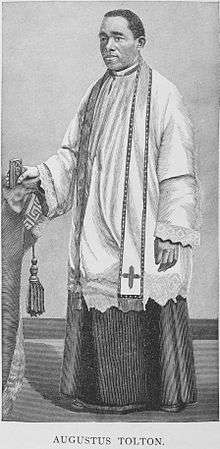

Augustus Tolton

Augustus Tolton (April 1, 1854 – July 9, 1897), baptized Augustine Tolton, was the first Roman Catholic priest in the United States publicly known to be black when he was ordained in 1886. (James Augustine Healy, ordained in 1854, and Patrick Francis Healy, ordained in 1864, were of mixed-race.) A former slave who was baptized and reared Catholic, Tolton studied formally in Rome.

The Reverend Father Augustus Tolton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | April 24, 1886 by Lucido Maria Parocchi |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Augustus Tolton |

| Born | April 1, 1854 Ralls County, Missouri |

| Died | July 9, 1897 (aged 43) Chicago, Illinois |

| Sainthood | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Title as Saint | Venerable |

He was ordained in Rome on Easter Sunday of 1886 at the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran. Assigned to the diocese of Alton (now the Diocese of Springfield), Tolton first ministered to his home parish in Quincy, Illinois. Later assigned to Chicago, Tolton led the development and construction of St. Monica's Catholic Church as a black "national parish church", completed in 1893 at 36th and Dearborn Streets on Chicago's South Side.

Biography

Early life

Augustus Tolton was born in Missouri to Peter Paul Tolton and his wife Martha Jane Chisley, who were enslaved. His mother, who was reared Catholic, named him after an uncle named Augustus. He was baptized Augustine in St. Peter's Catholic Church near Rensselaer, Missouri, a community in northeast Missouri. His master was Stephen Elliott. Savilla Elliot, his master's wife, stood as Tolton's godmother.

Freedom

How the members of the Tolton family gained their freedom remains a subject of debate. According to accounts Tolton told friends and parishioners, his father escaped first and joined the Union Army. Tolton's mother then ran away with her children Samuel, Charley, Augustine, and Anne. With the assistance of sympathetic Union soldiers and police, she crossed the Mississippi River and into the Free State of Illinois.[1] According to descendants of the Elliott family, though, Stephen Elliott freed all his slaves at the outbreak of the American Civil War and allowed them to move North. Augustine's father died of dysentery before the war ended.

Vocation

After arriving in Quincy, Illinois, Martha, Augustus, and Charley began working at the Herris Tobacco Company where they made cigars. After Charley's death at a young age, Augustine met Peter McGirr, an Irish immigrant priest from Fintona, County Tyrone, who gave him the opportunity to attend St. Peter's parochial school during the winter months, when the factory was closed. The priest's decision was controversial in the parish. Although abolitionists were active in the town, many of McGirr's parishioners objected to a black student at their children's school. McGirr held fast and allowed Tolton to study there. Later, Tolton continued studies directly with some priests.

Despite McGirr's support, Tolton was rejected by every American seminary to which he applied. Impressed by his personal qualities, McGirr continued to help him and enabled Tolton's study in Rome. Tolton graduated from St. Francis Solanus College (now Quincy University) and attended the Pontifical Urbaniana University, where he became fluent in Italian language as well as studying Latin and Greek.

Priesthood

Tolton was ordained to the priesthood in Rome in 1886 at age 31.[1] His first public Mass was in St. Peter's Basilica on Easter Sunday in 1886. Expecting to serve in an African mission, he had been studying its regional cultures and languages. Instead, he was directed to return to the United States to serve the black community.

Tolton celebrated his first Mass in the United States at St. Boniface church in Quincy. He attempted to organize a parish there, but over the years met with resistance from both white Catholics (many of whom were ethnic German) and Protestant blacks, who did not want him trying to attract people to another denomination.[1] He organized St. Joseph Catholic Church and school in Quincy, but ran into opposition from the new dean of the parish, who wanted him to turn away white worshipers from his services.

After reassignment to Chicago, Tolton led a mission society, St. Augustine's, which met in the basement of St. Mary's Church. He led the development and administration of the Negro "national parish" of St. Monica's Catholic Church, built at 36th and Dearborn Streets on the South Side, Chicago. The church nave seated 850 parishioners[3] and was built with money from philanthropists Mrs. Anne O'Neill[4] and Katharine Drexel.[5]

St. Monica's Parish grew from 30 parishioners to 600 with the construction of the new church building.[6] Tolton's success at ministering to black Catholics quickly earned him national attention within the Catholic hierarchy.[1][7] "Good Father Gus", as he was called by many, was known for his "eloquent sermons, his beautiful singing voice, and his talent for playing the accordion."[1]

Several contemporaneous news articles describe his personal qualities and importance. An 1893 article in the Lewiston Daily Sun, written while he worked to establish St. Monica's for African American Catholics in Chicago, said, "Father Tolton ... is a fluent and graceful talker and has a singing voice of exceptional sweetness, which shows to good advantage in the chants of the high mass. It is no unusual thing for many white people to be seen among his congregation."[3] Among Chicago’s Catholics, Fr. Tolton found a warm welcome from the Jesuits of Holy Family Church and St. Ignatius College (now St. Ignatius College Prep, 1076 W. Roosevelt Road). They invited him to stay in the Jesuit residence in the 1869 school building and to preach at the High Mass at Holy Family on Jan. 29, 1893. Holy Family was then the largest English-speaking parish in Chicago, composed primarily of Irish immigrants and their children who were also struggling to establish a home in the sometimes unwelcoming city. Fr. Tolton appealed “at all the masses” and collected $500 ($14,000 in 2020) for St. Monica Church, which was dedicated on Jan. 14, 1894.

FOOTNOTES: “150 Years of Faith and Education” and “Claver Society to be renamed Tolton Society,” Saint Ignatius Magazine 11 no. 2 (Summer 2019); “Secured a $500 Collection,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 6, 1893; “St. Monica’s is dedicated,” Chicago Record, Jan. 15, 1894. The True Witness and Catholic Chronicle in 1894 described him as "indefatigable" in his efforts to establish the new parish.[8] Daniel Rudd, who organized the initial National Black Catholic Conference which was held in 1889, was quoted in the November 8, 1888, edition of The Irish Canadian as commenting about the Congress by saying, "For a long time the idea prevailed that the negro was not wanted beyond the altar rail, and for that reason, no doubt, hundreds of young colored men who would otherwise be officiating at the altar rail today have entered other walks. Now that this mistaken idea has been dispelled by the advent of one full-blooded negro priest, the Rev. Augustus Tolton, many more have entered the seminaries in this country and Europe".[9] Another indication of the prominence given Tolton by parts of the American Catholic hierarchy was his participation, a few months later, on the altar at an international celebration of the centenary of the establishment of the first U.S. Catholic diocese in Baltimore. Writing about it in the New York Times edition of November 11, 1889, the correspondent noted that "As Cardinal Gibbons retired to his dais [on the altar at the Mass], the reporters in the improvised press gallery noticed for the first time, not six feet away from him in the sanctuary among the abbots and other special dignitaries, the black face of Father Tolton of Chicago, the first colored Catholic priest ordained in America."[7][10]

Death

Tolton began to be plagued by "spells of illness" in 1893.[1] Because of them, he was forced to take a temporary leave of absence from his duties at St. Monica's Parish in 1895.[6]

At the age of 43, on July 8, 1897,[11] he collapsed and died the following day at Mercy Hospital as a result of the heat wave in Chicago in 1897.[1] After a funeral which included 100 priests,[4] Tolton was buried in the priests' lot in St. Peter's Cemetery in Quincy, which had been his expressed wish.

After Tolton's death, St. Monica's was made a mission of St. Elizabeth's Church. In 1924 it was closed as a national parish, as black Catholics chose to attend parish churches in their own neighborhoods.

Legacy and honors

- Tolton is the subject of the 1973 biography From Slave to Priest by Sister Caroline Hemesath.[1] The book was reissued by Ignatius Press in 2006.

- In 1990, Sister Jamie T. Phelps, O.P., an Adrian Dominican Sister and then-faculty member of the Theology Department at Catholic Theological Union, initiated the Augustus Tolton Pastoral Ministry Program in consultation with Don Senior, President of CTU, the theology faculty, and representatives of the Archdiocese of Chicago, to prepare, educate, and form black Catholic laity for ministerial leadership in the Archdiocese of Chicago.

- The Father Tolton Regional Catholic High School opened in Columbia, Missouri, in 2011.[12]

- Augustus Tolton Catholic Academy opened in the fall of 2015 in Chicago, Illinois. Tolton Academy is the first STREAM school in the Archdiocese of Chicago. A focus on science, technology, religion, engineering, arts, and math sets it apart as a premier elementary school in Chicago. Tolton Academy is located at St. Columbanus Church.

Cause for canonization

On March 2, 2010, Francis George of Chicago announced that he was beginning an official investigation into Tolton's life and virtues with a view to opening the cause for his canonization.[13] This cause for sainthood is also being advanced by the Diocese of Springfield, Illinois, where Tolton first served as priest, as well as the Diocese of Jefferson City, Missouri, where his family was enslaved.

On February 24, 2011, the Roman Catholic Church officially began the formal introduction of the cause for Tolton's sainthood, which must take place in a public session. He is now designated Servant of God Fr. Augustus Tolton. Also at this time there was the establishment of historical and theological commissions, which will investigate the life of Tolton, and the Father Tolton Guild,[14] which is responsible for the promotion of his cause through spiritual and financial endeavors. George assigned Joseph Perry, Auxiliary Bishop of Chicago, to be the Diocesan Postulator for the cause of Tolton's canonization.

On September 29, 2014, George formally closed the investigation into the life and virtues of Tolton. The dossier of research into Tolton's life went to the Vatican, where the documents collected to support his cause will be analyzed, bound into a book called a "positio" or official position paper, and evaluated by theologians, and then, supporters hope, passed on to the pope, who can declare Tolton "venerable" if he determines Tolton led a life of heroic virtue.[15]

On December 10, 2016, Tolton's remains were exhumed and verified as part of the canonization process. Following procedures laid out in canon law, a forensic pathologist verified that the remains (which included a skull, femurs, ribs, vertebrae, pelvis, and portions of arm bones) belong to Tolton. Also found were the corpus from a crucifix, part of a Roman collar, the corpus from Tolton's rosary, and glass shards indicating his coffin had a glass top. After verification, the remains were dressed in a new chasuble and reburied.[16]

On March 8, 2018, historians that consult the Congregation for the Causes of Saints unanimously issued their assent to Tolton's cause after having received and favourably reviewed the positio that was presented to them. On February 5, 2019, the nine-member theological commission unanimously voted to approve the cause. It must now go to the cardinal and bishop members of the Congregation for approval before it is passed to the pope for his final confirmation.[17]

On June 12, 2019, Pope Francis authorized the promulgation of a "Decree of Heroic Virtue", advancing the cause of Servant of God Augustine Tolton. With the promulgation of the decree of heroic virtue, Tolton was granted the title “Venerable”. If the case progresses, the next stage would be beatification, followed by canonization.[18]

See also

- List of slaves

References

- Martha Irvine (January 6, 2007). "Life of first recognized black U.S. priest unknown to most Catholics". The Victoria Advocate. p. E1.

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p439-446

- "Colored Catholics". The Lewsiton (Maine) Daily Sun. December 30, 1893. p. 5.

- "Black Catholics in the U.S." The Afro-American. Baltimore, MD. July 18, 1987. p. 7.

- "Augustine Tolton". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Father Tolton". St. Elizabeth Chicago.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Colored Catholics Meet". The New York Times. January 2, 1889. p. 2.

A national convention of colored Catholics, composed of delegates from nearly all of the colored Catholic churches and societies throughout the country, began its sessions this morning in the St. Augustine Colored Catholic Church in this city [Washington, D.C.]. Every seat in the church was occupied when at 10:30 o'clock Father Talton [sic] of Quincy, Ill., the only colored Catholic priest in the United States, began the celebration of solemn high mass. Immediately in front of and beneath the pulpit sat Cardinal Gibbons, who delivered the sermon."

- "Religious News Items". The True Witness and Catholic Chronicle. February 21, 1894. p. 6.

- "Colored Catholics". The Irish Canadian. Toronto. November 8, 1888. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Cardinals at the Altar". New York Times. November 11, 1889. p. 1. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- "Demise of Father Tolton". The Freeman. Indianapolis, IN. July 17, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Martin, Catherine (November 1, 2011). "Tolton moves classes to new building". Columbia Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "Chicago archdiocese opens canonization cause for first African-American priest". Catholic News Agency. March 3, 2010. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- "The Father Tolton Guild". Father Augustus Tolton Cause for Cannonization. The Archdiocese of Chicago. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Martin, Michelle (September 30, 2014). "Evidence collected for Father Tolton's sainthood cause heads to Vatican". Catholic News Service.

- Duriga, Joyce (December 28, 2016). "Fr. Tolton's remains exhumed, verified; his cause takes step forward". National Catholic Reporter.

- "The Cause for Sainthood of The Servant of God Reverend Augustus Tolton Continues to Advance with the Unanimous Approval of his Virtuous life". Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago. February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- "Pope declares heroic virtue of eight prospective saints - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. June 12, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

Further reading

- Bauer, Roy. "They Called Him Father Gus" (PDF). Diocese of Springfield in Illinois. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

External links

- Fr. Tolton's cause for canonization by the Archdiocese of Chicago

- Fr. Tolton's cause for canonization by the Diocese of Springfield (archived)