Tower of Silence

A dakhma, also known as the Tower of Silence, is a circular, raised structure built by Zoroastrians for excarnation – that is, for dead bodies to be exposed to carrion birds, usually vultures.

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

Atar (fire), a primary symbol of Zoroastrianism |

|

Primary topics |

|

Divine entities

|

|

Scripture and worship |

|

Accounts and legends |

|

Related topics |

|

|

Zoroastrian exposure of the dead is first attested in the amid of the 5th century BC Histories of Herodotus, but the use of towers is first documented in the early 9th century CE. 156–162 The doctrinal rationale for exposure is to avoid contact with Earth or Fire, both of which are considered sacred in the Zoroastrian religion.

One of the earliest literary descriptions of such a building appears in the late 9th-century Epistles of Manushchihr, where the technical term is astodan, "ossuary". Another technical term that appears in the 9th/10th-century texts of Zoroastrian tradition (the so-called "Pahlavi books") is dakhmag, for any place for the dead.

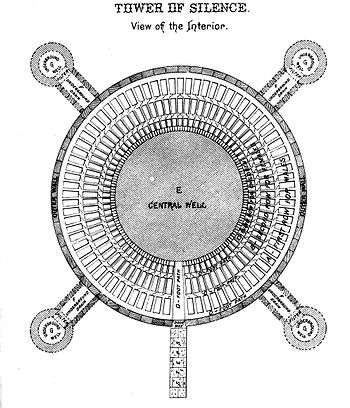

The modern-day towers, which are fairly uniform in their construction, have an almost flat roof, with the perimeter being slightly higher than the centre. The roof is divided into three concentric rings: the bodies of men are arranged around the outer ring, women in the second circle, and children in the innermost ring. Once the bones have been bleached by the sun and wind, which can take as long as a year, they are collected in an ossuary pit at the centre of the tower, where – assisted by lime – they gradually disintegrate, and the remaining material – with run-off rainwater – runs through multiple coal and sand filters before being eventually washed out to sea.

Rationale

Zoroastrian tradition considers a dead body (in addition to cut hair and nail parings) to be nasu, unclean, i.e. potential pollutants. Specifically, the corpse demon (Avestan: nasu.daeva) was believed to rush into the body and contaminate everything it came into contact with,[1] hence the Vendidad (an ecclesiastical code "given against the demons") has rules for disposing of the dead as safely as possible.

To preclude the pollution of earth or fire (see Zam and Atar respectively), the bodies of the dead are placed atop a tower and so exposed to the sun and to scavenging birds. Thus, "putrefaction with all its concomitant evils... is most effectually prevented."[2]

History

Zoroastrian ritual exposure of the dead is first known of from the writings of the mid-5th century BCE Herodotus, who observed the custom amongst Iranian expatriates in Asia Minor. In Herodotus' account (Histories i.140), the rites are said to have been "secret", but were first performed after the body had been dragged around by a bird or dog. The corpse was then embalmed with wax and laid in a trench.[3]:204

While the discovery of ossuaries in both eastern and western Iran dating to the 5th and 4th centuries BCE indicates that bones were isolated, that this separation occurred through ritual exposure cannot be assumed: burial mounds,[4] where the bodies were wrapped in wax, have also been discovered. The tombs of the Achaemenid emperors at Naqsh-e Rustam and Pasargadae likewise suggest non-exposure, at least until the bones could be collected. According to legend (incorporated by Ferdowsi into his Shahnameh), Zoroaster is himself interred in a tomb at Balkh (in present-day Afghanistan).

Writing on the culture of the Persians, Herodotus reports on the Persian burial customs performed by the Magi, which are kept secret. However, he writes that he knows they expose the body of male dead to dogs and birds of prey, then they cover the corpse in wax, and then it is buried.[5] The Achaemenid custom is recorded for the dead in the regions of Bactria, Sogdia, and Hyrcania, but not in Western Iran.[6]

The Byzantine historian Agathias has described the burial of the Sasanian general Mihr-Mihroe: "the attendants of Mermeroes took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion".[6]

Towers are a much later invention and are first documented in the early 9th century CE.[7]:156–162 The ritual customs surrounding that practice appear to date to the Sassanid era (3rd – 7th century CE). They are known in detail from the supplement to the Shayest ne Shayest, the two Rivayat collections, and the two Saddars.

Construction

_006.jpg)

The modern-day towers, which are fairly uniform in their construction, have an almost flat roof, with the perimeter being slightly higher than the centre. The roof is divided into three concentric rings: the bodies of men are arranged around the outer ring, women in the second circle, and children in the innermost ring. Once the bones have been bleached by the sun and wind, which can take as long as a year, they are collected in an ossuary pit at the centre of the tower, where – assisted by lime – they gradually disintegrate, and the remaining material – with run-off rainwater – runs through multiple coal and sand filters before being eventually washed out to sea. The ritual precinct may be entered only by a special class of pallbearers, called nusessalars, a contraction of nasa.salar, caretaker (-salar) of potential pollutants (nasa-).

In current times

In Iran

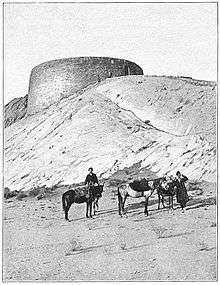

In the Iranian Zoroastrian tradition, the towers were built atop hills or low mountains in desert locations distant from population centers. In the early twentieth century, the Iranian Zoroastrians gradually discontinued their use and began to favour burial or cremation.

The decision to change the system was accelerated by three considerations: the first problem arose with the establishment of the Dar ul-Funun medical school. Since Islam considers unnecessary dissection of corpses as a form of mutilation, thus forbidding it, there were no corpses for study available through official channels. The towers were repeatedly broken into, much to the dismay of the Zoroastrian community. Secondly, while the towers had been built away from population centers, the growth of the towns led to the towers now being within city limits. Finally, many of the Zoroastrians found the system outdated. Following long negotiations between the anjuman societies of Yazd, Kerman, and Tehran, the latter gained a majority and established a cemetery some 10 km from Tehran at Ghassr-e Firouzeh (Firouzeh's Palace). The graves were lined with rocks and plastered with cement to prevent direct contact with the earth. In Yazd and Kerman, in addition to cemeteries, orthodox Zoroastrians continued to maintain a tower until the 1970s when ritual exposure was prohibited by law.

In India

Following the rapid expansion of the Indian cities, the squat buildings are today in or near population centers, but separated from the metropolitan bustle by gardens or forests. In Parsi Zoroastrian tradition, exposure of the dead is also considered to be an individual's final act of charity, providing the birds with what would otherwise be destroyed.

In the late 20th century and early 21st century the vulture population on the Indian subcontinent declined (see Indian vulture crisis) by over 97% as of 2008, primarily due to diclofenac poisoning of the birds following the introduction of that drug for livestock in the 1990s,[8] until banned for cattle by the Indian government in 2006. The few surviving birds are often unable to fully consume the bodies.[9] In 2001, Parsi communities in India were evaluating captive breeding of vultures and the use of "solar concentrators" (which are essentially large mirrors) to accelerate decomposition.[10] Some have been forced to resort to burial, as the solar collectors work only in clear weather. Vultures used to dispose of a body in minutes, and no other method has proved fully effective.

The right to use the Towers of Silence is a much-debated issue among the Parsi community (see Parsi for details). The facilities are usually managed by the anjumans, the predominantly conservative local Zoroastrian associations (usually having five priests on a nine-member board). In accordance with Indian statutes, these associations have domestic authority over trust properties and have the right to grant or restrict entry and use, with the result that the associations frequently prohibit the use by the offspring of a "mixed marriage", that is, where one parent is a Parsi and the other is not.

See also

- Seth Modi Hirji Vachha

- Sky burial

References

- Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1928), The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees, Anthropological Society of Bombay, archived from the original on 2005-02-07, retrieved 2005-09-09

- Stausberg, Michael (2004), "Bestattungsanlagen", Die Religion Zarathushtras, 3, Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag, pp. 204–245.

- Falk, Harry (1989), "Soma I and II", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS), 52 (1): 77–90, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00023077

- "HERODOTUS iii. DEFINING THE PERSIANS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater, Routledge & Kegan Paul Volume 6, Parts 1-3, page 281a

- Boyce, Mary (1979), Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London: Routledge, pp. 156–162.

- Tait, Malcolm (January 10, 2004), India's vulture population is facing catastrophic collapse and with it the sacrosanct corporeal passing of the Parsi dead, London: The Ecologist, archived from the original on September 27, 2007

- Swan, Gerry; et al. (2006), "Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures", PLoS Biology, 4 (3): e66, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066, PMC 1351921, PMID 16435886

- Srivastava, Sanjeev (18 July 2001), "Parsis turn to solar power", BBC News South Asia, archived from the original on 30 June 2006, retrieved 9 September 2005

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Towers of Silence. |

- Vendidad Fargard 5, Purity Laws, as translated by James Darmesteter.

- Extracts from

- Wadia, Azmi (2002), "Evolution of the Towers of Silence and their Significance", in Godrej, Pheroza J.; Mistree, Firoza Punthakey (eds.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, New York: Mapin

- Kotwal, Firoze M.; Mistree, Khojeste P. (2002), "Protecting the Physical World", in Godrej, Pheroza J.; Mistree, Firoza Punthakey (eds.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, New York: Mapin, pp. 337–365

- Lucarelli, Fosco "Towers of Silence: Zoroastrian Architectures for the Ritual of Death", "Socks-Studio", Feb 9, 2012

- Harris, Gardiner "Giving New Life to Vultures to Restore a Human Ritual of Death", "The New York Times", Nov 29, 2012