, construct levees to contain the Sacramento River within a single channel. The plan would reclaim swampland and control the river's annual floods, making large-scale farming possible. The plan was eagerly seized upon by local residents.[30]

In the spring of 1872, Col. Alexander and Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield, commander of the Military Division of the Pacific, sailed from San Francisco, California, to Honolulu in the then-independent Kingdom of Hawaii on a secret mission to evaluate Hawaii's ports in terms of defensive capabilities and commercial facilities. Fellow civil war veteran Alfred S. Hartwell was their host, who was on the kingdom's supreme court at the time.[31] They recognized the great potential of Pearl Harbor as a "harbor of refuge in time of war," and on May 8, 1873, recommended that the War Department acquire the harbor.[32] Their suggestion resulted in the signing of the reciprocity Treaty of 1875 between the United States and Hawaii. As part of the treaty, Hawaii ceded the area of Pearl Harbor to the United States in return for trade agreements benefiting Hawaiian sugar planters. The treaty was signed on September 8, 1876, helping pave the way for eventual American annexation of the Kingdom.[33]

Irrigation and land reclamation

Following his return to California, Col. Alexander was appointed president of a board appointed by the U.S. Congress to study the potential of irrigating the San Joaquin Valley, Tulare Valley, and Sacramento Valley.[34] The board, which became known as the Alexander Commission, conducted a survey of the California Central Valley throughout the summer and fall of 1873. The Commission's report declared that large-scale irrigation was possible and that much land could be reclaimed from the swamps around the Sacramento River. The report was not initially acted upon, but was the first professional survey of the valley and set the stage for further development.[29]

In 1874 and 1875, Alexander was assigned to a board examining the problem of keeping the Mississippi River Delta from silting up and becoming an impediment to ship traffic. During the course of his tenure on the board, he traveled to Europe in order to examine European solutions to the problem.[29] At the end of 1875, Alexander was asked by the state government of California to examine a proposed irrigation project in the San Joaquin Valley. Busy with other projects, Alexander appointed an associate, William Hammond Hall, to head the project.[29]

Alexander died in San Francisco, California, on December 15, 1878, at the age of 59.[35] He was buried in the San Francisco National Cemetery.[36]

References

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. "Barton Stone Alexander", Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- Introduction to Central Valley Irrigation projects, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, p. 19.

- Field, Cynthia R. "Director's Column: The Second Architect of the Smithsonian Building." Smithsonian Preservation Quarterly, Fall 1994 edition. The Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

- History of the Soldiers' Home and adjacent Lincoln Cottage Accessed September 5, 2007 Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Poppeliers, John C. and Chambers, S. Allen. What Style Is It?: A Guide to American Architecture. John Wiley and Sons, 2003. p. 56

- Upper Main Hall diagram, The Smithsonian. Archived 2009-04-20 at the Library of Congress Web Archives Accessed September 5, 2007

- Scott, Pamela. Capital Engineers: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Development of Washington, D.C., 1790–2004. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2007. Link Chapter 2, pp. 38–39.

- Kelley, Robert. Battling the Inland Sea: Floods, Public Policy, and the Sacramento Valley. University of California Press, 1998. p. 126.

- Boston Marine Society, Committee Report, November, 1838.

- History of Minot's Ledge Lighthouse, Cohasset Chamber of Commerce. Accessed September 5, 2007 Archived September 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Minot's Ledge Lighthouse History. Accessed September 5, 2007.

- U.S., War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington, D.C.: The Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, Volume 2, Chapter 9, p. 38.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 2, Chapter 9, p. 333.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3, p. 100.

- History of the Topographical Engineers, Engineers in the Civil War section. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 5, 2007.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 5, Chapter 14, p. 24.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 19, Chapter 31 Part 2 (serial 28), p. 420

- U.S. War Department, General Order No. 79, March 31, 1863. Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine September 5, 2007.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 29, Chapter 41 Part 2 (serial 49), p. 443.

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 29, Chapter 41 Part 2, pp. 394-95, 443

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 36, Chapter 48 Part 3 (serial 69), p. 600

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 46, Chapter 58 Part 3, (Serial 97), p. 1119

- Official Records, Series I, Volume 46, Chapter 58 Part 3, (Serial 97) p. 1130

- Engineer Orders and Circulars, Orders, Issuances, 1811 – 1941, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, Archives I, National Archives and Records Administration A2379, B.S. Alexander to Richard Delafield, December 5, 1865; Letters Received, 1826-66

- Engineer Orders, A2435, B.S. Alexander to Richard Delafield, January 13, 1866, Letters Received, 1826-66

- Engineer Orders, A2630, B.S. Alexander to Richard Delafield, July 14, 1866, Letters Received, 1826-66.

- Eicher, 2001, p, 731.

- Introduction, Corps of Engineers Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, p. 20.

- Kelley, p. 127

- Kelley, p. 128

- Alfred Stedman Hartwell (1946) [1908]. "Forty Years of Hawaii Nei". Fifty-fourth Annual Report. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 7–24. hdl:10524/51.

- Historical Background of PACAF Archived January 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, courtesy U.S. Defense Department. Accessed September 5, 2007.

- Pearl Harbor: Expansion Westward Accessed September 5, 2007.

- War Department, Adjutant-General's Office, Special Orders No. 73, April 9, 1873. Washington, D.C.

- Introduction, Army Corps of Engineers Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, p. 33.

- Findagrave.com, "Barton Stone Alexander".

External links

- Battery Alexander in California was named in Alexander's honor in 1901.