Bagni di Lucca

Bagni di Lucca (formerly Bagno a Corsena)[3] is a comune of Tuscany, Italy, in the Province of Lucca with a population of about 6,100.

Bagni di Lucca | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Bagni di Lucca | |

Coat of arms | |

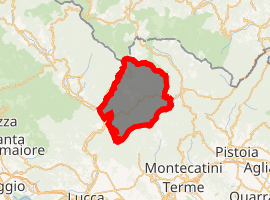

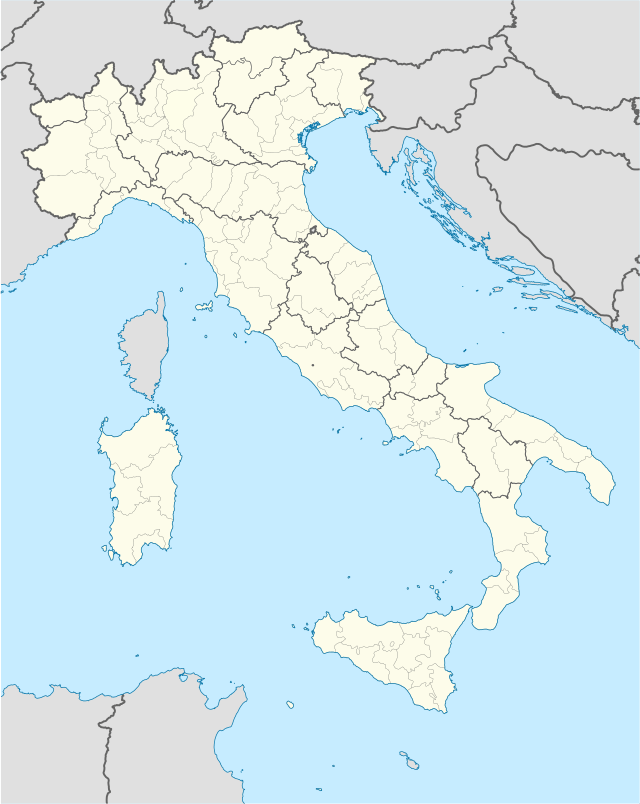

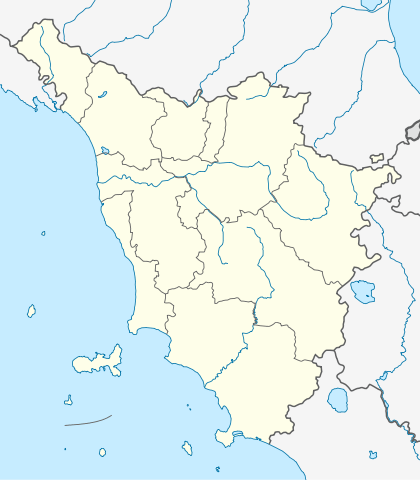

Location of Bagni di Lucca

| |

Bagni di Lucca Location of Bagni di Lucca in Italy  Bagni di Lucca Bagni di Lucca (Tuscany) | |

| Coordinates: 44°0′34″N 10°34′46″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Tuscany |

| Province | Lucca |

| Frazioni | Bagni Caldi, Benabbio, Brandeglio, Casabasciana, Casoli, Cocciglia, Crasciana, Fabbriche di Casabasciana, Fornoli, Granaiola, Isola, Limano, Lucchio, Lugliano, Montefegatesi, Monti di Villa, Palleggio, Pieve di Controni, Pieve di Monti di Villa, Ponte a Serraglio, San Cassiano di Controni, San Gemignano, Val Fegana, Vico Pancellorum |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Paolo Michelini |

| Area | |

| • Total | 164.65 km2 (63.57 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 150 m (490 ft) |

| Population (31 March 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 6,095 |

| • Density | 37/km2 (96/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Bagnaioli |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 55022 |

| Dialing code | 0583 |

| Patron saint | Saint Peter and Saint Paul |

| Saint day | 29 June |

| Website | Official website |

History

Bagni di Lucca has been known for its thermal springs since the Etruscan and Roman ages. The place was noted for the first time in an official document of 983 AD with the name of "Corsena", with reference to a donation by the Bishop Teudogrimo of the territory of Bagni di Lucca to Fraolmo of Corvaresi. The area is rich in chestnut forests, mentioned in the past by the Roman poet Virgil.

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, the village became a feudal property of the Suffredinghi, then the Porcareschi, and later the Lupari families. In the 12th century, the commune of Lucca occupied the territory of Bagni di Lucca. In 1308 Lucca unified the community of Bagni di Lucca with those of the nearby villages, forming a Vicarship named "Vicarship of the Lima Valley". Currently, each hamlet is governed by a member of the Bagni di Lucca parish. These members are responsible for the monitoring of religious festivals and preservation of old churches. Some of the earliest accounts of occupation were by the Lombards, whose leader was Alboin, who occupied the whole Serchio Valley for many years, building guard towers that were later converted to churches (e.g. Pieve di Controne).

During the 14th century, recognising the revenue from visitors to the thermal springs of Bagni di Lucca, Lucca restored the town. The commune developed it as a destination for visitors, including international figures.

Bagni di Lucca with its thermal baths reached its greatest fame during the 19th century, especially during the French occupation. The town became the summer residence of the court of Napoleon and his sister, Elisa Baciocchi. A casino was built, where gambling was part of social nightlife, as well as a large hall for dances.

At the Congress of Vienna (1814), the Duchy of Lucca was assigned to Maria-Louisa of Bourbon as ruler of Parma.[4] It continued as a popular summer resort, particularly for the English, who built a Protestant church there. The church now has been converted to the Bagni di Lucca Bibiloteca (library) and holds archives and records that date back to centuries ago.[5] In 1847 Lucca with Bagni di Lucca was ceded to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, under the domain of the Grand Duke Leopold II of Lorraine.[6] His rule started a period of decline for the springs and casino as a destination, since he was used to a secluded life. In 1853 the casino was closed. It was reopened after 1861, when Lucca became part of the unified Kingdom of Italy.[7]

World War II

During the German invasion of Italy in the 1940s, Bagni di Lucca was occupied along with many other towns along the Gothic Line in the Apennines. Several houses and mansions in the area were used as residences for German soldiers, and some residents born after 1940 in this region have German ancestry.

During the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state of Germany which existed from September 1943 until May 1945, a concentration camp for Jews was set up in Bagni di Lucca, where both Italian and foreign Jews were interned from December 1943 to January 1944. More than 100 people were interned in squalid conditions in the Hotel Le Terme. Some managed to escape, but most were sent to Auschwitz on 30 January 1944. Some Jews were moved between this camp and the Colle di Compecito (PG60) camp near Lucca.[8]

Main sights

In the valley of the Serchio, about 5 kilometres (3 mi) below Ponte a Serraglio, is the medieval Ponte della Maddalena (circa 1100), with a lofty central arch. It is also known as Ponte del Diavolo.[9] Il Ponte del Diavolo is known to have a few origins, however there is one main story. It is said that when a construction worker was working on the bridge late at night, the devil came up to him and offered assistance if he could claim the first passenger on the bridge. The agreement was made and when the bridge was finally built, a little dog wandered over the bridge and mysteriously disappeared. Many years later, another arch was added to the bridge for trains to pass by, this bridge is regarded as the most notable sight in the Bagni di Lucca area. Another bridge of interest is the Ponte delle Catene, Bagni di Lucca, a 19th-century suspension bridge. Also notable is the pieve (rural parish church) of San Cassiano, built by 722. It has the painting St. Martin Riding by Jacopo della Quercia and others from the Renaissance. There is also a war memorial in San Cassiano dedicated to the casualties of war (from World War I and World War II) from that town and its seven districts (Chiesa, Livizzano, Coccolaio, Capella, Cembroni, Vizzata, and Piazza). Every year a festival is held at the parish church and in the town of Controne to honor the 16th-century miracle that nobody in the town was infected with plague. A cross is carried and people march around the village rejoicing. Additional Renaissance works hang in the parish church of San Paolo a Vico Pancellorum (built 873).

The hospital in the frazione of Bagno Caldo was built in 1826 by the philanthropy of Nicholas Demidoff.[9] Additionally, temporary villas of previous poets, writers, etc. are also main sights. One of the main villas is that of the poets Robert Browning and his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who spent a lot of time in the town.

English Cemetery

The small English cemetery, recently restored, provides a final place of rest for the many foreign Protestant visitors who died in Bagni di Lucca. Some of the more notable graves, in order of the date of death, are of: Alexander Henry Haliday (1807-1870), Irish entomologist; Charles Isidore Hemans (1817-1876), English antiquary; Mahlon Dickerson Eyre (1821-1882), American art collector; English novelist Maria Louise Rame, better known as Ouida (1839-1908); Rose Cleveland (1846-1918), de facto First Lady of the United States; Nelly Erichsen (1862-1918), English illustrator and painter; Edward Perry Warren (1860-1928), English art collector; and Evangeline Marrs Whipple (1862-1930), American philanthropist and author.

Hot springs

The commune is known for its springs, in the valley of the Lima River, a tributary of the Serchio. The district is known in the early history of Lucca as the Vicaria di Val di Lima. Ponte Serraglio is the principal village of the warm spring area, but there are warm springs and baths also at Villa, Docce Bassi, and Bagno Caldo. The springs do not seem to have been known to the Romans. Bagno a Corsena is first mentioned in 1284 by Guidone de Corvaia, a Pisan historian (Muratori, R.I.S. vol. xxii.). Several writers and poets have since visited, including Dante on his way to Northern Italy.

Fallopius, who gave the springs credit for the cure of his own deafness, sounded their praises in 1569; and they have been more or less in fashion since. The temperature of the water varies from 36 to 54 °C (97 to 129 °F). In all cases, the springs give off carbonic acid gas and contain lime, magnesium and sodium products. The thermal springs were brought to much attention by natural medicinal doctor Montecatini of the University of Pisa in which "Montecatini Terme" is named after.[3]

Economy

The local economy is mainly based on tourism, attracted to the thermal springs, the historic architecture, and numerous quality hotels. Local industries produce paper and building materials, as well as machines. Many residents of the surrounding area produce their own and survive off local agriculture, however, there is a supermarket in the area, a few restaurants, cafes, and two weekend markets that bring foods and vegetable and fruits of all sorts to the public. Like many towns in Italy though, business has not been so great in Bagni di Lucca and local industries are moving to bigger areas and metropolises such as Milan. The population of the area is somewhat stable and the countryside is very quiet; tourism is and probably will be for a while the main source of income for Bagni di Lucca businessmen and workers.

Transportation

The main road that passes through Bagni di Lucca is SS12 which connected the Grand Duchy of Lucca to the Grand Duchy of Modena. There are several commuter buses that serve the commune of Lucca and Florence to the area. There is a train that goes through Bagni di Lucca and stops in the Fornoli section of town. Automobile is the best way to travel through Bagni di Lucca and to other hamlets on the outskirts of Bagni di Lucca town central.

Twin towns

Bagni di Lucca is twinned with:

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bagni di Lucca. |

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

-

- Starke M. Travels in Europe 9th Edition, John Murray, 1837, p48

- Starke (1837), pp 106-111

- Baedeker K. (1899) Northern Italy 11th Edition, Leipsic p395

- Baedeker (1899), p400

- Angelini, Silvia Q. (2018). "Bagni di Lucca". In Megargee, G.P.; White, J.R. (eds.). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume III: Camps and Ghettos under European Regimes Aligned with Nazi Germany. Indiana University Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-253-02386-5. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Chisholm 1911.