Houston Police Department

The Houston Police Department (HPD) is the primary law enforcement agency serving the City of Houston, Texas, United States and some surrounding areas. With approximately 5,300 officers and 1,200 civilian support personnel it is the fifth-largest municipal police department, serving the fourth-largest city in the United States. Its headquarters are at 1200 Travis in Downtown Houston.

| Houston Police Department | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | HPD |

| Motto | Order through law, justice with mercy |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1841 |

| Employees | 6,258 (2020) |

| Annual budget | $965 million (2021)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Houston, Texas, USA |

| |

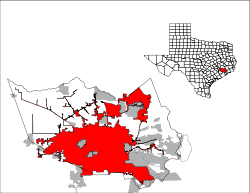

| Map of Houston Police Department's jurisdiction. | |

| Size | 601.7 square miles (1,560 km2) |

| Population | 2,326,090 (2018) |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | 1200 Travis Downtown Houston |

| Police officers | 5,229 (2020)[1] |

| Unsworn members | 1,029 |

| Elected officer responsible |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Facilities | |

| Helicopters | 16 (5 on patrol) |

| Website | |

| houstonpolice.org | |

HPD's jurisdiction often overlaps with several other law enforcement agencies, among them the Harris County Sheriff's Office and the Harris County Constable Precincts. HPD is the largest municipal police department in Texas.

According to the HPD's website, "The mission of the Houston Police Department is to enhance the quality of life in the City of Houston by working cooperatively with the public and within the framework of the U.S. Constitution to enforce the laws, preserve the peace, reduce fear and provide for a safe environment."[2]

As of 2020, the chief of police is Hubert Arturo "Art" Acevedo.[3][4]

History

Beginnings

.jpg)

Houston was founded by brothers Augustus and John Kirby Allen in 1836 and incorporated as a city the next year, 1837. As the city quickly grew, so did the need for a cohesive law enforcement agency. The Houston Police Department was founded in 1841. The first HPD badge issued bore the number "1."

The early part of the 20th century was a time of enormous growth for both Houston and for the Houston Police Department. Due to growing traffic concerns in downtown Houston, the HPD purchased its first automobile in 1910 and created its first traffic squad during that same year. Eleven years later, in 1921, the HPD installed the city's first traffic light. This traffic light was manually operated until 1927, when automatic traffic lights were installed.

As Houston became a larger metropolis throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the HPD found itself growing and acquiring more technology to keep up with the city's fast pace. The first homicide division was established in 1930. During that same year, the HPD purchased newer weapons to arm their officers: standard issue .44 caliber revolvers and two Thompson submachine guns. In 1939, the department proudly presented its first police academy class. The Houston Police Officers Association (HPOA) was created in 1945. This organization later became the Houston Police Officers Union.[5] The first African American woman police officer on the force, Margie Duty, joined the HPD in 1953, starting in the Juvenile Division.[6]

Throughout the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, the HPD also experienced its own highs and lows. The HPD bomb squad was created in 1965. Informally, it is known to have existed since 1956 as Sgt. 'Army' Armstrong, was a one-man Bomb Squad, responding to any explosive related event. The next year, 1967, saw massive riots at Texas Southern University. During the riots, one officer was killed and nearly 500 students were arrested. It was as a result of these riots that the still-active Community Relations Division was created within the HPD. In 1970, the Helicopter Patrol Division was created with three leased helicopters. That year also marked the department's first purchase of bulletproof vests for their officers. The HPD's first Special Weapons and Tactical Squad (SWAT) was formed in 1975.

Modern times

In 1982, the Houston Police Department appointed its first African-American chief of police, Lee P. Brown, who succeeded B.K.Johnson. Brown served as chief from 1982 to 1990 and later became the City of Houston's first African-American mayor in 1998. While Brown was considered a successful chief, he also earned the unflattering moniker "Out of Town Brown" for his many lengthy trips away from Houston during his tenure.[7]

Brown's appointment was controversial from the start. Traditional HPD officers frowned upon Brown because he was an outsider from Atlanta, Georgia where he was the police commissioner; to become the police chief in Houston, an officer has to advance through the rank and file although the "good old boy" culture was prevalent.

The HPD paved a new road again in 1990 when Mayor Kathy Whitmire appointed Elizabeth Watson as the first female chief of police. Elizabeth Watson served from 1990 to 1992 and was followed by Sam Nuchia, who served as police chief from 1992 to 1997. In 1997, Clarence O. Bradford was appointed as chief. In 2002, Bradford was indicted and later acquitted of perjury charges, stemming from an incident in which he allegedly lied under oath about cursing fellow officers.[8] Since late 2007, Bradford was the Democratic nominee for Harris County District Attorney where he will be facing a Republican opponent (either Kelly Siegler or Patricia Lykos; the incumbent, Charles A. 'Chuck' Rosenthal, resigned prior to withdrawing his candidacy due to an e-mail scandal). Bradford faced Patricia Lykos and lost the election; he later campaigned in 2009 for a Houston City Council at-large council seat vacated by Ronald C. Green, who ran for controller. Bradford's city council seat tenure as of 2015 is term limited under the City of Houston charter where he was listed as a viable candidate for Mayor of the City of Houston since the incumbent, Annise Parker, was in her final term. In 2016, Sylvester Turner was elected Houston's mayor after defeating Adrian Garcia, former Houston Police Officer and Harris County Sheriff, and others. It was Garcia, a relatively late entry into the race, who missed out on potential endorsements from multiple police agency officer's unions and associations in Harris County that had already endorsed Turner before Garcia, who was by most accounts a popular and well-respected County Sheriff and community leader, entered the race. (Garcia later campaigned for TX Congressional District 29 in the Democrat primary and lost to incumbent Gene Green; Garcia's successor on the Houston City Council, Ed Gonzalez, did campaign for Harris County Sheriff and won in the 2016 election season defeating Ron Hickman, who was appointed by Harris County Commissioners Court to serve out Garcia's unexpired term.) Likely, many of these police agency associations, as well as other major endorsers, such as The Houston Chronicle, who had already declared their support for Turner, would have likely backed Adrian Garcia. This, as much as anything else, probably cost Garcia the election. Sylvester Turner became Mayor of Houston in January 2016.

Under Mayor Turner, Houston Police Department has seen a mass exodus of officers, due in large part to ongoing conflict between the Mayor's office and the Houston Police Department's Pension Fund Management. In early 2017, changes were made to the police officers pension fund, which resulted in many long-serving officers to lose part of their contributions, which are being funneled back into the aggregate fund in order to bolster the fund's holdings. Multiple controversies over this and other issues related to the pension, retirement rank and calculations of pension amounts have resulted in a substantial number of police officers retiring from HPD before the new pension policies went into effect. A substantial number of officers are continuing to retire or resign, causing the number of police officers who are actually and actively working in some capacity as licensed peace officers to be in drastic decline. Among those divisions hardest hit includes the Patrol Divisions. While Houston Police Department spokespersons repeatedly declined to provide solid or specific numbers of patrol officers actively "working the streets," current officers in multiple areas (Patrol Districts) frequently complain about a lack of manpower, inadequate and slow-to-respond back-up units, and citizens join these officers in reporting increasingly poor response times and inadequate police presence on active scenes. These officers worry about increased safety concerns and fears related to greater danger to the officers because of the lack of manpower, especially during the night shift. Sometimes, officers working the overnight shift must contend with only one or two units covering an entire "beat," areas which are subdivisions of Districts. It is now routine, for example, for officers covering a beat to have units who are assigned two or three beats away called away from their beats to respond to calls for assistance or extra manpower. This not only impacts response time to a fellow officer who is calling for urgent help, but it then leaves other beats with reduced and often no coverage for their own beats while they are responding to an officer in another beat. These situations are now commonplace in many Police Districts. A recent estimate given by a high-ranking supervisor for HPD was that there are approximately 3,500 sworn officers (the total umber of actively employed, licensed peace officers in all Divisions and administrative positions) currently serving as Houston Police Officers. By comparison, this is roughly equal to the number of sworn HPD officers employed 25 – 30 years ago. While the Mayor's Office and newly appointed Houston Police Chief Arturo "Art" Acevedo's (Formerly Chief of Police for Austin, Texas) Office maintain that they are "filling the gaps," at the current rate of attrition (officers leaving HPD via retirement and resignation) compared to the number of new officers graduating from the HPD Academy (the "classroom" portion of which lasts approximately six months and the "practical" portion of which lasts another six months), even with multiple classes overlapping (approximately 4 classes of 50 cadets each) it will take more than a decade, using the most "optimistic" projections, just to return The Houston Police Department to the often-promoted number of 5,000 police officers. When one is reminded of that other often-quoted statistic that Houston is the "fastest growing city in the nation" (actually, recent reports from the US Census Bureau show Houston dropping to number two last year, thanks in large part to the current oil bust[9]) and that as the fourth largest city in the United States (provided that Houston has not already overtaken Chicago's population, which by some estimates it has), simply bringing Houston's police force back to 5,000 officers after 10 more years of substantial growth (Houston added an estimated 85,000+ individuals during 2016), Houston could potentially add 1 to 1.5 million people during the next decade of growth. By comparison, the Chicago Police Department has approximately 12,000+ sworn officers.[10] These numbers are similar on both their Wikipedia page as well as the Chicago Police Department's website. So in comparison between these two cities with virtually identical populations, Chicago has four times the number of police officers and shows a negative growth trend (their population is declining over the last several years) while Houston, with 3,000 sworn officers, has the number two growth trend of any city in the nation.

Since 1992, the Houston City Marshal's division, Houston Airport Police, and Houston Park Police were absorbed into HPD. In early 2004, during Mayor Bill White's first term in office, HPD absorbed the Neighborhood Protection division from the City of Houston Planning Department, which was renamed the Neighborhood Protection Corps in 2005. Annise Parker, Mayor White's successor, moved the Neighborhood Protection Corps into the Department of Neighborhoods when the new city division was established in August 2011 - the NPC was renamed as the Inspections and Public Service division of the Department of Neighborhoods.

Crime laboratory

In November 2002, the CBS local TV station KHOU began broadcasting a multi-part investigation into the accuracy of the HPD Crime Lab's findings. Particularly of interest to the reporters were criminal cases that involved DNA analysis and serological (body fluid) testing. Night after night journalists David Raziq, Anna Werner and Chris Henao presented case after case in which the lab's work was dangerously sloppy or just plain wrong and may have been sending the innocent to prison while letting the guilty go free. As a result of those broadcasts, at the end of the week the Houston Police Department declared they would have a team of independent scientists audit the lab and its procedures. However, the audit's findings were so troublesome that one month later, in mid- December, HPD closed the DNA section of the laboratory. Not only did the audit bolster KHOU's report but also found that samples were contaminated and the lab's files were very poorly maintained. The audit revealed that a section of the lab's roof was leaking into sample-containment areas, lab technicians were seriously undereducated or unqualified for their jobs, samples had been incorrectly tagged, and samples had been contaminated through improper handling. Worse, many people had been convicted and sent to prison based upon the evidence contained in the crime lab. The New York Times asked the question, "Worst Crime Lab in the Country?" in a March 2003 article.[11]

Beginning in early 2003, the HPD Crime Lab began cooperating with outside DNA testing facilities to review criminal cases involving cases or convictions associated with Crime Lab evidence. However this again came as a result of some prompting investigatory work done by the TV station KHOU. Not long after their first broadcasts, reporters David Raziq, Anna Werner and Chris Henao got an e-mail from a local mother. She was desperate. She told them that her son, Josiah Sutton, had been tried for rape in 1999 and found guilty based upon HPD Crime Lab testing. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. So KHOU began to take an intensive look at the Sutton case. Raziq and Werner analyzed the HPD lab's DNA report with the help of DNA expert Bill Thompson of the University of California-Irvine. They found terrible and obvious mistakes in the report that the lab should have known about. When the reporters presented this new information to the local jurists who had helped convict Sutton, they were mortified. Not long after that broadcast, the HPD agreed to an immediate retest of the DNA evidence in the Sutton case. Those tests showed the DNA collected in the case did not belong to Sutton. He was released from prison in March 2003 and given a full pardon in 2004.

As a result of the scandal, nine Crime Lab technicians were disciplined with suspensions and one analyst was terminated. However, that analyst was fully reinstated to her previous position in January 2004, less than one month after her December 2003 termination. Many HPD supervisors and Houston residents called for more stringent disciplinary actions against the Crime Lab employees. However, the city panel responsible for disciplining the lab technicians repeatedly resisted these arguments and instead reduced the employees' punishments . Irma Rios was hired in 2003 as Lab Director, replacing Interim Lab Director Frank Fitzpatrick.

In May 2005, the Houston Police Department announced that with much effort and coordination on their part, they had received national accreditation through the American Society of Crime Lab Directors (ASCLD). The ASCLD stated that the lab had met or exceeded standards for accreditation in all areas except DNA.[12] Through independent research and testing, it was determined in January 2006 that of 1,100 samples reviewed, 40% of DNA samples and 23% of blood evidence samples had serious problems.[13] On June 11, 2007, the HPD crime lab reported its DNA section had gained full accreditation from ASCLD.[12]

In the October 6, 2007 The Houston Chronicle published allegations of Employees cheating on an open-book proficiency test.[14]

Safe Clear

The Safe Clear program was implemented by Mayor Bill White on January 1, 2005 as a joint venture between the City of Houston and the Houston Police Department.[15] The intention of the program was to decrease the freeway accidents and traffic jams that occurred due to stalled drivers. Select tow truck companies across the city were authorized to tow a stalled vehicle as soon as possible after being notified by an HPD officer. Persons having their vehicle towed were provided with a Motorist's Bill of Rights and were required to pay a sum to the City of Houston after the towing had taken place.

The program was initially very unpopular among Houston residents. Frequent complaints were that the program unfairly punished lower-income motorists by enforcing a high towing fee and that the program could potentially damage vehicles that required special tow trucks and equipment to be safely towed away. Other complaints were that stranded motorists did not have an option to choose their own garage. The city and the HPD addressed these concerns with program improvements that provided funds to pay for short tows that removed stalled vehicles from the freeway and then allowed drivers to choose their own garage and tow companies once they were safely off the freeway.[16]

Studies released in February 2006 indicate that Safe Clear has been successful during its fledgling year. There were 1,533 fewer freeway accidents in 2005, a decrease of 10.4% since Safe Clear's implementation.[17]

Red light cameras

In December 2004, Chief Hurtt (when he was the former chief of Oxnard, CA) stated that when the city of Oxnard installed their red light cameras, it has claimed that red light running decreased dramatically although Houston was in the process of favoring red light camera enforcement.[18] The history of red light camera enforcement goes back to the 78th Texas Legislature where this measure was voted down although a transportation bill authored by a member of the Texas House of Representatives had an inclusion of red light camera enforcement. In December 2004, the Houston City Council unanimously voted for red light camera enforcement although Texas State Representative Gary Elkins (R-TX) introduced legislation to deter Houston from amending its city charter for the red light camera rule to be enforced. This measure failed in the Texas Senate although in 2005, four intersections in downtown Houston were used as testbeds for red light camera equipment. After a contract was approved, the enforcement went online September 1, 2006 to which those running a red light (there are 50 locations[19]) are fined a $75 civil fine as opposed to a $225 moving violation which goes against the vehicle operator.[20]

There are fifty intersections with red light cameras in the city with cameras (twenty intersections were added where dual cameras were installed). A majority of them are located at a thoroughfare at a freeway intersection - primarily in the Galleria and southwest Houston. During a Houston City Council meeting on 6.11.08, council member James Rodriguez suggested the installation of an additional 200 cameras.[20]

A voter referendum during the 2010 Texas gubernatorial elections to eliminate red-light cameras passed. The referendum that passed in November 2010 was later invalidated by U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes June 17, 2011 citing that the referendum violated the city charter despite the contract with American Traffic Solutions, which provided the camera equipment. The cameras were expected to be reactivated after midnight on July 24, 2011; plans were underway to have this judicial ruling heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.[21][22]

Mobility Response Team

On July 2, 2007, Mayor Bill White started a new program called the "Mobility Response Team". Staffed by traffic enforcement officers patrol within the loop clearing traffic problems. They report traffic light outages, issue parking citations, help clear and direct traffic around minor accidents, or traffic jams during special events in the area. The duties will only involve surface streets and not the freeways and will be using scooters and police cruisers fitted with yellow flashing lights rather than the typical red and blue lights.

This was part of the mayor's plan to improve mobility in city and is the first of its kind in the United States. The city's mobility response team cost $1.8 million a year to operate.[23]

Overtime and "Hot Spot" patrol concentration

Hurtt spent around $24 million on overtime pay through 2010. That money would continue to bolster an understaffed force as police commanders try to increase their ranks.[24] The overtime that is planned would be about equal to 500,000 police hours of which would help bolster various departments including, vice, Westside patrol and traffic enforcement, among other areas including a new 60-member crime reduction unit that will serve as a citywide tactical squad.[24]

The police chief said the effort will put more officers to work immediately in troubled areas of the city such as Third Ward and Acres Homes, where the bodies of seven women have been found in the past two years.[25]

The crime rate, particularly for violent offenses, since the latter part of 2005, when an influx of hurricane evacuees increased the city's population by more than 100,000, and incidents spiked in certain neighborhoods.[26]

Use of violence by the police

In 2013 Jo DePrang of the Texas Observer wrote that "According to citizens, community activists, a veteran Houston police officer and even the president of the local police union, the scenario of multiple officers beating an unarmed suspect happens nearly every day."[27] From circa 2007-2013 there were 588 times observers reported what they deemed inappropriate "use of force", and the internal affairs division dismissed 584 of them, with the other four being pursued.[27]

Pecan Park raid

Helicopter crash

In the morning of May 2, 2020, HPD's helicopter crashed in an apartment complex in north Houston, killing officer Jason Knox and injuring another. [28]

Organization

The Houston Police Department is headed by a chief of police appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the city council. This position is aided by two executive assistant chiefs, ten assistant chiefs, 44 captains, approximately 220 lieutenants and 900 sergeants. HPD headquarters, 1200 Travis, is in Downtown Houston. The current Chief of Police is Hubert "Art" Acevedo.

HPD divides the city into 13 patrol divisions. Each division is divided into one or more districts and each district is divided further into one or more beats. Stations are operated and staffed 24 hours a day. HPD also operates 29 store front locations throughout the city. These store fronts are not staffed 24 hours a day, and generally open at either 7:00 or 8:00 AM, and close at 5:00 PM. Downtown Houston is patrolled by the Downtown Division, and the Houston Airport System facilities have their own divisions.[29]

A map of all stations and store front locations can be found at the HPD web site.[29]

Organizational chart

[30] Office of the Chief of Police

- Office of Public Affairs

- Office of Legal Services

- Office of Budget & Finance

- Professional Standards Command

- Inspections Division

- Internal Affairs Division/Central Intake Office

- Crime Analysis and Command Center Division

- Office of Planning

- Strategic Operations

- Homeland Security Command

- Night Command/Security Operations

- Air Support Division

- Airport Division - IAH (District 21 - George Bush Intercontinental Airport)

- Airport Division - Hobby (District 23 - William P. Hobby Airport and Ellington Field)

- Criminal Intelligence Division

- Special Operations Division (based in the northeast section of the George R. Brown Convention Center)

- Mounted Patrol Detail

- Special Response Group

- Bicycle Administration and Training Unit

- Tactical Operations Division

- SWAT Detail

- Dive Team

- Patrol Canine "Doggie" Detail

- Marine Unit

- Bomb Squad

- Hostage Negotiation Team

- Professional Development Command

- Psychological Services

- Training Division

- Administration

- Certification

- Cadet Training

- Field Training Administration Office

- In-Service Training

- Firearms Training/Qualification Range

- Defensive Tactics

- Drivers Training

- Employee Services Division

- Honor Guard

- Family Assistance Unit

- Police Chaplain

- Recruiting Division

- Staff Services Command

- Emergency Communications Division

- Jail Division

- Central Jail

- Southeast Jail

- Special Projects Unit

- Records Division

- Property Division

- Homeland Security Command

- Investigative Operations

- Office of Technology Services

- Special Investigations Command

- Auto Theft Division

- Gang Division

- Crime Reduction Unit

- Major Offenders Division

- Narcotics Division

- Vehicular Crimes Division

- Crash Investigations Unit

- Hit and Run Investigations Unit

- Auto Dealers Unit

- Vice Division

- Criminal Investigations Command

- Burglary & Theft Division

- Financial Crimes Unit

- Alarm Detail

- Pawn Detail

- Metal Theft Detail

- Homicide Division

- Murder Squads

- Major Assaults

- Juvenile Division

- Intake

- General Investigations

- Sex Offender Registration

- Missing Persons

- Robbery Division

- Special Victims Division

- Family Violence Unit

- Child Abuse Unit

- Child Sexual Abuse Unit

- Adult Sex Crimes Unit

- Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force

- Burglary & Theft Division

- Field Operations

- Mental Health Division

- General Investigations

- Crisis Intervention Response Team

- Homeless Outreach Team

- Boarding Homes Enforcement Detail

- Training

- North Patrol Command

- Central Division (District 1 except 1A10's beat and District 2)

- Downtown Division (1A10's beat)

- North Division (Districts 3 and 6)

- Northwest Division (Districts 4 and 5)

- East Patrol Command

- Eastside Division (District 11)

- Kingwood Division (District 24)

- Northeast Division (Districts 7, 8 and 9)

- Traffic Enforcement Division

- Traffic Enforcement Unit

- DWI Task Force

- Truck Enforcement Unit

- Solo Motorcycle Detail

- Mobility Response Team

- Highway Interdiction Unit

- South Patrol Command

- Clear Lake Division (District 12)

Clear Lake Station

Clear Lake Station - Southeast Division (District 13 and 14)

- South Central Division (District 10)

- Southwest Division (Districts 15 and 16)

- Clear Lake Division (District 12)

- West Patrol Command

- Midwest Division (District 18)

- South Gessner Division (District 17)

- Westside Division (Districts 19 and 20)

- Mental Health Division

Facilities

The Houston Police Department administrative offices and investigative offices are at 1200 Travis in Downtown Houston. The 61 Riesner site houses the HPD central patrol office, the municipal jail, and the transportation department. The 33 Artesia facility houses the communication and maintenance facilities.[31] In December 2013 the city announced that it has plans to build a new headquarters for HPD and the city courts.[32]

Substations and storefronts

By the end of 1989 the police department had established 19 storefronts and planned to open 10 additional storefronts in 1990.[33]

Patrol vehicles

As of 2015, the department uses a large number of Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptors as their main fleet of patrol vehicles which was first ordered in 1996 replacing the Chevrolet Caprice 9C1 (used between 1988 and in patrol service until 2004 (replacing the Ford LTD Crown Victoria squads to 1987 along with M-bodied Mopars (primarily the Plymouth Gran Fury (both R and M platform) last used in 1989)). They have Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor models from dating from 1999 to 2011. Since Ford no longer produces the "crown Vic" (procurement of the Crown Vic ended in April 2011 when the orders were filled), The department has chosen to phase in the Chevy Tahoe PPV and Ford Police Interceptor Utility(Explorer) as the successor to the Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor. The department is continuing to test new Chevy Caprice PPV models and Ford Taurus Interceptors (including the fifth-generation Explorer) as well - the test mules as of 2015 have been integrated into the mainstream vehicle fleet. It also uses pickup trucks from the Big Three, such as the Chevrolet Colorado, Ford F150, and Dodge Ram for their Truck Enforcement Unit. There is also a small fleet of Dodge Chargers and Chevrolet Camaros, which are mainly used as "stealth traffic patrol vehicles" (which is part of the Traffic Enforcement division). The stealth vehicles are plain white police cars with a slicktop roof and gray, reflective "HOUSTON POLICE" graphics on the side as well as on the front bumper, and hidden emergency lights that are driven by uniformed officers. The Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor is also used in this manner - as of late 2011 the stealth patrol vehicles are now painted black. The stealth squads have been supplemented with 14 Ford Taurus Police Interceptors in early 2014 (painted black). Solo (motorcycle) officers use Harley-Davidson motorcycles. The patrol vehicle livery, painted white with blue lettered graphics dating back to 1999 (which replaced the Columbia Blue livery last used in 1998 and retired a decade later), is being phased out for a black and white color scheme where 100 vehicles are painted from $60,000 earmarked from asset forfeiture funds (under HPD policy the previous livery is still used in service until official retirement). HPD squads are usually retired when the vehicle reaches 100,000 miles (they are not reassigned to reserve or secondary duty as with the Austin or San Antonio PD after 80,000 miles) - some squads dating over 10 model years old which are no longer used for patrol duty are usually reassigned either as bait squads (HPD will park an unmanned squad in a high crime area or illegal dumping site) or the Mobility Response Division - the older HPD fleet used by Mobility Response have been retired and replaced with Ford F150 extended cab pickup trucks from the Truck Enforcement Unit. Around 2016 the Houston Chronicle revealed that some of the older squads are still in service but the breakdown rate has increased - a 100,000 mile marked squad (or 120,000 mile unmarked vehicle) has the life expectancy of an automobile with 300,000 miles with regular maintenance. At the time HPD ordered 50 new Ford Police Interceptor Utilities for the command staff but not the mainstream vehicle fleet (the department has procured newer vehicles but the budget crunch has taken in a few new orders whilst the older squads are still operational. A budget crunch in major Texas cities is partly to blame where municipal budgets are usually slashed including priority spending for first responders. Most modern HPD Patrol cars today are Blue and white saying " HOUSTON POLICE" on the side.Newer models use a mixture of black and white paint now with 911 EMERGENCY listed on the rear side of the car or truck.

Air support

The Houston Police Helicopter Division celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2010. The unit was formed with three leased Schweizer 269B helicopters and has flown almost exclusively Schweizer or McDonnell Douglas helicopters. With 16 helicopters, the division is the second largest air support unit in the United States after the Los Angeles Police Department. In 2008 the department acquired new MD500E helicopters. The department also has Schweizer 300 helicopters for training.

The helicopter division patrols about a 700-square-mile (1,800 km2) area. HPD has two helicopters in the air for up to 21 hours a day. All pilots and tactical flight officers are sworn Houston police officers.

Weapons

Most Houston police officers now carry SIG Sauer P229, SIG Sauer P226, SIG Sauer P220, Glock 22, Glock 23 or the Smith & Wesson M&P40 .40 (S&W) caliber semi-automatic handguns. They are also armed with X26 Tasers. Tenured officers whose handguns are "grandfathered in" are still allowed to carry their weapons after the mandated .40 (S&W) requirement. This allows some officers to still carry .38 Special, .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum, and .45 Colt revolvers. Chief Charles McClelland while chief, carried a Colt 1911 Mk. IV Government Model as his sidearm. Officers are also allowed to carry an AR-15 rifle, Ruger Mini-14 rifle, Remington 870 shotgun, Benelli M1 Super 90 shotgun and a M2 Super 90 shotgun. The SWAT unit uses several kinds of automatic weapons, and was the first local law enforcement agency in the United States to adopt the FN P90. Current Chief Art Acevedo carries a Smith & Wesson M&P and it is also the standard sidearm of the Austin, Texas Police department from which he came.

As of November 2013, HPD has allowed officers to carry pistols chambered in .45ACP. The Glock 21, Sig Sauer 227, and Smith & Wesson M&P 45 are approved sidearms for uniformed officers. Plainclothes officers may carry the Glock 30 and Smith & Wesson M&P 45c. Also in 2013, HPD has begun to issue the Taser X2 in place of the Taser X26.

As of September 2015, M1911 pistols in 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP are authorized for uniformed officers as well as 9mm and .45 ACP versions of all previously authorized pistols. Plainclothes officers are now authorized to carry the Glock 43 or Smith & Wesson M&P Shield as their primary weapon.

As of January 2016, the Sig P320 in 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP is approved for uniformed officers to carry. Also, EOTech electronic optical sights have been removed from the list of red dot sights that are allowed on patrol rifles. However, Aimpoint electronic optical sights are still allowed.

Officers graduating from Cadet Class 231 or later are only authorized to carry the Sig Sauer P320, the Glock 17, or the Smith & Wesson M&P in 9mm as their primary weapon while in uniform.

The Academy, field training, and mentor program

The Houston Police Department operates a non-residential, Monday through Friday police academy from which all cadets must graduate in order to become Houston police officers.

Cadet classes last approximately six months and consist of the basic peace officer course as required by the Texas Commission of Law Enforcement (TCOLE) and HPD specific instruction. In the past, HPD has held lateral classes for officers from other agencies to become HPD officers. Lateral classes are for Police Officers who are looking to switch over to a different jurisdiction and to get credit for their experience in the field.[34]

Cadets are required to pass HPD instruction in academics, firearms, driving, physical training, and defensive tactics.

Probationary police officers (PPOs) select which available training station they will go to based on their Academy class rankings.

The following patrol stations are considered training stations:

- Clear Lake

- Central

- Eastside

- Midwest

- North

- Northeast

- South Central

- Southeast

- Southwest/South Gessner

- Westside

- Northwest

The following patrol stations are not considered training stations:

- Airport

- Kingwood

After graduation he/she is placed on a six months probation period where they will be working on a Field Training Program.[34] The Field Training Program consists of six phases and last about 12–16 weeks.[34] The Field Training occurs in the following sequence:

- Phase 1 – Three weeks of training on day shift.

- Phase 2 – Three weeks of training on evening or night shift.

- Phase 3 – Three weeks of training on evening or night shift.

- Phase 4 – Two weeks of evaluation with one week of evaluation on evening shift and one week on night shift.

- Phase 5 – Remedial training.

- Phase 6 – Re-evaluation.

PPOs that successfully complete Phase 4 are not required to continue onto Phase 5 and 6. PPOs that are required to continue onto Phase 5 are given remedial training in the category or categories that they are deemed deficient in. If a PPO fails Phase 6, they are disqualified from becoming a police officer, and must reapply to the department. Phase 6 is required to ensure that they have corrected the deficiency.

After completing the Field Training Program, PPOs are partnered with mentor officers for approximately 4 months.Their first assignment after completing Field Training is a Patrol Officer.[34] The Mentor Program is not a graded or pass/fail program. Instead, it is designed to give PPOs additional guidance before they are allowed to patrol on their own after their probationary period.

The probationary period for PPOs last for one year from the date that they were hired on as cadets. At their one-year anniversary, officers become civil service protected.

Officers select their permanent assignments based on Academy class rank. Officers must serve in their permanent assignment for at least one year before they can transfer to another division.

New sergeants and lieutenants receive leadership in-service training colloquially known as going to "Sergeant School" and "Lieutenant School", respectively.

Newly promoted sergeants must undergo a separate field training program. They are trained for 3 weeks on one shift and then another 3 weeks on another shift. They are then evaluated for 1 week on one shift and then for another week on another shift. This training is designed to ensure that they can perform effectively as new supervisors.

New sergeants pick available training and permanent assignments based on their ranking on their promotion list.

Multilingual services

Demand for use of Vietnamese-speaking officers increased in the 1980s as the city's Vietnamese population increased. By 1997, according to Sergeant Bill Weaver, in addition to English and Spanish, HPD had officers who had fluency in Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, and Vietnamese. HPD has a dispatch system tracking officers speaking languages other than English and Spanish.[35]

Ranks

These are the current ranks of the Houston Police Department:

| Rank | Insignia |

|---|---|

| Chief | |

| Executive Assistant Chief | |

| Assistant Chief | |

| Commander | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Sergeant | |

| Senior Police Officer | |

| Police Officer | N/A |

Those with the rank of sergeant or above are supervisors and are issued gold badges whereas officers are issued silver badges.

Lieutenants and above may also be referred to as commanders. For example, they hold position titles including "shift commander", "night commander", "division commander", etc. They are also exempt employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act due to their managerial responsibilities.

After 12 years of HPD service and obtaining a TCOLE Master Peace Officer certification, an officer becomes a senior officer.[36] This rank was created in 2001.[37]

Promotion to sergeant through captain all occur via a civil service formula that factors into account performance on the written examination for the respective rank, assessment score, years of service, and level of higher education or 4 years of military service. Officers are eligible to take the sergeant's promotion exam after 5 years of service. Sergeants and lieutenants are eligible to take the promotion exam of the next higher rank after 2 years of service in their current rank. Candidates for lieutenant must hold at least 65 college hours or an associate degree. Candidates for the rank of commander must hold at least a bachelor's degree.[36]

Assistant chiefs and executive assistant chiefs are appointed by the chief with the approval of the mayor. Such individuals must hold at least a master's degree and have 5 years of HPD service.[36]

It is not required to move through every rank below to achieve a higher rank. For example, many officers promote directly to sergeant without ever being senior officers. Also, many assistant chiefs are promoted directly from the rank of lieutenant. Councilman C.O. Bradford was promoted to assistant chief from the rank of sergeant.[38] Jack Heard was promoted to chief from the rank of sergeant.[39] It is entirely possible to become chief as an outsider such as in the case of Lee Brown, who went on to become mayor, and Harold Hurtt.

Defunct ranks include detective, commissioner, captain, inspector, and deputy chief. In the mid 1980s, all active duty detectives were reclassified to sergeants.[40] Originally, officers could choose to promote to detective (investigator) or sergeant (supervisor) which were both immediately below lieutenant.[41]

Currently, the title of "Detective" more accurately refers to certain investigators. Eligibility requirements include:

- holding the rank of officer, senior officer, or sergeant

- being assigned to a qualifying investigative division

- carrying a significant case load as determined by a supervisor

- having at least 4 years of Department seniority

- having at least 1 year of cumulative HPD investigative experience

- having completed the Basic Investigator's course and one additional investigative course

Per policy, when an investigator from the concerned investigative division arrives to a patrol scene, the investigator shall take charge of the investigation.

In 2018, the rank of captain was converted to commander with a change of rank insignia from double gold bars to one gold star.

George Seber was promoted to assistant chief in either 1953 or 1954[42] and was second in command of the department.[41] However, that rank ended when he left in 1969.[42][43] Inspectors were then the second highest ranking[41] and Chief Pappy Bond converted that rank to deputy chief.[43] After the rank of assistant chief was re-instituted in the mid 1970s,[40] the deputy chief rank was third highest for a time. Circa 1990, the rank of deputy chief was abolished. In 1998, the executive assistant chief rank was created,[44] making it the second highest rank.

Supervisors may also be appointed under certain circumstances to act in the next higher rank during an absence from duty of their supervisor. For example, a patrol sergeant might be appointed as the acting lieutenant (shift commander) if there would be no other lieutenants on duty within that division. Per policy, officers cannot be appointed as acting sergeants (supervisors).

Fallen officers

Since the establishment of the Houston Police Department, 115 officers have died in the line of duty. The following list also contains officers from the Houston Airport Police Department and the Houston City Marshal's Office, which were merged into HPD.[45][46][47]

The causes of death are as follows:

| Cause of death | Number of deaths |

|---|---|

| Assault | |

| Automobile accident | |

| Fire | |

| Gunfire | |

| Gunfire (Accidental) | |

| Heart attack | |

| Motorcycle accident | |

| Stabbed | |

| Struck by vehicle | |

| Vehicle pursuit | |

| Vehicular assault | |

| Helicopter crash |

The Houston Police Officers Memorial, designed by Texas artist Jesús Moroles, opened in 1991 to honor the duty and sacrifices of the department.

Demographics

Breakdown of the makeup of the rank and file of HPD:[48]

- Male: 88%

- Female: 12%

- White: 37%

- African-American/Black: 42%

- Hispanic: 18%

- Asian: 3%

Misconduct

Joe Campos Torres

In May 1977, Joe Campos Torres (1954 - May 5, 1977) was a 23-year-old Vietnam veteran who was arrested for disorderly conduct at a bar in Houston's predominantly Hispanic East End neighborhood. Six Houston police officers took Torres to a spot called "The Hole" next to Buffalo Bayou and beat him.The officers then took Torres to the city jail, where they were ordered to take him to the hospital. Instead of taking Torres to the hospital like they were told, the officers brought him back to the banks of Buffalo Bayou, where he was pushed into the water. Torres' body was found two days later.[49]

Chad Holley Beating

Chad Holley was an Elsik High School sophomore at the time of his arrest in March 2010, as an alleged burglary suspect, which was preceded by, what some say,[50] was an abuse by HPD. He was eventually found guilty and sentenced to probation until he turned 18.[51] The incident also resulted in 12 officers disciplined, fired, or charged. All appealed the decisions.[52] Officer Andrew Blomberg, the first of four officers to go on trial, has been acquitted of charges of "Official Oppression".[53]

Tracie Bell

In September 2010, Officer Tracie Bell was sentenced to sixteen years in prison for stealing over $100,000 from American Red Cross funds earmarked for survivors of hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Bell and another officer contracted with the charity to run a basketball camp for young people displaced by the storms. They inflated the number of persons they claimed attended in order to gain additional funds.[54]

Ruben Trejo

In April 2011, Sergeant Ruben Trejo crashed his private vehicle into a school bus while driving to work. Tests showed he had twice the legal limit of alcohol in his blood. Sergeant Trejo was fired.[55][56]

Rape kits

In August 2011, press reports indicated that the department held more than 7,000 rape kits that had never been tested. Some of these kits dated back twenty years.[57]

Abraham Joseph

In October 2012, Officer Abraham Joseph was sentenced to life in prison for raping a handcuffed woman in the back of his police car. During the sentencing phase of the trial, two other women came forward to claim the policeman also raped them.[58]

Shooting of a double amputee

In June 2013, a grand jury refused to indict Officer Matthew Marin after he shot and killed Brian C. Claunch on 22 September 2012. Claunch, who was mentally ill and confined to a wheelchair threatened a police officer with a ballpoint pen. Marin then killed him.[59]

Darrin DeWayne Thomas

In August 2013, Officer Darrin DeWayne Thomas pleaded guilty to the theft of $700. Thomas was caught in an October 2010 sting operation where he thought he had been left with the money unobserved. He was sentenced to two years of probation and agreed to surrender his Texas peace officer's license. After he finishes his period of probation, he will have no criminal record.[60]

Adan Jimenez Carranza

In October 2013, Officer Adan Jimenez Carranza plead guilty to "attempted sexual assault" for raping a woman in the back of his patrol car after investigating a minor traffic accident. He was sentenced to ten years in prison and twenty years on the state's sex offender registry. Carranza could be eligible for parole in six months.[61]

Gerald Goines

In late February 2020, the Harris County District Attorney ask local courts to appoint lawyers to represent sixty-nine people who had been convicted based on the testimony of Officer Gerald Goines. Goines had made false statements to obtain a warrant the resulted in two deaths in January 2019. This misconduct through into doubt a number of legal actions based upon his testimony.[62]

Education

Breakdown of the types of academic degrees held by HPD members:[63]

- Associate degree: 311

- Bachelor's Degree: 1750

- Master's Degree: 575

- Doctorate Degree: 46

- Total number of members with a degree: 2,682

HPD Big awards

- Chief of Police Commendation: may be presented to any department employee who demonstrated a high degree of professional excellence or initiative through the success of initiating, developing, or implementing difficult projects, programs, or investigations. The performance shall not have involved personal hazard to the individual.

- Medal of Valor: may be presented to officers who judiciously performed voluntary acts of conspicuous gallantry and extraordinary heroism above and beyond the call of duty, knowing that taking such action presented a clear threat to their lives.

- Lifesaving Award: may be presented to any classified or civilian employee when a person would more than likely have died or suffered permanent brain damage if not for the employee's actions. The act must clearly indicate the employee did at least one of the following: (a) rendered exceptional first aid or (b) made a successful rescue (e.g. from a burning building or vehicle, or from drowning).

- Blue Heart Award: may be presented to officers who received life-threatening injuries while acting judiciously and in the line of duty. Officers may be eligible to receive the Blue Heart Award in conjunction with another award such as the Meritorious Service Award or the Lifesaving Award. Injuries due to negligence or minor injuries not requiring hospitalization are not eligible.

- Meritorious Service Award: may be presented to officers who have distinguished themselves by one of the following: (a) conduct during a criminal investigation or law enforcement action while demonstrating a high level of courage or (b) actions resulting in the apprehension of a felon under dangerous or unusual circumstances.

- Award of Excellence: may be presented to classified or civilian employees who have distinguished themselves on or off duty by outstanding service to HPD or the community. Employees must have demonstrated a high degree of dedication and professionalism in an endeavor that does not meet any other award criteria.

- Hostile Engagement Award: may be presented to officers who acted judiciously in the line of duty and performed acts upholding the high standards of the law enforcement profession while engaging in hostile confrontations with suspects wielding deadly weapons. Individuals who sustained non-life-threatening or minor injuries resulting from an assault by a deadly weapon are also eligible.

- Humanitarian Service Award: may be presented to any individual (employee or not) who demonstrated a voluntary act of donating time, physical effort, financial support, or special talent promoting the safety, health, education, or welfare of citizens. The individual is not eligible if there was any personal gain, financial compensation, special services, or privileges in exchange for the act.

- Public Service Award: may be presented to any individual outside the department who voluntarily acted in circumstances requiring unusual courage or heroism while assisting a police officer or other citizen. Those who do not meet the above criteria, but provided a measure of assistance, shall be sent a letter and a Certificate of Appreciation (no citation page) signed by the Chief of Police.

- Chief of Police Unit Citation: may be presented to two or more employees who performed an act or a series of acts over a period of time that demonstrated exceptional bravery or outstanding service to the department or the community. Their combined efforts as a functioning team must have resulted in the attainment of a departmental goal(s) and increased the department's effectiveness and efficiency.

Radio Unit Identifiers

Numeric-only Identifiers

- 5xx Mayor's Protection Detail

- 12xx Criminal Intelligence Division

- 16xx Tactical Operations Division

- 17xx Major Offenders

- 19xx Robbery

- 20xx Dignitary Protection Details

- 26xx Narcotics

- 30xx Vice

- 35xx Special Victims

- 36xx City Wreckers/Transportation

- 47xx Juvenile

Alphanumeric Identifiers

- x-Y-xx Special Operations Patrol (Downtown, Parks, Special Events)

- x-Y-xx-T Special Operations Patrol (Downtown and Parks) Power Shift

- 10-Y-xx Special Operations Patrol - Memorial Park

- 20-Y-xx Special Operations Patrol - Hermann Park

- 24-P-xx Lake Houston Patrol

- 3x-x-xx Special Event Details

- 4x-x-xx Special Event Details

- 30-T-xx Traffic Enforcement Special Details

- 40-T-xx Traffic Enforcement Special Details

- 60-T-xx Traffic STEP Enforcement

- 66-M-xx Crisis Intervention Response Team

- 70-Z-xx Vehiclar Crimes Division

- 71-Z-xx Truck Enforcement Unit

- 73-I-xx Canine - IAH Airport

- 73-K-xx Canine - Patrol

- 75-Z-xx Mobility Response Team ("Scooters")

- 79-T-xx Truck STEP Enforcement

- 86-M-xx City Marshals - Municipal Court

- 90-x-xx Patrol Division Tactical Units

- 91-x-xx Investigative First Responders

- 92-x-xx Patrol Division Tactical Units

- 96-Z-xx DWI Task Force

- 97-Z-xx Radar Task Force

- 99-Z-xx Motorcycles

See also

- List of law enforcement agencies in Texas

- Houston Blue - A book about the police department

- Crime in Houston

References

- Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- "Houston Police Department". Houstonpolice.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- http://www.khou.com/mb/news/local/new-hpd-chief-to-be-sworn-in-wednesday/359212808

- http://www.policelawblog.com/files/2012-acevedo-case.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Duncan, Robert J. (13 June 2013). "Duty, Margie Annette Hawkins". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "TWC News - Austin". News8austin.com. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- Kriel, Lomi (23 March 2017). "Harris County drops to No. 2 nationally in population growth, according to Census data". The Houston Chronicle.

- "2010 Statistics Report". Chicago Police Department. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Adam Liptak (2003-03-11). "Worst Crime Lab in the Country?". Truthinjustice.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- Bromwich, Michael R. "Final Report of the Independent Investigator for the Houston Police Department Crime Laboratory and Property Room" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- "Houston Crime Lab Under Fire Again". Fox News. 2006-01-05. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "HPD's crime lab faces proficiency-test inquiry - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "SAFEClear - Home Page". Houstontx.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Hurtt calls for cameras to catch traffic violators - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. 2004-04-30. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Red-light ordinance faces fight in Austin / Lawmaker has filed a bill to kill the camera plan; privacy, fairness cited as concerns 12/24/2004 HOUSTON CHRONICLE, Section B, Page 01 metfront, 3 STAR Edition

- "Citations to start going out for red light runners". KTRK-TV. 2011-07-21. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- Pinkerton, James (2011-07-22). "Houston". Chron.com. Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- "Civilian officers on scooters will fight Inner Loop gridlock - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- HPD'S WAR ON CRIME GOES INTO OVERTIME / City promises 564 more officers, $24 million for OT 10/03/2007 Houston Chronicle, Section A, Page 1, 3 STAR Edition

- Hassan, Anita and Jennifer Leahy. "Acres Homes search to focus on dumped bodies cases." Houston Chronicle. Saturday October 6, 2007. B2. Retrieved on August 29, 2009.

- Stiles, Matt and Kevin Moran. "HPD'S WAR ON CRIME GOES INTO OVERTIME / City promises 564 more officers, $24 million for OT." Houston Chronicle. Wednesday October 3, 2007. A1. Retrieved on August 29, 2009.

- DePrang, Jo (2013-09-04). "The Horror Every Day: Police Brutality In Houston Goes Unpunished". Texas Observer. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "HPD helicopter crashes in north Houston injuring 2 officers". www.click2houston.com. KPRC-TV. 2020-05-02. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Apocada, Gene. "HPD to make major changes Archived 2014-04-29 at the Wayback Machine." KTRK-TV. Friday February 8, 2008. Retrieved on April 9, 2010.

- Morris, Mike. "City plans 'hugely important' new justice complex." Houston Chronicle. December 26, 2013. Retrieved on April 30, 2014.

- Hillkirk, John and Gary Jacobson. Grit, Guts, and Genius: True Tales of Megasuccess : Who Made Them Happen And How They Did It. Houghton Mifflin, 1990. 123. Retrieved from Google Books on January 8, 2012. ISBN 0-395-56189-2, ISBN 978-0-395-56189-8. "By late 1989, the Houston Police Department had established nineteen storefronts, with ten more scheduled to open in 1990."

- "Academy". Hpdcareer.com. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- Hanson, Eric. "No failure to communicate with the police / HPD's multilingual officers discover language talents often useful, necessary." Houston Chronicle. Monday, September 29, 1997. p. 13 Metfront. Available from NewsBank, Record Number HSC09291441397. Available online from the Houston Public Library with a library card.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bradford retiring, cites wife's pregnancy With audio - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. 2003-07-18. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Jack Heard, former HPD chief, dies at 87 - Houston Chronicle". M.chron.com. 2005-04-17. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Houston Public Library Digital Archives". Digital.houstonlibrary.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Houston Police Department, Texas, Fallen Officers". Odmp.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Houston Airport Police Department, Texas, Fallen Officers". Odmp.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Houston City Marshal's Office, Texas, Fallen Officers". Odmp.org. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Nation: End of the Rope". Time Magazine. Apr 17, 1978. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- Oaklander, Mandy (Feb 9, 2011). "Chad Holley's Police Beating Is Subject of an Angry NAACP Town Hall Meeting". Houston Press. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- Willey, Jessica (October 26, 2010). "Jury reaches verdict in Chad Holley's trial". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- "4 charged, 7 fired, 12 disciplined in HPD". Houston Chronicle. June 23, 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- "Not guilty verdict in case against ex-Houston officer Andrew Blomberg". KTRK-TV. 2012-05-16. Archived from the original on 2012-05-20. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- "FORMER COP...CONVICTED THIEF GETS 16 YEAR PRISON TERM - dm.news". Druzifer.livejournal.com. 2010-09-24. Archived from the original on 2014-01-07. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- HPD punishes 7 officers for conduct in wreck, by James Pinkerton, September 20, 2011, Houston Chronicle

- Houston cop injured in crash with schoolbus, by khou.com staff, April 13, 2011

- HPD rape case backlog is far worse than feared; Crime lab finds another 3,000-plus untested rape kits;'Disgraceful,' activist says after HPD inventory, by Anita Hassan, 9 August 2011, Houston Chronicle

- Jurors sentence ex-HPD cop to life in prison for raping waitress, by Kevin Reece, 8 October 2012, KHOU 11 News

- No charges against HPD officer who killed double amputee in a wheelchair, by James Pinkerton, Houston Chronicle June 13, 2013

- Former HPD officer pleads guilty in a theft sting, by Brian Rogers, August 9, 2013, Houston Chronicle

- Former HPD cop pleads guilty in rape case, by Brian Rogers, Houston Chronicle, 15 October 2013

- Barned-Smith, St. John (26 February 2020). "69 convicted solely on disgraced ex-Houston cop's 'evidence' could see new trials, DA says". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Houston Police Department. |

- Official website of the Houston Police Department

- Official website of the Houston Police Officers' Union