Augustus Harris

Sir Augustus Henry Glossop Harris (18 March 1852 – 22 June 1896) was a British actor, impresario, and dramatist, a dominant figure in the West End theatre of the 1880s and 1890s.

Augustus Harris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Augustus Henry Glossop Harris 18 March 1852 Paris, France |

| Died | 22 June 1896 (aged 44) Folkestone, England |

| Occupation | Actor, impresario, dramatist |

| Years active | 1873–1896[1] |

Born into a theatrical family, Harris briefly pursued a commercial career before becoming an actor and subsequently a stage-manager. At the age of 27 he became the lessee of the large Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where he mounted popular melodramas and annual pantomimes on a grand and spectacular scale. The pantomimes featured leading music hall stars such as Dan Leno, Marie Lloyd, Little Tich and Vesta Tilley. The profits from these productions subsidised his opera seasons, equally lavish, starrily cast and with an innovative repertoire. He presented the first British production of Die Meistersinger and the first production anywhere outside Germany of Tristan und Isolde, and revitalised the staging of established classics.

Harris remained in charge at Drury Lane for the rest of his life, and in 1888 took on the additional responsibility of running the Royal Italian Opera House, Covent Garden, modernising its productions and repertory and abandoning the old convention that all operas, whatever their nationality, were sung in Italian. He changed the name of the theatre to The Royal Opera House in 1892. Both at Drury Lane and Covent Garden he engaged the most admired artists, including Hans Richter and Gustav Mahler as conductors, and Emma Albani, Nellie Melba, Adelina Patti, Jean and Édouard de Reszke and Victor Maurel among the singers.

In 1892 Harris took over the failed Royal English Opera House and turned it into a successful music hall with the new name The Palace Theatre of Varieties. He was active in civic affairs, a member of the new London County Council, a sheriff of the City of London and a prominent Freemason. His health gave way under the pressure of his multifarious activities, and after a short illness he died at the age of 44.

Life and career

Early years

Harris came from a musical and theatrical family. His paternal grandfather, Joseph Glossop (1793–1850), was at various times manager of the Royal Coburg Theatre in London (later known as the Old Vic), La Scala, Milan, and the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples;[2] his paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Feron (1797–1853), was a popular soprano, dubbed "The English Catalani";[3] his father, Augustus Glossop Harris (1825–1873), was a leading stage-manager,[n 1] and his mother, Maria Ann, née Bone, was well known as a theatrical costumier under the name of "Madame Alias".[5][6] Augustus senior and his wife had five children all of whom became connected with the theatre.[n 2] Harris was born on 18 March 1852 in the Rue Taitbout, Paris, near the Salle Ventadour, where his father was stage-manager of the Comédie-Italienne opera company.[5][6]

The young Harris was educated in London, and then, from age 12, in Paris at the Lycée Chaptal and the music academy L'École Niedermeyer.[5][10] Friends he made then included the composer Gabriel Fauré, the music publisher Louis Brandus, the opera manager Léon Carvalho, his future brother-in-law Horace Sedger, and the soprano Adelina Patti.[10][11] He completed his education in Hanover to learn German, after which he joined the financial firm Emile Erlanger & Co. and then the Paris house of Tiffany's.[12] After his father died in 1873, Harris abandoned commerce ("I saw no prospect in 'quill driving'")[12] and followed the family's theatrical calling. He made his debut as an actor in the role of Malcolm in Macbeth in September 1873 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester, in a company headed by W. H. Pennington, Geneviève Ward and Tom Swinbourne.[5][13] According to his biographer J. P. Wearing he followed this with juvenile and light comedy roles in Barry Sullivan's company at the Amphitheatre, Liverpool.[1]

The opera impresario J. H. Mapleson engaged Harris as an assistant stage-manager and was soon sufficiently impressed to put him in sole charge of his Italian Opera Company.[1] Harris went on tour with Mapleson's company as stage-manager, together with his younger brother Charles, later best-known as Richard D'Oyly Carte's stage director.[14][n 3] In 1876 Harris was appointed resident stage-manager at the Prince's Theatre, Manchester,[16] and by the end of that year, when he staged the pantomime Sindbad [sic] the Sailor for Charles Wyndham at the Crystal Palace, he had established a high reputation: one reviewer wrote that the management could not possibly have a better stage-manager than Harris.[17]

Moving into management

Harris continued to appear as an actor. In 1877 Wyndham cast him as the juvenile lead in The Pink Dominos at the Criterion Theatre in the West End.[18] It ran for 555 performances, of which Harris did not miss one.[5] He was a competent actor, but his talents and inclination drew him towards management. In 1879, seeing that the huge Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was closed and empty, he determined to reopen it. He had little money but raised enough funds from friends including his future father-in-law to acquire the lease. He was not immediately able to mount a production of his own, and at first he sub-let the theatre to George Rignold, who presented and starred in a spectacular production of Henry V, which lost money, adding to Drury Lane's reputation as an unprofitable house.[5]

Harris followed Rignold's production with the first of his Drury Lane pantomimes, Bluebeard, written by "the Brothers Grinn" (E. L. Blanchard and T. L. Greenwood), lavishly mounted, well-reviewed and financially successful.[5] After a short Shakespeare season, presented by Marie Litton's company, Harris staged the first of his series of melodramas, The World (July 1880), which he co-wrote, staged, and acted in (Wearing comments, "he never took things lightly"). He established a pattern of lucrative melodramas in the late summer and autumn and even more lucrative pantomimes in the winter, all of which subsidised the culturally ambitious seasons he presented in the spring and early summer. In his pantomimes Harris featured top-line music-hall stars – Marie Lloyd, Kate Santley and Vesta Tilley among the women performers and Herbert Campbell, Dan Leno, Arthur Roberts and Little Tich among the men.[5] Some critics held that Harris had vulgarised the pantomime by importing music-hall turns, particularly knockabout comedians, but the theatre historian Phyllis Hartnoll writes that he "had a feeling for the old harlequinade, providing for it lavish scenery and machinery and engaging excellent clowns and acrobats".[19]

In 1881 Harris married Florence Edgcumbe Rendle (1859–1914). They had one child, Florence Nellie (1884–1931), who married the actor Frank Cellier in 1910.[5][20]

Harris's ambitious seasons of high culture included the Meiningen Court Theatre company in 1881, with a repertoire of German plays and Shakespeare in German translations, and the following year Adelaide Ristori and Rignold in Macbeth.[21] In 1882 Harris engaged leading German singers and the conductor Hans Richter for a season of German operas that included the first British performances of Die Meistersinger and the first production anywhere outside Germany of Tristan und Isolde.[5][22] Over the next four years he hosted the Carl Rosa Opera Company's seasons of opera in English, and he also presented operatic seasons sung in the original languages by celebrated international singers. His productions did much to revitalise the presentation of Italian opera in London, which had for some years chiefly consisted of vocal display and little dramatic coherence.[23]

The 1887 opera season at Drury Lane celebrated Queen Victoria's golden jubilee by featuring a particularly starry international cast, including Jean de Reszke, Édouard de Reszke, Victor Maurel, Minnie Hauk and Lilian Nordica. The repertoire was Italian (Il barbiere di Siviglia, La traviata and Rigoletto), French (Les Huguenots, Faust and Carmen) and German or Austrian (Don Giovanni and Lohengrin).[24] Wearing comments that the season was an artistic and social success, but lost £10,000.[5]

As well as the opera, Harris presented serious non-musical drama, including seasons by the Comédie-Française (1893), Eleonora Duse (1895), and the ducal court company of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1895).[5]

Covent Garden

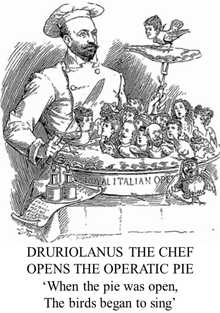

By 1888 Harris was so closely identified with his theatre that he was popularly known as "Druriolanus".[5] He remained in charge at Drury Lane for the rest of his life, but having had to contend with the rival opera seasons of the Royal Italian Opera House, Covent Garden (run by Antonio Lago) and Her Majesty's Theatre (run by Mapleson), he concluded that "in London there is room for but one operatic enterprise at a time", and that he should take over Covent Garden.[25] He assembled a syndicate of influential backers including Lord Charles Beresford, Earl de Grey and Henry Chaplin and took over the lease of the house in early 1888.[26] From May to July he presented a ten-week season with Luigi Mancinelli and Alberto Randegger as conductors and 21 leading singers including Emma Albani, the de Reszkes, Hauk, Nordica, and Nellie Melba in her London debut.[27] The repertoire consisted of 19 operas, beginning with Lucrezia Borgia and ending with Les Huguenots.[n 4]

There was no rival opera season in 1888, but Mapleson mounted an Italian season at Her Majesty's the following year. His mediocre casts, conventional repertoire and old-fashioned productions did not draw the public;[28] by contrast Harris attracted capacity audiences with top-flight stars and works such as Die Meistersinger never before seen at Covent Garden.[29][n 5] He also began a fundamental, and lasting, reform of the house's linguistic policy. In keeping with its title "Royal Italian Opera House", operas of whatever nationality were sung in Italian, including Carmen and Die Zauberflöte ("Il flauto magico").[31] Although 21 of the 22 operas in Harris's 1889 season were sung in Italian, including Die Meistersinger and Les Huguenots, Gounod's Roméo et Juliette was sung in French, an innovation much remarked upon in the press.[32] Harris's decision was widely praised;[32] The Times said:

Harris continued with his policy of starry casts, impressive staging and texts sung in their original language – a practice that became known as "the cosmopolitan system".[34] By 1892, when he engaged Gustav Mahler to conduct the British premiere of The Ring,[n 6] it had become the norm at Covent Garden,[34] and has remained so (with the exception of the late 1940s and 1950s, when opera in English was the general house policy).[36][n 7] To reflect the new reality the "Italian" was dropped from the name of the opera house in the same year.[38] When there was no room in Covent Garden's schedules for a new work that he favoured, he leased another theatre for the purpose.[n 8] At Covent Garden, as earlier at Drury Lane, Harris was keen to present new works; his 1894 season included the world premiere of Massenet's La Navarraise and the British premieres of Massenet's Werther, Puccini's Manon Lescaut and Verdi's Falstaff.[40] He made the auditorium of the Royal Opera House both brighter and darker: he introduced electric lighting in 1892, and instituted the practice of lowering the house lights completely during performances, to the chagrin of those in the expensive seats who were used to directing their attention to their fellow operagoers as much as to the opera.[30]

Palace Theatre of Varieties

Harris played a part in the brief story of Richard D'Oyly Carte's abortive project The Royal English Opera House. Carte commissioned the theatre and opened it in 1891 with Arthur Sullivan's romantic opera Ivanhoe, which ran exceptionally well (161 performances); he followed it with André Messager's The Basoche, for which Harris adapted the original French dialogue into English. Despite enthusiastic reviews The Basoche ran for only 61 performances.[41] Having failed to commission an opera to replace it, Carte eventually sold the theatre, at a loss, to a company formed by Harris to run it as a music hall.[n 9] It re-opened in December 1892, after some remodelling, as The Palace Theatre of Varieties. After running it for a year, Harris appointed the veteran Charles Morton – "the father of the halls"[43] – as manager. Morton, though more than thirty years his senior, continued to run the Palace successfully for eight years after Harris's death.[44]

Last years

In the 1890s Harris maintained his various activities at an unflagging pace. At Covent Garden he presented the debuts of Emma Eames (1891) and Emma Calvé (1892), and visits by Leoncavallo, Mascagni (1893), and Puccini (1894). He took his company to Windsor Castle in 1892, 1893 and 1894 to give Command Performances for Queen Victoria and her family and court.[n 11] In 1895 Harris ("always adept in handling divas" in Wearing's words) persuaded Adelina Patti to return to the stage for a final series of performances.[5]

At Drury Lane, Harris continued to devise elaborate spectacle and effects for his melodramas: in A Life of Pleasure (1893) there was a representation of the promenade at the Empire music hall, and in Cheer Boys, Cheer (1895) the sinking of HMS Birkenhead was spectacularly portrayed.[49] He continued to stage the annual pantomimes, which he wrote in collaboration with Harry Nicholls and others. They ran from Christmas to Easter. An example from the 1890s is Little Bo-Peep, Little Red Riding Hood and Hop o' my Thumb (1892) with Marie Loftus, Marie Lloyd and Little Tich in the title roles, Dan Leno and Herbert Campbell as Mr and Mrs Thumb, and Arthur Williams as the Dame, heading a cast of more than 40. The reviewer in the theatrical paper The Era remarked that every year people felt that Harris had "reached the limit of splendour and ingenuity", and were proved wrong the following year.[50]

In his late thirties Harris began participating in civic affairs, becoming a member of the London County Council in 1890, representing the Strand division.[11] He was appointed a sheriff of the City of London in 1890,[n 12] and was knighted in 1891 in recognition of his contribution to the state visit to Britain of the German Emperor.[5] He was also prominent in Freemasonry, hosting a lodge at Drury Lane, participating in the Savage Club Lodge,[52] and becoming Grand Treasurer of the Grand Lodge of England, under the Prince of Wales as Grand Master.[53]

The reviewer in The Era who praised the 1892 pantomime commented on the astonishing pressures on Harris:

Sir Henry Wood recalled Harris in action:

Harris's health gave way under his enormous workload.[1] In June 1896 he went to the seaside resort of Folkestone for leisure and rest, but developed what at first seemed to be a chill; he was found to be suffering from diabetes.[39][n 13] Over a week his condition deteriorated and he died at the Royal Pavilion Hotel on 22 June 1896 at the age of 44.[39] His funeral, on 27 June at Brompton Cemetery, was attended by several thousand people of all classes ("a final grand procession he would have surely enjoyed", in Wearing's words). Among the mourners were musicians, comedians, managers, authors, singers, critics and politicians, as well as the general public.[55][n 14]

Harris's widow married Edward O'Connor Terry in 1904.[56]

Reputation and memorials

On Harris's death, the critic Clement Scott wrote:

The Illustrated London News said:

In addition to the funerary monument in Brompton Cemetery, Harris is commemorated by a fountain on the Catherine Street side of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. It was designed by Sidney R. J. Smith and erected by public subscription through the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association. Above the fountain is a bronze bust of Harris by Sir Thomas Brock.[59]

Monument in Brompton Cemetery Detail of Brompton monument

Memorial fountain at Drury Lane

Plays

Melodramas

Staged at Drury Lane. Co-authors shown in brackets.

- The World (Paul Meritt and Henry Pettitt) 1880

- Youth (Meritt) 1881

- Pluck: A Story of £50,000 (Pettitt) 1882

- A Sailor and His Lass (Robert Williams Buchanan) 1883

- Freedom (George Fawcett Rowe) 1883

- Human Nature (Pettitt) 1885

- A Run of Luck (Pettitt) 1886

- Pleasure (Meritt) 1887

- The Spanish Armada (Henry Hamilton) 1888

- The Royal Oak (Hamilton) 1889

- A Million of Money (Pettitt) 1890

- The Prodigal Daughter (Pettitt) 1892

- A Life of Pleasure (Pettitt) 1893

- The Derby Winner: A new and original sporting and spectacular drama, (Cecil Raleigh and Hamilton) 1894

- Cheer, Boys, Cheer (Raleigh and Hamilton) 1895

- Source: Dictionary of National Biography.[60]

Pantomimes

After Bluebeard in 1879, Harris's next nine pantomimes at Drury Lane were written by E. L. Blanchard. From 1888 Harris co-wrote them: his collaborators are shown in brackets:

- Babes in the Wood (Blanchard and Harry Nicholls) 1888[61]

- Jack and the Beanstalk or, Harlequin and the Midwinter Night's Dream (Nicholls) 1889[62]

- Beauty and the Beast (William Yardley) 1890[63]

- Humpty Dumpty (Nicholls) 1891[64]

- Little Bo-Peep, Little Red Riding Hood and Hop o' My Thumb (Wilton Jones) 1892[65]

- Robinson Crusoe) (Nicholls) 1893[66]

- Dick Whittington (Raleigh and Hamilton) 1894[67]

- Cinderella (Raleigh and Arthur Sturgess) 1895[68]

Libretti

- The Basoche (1891). Opéra comique in three acts. English dialogue (English lyrics by Eugène Oudin); music by André Messager.[69]

- Amy Robsart (1893). Opera in three acts, based on a story by Walter Scott. Scenario by Harris, developed by Frederic Weatherly in English and Paul Milliet in French; music by Isidore De Lara.[70]

- The Lady of Longford. Opera in one act (1894). Co-written with Weatherly; music by L. Emil Bach.[71]

- The Little Genius (1896). Comic opera in two acts. Adapted from the German (Der Wunderknabe) by Harris and Arthur Sturgess; music by Eugen von Taund, J. M. Glover and Landon Ronald (staged at the Shaftesbury Theatre the month after Harris's death).[72]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- In the 19th century, the term "stage-manager" covered the artistic functions now ascribed to directors as well as the purely technical aspects of staging to which "stage-manager" has subsequently come to be restricted.[4]

- Ellen ("Nelly", Mrs Horace Sedger d. 1897)[7] and Maria (1851–1904) were actresses; Patience, like her mother, was a theatrical costume designer;[8] and Charles (c. 1855–1897), a key member of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company's production team, became known as "the greatest stage-manager of recent years".[9]

- Sir Henry Wood ranked "Charlie Harris" with Hugh Moss, Ernst von Possart and Gordon Craig as the finest stage-managers of his time.[15]

- The others were L'Africaine, Aida, Un ballo in maschera, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Carmen, Don Giovanni, Faust, Guillaume Tell, Lohengrin, Lucia di Lammermoor, The Magic Flute, Mefistofele, Le nozze di Figaro, Rigoletto, La traviata and Il trovatore.[26]

- Harris became known for seeking to outshine any rival opera season: the musicologist Paul Rodmell cites 1891, when Lago presented a programme at the Olympic Theatre that included Lohengrin starring Albani, Harris countered with the same opera starring Melba; he put on a rival production of The Magic Flute in the same season.[30]

- Harris's policy of impressive staging did not, in the opinion of Bernard Shaw, extend to The Ring. Harris imported a German company in a German production that did not impress Shaw: "The scenery is of the usual German type, majestic, but intensely prosaic", with a singularly unconvincing dragon in Siegfried: Shaw said he could improvise a better one "with two old umbrellas, a mackintosh, a clothes-horse, and a couple of towels".[35]

- Rodmell comments that Harris's policy of giving operas in their original language did not extend to British works: he presented several new operas by British composers, but singing in English was not the done thing at Covent Garden in the 19th century and his British novelties were, with a single exception, sung in French or Italian translation.[37]

- Harris took the Opera Comique to premiere Charles Villiers Stanford's Shamus O'Brien (1896).[39]

- Carte lost £32,000; Harris’s company raised £200,000 by a public flotation to enable the deal to be done.[42]

- The full caption continues: Elected Sheriff, June 27, he dreams that he is encountered on his road by the fairy forms of Harry Nicholls and Herbert Campbell. Voices of Fairy Forms: All hail, Druriolanus! Sheriff thou art, and shalt be Mayor hereafter.[45]

- The Command Performances were:

- Carmen, starring Zélie de Lussan and conducted by Enrico Bevignani (1892)[46]

- a double bill of L'amico Fritz and Cavalleria rusticana, starring Emma Calvé and conducted by Pietro Mascagni (1893)[47]

- Faust with Fernando de Lucia as Faust, Pol Plançon as Méphistophélès, Emma Albani as Marguerite and Pauline Joran as Siébel, conducted by Bevignani (1894).[48]

- Sheriff of the City of London was, by the 19th century, a purely ceremonial position. Two sheriffs were elected every year, and like their superior, the Lord Mayor of London, they handed over their posts to newly elected appointees at the end of their year-long term.[51]

- According to Wearing he was also suffering from cancer.[5]

- Among those in the cortège were George Alexander, F. C. Burnand, Herbert Campbell, Richard D'Oyly Carte, Edouard and Jean de Reszke, Dan Leno, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, T. P. O'Connor, Pol Plançon, W. S. Penley, Sir Arthur Sullivan, Edward O'Connor Terry and Herbert Beerbohm Tree.[55]

References

- "Obituary: Sir Augustus Harris", The Times, 23 June 1896, p. 12

- Knight, Joseph and Nilanjana Banerji. "Harris, Augustus Frederick Glossop (Augustus Glossop Harris) (1825–1873), actor and theatre manager", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Cheke, D.J. "Feron, Elizabeth", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press 2002. Retrieved 10 May 2020. (subscription required)

- "stage-manager", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020 (subscription required)

- Wearing, J. P. "Harris, Sir Augustus Henry Glossop (1852–1896), actor and theatre manager", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 10 May 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Mr Augustus Harris", Bow Bells, 28 September 1887, p. 348

- "Theatrical Gossip", The Era, 4 September 1897, p. 12

- Richards, p. 60

- "Death of Mr Charles Harris", The Morning Post, 4 February 1897, p. 5

- "Mr Horace Sedger", The Era, 27 February 1892, p. 11

- "Manager Harris Dead", The New York Times, 23 June 1896

- "Interview with Augustus Harris", The Musical World, 27 September 1884, p. 603

- "Provincial Theatricals", The Era, 5 October 1873, p. 6

- Rosenthal, Harold, and George Biddlecombe. "Harris, Sir Augustus", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 10 May 2020 (subscription required); and Rollins and Witts, pp. 5, 14 and 98

- Wood, p. 85

- "Provincial Theatricals", The Era, 8 October 1876, p. 8

- "Sindbad the Sailor", The Penny Illustrated Paper, 30 December 1876, p. 435

- "Criterion Theatre", The Era, 8 April 1877, p. 5

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, and Peter Found. "Harris, Sir Augustus Henry Glossop", The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford University Press, 2003. Retrieved 11 May. 2020 (subscription required)

- "Obituary: Frank Cellier", The Times, 28 September 1948, p. 7

- "Madame Ristori at Drury Lane", The Times, 5 July, 1882, p. 5

- "Drury Lane", The Times, 8 June 1882, p. 10

- "Opera Under Sir Augustus Harris", The Musical Times, August 1896, p. 521

- "Royal Italian Opera, Drury Lane", The Times, 9 July 1887, p. 13

- "Opera Under Augustus Harris", The Era, 19 February 1898

- "Royal Italian Opera", The Era, 28 July 1888, p. 11

- Parker, pp. 23 and 27

- Parker, p. 32

- Parker, pp. 29 and 31

- Rodmell, p. 59

- "Royal Italian Opera: Il flauto magico", The Era, 30 June 1888, p. 7

- "Royal Italian Opera", The Morning Post, 17 June 1889, p. 2; "Roméo et Juliette", The Saturday Review, 22 June 1889, p. 760; "Current Notes", The Lute: A Monthly Journal of Musical News, July 1889, pp. 65–68; and "Royal Italian Opera", The Era, 22 June 1889, p. 7

- "Royal Italian Opera", The Times, 19 June 1889, p. 13

- Parker, p. 39

- Shaw, pp. 115–116

- Haltrecht, pp. 54–56, 104, 133 and 243; "Covent Garden Reinforced", The Times, 2 July 1960, p. 9; and Heyworth, Peter. "The State of Covent Garden", The Observer, 24 July 1960, p. 25

- Rodmell, p. 55

- Snelson, unnumbered page, "Timeline"

- "Death of Sir Augustus Harris", The Standard, 23 June 1896, p. 5

- Rodmell, p. 56

- Jacobs, Arthur. "Carte, Richard D'Oyly (1844–1901), theatre impresario", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 May 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Goodman, p. 64

- Trussler, p. 229

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 124

- "Excelsior! Or, the Day-Dream of Druriolanus", Punch, 5 July 1890, p. 4

- "Court Circular", The Times, 5 December 1892, p. 6

- "Windsor Castle", The Morning Post, 17 July 1893, p. 5

- "Faust at Windsor Castle", The Illustrated London News, 2 June 1894, p. 675

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 69

- "Drury Lane", The Era, 29 December 1892, p. 8

- "The new sheriffs", The Standard, 29 September 1890, p. 9

- "Savage Club Lodge 2190", Savage Club Lodge. Retrieved 12 May 2020

- "Mr Sheriff Augustus Harris", The Era, 27 September 1890, p. 15

- Wood, p. 86

- "Funeral of Sir Augustus Harris", The Times, 29 June 1896, p. 6

- Taylor, C. M. P. "Terry, Edward O'Connor (1844–1912), actor and theatre proprietor", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Scott, Clement. "The Playhouses", The Illustrated London News, 27 June 1896, p. 803

- "Sir Augustus Harris", The Illustrated London News, 27 June 1896, p. 805

- "Theatre Royal Drury Lane and attached Sir Augustus Harris memorial drinking fountain", Historic England. Retrieved 13 May 2020

- Knight, Joseph. "Harris, Sir Augustus Henry Glossop (1852–1896)") Dictionary of National Biography Macmillan 1901 and Oxford University Press 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- WorldCat OCLC 43253049

- WorldCat OCLC 41379890

- WorldCat OCLC 1124714553

- WorldCat OCLC 1124703439

- WorldCat OCLC 560610138

- WorldCat OCLC 1124707792

- WorldCat OCLC 101331912

- WorldCat OCLC 1124690124

- WorldCat OCLC 222839719

- WorldCat OCLC 751679620

- WorldCat OCLC 751678256

- WorldCat OCLC 21860947

Sources

- Anthony, Barry (2010). The King's Jester. London: Taurus. ISBN 978-1-84885-430-7.

- Goodman, Andrew (1988). Gilbert and Sullivan's London. London: Spellmount. ISBN 978-0-946771-31-8.

- Haltrecht, Montague (1975). The Quiet Showman – Sir David Webster and the Royal Opera House. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-211163-8.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (1963). The Theatres of London. London: Rupert Hart-Davis. OCLC 1110747260.

- Parker, E. D. (1900). Opera under Augustus Harris. London: Saxon. OCLC 21923947.

- Richards, Jeffrey (2005). Sir Henry Irving: A Victorian Actor and his World. London: Hambledon. ISBN 978-1-85285-591-8.

- Rodmell, Paul (2016) [2013]. Opera in the British Isles, 1875–1918. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4094-4162-5.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419.

- Shaw, Bernard (1949) [1931]. Music in London 1890–94, Volume II. London: Constable. OCLC 917750358.

- Snelson, John, ed. (2012). The Royal Opera House Guidebook. London: Oberon. ISBN 978-1-84943-167-5.

- Trussler, Simon (2000). The Cambridge Illustrated History of British Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79430-5.

- Wood, Henry J. (1938). My Life of Music. London: Victor Gollancz. OCLC 30533927.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Augustus Harris. |

- Works by Augustus Harris at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Augustus Harris at Internet Archive

- Augustus Harris on IMDb

- Augustus Harris at the Internet Broadway Database

- Augustus Harris at Find a Grave

- Frederic, Harold (5 July 1896). "Harris was all manager" (PDF). The New York Times.