Thirty Three & 1/3

Thirty Three & 1⁄3 (stylised as Thirty Three & 1/ॐ on the album cover) is the seventh studio album by English musician George Harrison, released in November 1976. It was Harrison's first album release on his Dark Horse record label, the worldwide distribution for which changed from A&M Records to Warner Bros. as a result of his late delivery of the album's master tapes. Among other misfortunes affecting its creation, Harrison suffered hepatitis midway through recording, and the copyright infringement suit regarding his 1970–71 hit song "My Sweet Lord" was decided in favour of the plaintiff, Bright Tunes Music. The album contains the US top 30 singles "This Song" – Harrison's satire on that lawsuit and the notion of plagiarism in pop music – and "Crackerbox Palace". Despite the problems associated with the album, many music critics recognised Thirty Three & 1⁄3 as a return to form for Harrison after his poorly received work during 1974–75, and considered it his strongest collection of songs since 1970's acclaimed All Things Must Pass.

| Thirty Three & 1⁄3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 19 November 1976 | |||

| Recorded | 24 May–13 September 1976 | |||

| Studio | FPSHOT, Oxfordshire | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:15 | |||

| Label | Dark Horse | |||

| Producer | George Harrison, assisted by Tom Scott | |||

| George Harrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Thirty Three & 1⁄3 | ||||

| ||||

Harrison recorded Thirty Three & 1⁄3 at his Friar Park home studio, with production assistance from Tom Scott. Other musicians on the recording include Billy Preston, Gary Wright, Willie Weeks, David Foster and Alvin Taylor. Harrison undertook extensive promotion for the album, which included producing comedy-themed video clips for three of the songs, two of which were directed by Monty Python member Eric Idle, and making a number of radio and television appearances. Among the latter was a live performance with singer-songwriter Paul Simon on NBC-TV's Saturday Night Live. The album was remastered in 2004 as part of the Dark Horse Years 1976–1992 reissues following Harrison's death in 2001.

Background

In May 1974, George Harrison signed a five-year distribution agreement for Dark Horse Records with A&M Records. In addition to other Dark Horse artists, the contract called for four solo albums from Harrison, the first of which was due by 26 July 1976, following the expiration of the Beatles' recording contract with EMI in January that year.[1] Harrison spent the early part of 1976 involved in activities other than music-making. Foremost among these was the court case, in New York, for a long-running plagiarism suit launched against him by music publisher Bright Tunes, who contended that Harrison had infringed on their copyright of the Chiffons' song "He's So Fine" in his 1970–71 hit single "My Sweet Lord".[2] While in Los Angeles in February and March, Harrison worked on a proposed documentary film of his 1974 North American tour with Ravi Shankar.[3] Also around this time, he made a guest appearance on stage with comedians Monty Python, one of whom, Michael Palin, later recalled that Harrison looked "tired and ill"; author Peter Doggett attributes Harrison's poor health to a lifestyle increasingly reliant on alcohol and cocaine, following the failure of his marriage to Pattie Boyd in 1974.[4]

After beginning sessions for the album in late May,[5] Harrison was struck down with hepatitis and unable to work for much of the summer.[6] With the help of his partner Olivia Arias – who consulted natural remedies such as acupuncture[7] after Harrison had failed to respond to more conventional medical treatment[8] – he regained his health towards the end of the summer.[6] Harrison later said: "I needed the hepatitis to quit drinking."[9] The title for the new album reflected his age at the time of recording, as well as the speed at which the vinyl LP would play on a turntable.[10]

Recording

Harrison started recording Thirty Three & 1⁄3 on 24 May 1976, at his Friar Park home studio, FPSHOT.[5] He had taped the basic tracks for twelve songs[11] before the onset of his bout of hepatitis.[6] Having admitted in a recent interview with Melody Maker that he would prefer to work with a co-producer in future,[12] Harrison enlisted jazz saxophonist and arranger Tom Scott to provide production assistance on the new album.[13][14]

As part of an all-American line-up of musicians at the sessions, other participants included bassist Willie Weeks, drummer Alvin Taylor, keyboard players Richard Tee and David Foster, and jazz percussionist Emil Richards.[15] Harrison's regular associates Gary Wright and Billy Preston also contributed, on keyboards,[16] the latter in between his commitments to the Rolling Stones' concurrent European tour.[6] According to authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter, one of the few items of recording Harrison was able to do over the summer months was an overdubbed acoustic guitar solo on the ballad "Learning How to Love You".[6]

Harrison selected ten of the original twelve tracks for overdubbing.[11] He later said that "See Yourself", which he had started writing in 1967,[17] was a song that he came to like more and more as further instruments were added onto the initial recording.[18] "Woman Don't You Cry for Me" and "Beautiful Girl" were other compositions dating from the late 1960s that Harrison revisited for Thirty Three & 1⁄3;[19] the first of these was a tune he wrote while on tour with Delaney & Bonnie, to showcase his then-recent adoption of slide guitar.[20] Like "See Yourself", "Dear One" was inspired by Paramhansa Yogananda,[21] author of Autobiography of a Yogi and a profound influence on Harrison since his visit to India in September 1966.[22]

Among other new compositions, "This Song" was Harrison's sardonic send-up of the "My Sweet Lord"/"He's So Fine" court case.[23] "Crackerbox Palace" was a song he wrote after meeting the manager of comedian Lord Buckley in January 1976,[24] while "Pure Smokey" was Harrison's musical tribute to soul singer Smokey Robinson.[25] "It's What You Value" – which came about after drummer Jim Keltner had declined payment for appearing in Harrison's 1974 tour band, instead requesting a new Mercedes sportscar[26] – reflected the singer's growing interest in Formula 1,[27] with the lyric's reference to the six-wheel Tyrrell P34.[28][29] As a rare cover version, Harrison recorded a pop arrangement of the Cole Porter standard "True Love",[30] later joking that singer Bing Crosby had "got the chords wrong" in his 1956 original of the song.[3]

After the enforced lay-off until late in the summer, Harrison completed work on the album on 13 September 1976.[31]

Release

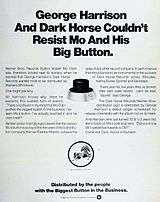

By mid 1976, A&M Records were concerned that Dark Horse's roster of artists – which included Shankar, Stairsteps and little-known groups such as Splinter and Jiva[32] – had failed to provide a return on the company's investment from the past two years.[33] A&M decided to offload the label and, in an attempt to recoup its costs, the company sued Harrison for $10 million in September 1976, citing his late delivery of Thirty Three & 1⁄3.[9][34] That same month, New York judge Richard Owen ruled on the copyright infringement suit,[35] stating that Harrison had "subconsciously plagiarised" part of the melody to the Chiffons song in his 1970 composition.[36] Having settled with A&M by returning his personal advance,[34] Harrison moved Dark Horse over to Mo Ostin-run Warner Bros. Records,[16] where his friend Derek Taylor held an executive position.[37][38] Thirty Three & 1⁄3 and its lead single, "This Song", were both released that November.[39]

Thirty Three & 1⁄3 outsold Dark Horse and Extra Texture in America,[33][40] where it peaked at number 11[41] on its way to being certified gold by the RIAA and selling around 800,000 copies.[42] In Britain, the album made it to number 35.[43] While the singles "This Song" and "Crackerbox Palace" both became US hits, peaking at number 25 and 19, respectively, on the Billboard Hot 100,[41] none of the three singles issued in the UK – "This Song", "True Love" and "It's What You Value" – placed on the national chart, then a top 50.[44] Music journalist Paul Du Noyer later wrote of the contrasting reception: "Punk rock rendered Harrison obsolete in his homeland but US radio warmed to the expertise and tunefulness of it all."[45]

In 2004, Thirty Three & 1⁄3 was remastered and reissued, both separately and as part of the deluxe box set The Dark Horse Years 1976–1992,[46] with the addition of a bonus track, "Tears of the World".[47] The latter was an outtake from the 1980 sessions for Harrison's album Somewhere in England.[48]

Album promotion

Harrison undertook extensive promotion for Thirty Three and 1⁄3,[49] the first time he had done so for one of his albums.[50] His activities included print, radio and television interviews, across selected cities in the United States,[51][52] before moving on to Britain, Germany and the Netherlands.[6] On 20 November 1976, Harrison made an appearance with Paul Simon as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live; the duo performed "Here Comes the Sun" and "Homeward Bound" together on the program.[53] This performance of "Homeward Bound" was later included on the 1990 charity album Nobody's Child: Romanian Angel Appeal,[54] and it is also found on the bonus DVD accompanying Simon's 2007 compilation The Essential Paul Simon.[55]

In addition, Harrison made promotional clips, all in a comical vein,[15] for "This Song", "Crackerbox Palace" and "True Love".[56] The first of these was directed by Harrison and shot at a Los Angeles courthouse,[57] with guest appearances by his musician friends Jim Keltner and Ron Wood.[58] Eric Idle directed the clips for "Crackerbox Palace"[59] and "True Love",[27] both of which were filmed at Friar Park.[60] The clips for "This Song" and "Crackerbox Palace" were featured on the episode of Saturday Night Live when Harrison and Simon performed together.[61]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews

After the disappointments of Dark Horse and Extra Texture over 1974–75, Thirty Three & 1⁄3 was widely viewed as a return to form for Harrison.[62] The new album earned the artist his strongest reviews since All Things Must Pass (1970).[63]

Billboard magazine described the release as "a sunny, upbeat album of love songs and cheerful jokes that is his happiest and most commercial package, with least high-flown postures, for perhaps his entire solo career". The reviewer rated the production "top-notch" before concluding: "And Harrison's often-spectacular melody writing gift gets brilliant display here."[64] In Melody Maker, Ray Coleman remarked on Warner Bros.' need to re-establish Harrison, adding: "The question is merely whether the music [on Thirty Three & 1⁄3] merits it. Unequivocally, the answer is yes." Coleman praised Harrison's vocals on this "fine album" and likened the quality of his melodies to that on the Beatles' 1965 album Rubber Soul.[65] Michael Gross wrote in Swank magazine that Harrison "seems with 33 1/3 to have come unstuck", adding: "If the new record company, new girlfriend ... Olivia Arias, and new disc have put him in a more secure place in the material world, he could well recapture his spot as the Beatle to watch."[66] In a review that author Michael Frontani terms "particularly laudatory", Richard Meltzer of The Village Voice described Harrison's new work as "his best LP since All Things Must Pass and on par with, say, [Bob Dylan's] Blood on the Tracks".[67] Fellow Village Voice critic Robert Christgau gave the record a B-minus and said, "This isn't as worldly as George wants you to think--or as he thinks himself, for all I know--but it ain't fulla shit either." He highlighted "This Song" and the album's second side, particularly "Crackerbox Palace", which he regarded among Harrison's best songs since his Beatles days.[68]

Less impressed, Rolling Stone continued to regard Harrison in an unfavourable light after what Elliot Huntley terms its "volte-face" in 1974.[69] The magazine's reviewer, Ken Tucker, noted the accessibility of "fast, cheerful numbers" such as "Woman Don't You Cry for Me" and "This Song" but lamented both "George's persistent preaching" elsewhere and that Scott's presence rendered the album as "music with the feeling and sincerity of cellophane".[70] NME critic Bob Woffinden admired Harrison's guitar playing but dismissed him as a lyric writer, before concluding: "Harrison's general demeanour is more encouraging ... While it is an album of no particular merit in itself, it is one which leads me to believe that his best work may not necessarily be behind him."[71][72] Four years later, however, Woffinden offered a more positive assessment, writing that "His spiritual convictions no longer seemed to be cramping his style, but affording him a generous and open heart. An excellent production and frequently inspired guitar work were amongst the other positive qualities which the album could boast."[73]

Writing in 1977, Nicholas Schaffner found that, in comparison with All Things Must Pass, the songs on Thirty Three & 1⁄3 "rely on pure melody and George's own musicianship instead of dazzling orchestrations and production". Schaffner added: "The tastefulness of his performance on his two pet instruments, slide guitar and synthesizer, is unmatched in rock, and Thirty-three and a Third boasts the most varied and tuneful collection of Harrison melodies to date."[59]

In the 1978 edition of a book that traditionally promoted an unfavourable view on Harrison's work, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record,[74] authors Roy Carr and Tony Tyler described Thirty Three & 1⁄3 as Harrison's "best effort – by far" since All Things Must Pass.[75] Carr and Tyler concluded: "It must be the production. For no individual track really presents itself as typifying a New Harrison Approach – and yet the impression left by the album as a whole is definitely of a more balanced, poised and devil-may-care Hari ..."[76]

Retrospective reviews and legacy

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| All-Music Guide to Rock | |

| Blender | |

| Elsewhere | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Mojo | |

| Music Story | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | 7/10[84] |

In a review for Rolling Stone following Harrison's death in November 2001, Greg Kot said of Thirty Three & 1⁄3: "'Crackerbox Palace' has a twinkle in its eye, the kind of song that had previously eluded the increasingly self-serious Harrison ... The tune's melodic sweep is nearly matched by 'This Song' ... The two tracks form the center of the guitarist's strongest collection since his solo debut."[85] Having interviewed Harrison for Guitar World magazine in 1987, Rip Rense praised the solos on tracks such as "Learning How to Love You" and "Beautiful Girl", while opining of Harrison's "underrated solo [career]": "his work is my choice for best among the ex-Fabs for being the most substantial in melody, structure, and content. Thirty-Three and a Third, for instance, might yet be hailed as a minor masterpiece ..."[86]

In the 2004 Rolling Stone Album Guide, Mac Randall named "Beautiful Girl" as "one of the many highlights of his upbeat return to pop form, Thirty-Three & 1/3".[87] Writing for The Word that year, Paul Du Noyer referred to the album as "the lost treasure" among Harrison's Dark Horse Years reissues,[88] and in a concurrent review for Blender, he highlighted "Crackerbox Palace" and "Learning How to Love You" as the standout tracks.[45] In another 2004 appraisal, for PopMatters, Jason Korenkiewicz wrote that the remaster "allows the guitars to ring, and the percussion has a crispness that was hidden in past releases". Korenkiewicz included "the magnificent 'Dear One'" among the album's "countless classic tracks" and considered that Thirty Three & 1⁄3 "features more consistent high points than any Harrison album since All Things Must Pass".[89] Conversely, Kit Aiken of Uncut described it as an "oddly ordinary album" that reflected the "blow to his confidence and inspiration" as a result of the court's ruling on "My Sweet Lord".[90] Writing for the same magazine in July 2012, David Quantick included Thirty Three & 1⁄3 among Harrison's best solo releases, along with All Things Must Pass and Cloud Nine.[84]

Robert Rodriguez has written of A&M's folly in parting with Dark Horse Records and thereby missing out on a work that would stand as "possibly [Harrison's] most commercial ever".[91] Rodriguez adds: "If ever an album cried out for a tour, it was this lively, energetic, and colorfully upbeat collection."[92] Former Mojo editor Mat Snow views it as a "confident, if not quite classic" album on which Harrison "had his groove back",[40] while New Zealand Herald critic Graham Reid writes that Harrison got off to "a flying start" on his new label and he notes the consistent quality across the album, which includes "a more than decent treatment of Cole Porter's True Love".[79] In his review of Harrison's 2014 Apple/EMI reissues, Alex Franquelli of PopMatters cites Thirty Three & 1⁄3 as an example of how "Harrison's artistic output remained coherent with itself" following All Things Must Pass, and he describes the album as "well above the average pop songwriting".[93]

Track listing

All songs written by George Harrison, except where noted.

- Side one

- "Woman Don't You Cry for Me" – 3:18

- "Dear One" – 5:08

- "Beautiful Girl" – 3:39

- "This Song" – 4:13

- "See Yourself" – 2:51

- Side two

- "It's What You Value" – 5:07

- "True Love" (Cole Porter) – 2:45

- "Pure Smokey" – 3:56

- "Crackerbox Palace" – 3:57

- "Learning How to Love You" – 4:13

- Bonus tracks

For the 2004 digitally remastered issue of Thirty Three & 1⁄3, a bonus track was added:

- "Tears of the World" – 4:04

iTunes bonus track:

- "Learning How to Love You (Early Mix)" – 4:13

Personnel

The following personnel are credited in the liner notes.[94]

- George Harrison – vocals, electric and acoustic guitars, synthesizers, percussion, backing vocals

- Tom Scott – saxophones, flute, lyricon

- Richard Tee – piano, organ, Fender Rhodes

- Willie Weeks – bass

- Alvin Taylor – drums

- Billy Preston – piano, organ, synthesizer

- David Foster – Fender Rhodes, clavinet

- Gary Wright – keyboards

- Emil Richards – marimba

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[104] | Gold | 500,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[105] | Silver | 60,000^ |

|

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

References

- John Sippel, "A&M + Harrison: Pact That Failed", Billboard, 11 December 1976, pp. 6, 53 (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- Huntley, pp. 130–32.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 453.

- Doggett, p. 250.

- Badman, p. 186.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 454.

- Tillery, p. 117.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 133.

- Clayson, p. 359.

- Rodriguez, p. 169.

- A Personal Music Dialogue at Thirty Three & ⅓ interview album (Dark Horse Records, 1976; DH PRO 649).

- Badman, p. 176.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 453–54.

- Leng, p. 191.

- Rodriguez, p. 170.

- Leng, p. 190.

- Harrison, p. 108.

- Giuliano, pp. 223, 224.

- Rodriguez, pp. 170–71.

- Clayson, pp. 279–80.

- Inglis, pp. 60, 62.

- Tillery, pp. 56, 117–18.

- Leng, p. 193.

- Clayson, p. 358.

- Inglis, p. 63.

- Huntley, p. 147.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 455.

- Harrison, p. 322.

- Clayson, p. 367.

- Huntley, p. 148.

- Badman, pp. 186, 194.

- Rodriguez, pp. 197–98, 247.

- Woffinden, p. 103.

- Doggett, p. 251.

- Huntley, pp. 132–33, 143.

- Badman, p. 191.

- Woffinden, pp. 102–03.

- Clayson, p. 396.

- Badman, pp. 197, 198.

- Snow, p. 58.

- "George Harrison Thirty Three & 1/3: Awards", AllMusic (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- Schaffner, pp. 192, 195.

- "George Harrison" > Albums, Official Charts Company (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- Huntley, p. 150.

- Paul Du Noyer, "Back Catalogue: George Harrison", Blender, April 2004, pp. 152–53.

- Stephen Thomas Erlewine, "George Harrison The Dark Horse Years 1976–1992", AllMusic (retrieved 22 August 2014).

- Allison, p. 156.

- Leng, pp. 213–14.

- Schaffner, pp. 192–93.

- Clayson, p. 360.

- Schaffner, p. 193.

- Clayson, pp. 360–62.

- Badman, p. 198.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 456.

- Listing: "Paul Simon – The Essential Paul Simon", Discogs (received 22 August 2014).

- Badman, p. 196.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 132.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 454–55.

- Schaffner, p. 192.

- Leng, pp. 195, 196.

- "Words of Innespriation: The Lyrics and Unplanned Career of Neil Innes". NeilInnes.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Carol Clerk, "George Harrison", Uncut, February 2002; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required; retrieved 23 July 2014).

- Schaffner, pp. 182, 192.

- Nat Freedland (ed.), "Top Album Picks", Billboard, 5 December 1976, p. 58 (retrieved 14 October 2013). From the magazine's reviews key: "Spotlight: the most outstanding of the week's releases".

- Ray Coleman, "Harrison Regains His Rubber Soul", Melody Maker, 27 November 1976, p. 23.

- Michael Gross, "George Harrison: The Zoned-Out Beatle Turns 33 1/3", Swank, May 1977; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Frontani, p. 161.

- Christgau, Robert (27 December 1976). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Huntley, pp. 112, 128–29, 145.

- Ken Tucker, "George Harrison Thirty Three & 1/3", Rolling Stone, 13 January 1977; quoted in "George Harrison – Thirty-Three & 1/3", superseventies.com (retrieved 8 March 2015).

- Bob Woffinden, "George Harrison: Thirty-Three & 1/3", NME, 27 November 1976, p. 36; available at Rock's Backpages (retrieved 17 July 2014).

- Hunt, p. 111.

- Woffinden, pp. 100, 103.

- David Quantick, "George Harrison – Let It Roll: Songs By George Harrison", uncut.co.uk, June 2009 (retrieved 24 July 2014).

- Carr & Tyler, p. 120.

- Carr & Tyler, pp. 120–21.

- William Ruhlmann, "George Harrison Thirty Three & 1/3", AllMusic (retrieved 30 January 2016).

- Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine, p. 181.

- Graham Reid, "George Harrison (2011): Ten years after, a dark horse reconsidered" > "Thirty-Three and a Third", Elsewhere, 22 November 2011 (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- Larkin, p. 2650.

- John Harris, "Beware of Darkness", Mojo, November 2011, p. 82.

- Pricilia Decoene, "Critique de Thirty Three And A Third, George Harrison" (in French), Music Story (archived version from 6 October 2015, retrieved 29 December 2016).

- "George Harrison: Album Guide", rollingstone.com (archived version retrieved 5 August 2014).

- David Quantick, "George Harrison – The Dark Horse's post-Fabs highlights", Uncut, July 2012, p. 93.

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, p. 188.

- Rip Rense, "There Went the Sun: Reflection on the Passing of George Harrison", Beatlefan, 29 January 2002 (retrieved 14 December 2014).

- Brackett & Hoard, p. 368.

- Paul Du Noyer, "George Harrison: Thirty Three & ⅓; George Harrison; Somewhere In England; Gone Troppo; Cloud Nine; Live In Japan", The Word, April 2004.

- Jason Korenkiewicz, "Review: The Dark Horse Years 1976–1992", PopMatters, 3 May 2004 (retrieved 5 January 2014).

- Kit Aiken, "All Those Years Ago: George Harrison The Dark Horse Years 1976–1992", Uncut, April 2004, p. 118.

- Rodriguez, pp. 169–70.

- Rodriguez, p. 171.

- Alex Franquelli, "George Harrison: The Apple Years 1968–75", PopMatters, 30 October 2014 (retrieved 1 November 2014).

- Thirty Three & 1/3 (CD booklet). George Harrison. Dark Horse Records. 2004. p. 9.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- "RPM Top Albums: February 12, 1977" Archived 5 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 25 May 2015).

- Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- "George Harrison – Thirty-Three & 1/3", norwegiancharts.com (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- "George Harrison – Thirty-Three & 1/3", swisscharts.com (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- "Cash Box Top 100 Albums", Cash Box, 15 January 1977, p. 53.

- "Highest position and charting weeks of 33 1/3 by George Harrison". oricon.co.jp. Oricon Style. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- "RPM Top 100 Albums of '77", Library and Archives Canada (retrieved 25 May 2015).

- "Pop Albums (Year-End)", Billboard, 24 December 1977, p. 66 (retrieved 4 March 2015).

- "American album certifications – George Harrison – Thirty Three and A Third". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 10 October 2012. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

- "British album certifications – George Harrison – Thirty Three and A Third". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 10 October 2012. Select albums in the Format field. Select Silver in the Certification field. Type Thirty Three and A Third in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

Sources

- Dale C. Allison Jr., The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Vladimir Bogdanov, Chris Woodstra & Stephen Thomas Erlewine (eds), All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music (4th edn), Backbeat Books (San Francisco, CA, 2001; ISBN 0-87930-627-0).

- Nathan Brackett & Christian Hoard (eds), The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th edn), Fireside/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2004; ISBN 0-7432-0169-8).

- Roy Carr & Tony Tyler, The Beatles: An Illustrated Record, Trewin Copplestone Publishing (London, 1978; ISBN 0-450-04170-0).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- The Editors of Rolling Stone, Harrison, Rolling Stone Press/Simon & Schuster (New York, NY, 2002; ISBN 0-7432-3581-9).

- Michael Frontani, "The Solo Years", in Kenneth Womack (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-139-82806-2), pp. 153–82.

- Geoffrey Giuliano, Dark Horse: The LIfe and Art of George Harrison, Da Capo Press (Cambridge, MA, 1997; ISBN 0-306-80747-5).

- Gary Graff & Daniel Durcholz (eds), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Visible Ink Press (Farmington Hills, MI, 1999; ISBN 1-57859-061-2).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Chris Hunt (ed.), NME Originals: Beatles – The Solo Years 1970–1980, IPC Ignite! (London, 2005).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Colin Larkin, The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th edn), Omnibus Press (London, 2011; ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980, Backbeat Books (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Mat Snow, The Beatles Solo: The Illustrated Chronicles of John, Paul, George, and Ringo After The Beatles (Volume 3: George), Race Point Publishing (New York, NY, 2013; ISBN 978-1-937994-26-6).

- Gary Tillery, Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison, Quest Books (Wheaton, IL, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5).

- Bob Woffinden, The Beatles Apart, Proteus (London, 1981; ISBN 0-906071-89-5).