Barnesville, Georgia

Barnesville is a city in Lamar County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 6,755,[5] up from 5,972 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Lamar County.[6]

Barnesville, Georgia | |

|---|---|

Barnesville City Hall | |

| Nickname(s): Buggy Town | |

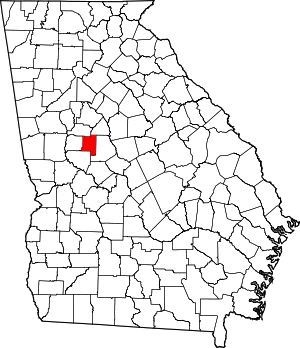

Location in Lamar County and the state of Georgia | |

| Coordinates: 33°3′11″N 84°9′22″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Lamar |

| Barnes' Store | 1826 |

| Barnesville | June 1831 |

| Incorporated City of Barnesville | February 20, 1854 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Council |

| • City Manager | Kenneth D. Roberts, Sr. |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.12 sq mi (15.86 km2) |

| • Land | 6.07 sq mi (15.73 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.12 km2) |

| Elevation | 850 ft (259 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,755 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 6,659 |

| • Density | 1,096.31/sq mi (423.28/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 30204 |

| Area code(s) | 770 |

| FIPS code | 13-05344[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0331094[4] |

| Website | www |

Barnesville was once dubbed the "Buggy Capital of the South", as the town produced about 9,000 buggies a year around the turn of the 20th century.[7] Each year in the third week of September the town hosts an annual Buggy Days celebration.

History

Barnesville was founded in 1826 and named for Gideon Barnes, proprietor of a local tavern.[8] In 1920, Barnesville was designated seat of the newly formed Lamar County.[9]

Barnesville served as a major hospital site for wounded southern troops during the Civil War. Local families took wounded soldiers into their homes and treated them, with highly successful recovery rates. Major General William B. Bate, CSA of Hardees Corps., wounded in Atlanta at Utoy Creek on August 10, 1864, was treated here. After the war, General Bate was elected governor of Tennessee and served in the United States Senate until his death in 1912. He commented on his successful recovery as a result of the kindness of the local populace in Barnesville.

Notable weather events

On the morning of April 28, 2011, at 12:38 A.M., a tornado rated EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale with 140 miles per hour (230 km/h) winds touched down in Pike County, 4 miles (6 km) south of Meansville. The tornado went on to destroy several homes in Barnesville. Two deaths occurred in Barnesville along Grove Street. The tornado also destroyed a Chevron gas station and a church in Barnesville. Three tractor trailers were blown off Interstate 75 at approximately 1:02 A.M. This tornado was part of the 2011 Super Outbreak.

Geography

Barnesville is located south of the center of Lamar County at 33°3′11″N 84°9′22″W (33.053090, -84.156217).[10] U.S. Route 41 passes through the western, southern, and eastern outskirts of the city on a bypass; the highway leads northwest 16 miles (26 km) to Griffin and east 13 miles (21 km) to Forsyth. U.S. Route 341 branches off US 41 on the south side of Barnesville and leads southeast 53 miles (85 km) to Perry, where it rejoins US 41. Georgia State Route 18 follows US 41 around the southern and eastern sides of Barnesville but leads west 11 miles (18 km) to Zebulon. State Route 36 follows the western side of the Barnesville bypass and leads northeast 22 miles (35 km) to Jackson and southwest 16 miles (26 km) to Thomaston.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Barnesville has a total area of 6.1 square miles (15.9 km2), of which 6.07 square miles (15.73 km2) are land and 0.05 square miles (0.12 km2), or 0.78%, are water.[11]

Barnesville sits on a low ridge at an elevation of 850 feet (260 m) above sea level. Hog Mountain rises above the city to the north, with a summit elevation of 1,015 feet (309 m). The north side of the city drains via Big Towaliga Creek to the Little Towaliga River, the Towaliga River, and eventually the Ocmulgee River. The east side drains via Tobesofkee Creek to the Ocmulgee south of Macon. The south end of the city drains via Tobler Creek to the Flint River, and the west side drains via Little Potato Creek, then Potato Creek, to the Flint River. Because the Ocmulgee River ultimately drains to the Atlantic Ocean and the Flint River ultimately to the Gulf of Mexico, Barnesville sits on the Eastern Continental Divide.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 754 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,962 | 160.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,839 | −6.3% | |

| 1900 | 3,036 | 65.1% | |

| 1910 | 3,068 | 1.1% | |

| 1920 | 3,059 | −0.3% | |

| 1930 | 3,236 | 5.8% | |

| 1940 | 3,535 | 9.2% | |

| 1950 | 4,185 | 18.4% | |

| 1960 | 4,919 | 17.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,935 | 0.3% | |

| 1980 | 4,887 | −1.0% | |

| 1990 | 4,747 | −2.9% | |

| 2000 | 5,972 | 25.8% | |

| 2010 | 6,755 | 13.1% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,659 | [2] | −1.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2011, there were 6,669 people, 2,079 households, and 1,382 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,055.9 people per square mile (407.4/km2). There were 2,257 housing units at an average density of 399.1 per square mile (154.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 48.11% White, 49.87% African American, 0.15% Native American, 0.33% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.57% from other races, and 0.94% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.69% of the population.

There were 2,079 households, out of which 31.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.1% were married couples living together, 25.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.5% were non-families. 29.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 23.6% under the age of 18, 17.7% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 18.5% from 45 to 64, and 13.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,375, and the median income for a family was $36,492. Males had a median income of $26,740 versus $20,160 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,423. About 16.1% of families and 20.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.5% of those under age 18 and 15.6% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Lamar County School District

The Lamar County School District holds pre-school to grade twelve, and consists of two elementary schools, a middle school, and a high school.[13] The district has 143 full-time teachers and over 2,600 students.[14]

- Lamar County Elementary School

- Lamar County Primary School

- Lamar County Middle School

- Lamar County Comprehensive High School

Private education

- St. George's Episcopal School (K-12)

- Rock Springs Christian Academy

- Covenant Heart Academy

Higher education

Annual events and festivals

The Barnesville-Lamar County Chamber of Commerce hosts three annual festivals each year.

- The BBQ & Blues Festival is held the last weekend in April and features an FBA(Florida Barbeque Association) certified cooking competition, food vendors, arts and crafts vendors, and live entertainment throughout the weekend.

- The Summer in the Sticks Country Music Concert is held the 3rd Saturday in July and features live bands, food vendors, and arts and crafts vendors. In 2014 it featured a guitar auction and cornhole tournament.

- The Buggy Days Festival celebrates Barnesville's heritage as the Buggy Capital of the South during the late 1800s. The event has been named a Top 20 Event in the Southeast for five out of eight years, often featured in major publications such as Southern Living magazine. Buggy Days is held on the third full weekend in September. More than 150 artists and craftspersons sell their handmade items on Main Street. Activities include a beauty pageant, concert, and vendors from throughout the region.

Nearby events include the following,

- The Vintage Karting Association with GSKA holds an annual 3-day kart race event in late March at Lamar County Speedway on Highway 36, just west of Barnesville's downtown. This well attended and noted weekend event attracts competitors from all over the United States and Canada who celebrate the glory days of kart racing competition in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Then, karters numbering in the hundreds invaded Barnesville, Forsyth, Griffin, and Thomaston for the Winter Olympics under International Kart Federation & World Karting Association sanction. GSKA currently leases the track and regularly holds races there.

Featured in media

Music

Barnesville was the location of an auto accident that killed 16-year-old Jeanette Clark, who was on a date with J.L. Hancock, also 16, on December 22, 1962. This accident was rumored to be the inspiration of the hit song "Last Kiss" written by Wayne Cochran, Joe Carpenter, Randall Hoyal & Bobby McGlon (1961). Hancock was driving a 1954 Chevrolet on the Saturday before Christmas with some friends. In heavy traffic on U.S. Highway 341 their car hit a tractor-trailer carrying a load of logs. Clark, Hancock and Wayne Cooper were killed. Cochran lived on Georgia's Route 19/41 when he wrote "Last Kiss", only 15 miles away from the crash site. He rerecorded "Last Kiss" for release on King Records in 1963 and dedicated it to Clark, a fact which probably explains the association of the song with the tragic crash.[16]

Television

The 2018 HBO miniseries Sharp Objects, starring Amy Adams, filmed many of its exterior scenes for the fictional town of Wind Gap, Missouri, in Barnesville and the surrounding area.[17] A large mural reading "Welcome to Wind Gap" remains in the town painted by artist Andrew Patrick Henry.[18]

Notable people

- Wayne Cochran - musician

- Franklin Delano Floyd - American murderer

- Louise Smith - NASCAR driver

- John T. Walker - Archbishop of Washington

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- American FactFinder - Results

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Buggy Capital of the South".

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- Hellmann, Paul T. (May 13, 2013). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 220. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Georgia". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Georgia Board of Education, Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- School Stats, Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- Gordon College, Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- "LAST KISS by J. FRANK WILSON & THE CAVALIERS". www.songfacts.com. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "How Sharp Objects Brought Wind Gap to Life". Vulture. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Barnesville, Georgia, Wind Gap Mural". Retrieved 23 May 2019.