Balkanization

Balkanization is a pejorative geopolitical term for the process of fragmentation or division of a larger region or state into smaller regions or states, which may be hostile or uncooperative with one another.[1][2]

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Primary topics |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

| Politics Portal |

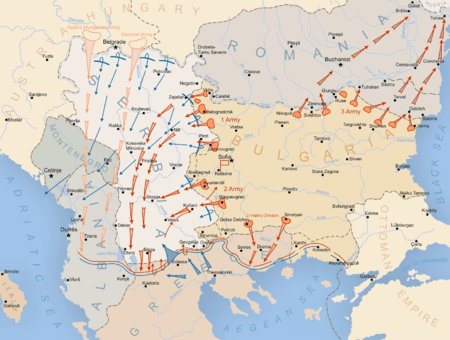

The term has its roots in the Spring of Nations and Balkan Wars, during which many independent Balkan states emerged from the protracted dissolution of the Ottoman Empire throughout the 19th and early 20th century.

Nations and societies

The term refers to the division of the Balkan peninsula, which was ruled almost entirely by the Ottoman Empire, into a number of smaller states between 1817 and 1912.[3] The term was coined in the early 19th century. Although it has a strong negative connotation,[4] it came into common use in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, with reference to the numerous new states that arose from the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire.

The larger countries within Europe, often the result of the union of several historical regions or nations, have faced the perceived issue of Balkanization. The Iberian Peninsula, especially Spain, has from the time of Al-Andalus had to come to terms with Balkanization,[5] with several separatist movements existing today, including Basque separatism and Catalan independentism.

Canada is a stable country but has separatist movements, the strongest of which is the Quebec sovereignty movement, which seeks to create a nation-state in Quebec, which encompasses the majority of Canada's French-Canadian population. Two referendums have been held to decide the question, one in 1980 and the last one in 1995. Both were lost by the separatists, the latter by a small margin. Less mainstream and smaller movements also exist in the Canadian Prairie, especially Alberta, to protest what is seen as a domination by Quebec and Ontario of Canadian politics. Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow also considered separation from Canada if the 1995 referendum had succeeded, which would have led to the balkanization of Canada.

Quebec has been the scene of a small but vociferous partition movement from the part of Anglo-Quebeckers activist groups opposed to the idea of independence of Quebec since 80% of the province is francophone. One such project is the Proposal for the Province of Montreal for the establishment of a separate province from Quebec for Montreal's strongly-anglophone and allophone (speaking neither English nor French) communities.

In January 2007, the growing support for Scottish independence made Chancellor of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom and later Prime Minister Gordon Brown talk of a "Balkanisation of Britain".[6] Independence movements in the United Kingdom also exist in England, Wales, Cornwall (itself part of England) and Northern Ireland.

In Africa

As Bates, Coatsworth & Williamson would argue, Balkanization was observed to a great extent in Africa. In the 1960s, countries in the Communauté financière africaine started to opt for "autonomy within the French community" in the postcolonial era.

Countries within the CFA franc zone were allowed to impose tariffs, regulate trade and manage transport services. Zambia, Malawi, Uganda and Tanzania achieved independence in the postcolonial era. The period also saw the breakdown of the Federation of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland as well as the East African High Commission. Balkanization was a result of the movement towards a closed economy. Countries were adopting antitrade and anti-market policies. Tariff rates were 15% higher than in OECD countries during the 1970s and 1980s.[7] Furthermore, countries took approaches to subsidise their own local industries, but the interior markets were small in scale. Transport networks were fragmented; regulations on labor and capital flow were more regulated; prices were under control. Between 1960 and 1990, balkanization led to disastrous results. The GDP of these regions were one tenth of OECD countries.[7] Balkanization also resulted in what van de Valle called "typically fairly overvalued exchanged rates" in Africa. Balkanization contributed to what Bates, Coatsworth & Williamson claimed to be a lost decade in Africa.

Economic stagnation ended only in the mid-1990s. Countries within the region started to input more stabilization policies. What was originally a high exchange rate eventually fell to a more reasonable exchange rate after devaluations in 1994. By 1994, the number of countries with an exchange rate 50 percent higher than the official exchange rate had decreased from 18 to four.[8] However, there is still limited progress in improving trade policies within the region, according to van de Walle. In addition, the post-independent countries still rely heavily on donors for development plans. Balkanization still has an impact on today's Africa. However, this causation narrative is not popular in many circles.

In Levant

Balkanization has been claimed to apply to Lebanon's political division between Muslims and Christians and to the Syrian Civil War as an attempt to create buffer states based on ethnic backgrounds in the Levant near Israel for its protection.[9][10]

See also

References

Footnotes

- "Balkanize". Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Vidanović 2006.

- Pringle 2016.

- Simic 2013, p. 128.

- McLean, Renwick (29 September 2005). "Catalonia steps up to challenge Spain". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "UK's Existence is at Risk – Brown". BBC News. 13 January 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Bates, Coatsworth & Williamson 2007.

- Van de Walle 2004.

- Georges Corm, La balkanisation du Proche-Orient, , Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 1983, pages 2 et 3.

- Guetta, Bernard (28 May 2013). "La balkanisation du Proche-Orient". Libération.fr (in French). Retrieved 28 September 2019.

Bibliography

- Bates, Robert H.; Coatsworth, John H.; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (2007). "Lost Decades: Postindependence Performance in Latin America and Africa" (PDF). The Journal of Economic History. 67 (4): 917–943. doi:10.1017/S0022050707000447. ISSN 1471-6372.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pringle, Robert W. (2016). "Balkanization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simic, Predrag (2013). "Balkans and Balkanisation: Western Perceptions of the Balkans in the Carnegie Commission's Reports on the Balkan Wars from 1914 to 1996". Perceptions. 18 (2): 113–134. ISSN 1300-8641.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van de Walle, Nicolas (2004). "Economic Reform: Patterns and Constraints". In Gyimah-Boadi, E. (ed.). Democratic Reform in Africa: The Quality of Progress. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 29–63. ISBN 978-1-58826-246-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vidanović, Ivan (2006). Rečnik socijalnog rada (in Serbian). Udruženje stručnih radnika socijalne zaštite Srbije; Društvo socijalnih radnika Srbije; Asocijacija centra za socijalni rad Srbije; Unija Studenata socijalnog rada. ISBN 978-86-904183-4-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links