Atlas Air Flight 3591

Atlas Air Flight 3591 was a scheduled domestic cargo flight operating for Amazon Air between Miami International Airport and George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston. On February 23, 2019, the Boeing 767-375ER(BCF) used for this flight crashed into Trinity Bay during approach into Houston, killing the two crew members and one passenger on board. The accident occurred near Anahuac, Texas, east of Houston, shortly before 12:45 CST (18:45 UTC).[2][3][4] Debris was found in the shallow waters of Trinity Bay, ranging from small articles of clothing to large aircraft parts. This was the first fatal crash of a Boeing 767 freighter.[5]

.jpg) N1217A, the Boeing 767 involved, seen nine days before the accident | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | February 23, 2019 |

| Summary | Crashed during approach due to pilot error |

| Site | Trinity Bay; near Anahuac, Texas 29°45′50″N 94°42′53″W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 767-375(ER)(BCF) |

| Aircraft name | CustomAir Obsession[1] |

| Operator | Atlas Air (for Amazon Air) |

| IATA flight No. | 5Y3591 |

| ICAO flight No. | GTI3591 |

| Call sign | Giant 3591 |

| Registration | N1217A |

| Flight origin | Miami International Airport, Miami, Florida, United States |

| Destination | George Bush Intercontinental Airport, Houston, Texas, United States |

| Occupants | 3 |

| Passengers | 1 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Fatalities | 3 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Accident

Atlas Air 3591 was on approach towards Houston when it made a sharp turn south before going into a rapid descent. Witnesses to the crash described the plane entering a nosedive; some also recalled hearing "what sounded like lightning" before the Boeing 767 hit the ground.[6][7]

At 12:36 CST (18:36 UTC) radar and radio contact was lost. There was no distress call.[8] Shortly before 12:45 CST (18:45 UTC), Flight 3591 crashed into the north end of Trinity Bay at Jack's Pocket.[3] The area of water is within Chambers County, Texas, and is in proximity to Anahuac.[9]

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued an alert after radar and radio contact was lost around 30 miles (50 km) southeast of its destination.[10] Air traffic controllers tried at least twice to contact the flight, with no response. Controllers asked pilots aboard two nearby flights if they saw a crash site, both of whom said they did not.[11]

The United States Coast Guard dispatched a helicopter and several boats to search for survivors. Numerous other agencies responded as well. The largest piece of aircraft debris found was less than 50 ft (15 m) in length. Some of the debris had the Amazon logo visible. The accident site was only accessible via airboat and helicopter.

The water varies in depth from zero to five feet (1.5 m) deep and is partially mud marsh.[12]

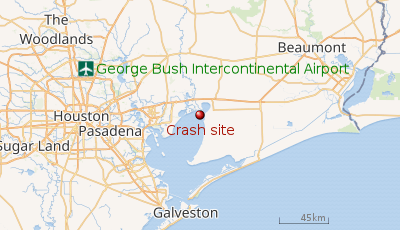

|

| Map of Crash Site |

Aircraft

The Boeing 767-375ER (MSN 25865/430) aircraft was registered N1217A and was nearly 27 years old at the time of the accident, having been built in 1992. It was originally ordered by Canadian Airlines, but first placed into service by China Southern Airlines through GPA, an aircraft leasing company.[13] In 1997, it was transferred to LAN Airlines and flew for 19 years before being stored in January 2016. It was converted into a freighter in April 2017, and placed into service for Amazon Prime Air by Atlas Air.[14] In August 2018, Amazon named two aircraft in its fleet, including N1217A as CustomAir Obsession. The name, painted on the aircraft just aft of the cockpit windows,[15] was a near homonym of "customer obsession," an Amazon leadership principle.[16] The aircraft had accumulated more than 91,000 hours over 23,300 flights[17][18][19] and was powered by two GE CF6-80 turbofan engines.[20]

Victims

There were three people onboard the aircraft.[21] On February 24, Atlas Air confirmed that all three died.[4][22]

Captain Ricky Blakely of Indiana (60), First Officer Conrad Jules Aska of Antigua (44), and Mesa Airlines Captain Sean Archuleta of Houston (36; a jumpseater aboard the flight) were first identified as the three victims on social media by friends and family. Sean Archuleta was in his final week of employment at Mesa Airlines, and was traveling home before beginning new-hire pilot training with United Airlines, scheduled for the following week.[23] By February 26 the bodies of all three had been recovered, and by March 4 all had been positively identified.[24]

Captain Blakely had logged a total of 11,172 flight hours, including 1,252 hours on the Boeing 767. First officer Aska had logged 5,073 flight hours with 520 of them on the Boeing 767.[25]

Investigation

.jpg)

.jpg)

Investigators from the FAA, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) were dispatched to the accident site with the NTSB leading the accident investigation.[26] A dive team from the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) was tasked with locating the aircraft's flight recorders and dive teams from the Houston and Baytown police departments were also on-scene assisting in the search.[27] The cockpit voice recorder and flight data recorder were located and transported to an NTSB lab for analysis.[28][29] It was thought that crews would likely remain at the accident site for weeks for recovery.[30]

As of March 2019, the cause of the accident had not been determined.[31] It was noted that storm cells were nearby at the time of the accident, but this is not unusual for Bush Intercontinental.[32] CCTV cameras at the Chambers County jail show the airplane in a steep, nose-low descent just prior to impact.[33][34]

The FAA, Boeing, Atlas Air, National Air Traffic Controllers Association (NATCA), International Brotherhood of Teamsters (the pilots' labor union), Air Line Pilots Association,[35] and engine maker General Electric assisted or offered their assistance to the NTSB inquiry.[36]

After listening to the cockpit voice recorder the NTSB stated that "Crew communications consistent with a loss of control of the aircraft began approximately 18 seconds prior to the end of the recording."[31] On March 12 the NTSB stated that the airplane "pitched nose down over the next 18 seconds to about 49° in response to column input." Later that same day the statement was changed to "...in response to nose-down elevator deflection."[18][37]

On December 19, 2019, the NTSB released a public docket containing over 3,000 pages of factual information it had collected during the investigation, with a final report to follow at an unspecified later date. The docket contains information on "operations, survival factors, human performance, air traffic control, aircraft performance, and includes the cockpit voice recorder transcript, sound spectrum study, and the flight data recorder information."[38]

On June 11, 2020, the NTSB announced that the next board meeting would determine the cause of the accident;[39] the NTSB determined during a public board meeting held on July 14, that the flight crashed because of the first officer’s inappropriate response to an inadvertent activation of the airplane's go-around mode, resulting in his spatial disorientation that led him to place the airplane in a steep descent from which the crew did not recover.[40] The NTSB released an animation of the mishap sequence of events from the selection of Go-Around thrust to the fatal crash 31 seconds later.[41]

On August 6, 2020, the NTSB released the final accident report, which stated:

"The NTSB determines that the probable cause of this accident was the inappropriate response by the first officer as the pilot flying to an inadvertent activation of the go-around mode, which led to his spatial disorientation and nose-down control inputs that placed the airplane in a steep descent from which the crew did not recover. Contributing to the accident was the captain’s failure to adequately monitor the airplane’s flightpath and assume positive control of the airplane to effectively intervene. Also contributing were systemic deficiencies in the aviation industry’s selection and performance measurement practices, which failed to address the first officer’s aptitude-related deficiencies and maladaptive stress response. Also contributing to the accident was the Federal Aviation Administration’s failure to implement the pilot records database in a sufficiently robust and timely manner."[42]

Lawsuits

On May 20, 2019, the estate of Captain Sean Archuleta filed a suit against Amazon and Atlas Air in federal court. The suit accuses the defendants of failing to operate the aircraft in a safe manner.[43]

On September 9, 2019, the family of first officer Conrad Jules Aska filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Amazon and Atlas Air, citing improper training and negligence.[44]

See also

References

![]()

- "Taking flight". aboutamazon.com. August 21, 2018.

- "Cargo jet with three reported aboard crashes in water near Houston". NBC News.

- Josephs, Leslie (February 23, 2019). "Atlas Air Flight 3591: Cargo jet crashes near Houston with 3 aboard". cnbc.com.

- "Atlas Air Confirms Family Assistance Established in Flight 3591 Accident". Atlas Air Worldwide. February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 767-375ER (BCF) (WL) N1217A Trinity Bay, near Anahuac, TX". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- Kennedy, Megan; Taylor, Brittany; Aufdenspring, Matt (February 23, 2019). "3 presumed dead after cargo jet nose-dived into Trinity Bay, sheriff says". KPRC.

- Wrigley, Deborah (February 24, 2019). "Witnesses recall moments before Atlas Air cargo plane crash in Chambers Co". ABC13 Houston. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- "One victim identified in deadly cargo jet crash in Chambers County". abc13.com. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "Human remains found after Atlas Air cargo plane crashes in Chambers Co". KTRK-TV. February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Law, Tara. "Cargo Boeing 767 Plane, Carrying 3, Crashes Into Texas Bay". Time. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- Warren, David; Bleiberg, Jake (February 24, 2019). "Sheriff: No likely survivors in jetliner crash near Houston". Associated Press. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "Human remains found cargo plane crash in Chambers Co". ABC13 Houston. February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "Amazon Cargo Aircraft Crashes on Flight 3591". aviationcv.com. February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Mollenhauer, Alec (October 21, 2017). "Tracking Amazon Prime Air's fleet: aircraft from six continents and 35 airlines". aeronauticsonline.com. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- Sales, Luis (November 22, 2018). "Optimus' cousin, N1217A, CustomAir Obsession". Retrieved February 26, 2019 – via Facebook.

- "Leadership Principles". amazon.jobs. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- "[UPDATE 8] Atlas Air Boeing 767 Operating for Amazon Prime Air Crashes". Aviation Tribune. February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- "Atlas Air #3591 crashed into Trinity Bay DCA19MA086". www.ntsb.gov. National Transportation Safety Board. DCA19MA086. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Accident Preliminary Report Accident Number: DCA19MA086". National Transportation Safety Board. July 29, 2019. DCA19MA086. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "FAA Registry, N1217A". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Collman, Ashley. "Breaking news: Boeing 767 cargo plane crashes in Texas, reportedly killing all three on board". INSIDER.

- Hughes, Trevor. "Three confirmed dead after Amazon Prime Air cargo plane crash in Texas". USA Today. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Schuetz, R. A. (February 24, 2019). "3 confirmed dead after Boeing 767 cargo plane's nose dive into Trinity Bay". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- Jordan, Jay R. (March 4, 2019). "Pilot's remains positively identified in deadly Atlas Air cargo plane crash". CBS News. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- "Operations Group Chairman's Factual Report" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. November 19, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- Almasy, Steve; Silverman, Hollie. "Cargo jet with 3 aboard crashes in Texas". CNN.

- "Two bodies recovered after a cargo plane crashes in water near Houston". CNN. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Black box recovered at Amazon plane crash site in Anahuac". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- Vera, Amir (March 3, 2019). "NTSB recovers flight data recorder from cargo plane crash near Houston". CNN. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "Sheriff: No likely survivors in jetliner crash near Houston". WHEC News10NBC. February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "NTSB Laboratory Completes Initial Review of Cockpit Voice Recorder, Recovers Flight Data Recorder". www.ntsb.gov. National Transportation Safety Board. March 5, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Scherer, Jasper; Despart, Zach (February 23, 2019). "Sheriff: 'I don't believe anyone could survive' cargo plane's nose dive into Trinity Bay". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- Josephs, Leslie (February 24, 2019). "Atlas Air Flight 3591: NTSB starts investigation into cargo jet crash". CNBC.

- "Air disaster Boeing 767-375ER crash in Trinity Bay, near Anahuac, USA". YouTube. February 27, 2019.

- "ALPA Statement on Atlas Air Flight 3591 Accident". ALPA. Air Line Pilots Association. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- Hemmerdinger, Jon. "Video shows Atlas 767F in 'steep' dive prior to crash: NTSB". FlightGlobal.com. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "NTSB update on Atlas Air B767 crash: nose pitched down to about 49° 'in response to elevator deflection'". ASN News. Aviation Safety Network. March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "NTSB Opens Public Docket for Investigation of Atlas Air Flight 3591 Cargo Plane Crash". www.ntsb.gov. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- "MEDIA ADVISORY: Fatal Atlas Air Flight 3591 Cargo Plane Crash Subject of Board Meeting". www.ntsb.gov. National Transportation Safety Board. June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "First Officer, Captain Actions, Aviation Industry Practices, Led to Fatal Atlas Air Crash". NTSB. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "NTSB Animation - Rapid Descent and Crash into Water Atlas Air Inc. Flight 3591". Youtube. National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Rapid Descent and Crash into Water, Atlas Air Inc. Flight 3591, Boeing 767-375BCF, N1217A, Trinity Bay, Texas, February 23, 2019" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. July 14, 2020. NTSB/AAR-20/02. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- Yates, David. "Amazon, Atlas Air sued for fatal aircraft crash in Trinity Bay". SE Texas Record. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- Premack, Rachel. "The family of a pilot who died in this year's Amazon Air fatal crash is suing Amazon and cargo contractors claiming poor safety standards". Business Insider. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to N1217A (aircraft). |

National Transportation Safety Board

- Air Traffic Control recording

- Air Traffic Control recording transcript

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript

- CVR sound spectrum study

- Flight Data Recorder readout

- NTSB Animation of Flight 3591 Accident on YouTube

- NTSB Board Meeting on Accident on YouTube

Other media