Baháʼí Faith in Turkmenistan

The Baháʼí Faith in Turkmenistan begins before Russian advances into the region when the area was under the influence of Persia.[1] By 1887 a community of Baháʼí refugees from religious violence in Persia had made a religious center in Ashgabat.[1] Shortly afterwards — by 1894 — Russia made Turkmenistan part of the Russian Empire.[2] While the Baháʼí Faith spread across the Russian Empire[2][3] and attracted the attention of scholars and artists,[4] the Baháʼí community in Ashgabat built the first Baháʼí House of Worship, elected one of the first Baháʼí local administrative institutions and was a center of scholarship. During the Soviet period religious persecution made the Baháʼí community almost disappear — however, Baháʼís who moved into the regions in the 1950s did identify individuals still adhering to the religion. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, Baháʼí communities and their administrative bodies started to develop across the nations of the former Soviet Union;[5] In 1994 Turkmenistan elected its own National Spiritual Assembly[6] however, laws passed in 1995 in Turkmenistan required 500 adult religious adherents in each locality for registration and no Baháʼí community in Turkmenistan could meet this requirement.[7] As of 2007 the religion had still failed to reach the minimum number of adherents to register[8] and individuals have had their homes raided for Baháʼí literature.[9]

| Part of a series on |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

|

Central figures |

|

History |

|

Other topics |

History in the region

Community of Ashgabat

The Baháʼí community of Ashgabat (also spelled ʻIshqábád, Ashkhabad) was founded in about 1884, mostly from religious refugees from Persia.[10] One of the most prominent members of the community was Mirza Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpaygani, an Apostle of Baháʼu'lláh, who lived in Ashgabat off and on from 1889 to 1894. A short time after moving there, the assassination of one of the Baháʼís there, Haji Muhammad Rida Isfahani occurred and Gulpaygani helped the Baháʼí community to respond to this event and later he was the spokesman for the Baháʼís at the trial of the assassins. This event established the independence of the Baháʼí Faith from Islam both for the Russian government and for the people of Ashgabat.[11] Under the protection and freedom given by the Russian authorities, the number of Baháʼís in the community rose to 4,000 (1,000 children) by 1918 and for the first time anywhere in the world a true Baháʼí community was established, with its own hospitals, schools, workshops, newspapers,[12][13] cemetery, and House of Worship.[11] The city population was between 44 and 50 thousand at this time.[10]

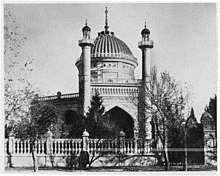

This first Baháʼí House of Worship was constructed inside the city of Ashgabat. The design of the building was started in 1902, and the construction was completed in 1908; it was supervised by Vakílu'd-Dawlih,[14] another Apostle of Baháʼu'lláh. The House of Worship in Ashgabat has been the only Baháʼí House of Worship thus far to have the humanitarian subsidiaries associated with the institution built alongside it.[15]

Community of Merv

The city of Merv (also spelled Marv, Mary) had a Baháʼí community, while it was far smaller and less developed. The Baháʼí community in the city received permission to build a House of Worship which they did on a smaller scale.[1][13]

Soviet period

By the time the effects of the October Revolution began to spread across the Russian Empire transforming it into the Soviet Union, Baháʼís had spread[14] east through Central Asia and Caucasus, and also north into Moscow, Leningrad, Tbilisi[16] and Kazan with the community of Ashgabat alone numbering about 3000 adults. After the October Revolution the Ashgabat Baháʼí community was progressively severed from the rest of the worldwide Baháʼí community.[14] In 1924 Baháʼís in Merv had schools and a special committee for the advancement of women.[17] Initially the religion still grew in organization when the election of the regional National Assembly of the Baháʼís of the Caucasus and Turkistan in 1925.[18]

However, the Baháʼí House of Worship was expropriated by the Soviet authorities in 1928, the Baháʼí schools had been closed in 1930,[13] and the House of Worship was leased back to the Baháʼís until 1938 when it was fully secularized by the communist government and turned into an art gallery. The records of events shows an increasing hostility to the Baháʼís between 1928 and 1938.[19] From 1928 free rent was set for five years, and the Baháʼís were asked to make certain repairs, which they did. But in 1933, before the five-year rent agreement expired the government suddenly decided expensive renovations would be required. These unexpected requirements were accomplished, but in 1934 complaints about the condition of the building were again laid. Inquires from abroad silenced the complaints. In 1936 escalated demands were made beyond the resources of the local community. The Baháʼís of Turkistan and the Caucasus rallied and were able to sustain the construction requested. Then the government made moves to confiscate the main gardens of the property to provide for a playground of a school (the school itself being confiscated from the Baháʼís originally) which would wall off the grounds from the Baháʼís — leaving only an entrance to the temple through a side entrance rather than the main entrance facing the front of the property. Protests lead to the abandonment of this plan; then in 1938 all pretexts came to an end.[19]

The 1948 Ashgabat earthquake seriously damaged the building and rendered it unsafe; the heavy rains of the following years weakened the structure. It was demolished in 1963 and the site converted into a public park.[14] With the Soviet ban on religion, the Baháʼís, strictly adhering to their principle of obedience to legal government, abandoned its administration and its properties were nationalized.[20] By 1938, with the NKVD (Soviet secret police) and the policy of religious oppression most Baháʼís were sent to prisons and camps or abroad; Baháʼí communities in 38 cities ceased to exist. In the case of Ashgabat, Baháʼí sources indicate[19] on 5 February the members of the assembly, leaders of the community and some general members of the community to a total of 500 people were arrested, homes were searched and all records and literature were confiscated (claiming they were working for the advantage of foreigners), and sometimes forced to dig their own graves as part of the interrogation. It is believed one woman set fire to herself and died later in a hospital. The women and children were largely exiled to Iran. In 1953 Baháʼís started to move to the Soviet Republics in Asia, after the head of the religion at the time, Shoghi Effendi, initiated a plan called the Ten Year Crusade. The Baháʼís who moved to Turkmenistan found some individual Baháʼís living there though the religion remained unorganized.[2][21] During the 1978-9 civil war in Afghanistan some Baháʼís fled to Turkmenistan.[22]

The first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly in the Soviet Union was elected in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, when conditions permitted it in 1989; 61 Baháʼís were listed as eligible for election. The Local Spiritual Assembly was officially registered by the city council of Ashgabat on 31 January 1990. Through the rest of 1990 several Local Spiritual Assemblies formed across the Soviet Union including Moscow, Ulan-Ude, Kazan, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Leningrad, and Murmansk.[5] In September 1990, 26 Baha'is gathered together for the election of the first Local Spiritual Assembly of Merv.[1] By September 1991, there were some 800 known Baha'is and 23 Local Spiritual Assemblies across the dissolving Soviet Union,[2] while in Turkmenistan there were about 125 Baháʼís with two Local Assemblies and two groups (in Balakhanih and Bayranali). When the National Spiritual Assembly of the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1992, a regional National Spiritual Assembly for the whole of Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kirgizia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) was formed with its seat in Ashgabat. Most of these countries went on to form their own National Spiritual Assembly,[1] and their communities went on to flourish (see Baháʼí Faith in Kazakhstan.)

Banned community

Since its inception, the religion has had involvement in socio-economic development — beginning by giving greater freedom to women.[23] promulgating the promotion of female education as a priority concern,[24] That involvement was given practical expression by creating schools, agricultural coops, and clinics.[23] The religion entered a new phase of activity when a message of the Universal House of Justice dated 20 October 1983 was released.[25] Baháʼís were urged to seek out ways, compatible with the Baháʼí teachings, in which they could become involved in the social and economic development of the communities where they lived. World-wide in 1979 there were 129 officially recognized Baháʼí socio-economic development projects. By 1987, the number of officially recognized development projects had increased to 1482. As the environment of Perestroika took hold across the Soviet Block, the Baháʼí community of Ashgabat was the first to re-form its Local Spiritual Assembly following the oppressive decades of Soviet rule, had doubled its numbers from 1989 to 1991, and had successfully registered with the city government of Ashgabat.

However, the nation of Turkmenistan revised its religious registration laws such that, in 1995, 500 adult religious adherent citizens were required in each locality for a religious community to be registered.[7] Thus by 1997 the Baháʼís were unregistered by the government along with several other religious communities.[26] More than just being unable to form administrative institutions, own properties like temples, and publish literature, perform scholarly work and community service projects — their membership in a religion is simply unrecognized: The religion is considered banned,[27] and homes are raided for Baháʼí literature.[9] As of 2007, under these harsh conditions, the Baháʼí community in Turkmenistan was unable to reach the required number of adult believers to be recognized by the government as a religion.[8] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 1000 Baháʼís across Turkmenistan in 2005.[28]

See also

References

- Momen, Moojan. "Turkmenistan". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 23 May 2008. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - Momen, Moojan. "Russia". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 14 April 2008. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv (2007–8). "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 2008-04-19. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Smith, Peter (2000). "Tolstoy, Leo". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 340. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. 1998 (8). pp. 35–44.

- Hassall, Graham; Universal House of Justice. "National Spiritual Assemblies statistics 1923-1999". Assorted Resource Tools. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- compiled by Wagner, Ralph D. "Turkmenistan". Synopsis of References to the Baháʼí Faith, in the US State Department's Reports on Human Rights 1991-2000. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- U.S. State Department (14 September 2007). "Turkmenistan - International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Corley, Felix (1 April 2004). "TURKMENISTAN: Religious communities theoretically permitted, but attacked in practice?". F18News.

- Momen, Moojan; ed. Shirin Akiner (1991). Cultural Change and Continuity in Central Asia, Chapter - The Baháʼí Community of Ashkhabad; its social basis and importance in Baháʼí History. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 278–305. ISBN 0-7103-0351-3. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2008.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Momen, Moojan. "Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpaygani, Mirza". Scholar's Official Website of Articles. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-23. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (21 February 2007), "The Bahaʼis of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {2/3}", Caucaz.com, archived from the original on 24 May 2011

- "Shining example Cradle of Faith". Baháʼí News. No. 675. June 1987. pp. 8–11. ISSN 0195-9212.

- Rafati, V.; Sahba, F. (1989). "Bahai temples". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- "Baha'i House of Worship - Ashkabad, Central Asia". The National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Azerbaijan. "Baha'i Faith History in Azerbaijan". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- "Foreign Baháʼí News". Baháʼí News. No. 6. July–August 1925. p. 7.

- Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". The Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 05 (3). Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- "Survey of Current Baha'i Activities in the East and West: Persecution and Deportation of the Baha'is of Caucasus and Turkistan". The Baha'i World. Wilmette: Baha'i Publishing Committee. VIII (1938–40): 87–90. 1942.

- Effendi, Shoghi (11 March 1936). The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh. Haifa, Palestine: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1991 first pocket-size edition. pp. 64–67.

- Effendi, Shoghi. Citadel of Faith. Haifa, Palestine: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1980 third printing. p. 107.

- National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Afghanistan (2008). "Baháʼí Faith in Afghanistan… A short History of Afghan Baháʼís". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Afghanistan. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Afghanistan. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- Momen, Moojan. "History of the Baha'i Faith in Iran". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 16 October 2009. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi (1997). "Education of women and socio-economic development". Baha'i Studies Review. 7 (1).

- Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19: 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.

- "TURKMENISTAN - Harassment and imprisonment of religious believers". Amnesty International. 1 March 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Corley, Felix (7 April 2004). "TURKMENISTAN: Religious freedom survey, April 2004". F18News.

- "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

Further reading

- ʻAlízád, Asadu'lláh (1999). trans. M'ani, Baharieh Rouhani (ed.). Years of Silence: Baháʼís in the USSR 1938–1946;The Memoirs of Asadu'llah ʻAlízád. Baha'i Heritage. George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-435-2.

- Soli Shahvar; Boris Morozov; Gad Gilbar (30 November 2011). Bahaʼis of Iran, Transcaspia and the Caucasus, The Volume 1: Letters of Russian Officers and Officials. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85772-068-9.