Aztlán

Aztlán (from Nahuatl languages: Aztlān, Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈast͡ɬaːn] (![]()

Legend

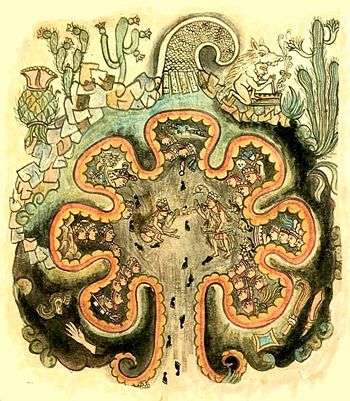

Nahuatl legends relate that seven tribes lived in Chicomoztoc, or "the place of the seven caves". Each cave represented a different Nahua group: the Xochimilca, Tlahuica, Acolhua, Tlaxcalteca, Tepaneca, Chalca, and Aztec. Because of their common linguistic origin, those groups are called collectively "Nahualteca" (Nahua people). These tribes subsequently left the caves and settled "near" Aztlán.

The various descriptions of Aztlán apparently contradict each other. While some legends describe Aztlán as a paradise, the Codex Aubin says that the Aztecs were subject to a tyrannical elite called the Azteca Chicomoztoca. Guided by their priest, the Aztec fled. On the road, their god Huitzilopochtli forbade them to call themselves Azteca, telling them that they should be known as Mexica. Scholars of the 19th century—in particular Alexander von Humboldt and William H. Prescott—translated the word Azteca, as is shown in the Aubin Codex to Aztec.[1][2]

Some say[3] that the southward migration began on May 24, 1064 CE, after the Crab Nebula events from May to July 1054. Each of the seven groups is credited with founding a different major city-state in Central Mexico.

A 2004 translation of the Anales de Tlatelolco gives the only date known related to the exit from Aztlan; day-sign "4 Cuauhtli" (Four Eagle) of the year "1 Tecpatl" (Knife) or 1064–1065,[3] and correlated to January 4, 1065.

Cristobal del Castillo mentions in his book "Fragmentos de la Obra General Sobre Historia de los Mexicanos", that the lake around the Aztlan island was called Metztliapan or "Lake of the moon." [4]

Places postulated as Aztlán

Friar Diego Durán (c. 1537–1588), who chronicled the history of the Aztecs, wrote of Aztec emperor Moctezuma I's attempt to recover the history of the Mexica by congregating warriors and wise men on an expedition to locate Aztlán. According to Durán, the expedition was successful in finding a place that offered characteristics unique to Aztlán. However, his accounts were written shortly after the conquest of Tenochtitlan and before an accurate mapping of the American continent was made; therefore, he was unable to provide a precise location.[6]

During the 1960s, Mexican intellectuals began to seriously speculate about the possibility that Mexcaltitán de Uribe was the mythical city of Aztlán. One of the first to consider Aztlán being linked to the Nayaritian island was historian Alfredo Chavero towards the end of the 19th century. Historical investigators after his death tested his proposition and considered it valid, among them Wigberto Jiménez Moreno. This hypothesis is still up for debate.[7]

Etymology

The meaning of the name Aztlan is uncertain. One suggested meaning is "place of Herons" or "place of egrets"—the explanation given in the Crónica Mexicáyotl—but this is not possible under Nahuatl morphology: "place of egrets" is Aztatlan.[8] Other proposed derivations include "place of whiteness"[8] and "at the place in the vicinity of tools", sharing the āz- element of words such as teponāztli, "drum" (from tepontli, "log").[8][9]

Use by the Chicano movement

.svg.png)

The concept of Aztlán as the place of origin of the pre-Columbian Mexican civilization has become a symbol for various Mexican nationalist and indigenous movements.

In 1969 the notion of Aztlan was introduced by the poet Alurista (Aberto Baltazar Urista Heredia) at the National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference held in Denver, Colorado by the Crusade for Justice. There he read a poem, which has come to be known as the preamble to El Plan de Aztlan or as "El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan" due to its poetic aesthetic. For some Chicanos, Aztlan refers to the Mexican territories annexed by the United States as a result of the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848. Aztlán became a symbol for mestizo activists who believe they have a legal and primordial right to the land. In order to exercise this right, some members of the Chicano movement propose that a new nation be created, a República del Norte.[10]

Aztlán is also the name of the Chicano studies journal published out of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Movements that use or formerly used the concept of Aztlán

- Brown Berets

- MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán, "Chicano Student Movement of Aztlán")

- Plan Espiritual de Aztlán

- Raza Unida Party

- Freedom Road Socialist Organization, which calls for self-determination for the Chicano nation in Aztlan up to and including the right to secession.[11]

In popular culture

In literature

- Aztlán has been used as the name of speculative fictional future states that emerge in the southwest U.S. or Mexico after the central U.S. government suffers collapse or major setback; examples appear in such works as the novels Heart of Aztlán (1976), by Rudolfo Anaya; Warday (1984), by Whitley Strieber and James Kunetka; The Peace War (1984), by Vernor Vinge; The House of the Scorpion (2002), by Nancy Farmer; and World War Z (2006), by Max Brooks; as well as the role-playing game Shadowrun, in which the Mexican government was usurped by the Aztechnology Corporation (1989). In Gary Jennings' novel Aztec (1980), the protagonist resides in Aztlán for a while, later facilitating contact between Aztlán and the Aztec Triple Alliance just before Hernán Cortés' arrival.

See also

References

- University, Sam Houston State. "Page Not Found: 404 – Sam Houston State University". SHSU Online. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- "Should We Call the Aztec Empire the Mexica Empire?".

- Anales de Tlatelolco, Rafael Tena INAH-CONACULTA 2004 p 55

- Fragmentos de la Obra General Sobre Historia de los Mexicanos, Cristobal del Castillo pages 58–83

- Rajagopalan, Angela Herren (2019). Portraying the Aztec Past: The Codices Boturini, Azcatitlan, and Aubin. University of Texas Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781477316078.

- Manuel Aguilar-Moreno Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. page 29.

- Hart, Tom. "Island of the Aztecs - Geographical". Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- Andrews (2003, p.496)

- Andrews (2003, p. 616)

- Professor Predicts 'Hispanic Homeland' Archived 2012-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press (reprinted by Aztlan.net), 2000

- Freedom Road Socialist Organization (FRSO). "Unity Statement". Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3452-6. OCLC 50090230.

- Clavigero, Francesco Saverio (1807) [1787]. The history of Mexico. Collected from Spanish and Mexican historians, from manuscripts, and ancient paintings of the Indians. Illustrated by charts, and other copper plates. To which are added, critical dissertations on the land, the animals, and inhabitants of Mexico, 2 vols. Translated from the original Italian, by Charles Cullen, Esq. (2nd ed.). London: J. Johnson. OCLC 54014738.

- Jáuregui, Jesús (2004). "Mexcaltitán-Aztlán: un nuevo mito". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Editorial Raíces. 12 (67): 56–61. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840. Archived from the original on 2006-01-03.

- Kunstler, James Howard (2005). The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-888-3. OCLC 57452547.

- Lint-Sagarena, Roberto (2001). "Aztlan". In Carrasco, David L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures :The Civilizations of Mexico and Central America vol.1. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-19-514255-6. OCLC 872326807.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (1988). The Great Temple of the Aztecs: Treasures of Tenochtitlan. New Aspects of Antiquity series. Doris Heyden (trans.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-39024-X. OCLC 17968786.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Prescott, William H. (1843). History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a Preliminary View of Ancient Mexican Civilization, and the Life of the Conqueror, Hernando Cortes (online reproduction, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library). New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 2458166.

- Pynchon, Thomas (2006). Against the Day. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-120-X. OCLC 71173932.

- Smith, Michael E. (1984). "The Aztlan Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?" (PDF online facsimile). Ethnohistory. Columbus, OH: American Society for Ethnohistory. 31 (3): 153–186. doi:10.2307/482619. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482619. OCLC 145142543.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7. OCLC 48579073.

- Vollemaere, Antoon Leon (2000). "Chimalma, first lady of the Aztecan migration in 1064" (PDF). Gender and Archaeology Across the Millennia: Long Vistas and Multiple Viewpoints. Sixth Gender and Archaeology Conference, October 6–7, 2000 (online collection of papers presented ed.). Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University, Department of Anthropology and Women's Studies. Archived from the original (PDF online publication) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- Wilcox, David R.; Don D. Fowler (Spring 2002). "The beginnings of anthropological archaeology in the North American Southwest: from Thomas Jefferson to the Pecos Conference" (unpaginated online reproduction by Gale/Cengage Learning). Journal of the Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, on behalf of The Southwest Center, U. of Arizona. 44 (2): 121–234. ISSN 0894-8410. OCLC 79456398.

External links

- Sanderson, Susana, "Tenotchtitlan and Templo Mayor", California State University, Chico.

- Aztlan Listserv (hosted by the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc.)

- League of Revolutionary Struggle, "The Struggle for Chicano Liberation" (an examination of Aztlan and the Chicano national movement from a Marxist point of view)

- Los Angeles artist protesting walls in Berlin, Palestine and Aztlán