Aviation in Australia

Aviation in Australia began in the 1920s with the formation of Qantas, which became the flag carrier of Australia. The Australian National Airways was the predominant domestic carrier from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s. After World War II, Qantas was nationalised and its domestic operations were transferred to Trans Australia Airlines (TAA) in 1946. The Two Airlines Policy was formally established in 1952 to ensure the viability of both airlines. However, ANA's leadership was quickly eroded by TAA, and it was acquired by Ansett Transport Industries in 1957. The duopoly continued for the next four decades. In the mid-1990s TAA was merged with Qantas and later privatised. Ansett collapsed in September 2001. In the following years, Virgin Australia became a challenger to Qantas. Both companies launched low-cost subsidiaries Jetstar and Tigerair Australia, respectively.

Overseas flights from Australia to Europe via the Eastern Hemisphere are known as the Kangaroo Route, whereas flights via the Western Hemisphere are known as the Southern Cross Route. Qantas began international passenger flights in May 1935. In 1954, the first flight from Australia to North America was completed, as a 60-passenger Qantas aircraft connected Sydney with San Francisco and Vancouver, having fuel stops at Fiji, Canton Island and Hawaii. In 1982, a Pan Am first flew non-stop from Los Angeles to Sydney. A non-stop flight between Australia and Europe was first completed in March 2018 from Perth to London.

History

Until World War II

In 1934, Qantas and Britain's Imperial Airways (a forerunner of British Airways) formed a new company, Qantas Empire Airways Limited (QEA),[1] which commenced operations in December 1934, flying between Brisbane and Darwin. QEA flew internationally from May 1935, when the service from Darwin was extended to Singapore, and Imperial Airways operated the rest of the service through to London.[2] Australian National Airways (ANA) was established in 1936 by a consortium of British-financed Australian shipowners.

Until World War II, Australia had been one of the world's leading centres of aviation. With its tiny population of about seven million, Australia ranked sixth in the world for scheduled air mileage, had 16 airlines, was growing at twice the world average, and had produced a number of prominent aviation pioneers, including Lawrence Hargrave, Harry Hawker, Bert Hinkler, Lawrence Wackett, the Reverend John Flynn, Sidney Cotton, Keith Virtue and Charles Kingsford Smith. Governments on both sides of politics, well aware of the immense stretches of uninhabitable desert that separated the small productive regions of Australia, regarded air transport as a matter of national importance. In the words of Arthur Brownlow Corbett, Director General of Civil Aviation:

A nation which refuses to use flying in its national life must necessarily today be a backward and defenceless nation.[3]

Air transport was encouraged both with direct subsidies and with mail contracts. Immediately before the start of the war, more than half of all airline passenger and freight miles were subsidised.

However, after 1939 and especially after Japan's invasion of the islands to the north in 1941, civil aviation was sacrificed to military needs. During the war, most of the Qantas fleet of ten was taken over by the Australian government for war service and enemy action and accidents destroyed half of the fleet.[4]

Post World War II

By the end of the Second World War, there were only nine domestic airlines remaining, eight smaller regional concerns and Australian National Airways (ANA), a conglomerate owned by British and Australian shipping interests which had a virtual monopoly on the major trunk routes and received 85% of all government air transport subsidies.

The Chifley Government's view was summed up by Minister for Air, Arthur Drakeford: Where are the great pioneers of aviation? ..... We discover that one by one the small pioneer enterprises are disappearing from the register. It is the inevitable process of absorption by a monopoly. Air transport, the government believed, was primarily a public service, like hospitals, the railways or the post office. If there was to be a monopoly at all, then it should be one owned by the public and working in the public interest.

In August 1945, only two days after the end of World War II, the Australian parliament passed the Australian National Airways Bill, which set up the Australian National Airways Commission (ANAC) and charged it with the task of reconstructing the nation's air transport industry. In keeping with the Labor government's socialist leanings, the bill declared that licences of private operators would lapse for those routes that were adequately serviced by the national carrier. From this time on, it seemed, air transport in Australia would be a government monopoly. However, a legal challenge (Australian National Airways Pty Ltd v Commonwealth), backed by the Liberal opposition and business interests generally, was successful and in December 1945, the High Court ruled that the Commonwealth did not have the power to prevent the issue of airline licences to private companies. The government could set up an airline if it wished, but it could not legislate a monopoly. Much of the press objected strongly to the setting up of a public airline network, seeing it as a form of socialisation by stealth.

The bill was suitably amended to remove the monopoly provisions, and ANAC came into existence in February 1946. ANAC formed Trans Australia Airlines (TAA) in 1946, and nationalised Qantas in 1947. Qantas's domestic operations, in Queensland, were transferred to TAA, while Qantas continued as an international airline. Shortly later, QEA began its first services outside the British Empire, to Tokyo,[5] and services to Hong Kong began around the same time.

Two Airlines Policy

However, ANA's leadership in Australia's aviation was quickly being eroded by TAA, so in 1952, the Menzies Government formally established the "Two Airlines Policy", to ensure the viability of both major airlines, the government-owned TAA and the privately owned ANA. In reality, it ensured the survival of the private airline ANA.

Under the policy, only two airlines were allowed to operate flights between state capital cities and major regional city airports. The Two Airlines Policy was in fact a legal barrier to new entrants to the Australian aviation market. It restricted intercapital services to the two major domestic carriers. This anti-competitive arrangement ensured that they carried approximately the same number of passengers, charged the same fares and had similar fleet sizes and equipment.

Ivan Holyman, managing director of ANA and its main driving force, died in 1957. The five British shipping companies that owned the airline had been trying to get out for several years, and offered to sell out to the government, in order that ANA merge with TAA and some smaller airlines.[6] The government declined. Later that year, ANA was acquired by the much smaller Ansett Airways, and the duopoly would continue for the next four decades.

Deregulation

Deregulation of aviation in Australia commenced in the late 1980s.

In 1986 Trans-Australia Airlines was renamed Australian Airlines,[7] which merged in September 1992 with Qantas. Qantas was gradually privatised between 1993 and 1997.[8][9][10] The legislation allowing privatisation requires Qantas to be at least 51% owned by Australian shareholders.

In 1988, the Australian Government formed the Federal Airports Corporation (FAC), placing 22 airports around the nation under its operational control. In April 1994, the Government announced that all airports operated by FAC would be privatised in several phases.[11]

Virgin Australia was launched as Virgin Blue in August 2000. The timing of Virgin Blue's entry into the Australian market was fortuitous as it was able to fill the vacuum created by the collapse of Ansett Australia in September 2001. In the following years, Virgin Australia became a challenger to Qantas. Both companies launched low-cost subsidiaries: Qantas formed Jetstar in 2003 and Virgin acquired Tigerair Australia in 2013.

Statistics

Top 30 routes by annual passenger numbers

| Rank | City 1 | City 2 | Distance (km) | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 707 | 7,008,000 | 7,088,600 | 7,901,100 | 7,727,500 | 8,047,700 | 8,244,000 | 8,316,900 | 8,613,400 | 8,904,700 | 9,097,100 | ||

| 2 | 752 | 4,306,500 | 4,295,800 | 4,397,500 | 4,406,000 | 4,390,700 | 4,425,100 | 4,448,100 | 4,476,200 | 4,658,100 | 4,736,300 | ||

| 3 | 1379 | 2,688,500 | 2,706,200 | 3,020,200 | 3,090,400 | 3,189,600 | 3,198,800 | 3,317,100 | 3,353,800 | 3,493,300 | 3,541,100 | ||

| 4 | 679 | 2,164,800 | 2,148,000 | 2,405,000 | 2,244,800 | 2,440,600 | 2,559,100 | 2,595,200 | 2,618,300 | 2,704,400 | 2,740,700 | ||

| 5 | 642 | 2,122,700 | 2,103,800 | 2,271,400 | 2,186,700 | 2,085,200 | 2,195,100 | 2,272,000 | 2,311,000 | 2,393,900 | 2,456,400 | ||

| 6 | 2705 | 1,772,200 | 1,724,900 | 1,736,400 | 1,855,900 | 2,130,700 | 2,290,700 | 2,160,700 | 2,138,900 | 2,072,900 | 2,033,200 | ||

| 7 | 1328 | 1,673,500 | 1,615,800 | 1,767,600 | 1,671,300 | 1,790,700 | 1,675,400 | 1,754,000 | 1,812,300 | 1,966,100 | 2,012,600 | ||

| 8 | 1167 | 1,589,100 | 1,600,200 | 1,785,700 | 1,722,700 | 1,751,200 | 1,751,900 | 1,813,000 | 1,831,500 | 1,872,000 | 1,898,300 | ||

| 9 | 3285 | 1,493,200 | 1,465,100 | 1,622,700 | 1,731,700 | 1,811,400 | 1,800,400 | 1,798,900 | 1,760,900 | 1,753,700 | 1,716,500 | ||

| 10 | 616 | 1,157,800 | 1,202,300 | 1,231,900 | 1,157,900 | 1,239,100 | 1,388,800 | 1,400,100 | 1,493,600 | 1,555,500 | 1,630,300 | ||

| 11 | 1387 | 1,196,500 | 1,154,800 | 1,153,800 | 1,108,000 | 1,187,000 | 1,199,600 | 1,256,100 | 1,307,000 | 1,346,900 | 1,377,900 | ||

| 12 | 470 | 1,068,500 | 1,093,800 | 1,038,000 | 1,065,200 | 1,003,100 | 994,500 | 972,300 | 984,200 | 1,026,100 | 1,133,000 | ||

| 13 | 1967 | 940,300 | 832,900 | 876,800 | 894,300 | 933,900 | 978,600 | 1,000,900 | 1,032,600 | 1,115,300 | 1,129,300 | ||

| 14 | 3615 | 683,400 | 718,000 | 755,100 | 867,500 | 951,500 | 1,017,700 | 1,062,000 | 1,007,800 | 984,100 | 969,100 | ||

| 15 | 1110 | 968,700 | 942,600 | 941,100 | 977,400 | 994,200 | 957,500 | 948,200 | 965,300 | 976,600 | 960,200 | ||

| 16 | 237 | 959,500 | 1,021,800 | 1,096,200 | 1,069,100 | 1,053,200 | 1,027,600 | 968,200 | 946,800 | 959,400 | 949,200 | ||

| 17 | 476 | 842,900 | 832,800 | 838,200 | 790,500 | 835,800 | 872,800 | 878,300 | 880,500 | 918,000 | 923,200 | ||

| 18 | 1621 | 660,300 | 637,000 | 717,100 | 679,800 | 729,200 | 747,500 | 776,700 | 792,800 | 830,300 | 849,600 | ||

| 19 | 2305 | 482,200 | 389,800 | 451,100 | 504,800 | 581,700 | 677,600 | 711,800 | 770,600 | 823,400 | 841,300 | ||

| 20 | 795 | 727,100 | 735,900 | 798,000 | 908,900 | 964,900 | 863,500 | 746,400 | 696,400 | 678,500 | 697,900 | ||

| 21 | 1038 | 458,700 | 490,300 | 502,800 | 472,800 | 477,900 | 517,200 | 536,400 | 546,300 | 616,600 | 655,900 | ||

| 22 | 2120 | 577,600 | 626,000 | 599,000 | 592,500 | 621,700 | 624,300 | 616,400 | 611,000 | 617,100 | 614,100 | ||

| 23 | 954 | 609,500 | 604,500 | 612,700 | 620,500 | 605,400 | 583,000 | 560,200 | 558,200 | 576,100 | 594,300 | ||

| 24 | 613 | 529,300 | 564,300 | 579,100 | 582,200 | 591,800 | 583,700 | 570,300 | 543,700 | 574,000 | 590,700 | ||

| 25 | 835 | 477,600 | 446,700 | 460,300 | 475,100 | 463,300 | 464,600 | 464,100 | 481,800 | 539,800 | 582,700 | ||

| 26 | 517 | 569,600 | 600,600 | 643,900 | 606,400 | 644,400 | 636,100 | 612,600 | 587,800 | 563,800 | 522,100 | ||

| 27 | 1452 | 452,100 | 412,300 | 403,200 | 382,000 | 324,600 | 392,200 | 397,600 | 406,000 | 441,800 | 485,800 | ||

| 28 | 835 | 416,800 | 369,000 | 370,700 | 429,700 | 425,200 | 437,500 | 434,900 | 443,000 | 449,500 | 476,100 | ||

| 29 | 1247 | - | 518,300 | 587,100 | 646,100 | 762,500 | 722,100 | 685,200 | 600,200 | 490,600 | 436,900 | ||

| 30 | 2850 | 341,600 | 381,600 | 367,200 | 366,000 | 367,000 | 375,900 | 391,500 | 396,200 | 407,700 | 406,200 |

Busiest airports

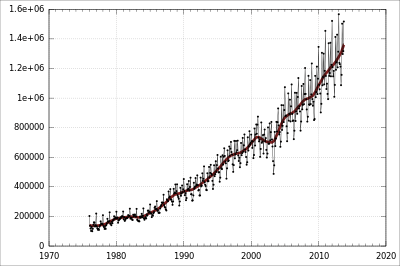

Domestic Airport passenger numbers are calculated by the Department of Infrastructure and Transport and include passenger numbers from the major domestic airlines only; these being Qantas, Virgin Australia, Jetstar Airways and Tiger Australia. Regional Express, QantasLink and similar airlines are considered to be regional airlines and are not included in these figures.

- Monthly

| Rank | Airport | State | Total Mar 2014 | Total Mar 2015 | Monthly Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sydney Airport | 2,154,200 | 2,209,600 | ||

| 2. | Melbourne Airport | 1,974,700 | 2,055,400 | ||

| 3. | Brisbane Airport | 1,402,700 | 1,390,600 | ||

| 4. | Perth Airport | 731,600 | 713,200 | ||

| 5. | Adelaide Airport | 581,300 | 585,100 | ||

| 6. | Gold Coast Airport | 398,100 | 400,000 | ||

| 7. | Cairns Airport | 278,000 | 284,900 | ||

| 8. | Canberra Airport | 250,400 | 252,000 | ||

| 9. | Hobart Airport | 192,300 | 199,200 | ||

| 10. | Darwin Airport | 128,300 | 125,800 |

- Yearly

| Rank | Airport | State | FY 2015-16 | FY 2016-17 | Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sydney Airport | 26,587,000 | 27,077,700 | ||

| 2 | Melbourne Airport | 24,482,700 | 24,996,800 | ||

| 3 | Brisbane Airport | 17,013,200 | 17,102,600 | ||

| 4 | Perth Airport | 8,285,900 | 8,029,500 | ||

| 5 | Adelaide Airport | 6,922,000 | 7,049,200 | ||

| 6 | Gold Coast Airport | 5,256,400 | 5,362,800 | ||

| 7 | Cairns Airport | 4,141,800 | 4,283,300 | ||

| 8 | Canberra Airport | 2,816,000 | 2,932,800 | ||

| 9 | Hobart Airport | 2,312,900 | 2,440,800 | ||

| 10 | Darwin Airport | 1,783,700 | 1,809,400 |

See also

- 1989 Australian pilots' dispute

- List of Australian airports

References

- "The Move to Brisbane". Our Company. Qantas. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- "Venturing Overseas". Our Company. Qantas. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- "ANAC – Beginning of TAA". 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "The World at War". Our Company. Qantas. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- "Post War Expansion". Our Company. Qantas. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- Grant, J. R. A False Dawn? Australian National Airways Air Enthusiast magazine article July–August 1997 No.70 pp. 22–24

- "World airline directory – Qantas Airways". Flight International. 143 (4362): 117. 24–30 March 1993. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- The Hon R. Willis, Answer to a Question without Notice, House of Representatives Debates, 13 May 1993, p.775.

- Commonwealth of Australia Budget Statements 1996–97, Budget Paper no. 3, p. 3-191.

- Ian Thomas, '"Luck" played a key part in float success', Australian Financial Review, 31 July 1995.

- Frost & Sullivan (25 April 2006). "Airport Privatisation". MarketResearch.com. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics (23 March 2018). "Australian Domestic Aviation Activity Annual Publications". Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Australian Domestic Aviation Activity Monthly Publications - Monthly

- Airport traffic data - Yearly