Awaiting on You All

"Awaiting on You All" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released on his 1970 triple album, All Things Must Pass. Along with the single "My Sweet Lord", it is among the more overtly religious compositions on All Things Must Pass, and the recording typifies co-producer Phil Spector's influence on the album, due to his liberal use of reverberation and other Wall of Sound production techniques. Harrison recorded the track in London backed by musicians such as Eric Clapton, Bobby Whitlock, Klaus Voormann, Jim Gordon and Jim Price – many of whom he had toured with, as Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, in December 1969, while still officially a member of the Beatles. Musically, the composition reflects Harrison's embracing of the gospel music genre, following his production of fellow Apple Records artists Billy Preston and Doris Troy.

| "Awaiting on You All" | |

|---|---|

| Song by George Harrison | |

| from the album All Things Must Pass | |

| Published | Harrisongs |

| Released | 27 November 1970 |

| Genre | Rock, gospel |

| Length | 2:45 |

| Label | Apple |

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison |

| Producer(s) | George Harrison, Phil Spector |

| All Things Must Pass track listing | |

23 tracks

| |

In his lyrics to "Awaiting on You All", Harrison espouses a direct relationship with God over adherence to the tenets of organised religion. Influenced by both his association with London-based Hare Krishna devotees, known as the Radha Krishna Temple, and the Vedanta-inspired teachings of Swami Vivekananda, Harrison sings of chanting God's name as a means to cleanse and liberate oneself from the impurities of the material world. While acknowledging the validity of all faiths, in essence, his song words explicitly criticise the Pope and the perceived materialism of the Catholic Church – a verse that EMI and Capitol Records continue to omit from the album's lyrics. He also questions the validity of John Lennon and Yoko Ono's 1969 campaign for world peace, reflecting a divergence of philosophies between Harrison and his former bandmate after their shared interest in Hindu spirituality in 1967–68.

Several commentators have identified "Awaiting on You All" as one of the highlights of All Things Must Pass; author and critic Richard Williams likens it to the Spector-produced "River Deep – Mountain High", by Ike & Tina Turner.[1] The track is featured in the books 1001 Songs You Must Hear Before You Die by Robert Dimery and 1001 Songs by Toby Creswell. A similarly well-regarded live version, with backing from a large band including Clapton, Ringo Starr, Preston and Jim Keltner, was released on the 1971 album The Concert for Bangladesh and appeared in the 1972 film of the same name. Harrison's posthumous compilation Early Takes: Volume 1 (2012) includes a demo version of the song, recorded early in the 1970 sessions for All Things Must Pass.

Background

In his book While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Simon Leng describes George Harrison's musical projects outside the Beatles during 1969–70 – such as producing American gospel and soul artists Billy Preston and Doris Troy, and touring with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends – as the completion of "a musical-philosophical circle", which resulted in his post-Beatles solo album All Things Must Pass (1970).[2] Among the songs on that triple album, "My Sweet Lord" and "Awaiting on You All" each reflect Harrison's immersion in Krishna Consciousness,[3][4] via his association with the UK branch of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), known as the Radha Krishna Temple.[5] An ISKCON devotee since 1970, author Joshua Greene writes of All Things Must Pass providing an "intimately detailed account of a spiritual journey", which had begun with Harrison's embracing of Hinduism while in India in September–October 1966.[6]

Having long disavowed the Catholic faith of his upbringing,[7] from 1966 Harrison was inspired by the teachings of Indian yogi Swami Vivekananda.[8][9] The latter's contention that "Each soul is potentially divine, the goal is to manifest that divinity" particularly resonated with Harrison in its contrast to the doctrine of the Catholic Church.[10] By 1967, Harrison's religious awakening had progressed to include Gaudiya Vaishnava chanting,[11] a form of meditation that he shared with his Beatles bandmate John Lennon[12][13] and would go on to espouse in "Awaiting on You All".[14] Further to Vivekananda's assertion, chanting the Hare Krishna or other Sanskrit-worded mantras has, author Gary Tillery writes, "the ability to send spiritual energy through the body, leading to the enlightenment of the person chanting".[15]

Whereas Lennon's interest in spiritual matters waned following the Beatles' visit to India in 1968,[16][17][18] Harrison's involvement with the Radha Krishna Temple led to him producing two hit singles by the devotees over 1969–70, "Hare Krishna Mantra" and "Govinda".[19][20][nb 1] While Lennon and his partner, Yoko Ono, undertook a highly publicised campaign for world peace during 1969,[24][25] Harrison believed that all human suffering could be averted if individuals focused on addressing their own imperfections rather than, as he put it, "trying to fix everybody else up like the Lone Ranger".[26][27] This divergence in philosophy also formed part of Harrison's subject matter for "Awaiting on You All",[28] a song that, Greene writes, "projected his message to the world".[29]

Composition

– Harrison, on writing "Awaiting on You All"

In an October 1974 radio interview with Alan Freeman,[31] Harrison recalled writing "Awaiting on You All" while preparing to go to bed, and mentioned it as a composition that had come easily to him.[32] In his autobiography, I, Me, Mine, Harrison states that his inspiration for the song was "Japa Yoga meditation",[33] whereby mantras are sung and counted out on prayer beads.[34] Musically, the composition has elements of gospel and rock music;[35] Leng describes it as "gospel-drenched" and cites Harrison's production of "Sing One for the Lord", which Preston recorded with the Edwin Hawkins Singers in early 1970, as a "catalyst" for the new composition.[36] The song opens with a descending guitar riff,[37] later repeated after each chorus,[1] which ends on the melody's root chord of B major.[38]

In his lyrics to "Awaiting on You All", Harrison conveys the importance of experiencing spirituality directly, while rejecting organised religion as well as political and intellectual substitutes.[28] Author Ian Inglis writes that the lyrics recognise the merit in all faiths, as Harrison sings that the key to any religion is to "open up your heart".[39] The choruses proclaim that individual freedom from the physical or material world can be attained through "chanting the names of the Lord",[40] implying that there is a single deity who happens to be called by different names depending on the faith.[39][41]

The song's three verses[42] provide a list of items or concepts that are unnecessary to this realisation.[41][43] The opening lines – "You don't need no love-in / You don't need no bed pan" – serve as a criticism of Lennon and Ono's bed-ins and other forms of peace activism during 1969.[28][39] While Inglis views these words as indicative of a possible rift in Harrison's relationship with Lennon,[39] Leng identifies the "tongue-lashing for John and Yoko" as the singer dismissing "all political-cum-intellectual musings".[28][nb 2] Harrison then uses what Christian theologian Dale Allison terms "the language of pollution" to describe the problems afflicting the world,[46] and offers a method by which to cleanse oneself spiritually.[15]

In verse two,[47] Harrison sings of the futility of passports and travel for those searching to "see Jesus", since an open heart will reveal that Christ is "right there".[48] Allison remarks on the song expressing Harrison's "syncretistic view of Jesus", a view he shared with Lennon, and cites comments that Harrison later made to Radha Krishna Temple co-founder[49] Mukunda Goswami, that Christ was "an absolute yogi" yet modern-day Christian teachers misrepresent him and "[let] him down very badly".[50]

In the song's final verse,[51] Harrison states that churches, temples, religious texts and the rosary beads associated with Catholic worship are no substitute for a direct relationship with God.[41][43] These symbols of organised religion "meant searching in the wrong places", Tillery writes, when in keeping with Vivekananda's philosophy, "the spark of the divine is within us all. Every person is therefore the child of God ..."[52] AllMusic critic Lindsay Planer comments on Harrison's "observation of [religious] repression" in the lines "We've been kept down so long / Someone's thinking that we're all green."[43]

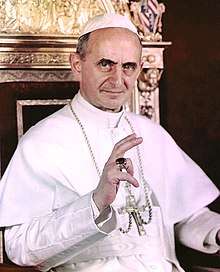

Harrison's most scathing criticism is directed at the Pope,[41] in the lines: "While the Pope owns 51% of General Motors / And the stock exchange is the only thing he's qualified to quote us."[28] Contrasting this statement with Harrison's song-wide message that God "waits on us to wake up and open our hearts", Allison concludes: "whereas the Lord is about the business of helping human beings to wake up, the Pope is about the business of business."[53]

In his book No Sympathy for the Devil, Dave Ware Stowe writes of the effect of "Awaiting on You All" on Evangelical Christian sensibilities: "this was dangerous stuff. Harrison's lyrics exemplified what many in the Jesus Movement considered a lure and snare of the devil. No doubt the song was spiritually resonant, even reverent, but it leaves the all-important object of veneration vague."[54]

While identifying a similar ISKCON-inspired theme in Harrison's 1973 song "The Lord Loves the One (That Loves the Lord)", Allison discusses "Awaiting on You All" as a precedent for further statements by Harrison against organised religion, particularly Catholicism.[53] Among these, Harrison parodied the Last Supper in his inner-gatefold artwork for Living in the Material World (1973),[55] dressed as a Catholic priest and again mocking the "perceived materialism and violence of the Roman church", according to Allison.[56][nb 3] In addition, in his role as film producer, Harrison supported Monty Python's controversial parodying of the biblical story of Christ in Life of Brian (1979),[60] about which he said: "Actually, [the film] was upholding Him and knocking all the idiotic stuff that goes on around religion."[61]

Production

Phil Spector's involvement

Harrison and American producer Phil Spector began discussing the possibility of Harrison recording a solo album of songs in early 1970,[62] after they had worked together on Lennon's Plastic Ono Band single "Instant Karma!"[63] Before then, to show his support for Spector's comeback from self-imposed retirement, Harrison had supplied a written endorsement of the producer's work on the Ike & Tina Turner album River Deep – Mountain High, when A&M Records issued the three-year-old recordings in 1969.[64][65][nb 4] Long a fan of Spector's sound,[68] Harrison praised River Deep – Mountain High with the words: "a perfect record from start to finish. You couldn't improve on it."[69]

Beatles biographer Peter Doggett suggests that Harrison had intended to make an entire album of devotional songs but, with that not being "an appropriate dish to set before Phil Spector", Harrison chose to delay starting work on All Things Must Pass and instead continued his activities with the Radha Krishna Temple.[70][nb 5] It was only after Paul McCartney's departure from the Beatles, and the band's break-up,[72] that Harrison finally began sessions for his solo album – in late May 1970, at Abbey Road Studios in London.[73] Noting Spector's application of his signature Wall of Sound production on "Awaiting on You All", Inglis writes that, but for Harrison's lyrics, the song "could be mistaken for the instrumental track of a song by the Ronettes",[74] one of Spector's girl-group protégés during the 1960s.[75]

Recording

The line-up of musicians on the basic track included Harrison and Eric Clapton, on electric guitars; bassists Klaus Voormann and Carl Radle, one of whom plays six-string bass;[76] and drummer Jim Gordon, who formed Derek and the Dominos with Clapton and Radle during the sessions.[77] In addition, Bobby Whitlock, the fourth member of the Dominos – all of whom were formerly part of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends[78] – recalls playing Hammond organ on the song.[79] Authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter note the presence of a piano part on the recording as well.[76]

In his 2010 autobiography, Whitlock writes of Lennon and Ono visiting the studio during the All Things Must Pass sessions, during which Lennon "got his socks blown off" by the music Harrison was recording.[80][nb 6] The Hare Krishna devotees regularly attended the sessions also;[82] Spector later cited their presence as an example of how Harrison inspired tolerance in non-believers, since the Temple devotees could be "the biggest pain in the necks in the world", according to Spector.[83][84] Among the many unreleased songs from the All Things Must Pass sessions, Harrison recorded his all-Sanskrit composition "Gopala Krishna",[85] which Leng describes as "a rocking companion to 'Awaiting on You All'".[86]

– Author Richard Williams, discussing "Awaiting on You All"

Madinger and Easter view "Awaiting on You All" as one of the more "heavily Spectorized" productions on All Things Must Pass,[76] due to Spector's liberal use of echo and other Wall of Sound techniques.[87] Among the extensive overdubs on the basic track, Harrison added what Leng terms a "virtual guitar orchestra" of harmonised slide guitar parts,[88] and former Delaney & Bonnie musicians[89] Jim Price and Bobby Keys supplied horns.[90] Whitlock and Clapton sang backing vocals with Harrison,[79] credited on the album as "the George O'Hara-Smith Singers".[91]

The recording also features prominent percussion such as tambourine and maracas.[1] While the precise line-up on many of the songs on All Things Must Pass continues to invite conjecture,[92][93] Badfinger drummer Mike Gibbins has said that Spector nicknamed him "Mr Tambourine Man" due to his role on that instrument throughout the sessions,[94] and that he and future Yes drummer Alan White played most of the percussion parts on the album, "switch[ing] on tambourine, sticks, bells, maracas ... whatever was needed".[95]

Release

Apple Records released All Things Must Pass on 27 November 1970,[96] with "Awaiting on You All" sequenced as the penultimate track on side three, in the original LP format, preceding the album's title song.[97] Of the 23 tracks released on All Things Must Pass, it was one of the few overtly religious songs.[98][nb 7] Concerned at the potential offensiveness of the lyrics, EMI omitted verse three of "Awaiting on You All" from the lyric sheet.[39] Madinger and Easter write that the lyrical content of this verse "probably shot down any chances of it being the hit single it could otherwise have been".[76]

Issued during a period when rock music was increasingly reflecting spiritual themes,[100] All Things Must Pass was a major commercial success,[101][102] outselling releases that year by Harrison's former bandmates,[103][104] and topping albums charts throughout the world.[105] Describing the impact of the album, with reference to "Awaiting on You All"'s exhortation to "chant the names of the Lord", author Nicholas Schaffner wrote of Harrison being "rewarded with a Number One single all over the world" with "My Sweet Lord".[106]

Reception

On release, Rolling Stone critic Ben Gerson described "Awaiting on You All" as "a Lesley Gore rave-up in which George manages to rhyme 'visas' with 'Jesus'".[107] While he considered that lyrics such as "You've been polluted so long" "carry an air of sanctimoniousness and moral superiority which is offensive", Gerson added: "Remarkably, he vindicates these lapses."[107] Writing for the same magazine 30 years later, Anthony DeCurtis opined that "the heart of All Things Must Pass resides in its songs of spiritual acceptance", and grouped "Awaiting on You All" with "My Sweet Lord" and "All Things Must Pass" as Harrison compositions that "capture the sweet satisfactions of faith".[108] In his 1970 review for the NME, Alan Smith described "Awaiting on You All" as "a rapid fire thumper with good chord progressions" and "one of the better tracks" on the album.[109][110] AllMusic critic Richie Unterberger views "Awaiting on You All" as a highlight of a collection on which "nearly every song is excellent",[111] while author and critic Bob Woffinden lists it with "My Sweet Lord", "Isn't It a Pity" and "What Is Life" as "all excellent songs".[112]

In his book Phil Spector: Out of His Head, Richard Williams writes that, unlike Lennon and McCartney on their 1970 solo albums, "Harrison concentrated on pure joyous melodies – the kind of songs that had made the group so loved", and he says of "Awaiting on You All": "Spector repaid Harrison for his benediction on the Ike and Tina Turner album cover by turning it into a virtual remake of 'River Deep – Mountain High'."[113] Mark Ribowsky, another Spector biographer, writes of the producer's contribution to this and other songs on All Things Must Pass: "Phil's rhythmically pounding basses and drum feels sutured George's sentimentality with cheerful energy and made Indian asceticism into dance music."[114] Simon Leng describes "Awaiting on You All" as a "hot gospel stomper" and "the most successful example of Spector's work on the album".[115] Writing for NME Originals in 2005, Adrian Thrills named "Awaiting on You All" and "Wah-Wah" as examples of "a tendency to over-egg the mix" on the otherwise "magnificent" All Things Must Pass, adding: "it is hard to think of another big rock album on which the tambourine is shaken quite so relentlessly."[116]

In his AllMusic article on the song, Lindsay Planer views it as "somewhat of a sacred rocker" with "ample lead guitar", and comments that Harrison's lyrics "cleverly [draw] upon an array of disparate imagery to convey a conversely simple spiritual revelation".[43] Harrison biographer Alan Clayson considers the track "more uplifting" than "My Sweet Lord" and remarks on the aptness of Harrison's subject matter in 1970–71, when religious texts such as the Bible, the Koran and ISKCON's Chant and Be Happy "now had discreet places on hip bookshelves".[117] Former Mojo editor Mat Snow describes the song as "glorious white gospel", in which Harrison "rejects the Catholicism of his Liverpool upbringing".[118]

"Awaiting on You All" has featured in the music reference books 1001 Songs You Must Hear Before You Die by Robert Dimery[119] and 1001 Songs by Australian critic Toby Creswell.[35] The latter describes the combination of Harrison's "tasteful" guitar parts and the "galloping" rhythm section as "sublime and divine".[35] In Dimery's book, contributor Bruno MacDonald writes of the track: "'Awaiting on You All' has a timeless exuberance that even Beatles-haters should experience."[120]

Live version

"Awaiting on You All" was one of the songs Harrison played at the Concert for Bangladesh,[121] held at Madison Square Garden, New York, on 1 August 1971.[122] Featuring backing from a band including Clapton, Voormann, Ringo Starr, Leon Russell, Billy Preston, Jim Keltner and Jim Horn,[123] Harrison performed the song at both the afternoon and the evening shows.[124] The latter performance was included on the Concert for Bangladesh live album, which Spector again co-produced,[125] and in the film of the concert.[126] Joshua Greene comments on there being a "logical chronology" to the first three songs in Harrison's setlist for this second show: "starting with 'Wah Wah,' which declared his independence from the Beatles; followed by 'My Sweet Lord,' which celebrated his internal discovery of God and spirit; and then 'Awaiting on You All'".[29]

Writing in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau compared the less-polished performance of "Awaiting on You All" with the studio version's "perfect production" and concluded: "it is exhilarating to hear his voice clearly singing the song for the first time, likewise the excellent guitar."[127] In his album review for Melody Maker, Williams wrote of Harrison's opening trio of songs: "Unbelievably, they're as good as the originals, and in some ways even better, because they combine the power of the arrangements for horns and rhythm with a sense of joy that comes only in live performance. The two drummers (Ringo and Jim Keltner) are just breathtaking on 'Awaiting' ..."[128] Planer also compliments what he calls "the tag-team percussion" of Starr and Keltner, which "driv[es] through the heart of the performance".[43]

Reissue and other versions

In February 2001, during his extensive promotion for the 30th anniversary reissue of All Things Must Pass,[129] Harrison named "Awaiting on You All" among his three favourite tracks on the album.[130][131] The electronic press kit accompanying the release included a scene where Harrison plays back the song at his Friar Park studio and isolates certain parts of the recording in turn, such as the backing vocals and slide guitars.[132] In the CD booklet, Harrison's liner notes conclude with a thank-you to "the amazing Mr. Phil Spector" and the acknowledgement: "He helped me so much to get this record made. In his company I came to realise the true value of the Hare Krishna Mantra."[133] The Pope-related lyrics in "Awaiting on You All" were again omitted from the booklet;[133] they similarly do not appear on the lyric sheet supplied with the 2014 Apple Years reissue.[134]

Part of the 2001 playback scene was included in Martin Scorsese's documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World,[135] and an early take from the 1970 sessions appeared on the bonus disc accompanying that film's DVD release in late 2011.[136] This demo version, which Harrison introduces as "Awaiting for You All",[137] was included on the compilation Early Takes: Volume 1 (2012).[138] Referring to Harrison's stated regret at the amount of echo Spector used on All Things Must Pass, compilation producer Giles Martin says of the song's sparse arrangement on Early Takes: "I think this is really cool, it's got a good basic band groove, I think of it as George breaking down a wall of sound."[137]

In 1971, Detroit band Silver Hawk released a cover version of "Awaiting on You All" as a single,[139] which peaked at number 108 on Billboard magazine's Bubbling Under listings.[140] In Canada, Silver Hawk's single climbed to number 49 on the RPM Top 100.[141] A cover "worth mentioning", according to Planer, is a version recorded by pedal steel guitarist Joe Goldmark, released on the 1997 tribute album Steelin' the Beatles.[43]

Personnel

According to authors Simon Leng and Bruce Spizer, the line-up of musicians on "Awaiting on You All" is as follows:[90][115]

- George Harrison – vocals, electric guitar, slide guitars, backing vocals

- Eric Clapton – electric guitar, backing vocals

- Bobby Whitlock – organ, backing vocals[79]

- Klaus Voormann – bass

- Carl Radle – bass

- Jim Gordon – drums

- Jim Price – trumpet, trombone, horn arrangement

- Bobby Keys – saxophones

- Mike Gibbins – tambourine

- uncredited – piano

- uncredited – maracas

Notes

- Among his non-musical activities on behalf of the Hare Krishna devotees, Harrison served as co-lessor for the Temple's new premises in central London,[21] and he financed the publication of ISKCON's 400-page KRSNA Book.[22][23]

- In an April 1970 radio interview in New York,[44] Harrison referred to his difference in ideology with Lennon: "This is really where I disagreed with John ... I don't think you get peace by going around shouting: 'GIVE PEACE A CHANCE, MAN!' ... [Instead,] put your own house in order; for a forest to be green, each tree must be green."[45]

- Among his later songs, Harrison sent up the Catholic faith in the posthumously released "P2 Vatican Blues".[57] In one of his final recordings before his death in November 2001, "Horse to the Water",[58] Harrison sings of a "truth seeker" being denied access to God, Leng writes, by "religious civil servants for whom the organization and the rules have become more important than the message".[59]

- Produced by Spector in 1966, the Turners' album was withdrawn from release following the disappointing commercial reception afforded its title song in America.[66] Considering "River Deep – Mountain High" his masterpiece, Spector temporarily withdrew from the music industry after the single's failure.[67]

- Harrison made a promotional visit to Paris with the ISKCON devotees in March 1970,[70] in addition to carrying out further recording in London for what became the Radha Krsna Temple album (1971).[71]

- In light of Harrison having had many of his songs turned down by Lennon and McCartney during the Beatles' career, Whitlock recalls Harrison's satisfaction after this visit, and suggests: "George's new album was better than anything John had ever done, and [Lennon] knew that as well."[81]

- In author Robert Rodriguez's estimation, "My Sweet Lord" and "Hear Me Lord" are the only other tracks that directly express a religious message.[98] Leng similarly writes of "two key spiritual songs" on an album that focuses on Harrison's "attempt to break free from his Beatles identity".[99]

References

- Williams, p. 153.

- Leng, pp. 62, 83, 319.

- Leng, pp. 71, 83.

- Allison, pp. 46, 47.

- Clayson, pp. 267–68.

- Greene, pp. 70–72, 181, 190.

- Allison, pp. 40, 42–44.

- Greene, pp. 68–69.

- Olivia Harrison, "A Few Words About George", in The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 10.

- Tillery, pp. 58, 107.

- Greene, pp. 80–81, 145.

- Tillery, pp. 58–59, 69, 109.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 36.

- Allison, pp. 47, 122.

- Tillery, p. 89.

- Tillery, pp. 63, 64–65.

- Schaffner, pp. 88–89.

- Greene, p. 97.

- Lavezzoli, p. 195.

- Clayson, pp. 246, 268–69, 439.

- Clayson, p. 267.

- Greene, pp. 157, 158–60.

- Tillery, pp. 72–73.

- Doggett, pp. 89–91.

- Wiener, pp. xvii, 91–92, 113.

- Greene, p. 156.

- Clayson, pp. 256, 266–67.

- Leng, p. 95.

- Greene, p. 190.

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Disc 2; event occurs between 25:28 and 25:40.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 445.

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Disc 2; event occurs between 25:23 and 25:40.

- Harrison, p. 200.

- Allison, pp. 58, 136.

- Creswell, p. 622.

- Leng, p. 71.

- Huntley, p. 59.

- Harrison, front endpapers.

- Inglis, p. 30.

- Allison, pp. 47, 122, 124.

- Stowe, p. 53.

- Harrison, pp. 203–04.

- Planer, Lindsay. "George Harrison 'Awaiting on You All'". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Huntley, pp. 47–48.

- Smith, Howard (3 May 1970). "George Harrison with Howard Smith" (recorded late April 1970). WABC-FM. Event occurs between 29:48 and 30:15.

- Allison, p. 32.

- Harrison, p. 203.

- Allison, p. 55.

- Muster, p. 26.

- Allison, pp. 54–56, 59, 136.

- Harrison, p. 204.

- Tillery, pp. 58, 89.

- Allison, pp. 42, 129.

- Stowe, pp. 53–54.

- Spizer, p. 256.

- Allison, p. 42.

- Inglis, p. 118.

- Tillery, pp. 148, 149.

- Leng, p. 287.

- Rodriguez, pp. 114–15.

- Clayson, pp. 370–71.

- Doggett, p. 115.

- Spizer, p. 28.

- Williams, pp. 137–38.

- Ribowsky, p. 250.

- Ruhlmann, William. "Ike & Tina Turner River Deep – Mountain High". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Williams, pp. 99, 109–10.

- Woffinden, p. 31.

- Williams, pp. 137–38, 153.

- Doggett, p. 117.

- Greene, pp. 169–70, 174.

- Schaffner, p. 138.

- Badman, p. 10.

- Inglis, p. 29.

- Huey, Steve. "The Ronettes". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 431.

- Spizer, pp. 212, 220, 224.

- Leng, pp. 63–64.

- Whitlock, p. 81.

- Whitlock, p. 77.

- Whitlock, pp. 74, 77.

- Harris, pp. 72–73.

- Phil Spector interview, in George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Disc 2; event occurs between 20:54 and 21:13.

- Brown, Mick (30 September 2011). "George Harrison: Fabbest of the Four?". The Daily Telegraph. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 433–34.

- Leng, p. 78.

- Leng, pp. 96, 102.

- Leng, p. 96.

- Clayson, p. 278.

- Spizer, p. 224.

- Spizer, p. 212.

- Leng, p. 82fn.

- Rodriguez, p. 76.

- Harris, p. 72.

- Matovina, p. 90.

- Spizer, p. 219.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 94.

- Rodriguez, p. 148.

- Leng, p. 76.

- Clayson, pp. 294–95.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 40.

- Lavezzoli, p. 186.

- Ribowsky, pp. 182–83.

- Huntley, p. 63.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 427.

- Schaffner, p. 142.

- Gerson, Ben (21 January 1971). "George Harrison All Things Must Pass". Rolling Stone. p. 46. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- DeCurtis, Anthony (12 October 2000). "George Harrison All Things Must Pass". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 August 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Smith, Alan (5 December 1970). "George Harrison: All Things Must Pass (Apple)". NME. p. 2. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Hunt, p. 32.

- Unterberger, Richie. "George Harrison All Things Must Pass". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Woffinden, p. 38.

- Williams, pp. 152–53.

- Ribowsky, p. 255.

- Leng, pp. 95, 96.

- Hunt, p. 22.

- Clayson, pp. 293, 294, 295.

- Snow, p. 25.

- Dimery, pp. 12, 270, 921.

- Dimery, p. 270.

- Unterberger, Richie. "George Harrison Concert for Bangladesh [DVD]". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Badman, pp. 43–44.

- Lavezzoli, pp. 190, 192.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 436–37.

- Spizer, pp. 241, 242.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 438.

- Landau, Jon (3 February 1972). "George Harrison Concert For Bangladesh". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Williams, Richard (1 January 1972). "The Concert for Bangla Desh (album review)". Melody Maker. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Huntley, pp. 304, 308–09.

- A Conversation with George Harrison, Discussing the 30th Anniversary Reissue of "All Things Must Pass" (promotional disc). Interview with Chris Carter (recorded Hollywood, CA, 15 February 2001). Capitol Records. DPRO-7087-6-15950-2-4. Event occurs between 9:06 and 9:21.

- Unterberger, Richie. "George Harrison All Things Must Pass: A Conversation with George Harrison". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- All Things Must Pass (30th Anniversary Edition) EPK. Gnome Records/EMI. 2001.

- All Things Must Pass (30th Anniversary Edition) CD booklet (liner notes by George Harrison). Gnome Records/EMI. 2001.

- All Things Must Pass CD (lyrics insert). Apple Records. 2014.

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World, Disc 2; event occurs between 26:01 and 26:28.

- Leggett, Steve. "George Harrison: Living in the Material World [Video]". AllMusic. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Staunton, Terry (18 May 2012). "Giles Martin on George Harrison's Early Takes, track-by-track". MusicRadar. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "George Harrison Early Takes, Vol. 1". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- "Silver Hawk – Awaiting On You All / All I Can Do". 45cat.com. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Bubbling Under the Hot 100". Billboard. 29 May 1971. p. 59. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "RPM 100 Singles, 26 June 1971". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

Sources

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2006). The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0.

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). George Harrison. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-489-3.

- Creswell, Toby (2006). 1001 Songs: The Great Songs of All Time and the Artists, Stories and Secrets Behind Them. New York, NY: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-915-9.

- Dimery, Robert (ed.) (2010). 1001 Songs You Must Hear Before You Die. New York, NY: Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2089-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone (2002). Harrison. New York, NY: Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-3581-5.

- George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD. Village Roadshow, 2011. (Directed by Martin Scorsese; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair, Martin Scorsese.)

- Greene, Joshua M. (2006). Here Comes the Sun: The Spiritual and Musical Journey of George Harrison. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-12780-3.

- Harris, John (July 2001). "A Quiet Storm". Mojo. pp. 66–74.

- Harrison, George (2002). I, Me, Mine. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-5900-4.

- Hunt, Chris (ed.) (2005). NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980. London: IPC Ignite!.

- Huntley, Elliot J. (2006). Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles. Toronto, ON: Guernica Editions. ISBN 978-1-55071-197-4.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). The Words and Music of George Harrison. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-2819-3.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Matovina, Dan (2000). Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger. Frances Glover Books. ISBN 0-9657122-2-2.

- Muster, Nori J. (2001). Betrayal of the Spirit: My Life Behind the Headlines of the Hare Krishna Movement. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06566-2.

- Ribowsky, Mark (2006). He's a Rebel: Phil Spector – Rock and Roll's Legendary Producer. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81471-6.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Snow, Mat (2013). The Beatles Solo: The Illustrated Chronicles of John, Paul, George, and Ringo After The Beatles (Volume 3: George). New York, NY: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-937994-26-6.

- Spizer, Bruce (2005). The Beatles Solo on Apple Records. New Orleans, LA: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-5-9.

- Stowe, David Ware (2011). No Sympathy for the Devil: Christian Pop Music and the Transformation of American Evangelicalism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3458-9.

- Tillery, Gary (2011). Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5.

- Wiener, Jon (1991). Come Together: John Lennon in His Time (Illini books ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06131-8.

- Whitlock, Bobby; with Roberty, Mark (2010). Bobby Whitlock: A Rock 'n' Roll Autobiography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6190-5.

- Williams, Richard (2003). Phil Spector: Out of His Head. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-9864-3.

- Woffinden, Bob (1981). The Beatles Apart. London: Proteus. ISBN 0-906071-89-5.