Olympic Theatre

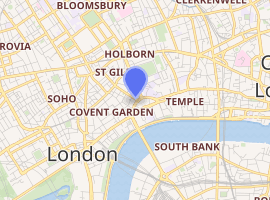

The Olympic Theatre, sometimes known as the Royal Olympic Theatre, was a 19th-century London theatre, opened in 1806 and located at the junction of Drury Lane, Wych Street and Newcastle Street. The theatre specialised in comedies throughout much of its existence. Along with three other Victorian theatres (Opera Comique, Globe and Gaiety),[1] the Olympic was eventually demolished in 1904 to make way for the development of the Aldwych. Newcastle and Wych streets also vanished.

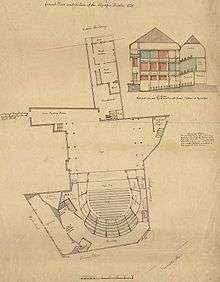

1806 Olympic Pavilion | |

1831 engraving of the Royal Olympic Theatre | |

| |

| Address | Wych Street, Drury Lane Westminster, London |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.513056°N 0.118611°W |

| Designation | Demolished |

| Type | Theatre and opera house |

| Capacity | 889 (1860s) 2,150 (1889) |

| Current use | Site of Kingsway |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1806 |

| Closed | 1899 |

| Rebuilt | 1870 C. J. Phipps 1890 W. G. R. Sprague and Bertie Crewe |

1806-1849: Early days and Madame Vestris

The first Olympic theatre was built in 1806 on the site of Drury House (later Craven House),[2] for the impresario Philip Astley, a retired cavalry officer. The original name of the house was the Olympic Pavilion. It was said to be built from the timbers of the French warship Ville de Paris. It opened on 1 December 1806[3] as 'a house of public exhibition of horsemanship and droll.'[4] In 1813, Astley sold the theatre to Robert William Elliston, who refurbished the interior and renamed it the Little Drury Lane, reflecting its proximity to the large Drury Lane Theatre nearby. Elliston had the theatre substantially rebuilt and reopened it with William Thomas Moncrieff's comedy Rochester – or, King Charles the Second's Merry Days. John Scott purchased the playhouse at Ellison's bankruptcy auction in 1826 and gave the building gas lighting.[3]

In 1830, Lucia Elizabeth Vestris (1787–1856) leased the house,[5] becoming the first female actor-manager in the history of London theatre. She had already made her fortune as a singer, a dancer (of some repute) and an actor. Together with her business partner, Maria Foote, and later with her husband, the actor Charles James Mathews, who joined the company in 1835, Madame Vestris initiated several theatrical innovations, such as the use of historically correct costumes and more elaborate scenery, including a box set with ceiling, which she is said to have introduced in Britain.[4] Her stewardship began with a programme of four pieces including Olympic Revels,[6] and under her management the theatre continued to feature light comedies including music, which were legally styled burlettas and whose licence she had been granted by the Lord Chamberlain.[7] Many were written by J. R. Planché and Charles Dance, featuring Vestris in breeches roles, and the popular comedian of the day, John Liston. The plays often burlesqued classical themes: My Great Aunt – or, Relations and Friends; The Loan of a Lover; The Court Beauties; The Garrick Fever; Faint Heart Never Won Fair Lady; Olympic Revels – or Prometheus and Pandora; Olympic Devils – or Orpheus and Eurydice; The Paphian Bower – or Venus and Adonis; Telemachus – or The Island of Calypso.[8] While Vestris' licence only allowed the performance of extravaganzas and burlesques, the quality of the performance was paramount, with much time spent on rehearsal and selection of the company.[6]

The 1840s were a period of decline for the theatre. Madame Vestris gave her last performance in 1839 and left to join the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden,[6] and the house writers, E. L. Blanchard, John Courtney, Thomas Egerton Wilks, and I. P. Wooler, have not met with posthumous fame.[8]

1850-1889: Comedy, melodrama and operetta

The 1850s were a more successful decade for the theatre. Dion Boucicault's Broken Vow was staged in 1851, Planché began writing for the Olympic again, and John Maddison Morton also wrote many plays for the house. Other playwrights featured at the Olympic in the 1850s were Robert B. Brough, Francis Burnand, John Stirling Coyne, John Oxenford, Mrs Alfred Phillips, John Palgrave Simpson, Tom Taylor, and Montagu Williams.[8] The theatre was managed by the actor-manager Alfred Wigan from 1853 to 1857. The staples of the repertoire in the 1850s and 1860s continued to be comedies, many featuring the great actor and comedian Frederick Robson.[9] A notable exception was Tom Taylor's celebrated 1863 social melodrama, The Ticket-of-Leave Man, based on a French dramatic tale, Le Retour de Melun. It starred Henry Neville, who went on to play in over 2000 performances of the work. Nellie Farren spent two productive years at the theatre early in her career.

In 1863, the theatre closed for extensive alterations and improvements by C. J. Phipps, who was later the architect of the Savoy Theatre (1881), the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue (1888), Her Majesty's Theatre (1897) and many others. The capacity of the theatre was at this time 889. The Olympic reopened with performances of The Girl I Left Behind Me and The Hidden Hand and My Wife's Bonnet in November 1864. Burnand's contributions in the 1860s included Fair Rosamond – The Maze, The Maid, and The Monarch; Deerfoot; Robin Hood – or, The Forrester's Fate!; Cupid and Psyche – or, Beautiful as a Butterfly; Acis and Galatæa – or, The Nimble Nymph and the Terrible Troglodyte! and King of the Merrows – or, The Prince and the Piper. Morton's plays included Ticklish Times; A Husband to Order; A Regular Fix!; and Gotobed Tom!. In 1870, W. S. Gilbert became another of the theatre's notable authors, producing The Princess.[8] Later Gilbert plays at the Olympic were The Ne'er-do-Weel (1878) and Gretchen (1879).

Henry Neville managed the theatre from 1873 to 1879.[10] The 1870s saw the staging of Wilkie Collins's dramatisations of his own novels, The Woman in White and The Moonstone; and Charles Collette in his own one-act musical farce with the striking title, Cryptoconchoidsyphonostomata, or While it's to be Had! (1875),[11] which had opened with Trial by Jury earlier that year at the Royalty Theatre. The Olympic of this period was described by Edward Walford, in his book Old and New London (1897), as having shown 'principally melodramas of the superior kind.' From time to time, operas and operettas were also presented, including Quite an Adventure, and Claude Duval or Love and Larceny by Edward Solomon and Henry Pottinger Stephens,[12] and the rival production of H.M.S. Pinafore mounted in 1879 by Richard D'Oyly Carte's erstwhile partners.[13]

1889-1900: New building and final closure

The building was demolished in 1889 and a new, much enlarged theatre was constructed in 1890 by W. G. R. Sprague and Bertie Crewe, whose surviving theatres in London include the Gielgud, Wyndham's Theatre, the Noël Coward Theatre, the Aldwych Theatre, the Novello Theatre and the Shaftesbury Theatre. The new theatre, with a capacity of 2,150, was large enough to accommodate full-scale opera, including the British première of Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin, conducted by Henry Wood with a cast that included Charles Manners, in 1892.[14]

The last manager of the Olympic was Sir Ben Greet, later manager of the Old Vic. Among his presentations were Hamlet and Macbeth.[15] The film Major Wilson's Last Stand was shown in 1900.[16] The theatre closed permanently in 1900 and was demolished in 1904.[4]

Notes

- Aldwych Theatre history, accessed 23 March 2007.

- 1850 Ordnance Survey map

- Victorian Web site, accessed 23 March 2007.

- City of London, accessed 23 March 2007.

- Pearce, Charles E. Madame Vestris and her times, New York, Brentano's, pp. 161–63

- Theatre Museum (PeoplePlay), accessed 23 March 2007.

- Bratton, Jacky. "Vestris, Lucia Elizabeth (1797–1856)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 12 March 2014 ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1

- Victorian Plays, accessed 23 March 2007.

- Mollie Sands (1979). Robson of the Olympic. The Society for Theatre Research. ISBN 0854300295.

- "The Olympic Theatre: Static Information – list of managers", accessed 21 May 2009

- The Templeman collection, University of Kent, Theatre Collections, accessed 23 March 2007.

- The Musical Theatre Guide, accessed 23 March 2007.

- C20th site, accessed 23 March 2007.

- The Music with Ease, accessed 23 March 2007.

- Emory University's Shakespeare site Archived 10 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 23 March 2007.

- "Theater Royal Timaru". Timaru Herald. New Zealand. LXIV (3220): 1. 26 March 1900.