Barth syndrome

Barth syndrome (BTHS) is an X-linked[1] genetic disorder. The disorder, which affects multiple body systems, is diagnosed almost exclusively in males. It is named after Dutch pediatric neurologist Peter Barth.

| Barth Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria type II, |

| |

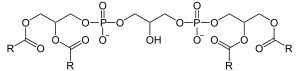

| Cardiolipin | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Presentation

Though not always present, the cardinal characteristics of this multi-system disorder include: cardiomyopathy (dilated or hypertrophic, possibly with left ventricular noncompaction and/or endocardial fibroelastosis),[2][3] neutropenia (chronic, cyclic, or intermittent),[3] underdeveloped skeletal musculature and muscle weakness,[4] growth delay,[3] exercise intolerance, cardiolipin abnormalities,[5][6] and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria.[3] It can be associated with stillbirth.[7]

Barth syndrome is manifested in a variety of ways at birth. A majority of BTHS patients are hypotonic at birth, show signs of cardiomyopathy within the first few months of life, and experience a deceleration in growth in the first year, despite adequate nutrition. As patients progress into childhood, their height and weight lag significantly behind other children. While most patients express normal intelligence, a high proportion of BTHS patients also express mild or moderate learning disabilities. Physical activity is also hindered due to diminished muscular development and muscular hypotonia. Many of these disorders are resolved after puberty. Growth accelerates during puberty, and many patients reach a normal adult height.[8]

Cardiomyopathy is one of the more severe manifestations of BTHS. The myocardium is dilated, reducing the systolic pump of the ventricles. For this reason, most BTHS patients have left myocardial thickening (hypertrophy). While cardiomyopathy can be life-threatening, it is commonly resolved or substantially improved in BTHS patients after puberty.[8] Neutropenia is another deadly manifestation of BTHS. Neutropenia is a granulocyte disorder that results in a low production of neutrophils, the body's primary defenders against bacterial infections. Surprisingly, however, BTHS patients have relatively fewer bacterial infections than other patients with neutropenia.[9]

Cause

Mutations in the tafazzin gene (TAZ, also called G4.5) are closely associated with Barth syndrome. The tafazzin gene product functions as an acyltransferase in complex lipid metabolism.[5][6] In 2008, Dr. Kulik found that all the BTHS individuals that he tested had abnormalities in their cardiolipin molecules, a lipid found inside the mitochondria of cells.[10] Cardiolipin is intimately connected with the electron transport chain proteins and the membrane structure of the mitochondria which is the energy producing organelle of the cell. The human tafazzin gene, NG_009634, is listed as over 10,000 base pairs in length and the full-length mRNA, NM_000116, is 1919 nucleotides long encoding 11 exons with a predicted protein length of 292 amino acids and a molecular weight of 33.5 kDa. The tafazzin gene is located at Xq28;[11] the long arm of the X chromosome. Mutations in tafazzin that cause Barth syndrome span many different categories: missense, nonsense, deletion, frameshift, splicing (see Human Tafazzin (TAZ) Gene Mutation & Variation Database).[12]

Diagnosis

Genetic blood test indicating deletion of the TAZ gene.

Treatment

Currently there is no treatment for Barth syndrome, although some of the symptoms can be successfully managed. There are currently clinical trials happening for possible treatments in the future like AAV9-mediated TAZ gene replacement strategy. The University of Florida has run a research investigation exploring the TAZ gene that has shown initial promising results, but more research and pre-clinical and clinical testing needs to be done before the gene therapy is approved by the FDA as a treatment.[14][15]

Epidemiology

It has been documented, to date, in more than 120 males (see Human Tafazzin (TAZ) Gene Mutation & Variation Database).[12] It is believed to be severely under-diagnosed[16] and may be estimated to occur in 1 out of approximately 300,000 births. Family members of the Barth Syndrome Foundation and its affiliates live in the US, Canada, the UK, Europe, Japan, South Africa, Kuwait, and Australia.

Barth syndrome has been predominately diagnosed in males, although by 2012 a female case had been reported.[17]

History

The syndrome was named for Dr. Peter Barth (pediatric neurologist) (1932-) in the Netherlands for his research and discovery in 1983.[4] He described a pedigree chart, showing that this is an inherited trait.

See also

- 3-Methylglutaconic aciduria

- noncompaction cardiomyopathy: mutations to the affected genes in Barth syndrome are also present here.

References

- Claypool SM, Boontheung P, McCaffery JM, Loo JA, Koehler CM (December 2008). "The cardiolipin transacylase, tafazzin, associates with two distinct respiratory components providing insight into Barth syndrome". Mol. Biol. Cell. 19 (12): 5143–55. doi:10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0896. PMC 2592642. PMID 18799610.

- Spencer CT, Bryant RM, Day J, et al. (August 2006). "Cardiac and clinical phenotype in Barth syndrome". Pediatrics. 118 (2): e337–46. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2667. PMID 16847078. S2CID 23163528.

- Kelley RI, Cheatham JP, Clark BJ, et al. (November 1991). "X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy with neutropenia, growth retardation, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria". The Journal of Pediatrics. 119 (5): 738–47. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80289-6. PMID 1719174.

- Barth PG, Scholte HR, Berden JA, et al. (December 1983). "An X-linked mitochondrial disease affecting cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and neutrophil leucocytes". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 62 (1–3): 327–55. doi:10.1016/0022-510X(83)90209-5. PMID 6142097. S2CID 22790290.

- Schlame M, Kelley RI, Feigenbaum A, et al. (December 2003). "Phospholipid abnormalities in children with Barth syndrome". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 42 (11): 1994–9. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.015. PMID 14662265.

- Vreken P, Valianpour F, Nijtmans LG, et al. (December 2000). "Defective remodeling of cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol in Barth syndrome". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 279 (2): 378–82. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2000.3952. PMID 11118295.

- Steward CG, Newbury-Ecob RA, Hastings R, et al. (October 2010). "Barth syndrome: an X-linked cause of fetal cardiomyopathy and stillbirth". Prenat. Diagn. 30 (10): 970–6. doi:10.1002/pd.2599. PMC 2995309. PMID 20812380.

- Kelley RI, [cited 6 Dec 2011]. “Barth Syndrome - X-linked Cardiomyopathy and Neutropenia”. Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Available from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-12-14. Retrieved 2004-12-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Barth Syndrome Foundation, 28 Jun 2011. “Diagnosis of Barth Syndrome”. Available from: "Barth Syndrome Foundation : Home". Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- Kulik W, van Lenthe H, Stet FS, et al. (February 2008). "Bloodspot assay using HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry for detection of Barth syndrome". Clinical Chemistry. 54 (2): 371–8. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2007.095711. PMID 18070816.

- Bione S, D'Adamo P, Maestrini E, Gedeon AK, Bolhuis PA, Toniolo D (April 1996). "A novel X-linked gene, G4.5. is responsible for Barth syndrome". Nature Genetics. 12 (4): 385–9. doi:10.1038/ng0496-385. PMID 8630491. S2CID 23539265.

- "Barth Syndrome Foundation : Home". Archived from the original on 2009-09-23. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Malhotra A, Edelman-Novemsky I, Xu Y, et al. (February 2009). "Role of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in the pathogenesis of Barth syndrome". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (7): 2337–41. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2337M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811224106. PMC 2650157. PMID 19164547.

- Suzuki-Hatano, Silveli; Saha, Madhurima; Rizzo, Skylar A.; Witko, Rachael L.; Gosiker, Bennett J.; Ramanathan, Manashwi; Soustek, Meghan S.; Jones, Michael D.; Kang, Peter B. (2018-08-02). "AAV-Mediated TAZ Gene Replacement Restores Mitochondrial and Cardioskeletal Function in Barth Syndrome". Human Gene Therapy. 30 (2): 139–154. doi:10.1089/hum.2018.020. ISSN 1043-0342. PMC 6383582. PMID 30070157.

- "Gene therapy for heart, skeletal muscle disorder shows promise in preclinical model | UF Health, University of Florida Health".

- Cantlay AM, Shokrollahi K, Allen JT, Lunt PW, Newbury-Ecob RA, Steward CG (September 1999). "Genetic analysis of the G4.5 gene in families with suspected Barth syndrome". The Journal of Pediatrics. 135 (3): 311–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70126-5. PMID 10484795.

- Cosson L, Toutain A, Simard G, Kulik W, Matyas G, Guichet A, Blasco H, Maakaroun-Vermesse Z, Vaillant MC, Le Caignec C, Chantepie A, Labarthe F (May 2012). "Barth syndrome in a female patient". Mol Genet Metab. 106 (1): 115–20. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.01.015. PMID 22410210.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |