Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of the Free Grace theology of Puritan minister John Cotton. The most notable Free Grace advocates, often called "Antinomians", were Anne Hutchinson, her brother-in-law Reverend John Wheelwright, and Massachusetts Bay Governor Henry Vane. The controversy was a theological debate concerning the "covenant of grace" and "covenant of works".

Anne Hutchinson at trial and John Winthrop | |

| Date | October 1636 to March 1638 |

|---|---|

| Location | Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Participants | Free Grace Advocates (sometimes called "Antinomians")

Magistrates Ministers

|

| Outcome |

|

Anne Hutchinson has historically been placed at the center of the controversy, a strong-minded woman who had grown up under the religious guidance of her father Francis Marbury, an Anglican clergyman and school teacher. In England, she embraced the religious views of dynamic Puritan minister John Cotton, who became her mentor; Cotton was forced to leave England and Hutchinson followed him to New England.

In Boston, Hutchinson was influential among the settlement's women and hosted them at her house for discussions on the weekly sermons. Eventually, men were included in these gatherings, such as Governor Vane. During the meetings, Hutchinson criticized the colony's ministers, accusing them of preaching a covenant of works as opposed to the covenant of grace espoused by Reverend Cotton. The Colony's orthodox ministers held meetings with Cotton, Wheelwright, and Hutchinson in the fall of 1636. A consensus was not reached, and religious tensions mounted.

To ease the situation, the leaders called for a day of fasting and repentance on 19 January 1637. However, Cotton invited Wheelwright to speak at the Boston church during services that day, and his sermon created a furor which deepened the growing division. In March 1637, the court accused Wheelwright of contempt and sedition, but he was not sentenced. His supporters circulated a petition on his behalf, mostly people from the Boston church.

The religious controversy had immediate political ramifications. During the election of May 1637, the free grace advocates suffered two major setbacks when John Winthrop defeated Vane in the gubernatorial race, and some Boston magistrates were voted out of office for supporting Hutchinson and Wheelwright. Vane returned to England in August 1637. At the November 1637 court, Wheelwright was sentenced to banishment, and Hutchinson was brought to trial. She defended herself well against the prosecution, but she claimed on the second day of her hearing that she possessed direct personal revelation from God, and she prophesied ruin upon the colony. She was charged with contempt and sedition and banished from the colony, and her departure brought the controversy to a close. The events of 1636 to 1638 are regarded as crucial to an understanding of religion and society in the early colonial history of New England.

The idea that Hutchinson played a central role in the controversy went largely unchallenged until 2002, when Michael Winship's account portrayed Cotton, Wheelwright, and Vane as complicit with her.

Background

Antinomianism literally means being "against or opposed to the law"[1] and was a term used by critics of those Massachusetts colonists who advocated the preaching of "free grace". The term implied behavior that was immoral and heterodox, being beyond the limits of religious orthodoxy.[1] The free grace advocates were also called Anabaptists and Familists, groups that were considered heretical in New England. All three of these terms were used by magistrate John Winthrop in his account of the Antinomian Controversy called the Short Story.[1]

The conflict initially involved a difference in views concerning "religious works" or behavior, as well as the presence and role of the Holy Spirit. For example, the Puritan majority held the view that an individual's salvation is demonstrated by righteous behavior or "good works," while the Antinomians argued that one's spiritual condition had no bearing upon one's outward behavior. However, the debate quickly changed, as the Antinomians began to claim that personal revelation was equivalent to Scripture, under the influence of Anne Hutchinson's teachings, while the Puritan majority held that the Bible was the final authority, taking precedence over any personal viewpoints.

Winthrop had given the first public warning of this problem around 21 October 1636, and it consumed him and the leadership of the Massachusetts Bay Colony for much of the next two years.[2] He wrote in his journal, "One Mrs. Hutchinson, a member of the church at Boston, a woman of a ready wit and a bold spirit, brought over with her two dangerous errors: 1. That the person of the Holy Ghost dwells in a justified person. 2. That no sanctification ["works"] can help to evidence to us our justification."[3] He then went on to elaborate these two points. This is usually considered the beginning of the Antinomian Controversy,[3] which has more recently been called the Free Grace Controversy.[4]

"Free Grace" advocates

Anne Hutchinson came to be near the center of the controversy. Emery Battis suggests that she induced "a theological tempest which shook the infant colony of Massachusetts to its very foundations".[5] John Wheelwright was also deeply involved, Hutchinson's relative through marriage and a minister with a "vigorous and contentious demeanor".[5] The early writers on the controversy blamed most of the difficulties on Hutchinson and Wheelwright, but Boston minister John Cotton and magistrate Henry Vane were also deeply complicit in the controversy.[6]

Cotton had been a mentor to Hutchinson, and the colony's other ministers regarded him and his parishioners with suspicion because of his teachings concerning the relative importance of a Christian's outward behavior. Vane was a young aristocrat who brought his own unconventional theology to the colony, and he may have encouraged Hutchinson to lead the colony's women and develop her own divergent theology.[7] Ultimately, Hutchinson and Wheelwright were banished from the colony with many of their supporters, and Vane departed for England as the controversy came to a head. Cotton, however, was asked to remain in Boston, where he continued to minister until his death.[8]

Anne Hutchinson

Hutchinson (1591–1643) was the daughter of Francis Marbury, a school teacher and Anglican clergyman in England with strong Puritan leanings. She was deeply imbued with religious thought as a youngster, but as a young woman had come to mistrust the priests of the Church of England who did not seem to act according to their principles.[9] Her religious beliefs were leaning toward atheism when she claimed to hear the voice of God, and "at last he let me see how I did oppose Jesus Christ… and how I did turne in upon a Covenant of works… from which time the Lord did discover to me all sorts of Ministers, and how they taught, and to know what voyce I heard".[10] From this point forward, this inner voice became the source of her guidance.[10]

Hutchinson became a follower of John Cotton who preached at St. Botolph's Church in Boston, Lincolnshire, about 21 miles (34 km) from her home town of Alford, Lincolnshire in eastern England.[10] It was likely Cotton who taught her to question the preaching of most early 17th-century English clergymen.[10] Cotton wrote, "And many whose spiritual estates were not so safely layed, yet were hereby helped and awakened to discover their sandy foundations, and to seek for better establishment in Christ".[10]

Not long after her arrival in Boston, Hutchinson began inviting women to her house to discuss recent sermons and other religious matters, and eventually these became large gatherings of 60 or more people twice a week.[11] They gathered at these conventicles to discuss sermons and to listen to Hutchinson offer her spiritual explanations and elaborations, but also to criticize members of the colony's ministers.[12] Hutchinson began to give her own views on religion, espousing that "an intuition of the Spirit" rather than outward behavior provided the only proof that one had been elected by God.[12] Her theological views differed markedly from those of most of the colony's Puritan ministers.

Hutchinson's following soon included Henry Vane, the young governor of the colony, along with merchants and craftsmen who were attracted to the idea that one's outward behavior did not necessarily affect one's standing with God.[12] Historian Emery Battis writes, "Gifted with a magnetism which is imparted to few, she had, until the hour of her fall, warm adherents far outnumbering her enemies, and it was only by dint of skillful maneuvering that the authorities were able to loosen her hold on the community."[5]

Beliefs

Hutchinson took Cotton's doctrines concerning the Holy Ghost far beyond his teachings, and she "saw herself as a mystic participant in the transcendent power of the Almighty."[13] Her theology of direct personal revelation opposed the belief that the Bible was the final authority concerning divine revelation, which was basic to the Reformed doctrines held by the majority of English settlers at that time. She also adopted Cotton's minority view that works, behavior, and personal growth are not valid demonstrations of a person's salvation. She went beyond this, however, and espoused some views that were more radical, devaluing the material world and suggesting that a person can become one with the Holy Spirit.[14] She also embraced the heterodox teaching of mortalism, the belief that the soul dies when the body dies,[14] and she saw herself as a prophetess. She had prophesied that God was going to destroy England, and she prophesied during her trial that God would destroy Boston.[14]

Background to the theological struggle

Hutchinson challenged a major teaching of the Protestant communion by claiming to receive direct revelation that was equal in authority to Scripture. Orthodox theology states that the Bible holds ultimate authority rather than personal revelation, a position known as "sola scriptura". She also taught that Christian liberty gave one license to ignore Scriptural teachings, directly opposing the teachings of Reformed faith.

The struggle between Hutchinson and the magistrates was an echo of a larger struggle throughout the Christian world between those who believed in direct, personal, and continuing revelation from God (Anabaptists) and those who believed that the Bible represented the final authority on revelation from God (Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism). At its heart was the question of where ultimate authority rests. The Catholic Church believes that ultimate authority rests in both scripture and in the church. General revelation concluded at the end of the Apostolic Age, and "the full truth of Revelation is contained in the doctrine of the Apostles;" this, in Catholic teaching, is preserved by the church "unfalsified through the uninterrupted succession of the bishops."[15] In contrast, the Reformers claimed that authority rested in scripture alone. In this light, Hutchinson's assertion to have received authoritative revelations which other Christians should obey was not a gender issue at all; it was an important doctrinal point of contention. Many English Reformers had been martyred defending such doctrines as sola scriptura, including Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley.[16]

Twenty years after the Antinomian Controversy in 1659, Puritan Theologian John Owen wrote a critique of another religious movement known as the Quakers. Owen's opening words in A Defense of Sacred Scripture against the Fanatics reflect beliefs on the authority and sufficiency of Scripture generally held by Reformed people:

The Scriptures are the settled, ordinary [vs. extraordinary], perfect [cannot be improved upon], and unshakable rule for divine worship and human obedience, in such a fashion that leaves no room for any other, and no scope for any new revelations whereby man may be better instructed in the knowledge of God and our required duty.[17]

It was in this context that the magistrates reacted to Anne Hutchinson's claim of receiving divine, authoritative revelations.

John Wheelwright

Another major player who sided with the Antinomians was Hutchinson's brother-in-law John Wheelwright, who had just arrived in New England in May 1636 as the controversy was beginning. Wheelwright was characterized as having a contentious disposition, and he had been the pastor of a church within walking distance of Hutchinson's home town of Alford.[18] He was educated at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, receiving his B.A. in 1615 and his M.A. in 1618.[19] A friend and college mate of his was Oliver Cromwell, who later gained prominence as the Lord Protector of England.[20] After college, Wheelwright was ordained a deacon and then a priest of the Anglican Communion.[19] He first married Mary Storre, the daughter of Thomas Storre who was the vicar of Bilsby;[21] he became the Bilsby vicar himself upon the death of his father-in-law in 1623 and held that position for ten years. His wife died in 1629 and was buried in Bilsby on 18 May,[21] shortly after which he married Mary Hutchinson. Mary was the daughter of Edward Hutchinson of Alford, and a sister of William Hutchinson, Anne Hutchinson's husband.[19]

In 1633, Wheelwright was suspended from his position at Bilsby.[22] His successor was chosen in January 1633, when Wheelwright tried to sell his Bilsby ministry back to its patron to get funds to travel to New England. Instead of procuring the necessary funds, he was convicted of simony (selling church offices).[23] He next preached for a short while at Belleau, Lincolnshire but was soon silenced for his Puritan opinions, and he continued making plans for his emigration from England.[19] Like John Cotton, Wheelwright preached a message of "free grace," rejecting the notion that a man's salvation was demonstrated through his works.[24] He embarked for New England in early spring 1636, where he was warmly received in Boston.[25]

John Cotton

The third person who was deeply complicit in the controversy was John Cotton, a minister whose theological views differed from those of other ministers in New England. He suffered in attempting to remain supportive of his follower Hutchinson, while also maintaining a conciliatory stance towards his ministerial colleagues.[26]

In 1612, Cotton left a tutoring position at Emmanuel College, Cambridge and became the minister at Saint Botolph's Church in Boston, Lincolnshire.[11][27] He was only 27 years old, yet he was considered one of the leading Puritans in England due to his learned and vigorous preaching.[11] His theology was influenced by English Puritan Richard Sibbes, but his basic tenets were from John Calvin. At one point he wrote, "I have read the fathers, and the schoolmen and Calvin too, but I find that he that has Calvin has them all."[28]

By 1633, Cotton's inclination toward Puritan practices had attracted the attention of William Laud, who was on a mission to suppress any preaching and practices that did not conform to the tenets of the established Anglican Church.[29] In that year, Cotton was removed from his ministry, threatened with imprisonment, and forced into hiding.[29] He made a hasty departure for New England aboard the Griffin, taking his pregnant wife. She was so close to term that she bore her child aboard the ship, and they named him Seaborn.[30]

On his arrival in September 1633, Cotton was openly welcomed, having been personally invited to the colony by Governor Winthrop.[30] Once established in Boston, his enthusiastic evangelism brought about a religious awakening in the colony, and there were more conversions during his first six months in the pastorate than there had been the previous year.[31]

Henry Vane

Henry Vane was a young aristocrat, and possibly the most socially prominent person to come to the Massachusetts Bay colony in the 1630s.[6] He was born in 1613 to Henry Vane the Elder, a Privy counsellor of Charles I and therefore one of the most powerful men in England.[32] The younger Vane had an intense religious experience when he was in his teens which left him confident of his salvation, and his ensuing beliefs did not conform with the established Anglican Church.[32] He came to New England with the blessing of William Laud, who thought that it would be a good place for him to get Puritanism out of his system.[32] He was 22 years old when he arrived in Boston on 6 October 1635, and his devoutness, social rank, and character lent him an air of greatness. Winthrop called him a "noble gentleman" in his journal.[32]

Vane became a member of the Boston church on 1 November 1635 and was given the honor of sitting on the magistrate's bench in the meetinghouse, next to Winthrop. In January 1636, he took it upon himself to arbitrate in a dispute between Winthrop and magistrate Thomas Dudley, and he was elected governor of the colony in May, despite his youth and inexperience.[32] He built an extension to Cotton's house in which he lived while in New England, and was "deeply taken with the radical possibilities in Cotton's theology."[33] Historian Michael Winship states that it was Vane who encouraged Hutchinson to set up her own conventicles and to actively engage in her own theological radicalism.[33] He writes that Vane had an appetite for unconventional theological speculation, and that it was "this appetite that profoundly altered the spiritual dynamic in Massachusetts". Vane's enthusiasm caused Cotton "to make his first serious stumble", according to Winship, and it "pushed Anne Hutchinson into the public limelight".[32] Vane's role is almost entirely neglected by scholars, but Winship surmises that he may have been the most important reason that the controversy reached a high pitch.[33]

Events

The Antinomian Controversy began with some meetings of the Massachusetts colony's ministers in October 1636 and lasted for 17 months, ending with the church trial of Anne Hutchinson in March 1638.[34] However, there were signs of its emergence well before 1636, and its effects lasted for more than a century afterward. The first hints of religious tension occurred in late summer 1634 aboard the ship Griffin, when Anne Hutchinson was making the voyage from England to New England with her husband and 10 of her 11 living children. The Reverend Zechariah Symmes preached to the passengers aboard the ship and, after the sermons, Hutchinson asked him pointed questions about free grace.[35] In England, Hutchinson had criticized certain clergymen who were esteemed by Symmes, and her questioning caused him to doubt her orthodoxy.[35] Anne's husband was accepted readily into the Boston church congregation, but her membership was delayed a week because of Symmes' concerns about her religious orthodoxy.

By the spring of 1636, John Cotton had become the focus of the other clergymen in the colony.[36] Thomas Shepard was the minister of Newtown, later renamed Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he wrote a letter to Cotton and warned him of the strange opinions being circulated among his Boston parishioners. Shepard also expressed concern about Cotton's preaching and some of the points of his theology.[37]

Meetings of the ministers

In October 1636, the ministers confronted the question of religious opinions and had a "conference in private" with Cotton, Hutchinson, and Wheelwright.[36] Some of the ministers had heard that Hutchinson considered them to be unable ministers of the New Testament. In private, she essentially agreed that this was her opinion, and that she thought that only Cotton preached with the "seal of the Spirit". Despite these private antipathies, the outcome of the meeting was favorable and the parties were largely in agreement. Cotton gave satisfaction to the other ministers that good works (termed "sanctification" by the Puritans) did provide one outward demonstration of inward grace, and Wheelwright agreed as well.[36] However, the effects of the conference were short-lived because a majority of the members of the Boston church were in accord with Hutchinson's "free grace" ideas, and they wanted Wheelwright to become the church's second pastor with Cotton. The church already had pastor John Wilson, who was unsympathetic to Hutchinson. Wilson was a friend of John Winthrop, who was a layman in the church. Winthrop took advantage of a rule requiring unanimity in a church vote, and was thus able to thwart the appointment of Wheelwright.[36] Wheelwright instead was allowed to preach at Mount Wollaston, considered to be a part of Boston but about ten miles south of the Boston church.[38]

In December 1636, the ministers met once again, but this meeting did not produce agreement. Cotton argued that the question of outward manifestations of salvation was essentially a "covenant of works".[39] These theological differences had begun to take their toll in the political aspects of the colony, and Massachusetts governor Henry Vane (a strong admirer of Hutchinson) announced his resignation to a special session of the deputies.[39] His reasoning was that God's judgment would "come upon us for these differences and dissensions".[39] The members of the Boston church induced Vane to withdraw his resignation, while the General Court began to debate who was responsible for the colony's troubles.[39] The General Court was deeply divided, like the remainder of the colony, and called for a general fast to take place on 19 January in hopes that such repentance would restore peace.[39]

Wheelwright's fast-day sermon

Wheelwright was attending services at the Boston church during the appointed January day of fasting, and he was invited to preach during the afternoon.[39] His sermon may have seemed benign to the average listener in the congregation, but most of the colony's ministers found it to be censurable. Instead of bringing peace, the sermon fanned the flames of controversy and, in Winthrop's words, Wheelwright "inveighed against all that walked in a covenant of works, as he described it to be, viz., such as maintain sanctification [holiness of behavior] as an evidence of justification etc. and called them antichrists, and stirred up the people against them with much bitterness and vehemency."[39] The followers of Hutchinson were encouraged by the sermon and intensified their crusade against the "legalists" among the clergy. During church services and lectures, they publicly asked the ministers about their doctrines which disagreed with their own beliefs.[39]

The General Court met on 9 March, and Wheelwright was called upon to answer for his sermon.[40] He was judged guilty of contempt and sedition for having "purposely set himself to kindle and increase" bitterness within the colony.[40] The vote did not pass without a fight, and Wheelwright's friends protested formally. The Boston church favored Wheelwright in the conflict and "tendered a petition in his behalf, justifying Mr. Wheelwright's sermon", with 60 people signing this remonstrance protesting the conviction.[41]

Election of May 1637

The Court rejected all of the protests concerning Wheelwright. Governor Vane attempted to stop the Court from holding its next session in Newtown, where he feared that the orthodox party stood a better chance of winning than in Boston, but he was overruled.[40] In his journal, Winthrop recorded the excitement and tension of election day on 17 May. Vane wanted to read a petition in defense of Wheelwright, but the Winthrop party insisted that the elections take place first, and then the petitions could be heard.[40] After some debate, the majority of freemen wanted to proceed with the election, and they finally elected Winthrop as governor in place of Vane. When the magistrates were elected, those who supported Wheelwright had been voted out of office.[42]

The Court also passed a law that no strangers could be received within the colony for longer than three weeks without the Court's permission. According to the opinion one modern writer, Winthrop saw this as a necessary step to prevent new immigrants from being added to the Antinomian faction.[42] This new law was soon tested when William Hutchinson's brother Samuel arrived with some friends from England. They were refused the privilege of settling in the Bay Colony, despite Vane's protests concerning Winthrop's alien act. Vane had had enough, and he boarded a ship on 3 August and departed New England, never to return.[43] Nevertheless, he maintained his close ties with the colonies, and several years later even Winthrop called him "a true friend of New England."[44]

Synod of 1637

The controversy continued to heat up and the ministers convened a synod in Newtown on 30 August in hopes of resolving some of the theological disputes. An important item on the agenda was to identify and refute the errors of the Antinomians, a list of 90 items, though many of them were repetitious. The other major task was to confront the various problems of church order that had been exposed during the controversy.[42] After three weeks, the ministers felt that they had better control of church doctrines and church order, allowing the synod to adjourn on 22 September.[42]

The ministers had found agreement, but the free grace advocates continued their teachings, causing a state of dissension to be widespread throughout the colony, and Winthrop realized that "two so opposite parties could not contain in the same body, without apparent hazard of ruin to the whole."[42] The elections of October 1637 brought about a large turn-over of the deputies to the General Court. Only 17 of the 32 deputies were re-elected, as changes were deemed necessary in many of the colony's towns.[45] Boston continued to be represented with strong Free Grace advocates; two of its three deputies (William Aspinwall and William Coddington) continued in their previous roles, while John Coggeshall was newly elected. The deputies from most of the other towns were opposed to the Free Grace supporters.[46]

November 1637 court

The next session of the General Court began on 2 November 1637 at the meeting house on Spring Street in Newtown.[47] The first business of the court was to examine the credentials of its members; Aspinwall was called forward and identified as one of the signers of the petition in favor of Wheelwright. He was dismissed from the court by a motion and show of hands. This brought a strong reaction from Coggeshall, a deacon of the Boston church and deputy, and he too was ejected from the court by a show of hands.[48] Bostonians were resentful of Winthrop's overbearing manner but were willing to replace the two dismissed deputies with William Colburn and John Oliver, both supporters of Hutchinson and Wheelwright, as were the other Bostonians eligible for the post.[49]

One of the first orders of business on that Monday was to deal with Wheelwright, whose case had been long deferred by Winthrop in hopes that he might finally see the error of his ways.[49] Wheelwright stood firm, denying any guilt of the charges against him, and asserting that he "had delivered nothing but the truth of Christ."[49] Winthrop painted a picture of a peaceful colony before Wheelwright's arrival, and showed that things had degenerated after his fast-day sermon: Boston had refused to join the Pequot War, Pastor Wilson was often slighted, and controversy arose in town meetings.[50] Wheelwright was steadfast in his demeanor but was not sentenced as the court adjourned for the evening.[50]

John Oliver was identified on Tuesday, the second day of the proceedings, as a signer of the petition in support of Wheelwright, and was thus not seated at the court, leaving Boston with only two deputies.[51] After further argument in the case of Wheelwright, the court declared him guilty of troubling the civil peace, of holding corrupt and dangerous opinions, and of contemptuous behavior toward the magistrates. He was sentenced to be disfranchised and banished from the colony, and was given two weeks to depart the jurisdiction.[52]

Coggeshall was next to be called forth, and he was charged with a variety of miscarriages "as one that had a principall hand in all our late disturbances of our publike peace."[53] The court was divided on the punishment for the magistrate and opted for disfranchisement over banishment.[54] Then Aspinwall, the other dismissed Boston deputy, was called forth for signing the petition in favor of Wheelwright and for authoring it, as well. Unlike the more submissive Coggeshall, Aspinwall was defiant and the court sentenced him to banishment because of his contemptuous behavior.[53] With these lesser issues put aside, it was now time for the court to deal with the "breeder and nourisher of all these distempers," as Emery Battis puts it, and Hutchinson was called.[55]

Trial of Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson had not participated in the political protests of her free grace allies, and the court could only charge her with "countenancing" those who did.[56] Additional accusations made against her concerned her weekly meetings at her house and the statements that she made against the ministers for preaching what she called a "covenant of works".[56]

Governor Winthrop served as both the primary prosecutor and judge at the trial. The other magistrates representing the prosecution were Deputy Governor Thomas Dudley, John Endecott, Richard Bellingham, Israel Stoughton, Roger Harlakenden, Increase Nowell, Simon Bradstreet, and John Humphrey.[57] There were eight ministers present for the proceedings, beginning with John Cotton and John Wilson from the church at Boston.[58] Hugh Peter came all the way from Salem, and Thomas Weld was there from Roxbury as one of Hutchinson's accusers. With him was his colleague John Eliot who was opposed to the doctrines of Hutchinson.[58] George Phillips came from Watertown, Zechariah Symmes from Charlestown, and Thomas Shepard from the home church in Newtown, where the court was being held.[58]

Winthrop questioned Hutchinson heavily on her association with those who had caused trouble in the colony, and on the meetings that she held at her house, but Hutchinson effectively stonewalled this prosecutorial thrust by answering questions with questions and matching scripture with scripture.[59] Dudley then stepped in and confronted her concerning having men at her home meetings and "traducing [slandering] the ministers" by saying that they "preached a covenant of works, and only Mr. Cotton a covenant of grace."[60] To the latter charge Dudley added, "you said they were not able ministers of the new testament, but Mr. Cotton only!"[61] This last assertion brought pause to Hutchinson, who knew what she had said and to whom she had said it. According to the modern interpretations of Emery Battis, she had assumed that her statements would be confidential and private when she made them during the meetings with the ministers in October 1636.[61]

She said, "It is one thing for me to come before a public magistracy and there to speak what they would have me speak and another when a man comes to me in a way of friendship privately."[61] Hutchinson's defense was that she had spoken only reluctantly and in private, and that she "must either speak false or true in my answers" in the ministerial context of the meeting.[62] The court, however, did not make any distinction between public and private statements.[62]

During the morning of the second day of the trial, Hutchinson continued to accuse the ministers of violating their mandate of confidentiality and of deceiving the court about her reluctance to share her thoughts with them. She now insisted that the ministers testify under oath.[62] As a matter of due process, the ministers had to be sworn in, but would agree to do so only if the defense witnesses spoke first. There were three defense witnesses, all from the Boston church: deacon John Coggeshall, lay leader Thomas Leverett, and minister John Cotton.[63] The first two witnesses made brief statements that had little effect on the court. When Cotton testified, he said that he did not remember many events of the October meeting, and he attempted to soften the meanings of Hutchinson's statements. He also stated that the ministers did not appear to be as upset by Hutchinson's remarks at the October meeting as they appeared to be later.[64] Dudley reiterated that Hutchinson had told the ministers that they were not able ministers of the New Testament, and Cotton replied that he did not remember her saying that.[64]

There was more parrying between Cotton and the court, but the exchanges were not recorded in the transcript of the proceedings. Hutchinson next asked the court for leave to "give you the ground of what I know to be true."[65] She then addressed the court with her own judgment, becoming both didactic and prophetic and claiming her source of knowledge to be direct, personal revelation from God.[56] She ended her statement by prophesying, "if you go on in this course [in which] you begin, you will bring a curse upon you and your posterity, and the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it."[66] "The judges were aghast," historian Emery Battis writes. "She had defied the Court and threatened the commonwealth with God's curse."[66] Cotton attempted to defend her but was challenged by the magistrates, until Winthrop ended the questioning.[67] A vote was taken on a sentence of banishment, only the only dissenters were the two remaining deputies from Boston, Colburn and Coddington. Winthrop then read the order: "Mrs. Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society, and are to be imprisoned till the court shall send you away."[68]

After the trial

Within a week of Hutchinson's sentencing, some of her supporters were called into court and were disfranchised but not banished. The constables were then sent from door to door throughout the colony's towns to disarm those who signed the Wheelwright petition.[69] Within ten days, these individuals were ordered to deliver "all such guns, pistols, swords, powder, shot, & match as they shall be owners of, or have in their custody, upon paine of ten pound[s] for every default".[69] A great number recanted and "acknowledged their error" in signing the petition when they were faced with the confiscation of their firearms. Those who refused to recant suffered hardships and, in many cases, decided to leave the colony.[70] In Roxbury, Philip Sherman, Henry Bull, and Thomas Wilson were excommunicated from the church, and all three left the colony.[71]

Following her civil trial, Hutchinson needed also to face a trial by the clergy, and this could not take place until the following March. In the interim, she was not allowed to return home, but instead was detained at the house of Joseph Weld, brother of the Reverend Thomas Weld, which was located in Roxbury, about two miles from her home in Boston.[72] The distance was not great, yet she was rarely able to see her children because of the winter weather, which was particularly harsh that year.[73] She was frequently visited by the various ministers; modern writer Eve LaPlante claims that they came with the intention of reforming her thinking and also to collect evidence to use against her in the forthcoming church trial. LaPlante also claims that Winthrop was determined to keep her isolated so that others would not be inspired by her.[73]

The ordeal was difficult for John Cotton. He decided to leave Massachusetts and go with the settlers to New Haven, not wanting to "breed any further offensive agitation". This proposal was very unwelcome to the magistrates, who viewed such a departure as tarnishing to the reputation of the colony.[74] Cotton was persuaded to remain in Boston, though he continued to be questioned for his doctrines. His dilemma was like that of Wheelwright, but the difference between the two men was not in their doctrines but in their personalities. Wheelwright was contentious and outspoken, while Cotton was mild and tractable.[75] It was Wheelwright's nature to separate from those who disdained him; it was Cotton's nature to make peace without compromising his essential principles, according to the views of some modern historians.[75]

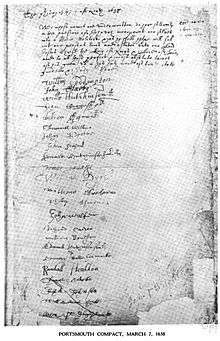

Former Boston magistrate and Hutchinson supporter William Coddington was not happy about the trials, and he began making plans for his own future in consultation with others affected by the Court's decisions. He remained on good terms with Winthrop and consulted with him about the possibility of leaving the colony in peace.[76] Winthrop was encouraging and helped to smooth the way with the other magistrates. The men were uncertain where to go; they contacted Roger Williams who suggested that they purchase land of the Indians along the Narraganset Bay, near his settlement at Providence Plantation. On 7 March 1638, a group of men gathered at the home of Coddington and drafted a compact.[77] Several of the strongest supporters of Hutchinson and Wheelwright signed the document, having been disfranchised, disarmed, or excommunicated, including John Coggeshall, William Aspinwall, John Porter, Philip Sherman, Henry Bull, and several members of the Hutchinson family. Some who were not directly involved in the events also asked to be included, such as Randall Holden and physician and theologian John Clarke.[77]

Hutchinson's church trial

Hutchinson was called to her church trial on Thursday, 15 March 1638 following a four-month detention in Roxbury, weary and in poor health. The trial took place at her home church in Boston, though many of her supporters were either gone or compelled to silence. Her husband and other friends had already left the colony to prepare for a new place to live. The only family members present were her oldest son Edward with his wife, her daughter Faith with her husband Thomas Savage, and her much younger sister Katharine with her husband Richard Scott.[78] The complement of ministers was largely the same as it had been during her civil trial, though the Reverend Peter Bulkley from Concord took part, as did the newly arrived Reverend John Davenport who was staying with John Cotton and preparing to begin a new settlement at New Haven.

The ministers were all on hand, and ruling elder Thomas Leverett was charged with managing the examination. He called Mrs. Hutchinson and read the numerous "errors" with which she had been charged. What followed was a nine-hour interrogation where only four of the many were covered. At the end, Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of delivering the admonition to his admirer. He said, "I would speake it to Gods Glory [that] you have bine an Instrument of doing some good amongst us... he hath given you a sharp apprehension, a ready utterance and abilitie to exprese yourselfe in the Cause of God."[79] With this said, it was the overwhelming conclusion of the ministers that Hutchinson's beliefs were unsound and outweighed any good that she had done, and that she endangered the spiritual welfare of the community.[79] Cotton continued, "You cannot Evade the Argument... that filthie Sinne of the Communitie of Woemen; and all promiscuous and filthie cominge togeather of men and Woemen without Distinction or Relation of Mariage, will necessarily follow.... Though I have not herd, nayther do I thinke you have bine unfaythfull to your Husband in his Marriage Covenant, yet that will follow upon it."[79] He concluded, "Therefor, I doe Admonish you, and alsoe charge you in the name of Ch[rist] Je[sus], in whose place I stand... that you would sadly consider the just hand of God agaynst you, the great hurt you have done to the Churches, the great Dishonour you have brought to Je[sus] Ch[rist], and the Evell that you have done to many a poore soule."[80] With this, Hutchinson was instructed to return on the next lecture day in one week.[80]

With the permission of the court, Hutchinson was allowed to spend the week at the home of Cotton, where Reverend Davenport was also staying. All week, the two ministers worked with her, and under their supervision she had written out a formal recantation of her opinions that brought objection from all the ministers.[81] She stood at the next meeting, on Thursday, 22 March and read her recantation to the congregation. Following more accusations, the proposal was made for excommunication, and the silence of the congregation allowed it to proceed. Wilson delivered the final address, "Forasmuch as you, Mrs. Hutchinson, have highly transgressed and offended... and troubled the Church with your Errors and have drawen away many a poor soule, and have upheld your Revelations; and forasmuch as you have made a Lye... Therefor in the name of our Lord Je[sus] Ch[rist]... I doe cast you out and... deliver you up to Sathan... and account you from this time forth to be a Hethen and a Publican... I command you in the name of Ch[rist] Je[sus] and of this Church as a Leper to withdraw your selfe out of the Congregation." [82]

Hutchinson's friend Mary Dyer put her arm in Anne's and walked out with her. A man by the door said, "The Lord sanctifie this unto you," to which Hutchinson replied, "Better to be cast out of the Church than to deny Christ."[83]

The controversy came to an abrupt end with Anne Hutchinson's departure.

Hutchinson's fate

Hutchinson, her children, and others accompanying her all traveled for more than six days by foot in the April snow to get from Boston to Roger Williams' settlement at Providence Plantation.[84] They then took boats to get to Rhode Island (as it was then called) in the Narragansett Bay, where several men had gone ahead of them to begin constructing houses.[85] In the second week of April, she reunited with her husband, from whom she had been separated for nearly six months.[85] During the strife of building the new settlement, Anne's husband William Hutchinson briefly became the chief magistrate (judge) of Portsmouth, but he died at the age of 55 some time after June 1641, the same age at which Anne's father had died.[86][87]

Following the death of her husband, Anne Hutchinson felt compelled to move totally out of the reach of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its sister colonies in Connecticut and New Haven into the jurisdiction of the Dutch.[88] Some time after the summer of 1642, she went to New Netherland along with seven of her children, a son-in-law, and several servants—16 total persons by several accounts. They settled near an ancient landmark called Split Rock, not far from what became the Hutchinson River in northern Bronx, New York City.[88]

The timing was unfortunate for the Hutchinsons' settlement in this area. Animosity had grown between the Dutch and the Siwanoy Indians of New Netherland. Hutchinson had a favorable relationship with the Narragansetts in Rhode Island, and she might have felt a false sense of safety among the Siwanoys.[88] However, these Indians rampaged through the New Netherland colony in a series of incidents known as Kieft's War, and a group of warriors entered the small settlement above Pelham Bay in late August 1643 and killed every member of the Hutchinson household, except for Hutchinson's nine-year-old daughter Susanna.[89]

Susanna returned to Boston, married, and had many children. Four of Hutchinson's 14 other children are known to have survived and had offspring. Three United States presidents descend from her.[90]

Wheelwright, Cotton, and Vane

Wheelwright crossed the frozen Merrimack River with a group of followers after he was banished from the Massachusetts colony and established the town of Exeter, New Hampshire. After a few years there, he was forced to leave, as Massachusetts began to expand its territorial claims. He went from there to Wells, Maine for several years, and then accepted the pastorate in Hampton, which was in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1644, Winthrop's account of the events from 1636 to 1638 was published in London under the title A Short Story of the Rise, reign, and ruine of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines, which is often simply called the Short Story. In response to this, supporters of Wheelwright wrote Mercurius Americanus which was published in London the following year, giving his views of the events.[91]

From Hampton, Wheelwright returned to England with his family in 1655, staying for more than six years, at times as the guest of Henry Vane. In 1662, he returned to New England and became the pastor of the church at Salisbury, Massachusetts, having his banishment sentence revoked in 1644 and receiving a vindication in 1654. He died in Salisbury in 1679.[19]

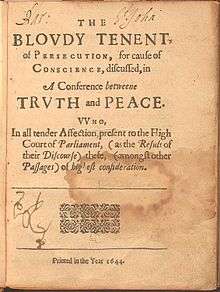

Cotton continued as the minister of the church in Boston until his death in 1652. He wrote two major works following the Antinomian Controversy: The Keyes of the Kingdom of Heaven (1644) and The Way of Congregational Churches Cleared (1648).[92] The latter work was in response to Robert Baillie's A Dissuasive against the Errours of the Time published in 1645. Baillie was a Presbyterian minister who was critical of Congregationalism, specifically targeting Cotton in his writings.[93] Cotton also fought a pamphlet war with Roger Williams. Williams published The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience in 1644, and Cotton answered with The Bloudy Tenent washed and made white in the bloud of the Lamb, after which Williams responded with yet another pamphlet.[94]

Vane departed the Massachusetts colony in October 1637 and became the Treasurer of the Royal Navy in England within two years. During the First English Civil War, he took on a leadership role in Parliament, and soon thereafter worked closely with Oliver Cromwell. Vane was opposed to the trial of Charles I, but he was appointed to the English Council of State after the king's execution in 1649, the new executive authority for the Kingdom of England. A fallout between Parliament and the Army ended his cordial relationship with Cromwell, whose role as Lord Protector began in 1653. Vane was invited to sit on Cromwell's council but refused, effectively putting himself into retirement where he wrote several works. Following the restoration of the monarchy in England in 1660, he was imprisoned for his role during the interregnum and then executed in 1662 at Tower Hill.[95][96]

Historical impact

Modern historian David Hall views the events of 1636 to 1638 as being important to an understanding of religion, society, and gender in early American history.[9] Historian Charles Adams writes, "It is no exaggeration now to say that in the early story of New England subsequent to the settlement of Boston, there was in truth no episode more characteristic, more interesting, or more far-reaching in its consequences, than the so-called Antinomian controversy."[97] It came at a time when the new society was still taking shape and had a decisive effect upon the future of New England.[98]

The controversy had an international effect, in that Puritans in England followed the events closely. According to Hall, the English were looking for ways to combat the Antinomians who appeared after the Puritan Revolution began in 1640.[93] In Hall's view, the English Congregationalists used the controversy to demonstrate that Congregationalism was the best path for religion, whereas the Presbyterians used the controversy to demonstrate the exact opposite.[93] Presbyterian writer Robert Baillie, a minister in the Church of Scotland, used the controversy to criticize colonial Congregationalism, particularly targeting John Cotton.[99] The long-term effect of the Antinomian controversy was that it committed Massachusetts to a policy of strict religious conformity.[100] In 1894 Adams wrote, "Its historical significance was not seriously shaken until 1819 when the Unitarian movement under Channing brought about results to Calvinistic theology similar to those which the theories of Darwin worked on the Mosaic account of the origin of man."[100]

Published works

The events of the Antinomian Controversy have been recorded by numerous authors over a period of nearly 375 years. Following is a summary of some of the most significant published works relating to the controversy, most of which were listed by Charles Francis Adams, Jr. in his 1894 compilation of source documents on the controversy.[101] In addition to these sources, there have been many biographies written about Anne Hutchinson during the 20th and 21st centuries.

The first account of the controversy was A Short Story of the Rise, reign, and ruine of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines (usually shortened to Short Story) written by John Winthrop in 1638, the year after Hutchinson had been given the order of banishment and the year of her departure from the Bay colony. The work includes an incomplete transcript of the trial of Hutchinson. It was rushed to England in March or April 1638, but was not published until 1644.[102] As it was prepared for publication, Reverend Thomas Weld added a preface, calling the story "newly come forth in the Presse" even though it had been written six years earlier.[103]

The Short Story was highly critical of Anne Hutchinson and John Wheelwright, and Wheelwright felt compelled to present his side of the story once it was published in England, as his son was going to school in England at the time. Mercurius Americanus was published in London in 1645 under the name of John Wheelwright, Jr. to clear Wheelwright's name.[104] Thomas Hutchinson was a descendant of Anne Hutchinson and loyalist governor of Massachusetts, and he published the History of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1767 which includes the most complete extant transcript of Hutchinson's trial. This transcript is found in the compilations of both Adams and Hall.[105][106]

The Life of Sir Henry Vane by Charles W. Upham was published in 1835 and later published in Jared Sparks' Library of American Biography, vol. IV.[107] George E. Ellis published The Life of Anne Hutchinson in 1845[108] which is likely the first biography of Hutchinson. Many biographies of both of these individuals appeared in the 20th century. In 1858, John G. Palfrey devoted a chapter of his History of New England to the controversy,[109] and John A. Vinton published a series of four articles in the Congregational Quarterly in 1873 that were supportive of Winthrop's handling of the controversy.[101] In 1876, Charles H. Bell published the only biography of John Wheelwright, and it includes transcripts of Wheelwright's Fast Day Sermon as well as Mercurius Americanus (1645). The first major collection of source documents on the controversy was Antinomianism in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, published by Charles Adams in 1894.

The next major study on the controversy emerged in 1962 when Emery Battis published Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This sociological and psychological study of the controversy and its players provides many details about the individuals, trials, and other events of the controversy.[110] David Hall added to Adams' collection of source documents in The Antinomian Controversy (1968) and then updated the work with additional documents in 1990.[111] Two books on the controversy were written by Michael P. Winship: Making Heretics (2002) and The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson (2005).

Supporters and followers of Hutchinson and Wheelwright

Emery Battis presents a sociological perspective of the controversy in Saints and Sectaries (1962) in which he asks why so many prominent people were willing to give up their homes to follow Hutchinson and Wheelwright out of the Massachusetts colony. He compiles a list of all members of the Massachusetts Bay Colony who were connected to the Antinomian controversy and breaks them into three groups based on the strength of their support for Hutchinson and Wheelwright: the Core Group, the Support Group, and the Peripheral Group.[112] He collected statistics on the members of each group, some of which are shown in the following tables.

The place of origin of the individual is the English county from which he came, the year of arrival is the sailing year from England to New England, and the residence is the New England town where the person lived during the controversy. The disposition was the action taken against the person by the Massachusetts court. Many individuals were disarmed, meaning that they were ordered to turn in all of their weapons to the authorities. To be disfranchised meant to lose the ability to vote. Being dismissed meant being removed from the church but allowed to establish membership elsewhere; to be excommunicated meant being totally disowned by the church and removed from fellowship with believers. Banishment meant being ordered to leave the jurisdiction of the colony. Most of those who were banished went either north to Exeter or Dover (New Hampshire) or south to Portsmouth, Newport, or Providence (Rhode Island). At least two individuals went back to England.[112]

Core group

This group included the strongest supporters of Hutchinson and Wheelwright. The most serious action was taken against them; all of them left the Massachusetts Bay Colony, though several of them recanted and returned.[113] Most of these men signed the petition in favor of Wheelwright and were thus disarmed. Several of these individuals signed the Portsmouth Compact, establishing a government on Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island), and some became presidents, governors, or other leaders in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

| Core group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Place of origin | Year of arrival | Residence | Vocation | Disposition | Went to | Comments |

| William Alford | London | 1634 | Salem | Skinner, merchant[114] | Disarmed | Portsmouth, but returned | |

| William Aspinwall | 1630 | Boston | Notary, court recorder[115] | Disarmed Disfranchised |

Portsmouth, but returned | Signed Portsmouth Compact | |

| William Baulston | 1630 | Boston | Innkeeper | Disarmed Disfranchised Banished |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact | |

| William Brenton | 1633[116] | Boston | Merchant | Portsmouth | |||

| Richard Bulgar | 1630 | Boston | Bricklayer | Disarmed | Exeter, but returned | ||

| Henry Bull | 1635 | Roxbury, Boston[117] | Servant | Disarmed Disfranchised Excommunicated |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact Became a Quaker | |

| Richard Carder | before 1636 | Boston | Disarmed Banished |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact Follower of Gorton | ||

| William Coddington | Lincolnshire | 1630 | Boston | Merchant, magistrate[118] | Banished | Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact Became a Quaker |

| John Coggeshall | Essex | 1632 | Boston | Silk mercer, merchant[118] | Disarmed Disfranchised Banished |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact |

| John Compton | 1634[119] | Roxbury, Boston[119] | Laborer, clothier[119] | Disarmed | |||

| Richard Dummer | Hampshire | 1632 | Newbury | Miller[120] | Disarmed | Portsmouth, but returned | |

| William Dyer | Lincolnshire, London | before 1635 | Boston | Milliner | Disarmed Disfranchised |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact; his wife, Mary Dyer, became a noted Quaker martyr |

| Nicholas Easton | Hampshire | 1634 | Newbury | Tanner | Disarmed Banished |

Portsmouth | Became a Quaker |

| Henry Elkins | before 1634 | Boston | Tailor | Disarmed Dismissed |

Exeter | ||

| William Foster | 1634 | Ipswich | Shipmaster | Disarmed Banished |

Newport[121] | ||

| William Freeborn | Essex | 1634 | Roxbury, Boston[122] | Miller[122] | Disarmed Banished |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact Became a Quaker |

| Isaac Grosse | Norfolk[123] | before 1635 | Boston | Brewer, husbandman[123] | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

Exeter, but returned | |

| Robert Harding | 1630 | Boston | Mercer and merchant[124] | Wife admonished by church | Portsmouth, but returned | ||

| Richard Hawkins | Huntingdon | before 1636 | Boston | Wife (Jane) banished | Portsmouth | Wife was a familist | |

| Edward Hutchinson, Sr. | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Boston | Baker[125] | Disarmed Disfranchised Banished |

Portsmouth | Brother of William Hutchinson Signed Portsmouth Compact |

| Edward Hutchinson, Jr. | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Boston | Mercer | Portsmouth | Son of William and Anne Hutchinson Signed Portsmouth Compact | |

| Francis Hutchinson | Lincolnshire | 1634 | Boston | Banished in 1641 | Portsmouth | Son of William and Anne Hutchinson | |

| Richard Hutchinson | Lincolnshire | 1634 | Boston | Linen draper | Disarmed | London, not to return | Son of William and Anne Hutchinson |

| William Hutchinson | Lincolnshire | 1634 | Boston | Mercer | Wife banished and excommunicated |

Portsmouth | Husband of Anne Hutchinson Signed Portsmouth Compact |

| Richard Morris | The Hague, Holland[126] | 1630 | Roxbury | Soldier[126] | Disarmed | Exeter | |

| John Porter | 1633[127] | Roxbury and Boston[127] | Disarmed Banished |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact | ||

| Robert Potter | 1634[128] | Roxbury | Banished Excommunicated |

Portsmouth | Follower of Gorton | ||

| John Sanford | 1631[129] | Boston | Cannoneer[129] | Disarmed | Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact | |

| Thomas Savage | Somerset? | 1635 | Boston | Tailor | Disarmed, but acknowledged error | apparently never left Boston[130] | Son-in-law of Anne Hutchinson Signed Portsmouth Compact |

| Philip Sherman | Essex | 1633 | Roxbury | Disarmed Excommunicated |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact | |

| John Spencer | Surrey | 1634[131] | Newbury | Magistrate[131] | Disarmed Discharged from position as captain |

returned to England[131] | |

| John Underhill | Warwickshire, Holland[132] | 1630 | Boston | Soldier[132] | Disarmed Banished |

Exeter[132] | |

| Henry Vane | London | 1635 | Boston | Gentleman | England, not to return | Governor of colony | |

| John Walker | 1633[133] | Roxbury | Disarmed | Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact | ||

| Thomas Wardell | Lincolnshire | 1634[134] | Boston | Shoemaker | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

Exeter, but returned | |

| William Wardell | Lincolnshire | 1633[135] | Boston | Tavern keeper[135] | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

Exeter[135] | |

| John Wheelwright | Lincolnshire | 1636 | Boston Mount Wollaston |

Clergyman | Disfranchised Banished |

Exeter | Banishment revoked in 1644; preached in Salisbury |

| Samuel Wilbore | Essex | 1633[136] | Boston | Merchant | Disarmed Banished Recanted in 1639 |

Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact |

Support group

This group consists of individuals who signed the petition supporting Wheelwright and were thus disarmed, but who were not willing to leave the Massachusetts Colony. When action was taken against them, they largely recanted or endured the punishment, and only a few of them left Massachusetts.[137]

| Support group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Place of origin | Year of arrival | Residence | Vocation | Disposition | Went to | Comments |

| William Baker | before 1633 | Charlestown | Husbandry | Acknowledged error | |||

| Edward Bates | before 1633 | Boston | Servant | Disarmed | |||

| Edward Bendall | Surrey | 1630 | Boston | Dockman | Disarmed | ||

| John Biggs | Suffolk | 1630 | Boston | Acknowledged error | |||

| Zaccheus Bosworth | Northamptonshire | 1630 | Boston | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| George Bunker | Bedfordshire | before 1634 | Charlestown | Husbandry | Disarmed | ||

| George Burden | Gloucestershire | 1635 | Boston | Shoemaker | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| John Button | before 1633 | Boston | Miller | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Edward Carrington | 1632 | Charlestown | Turner | Acknowledged error | |||

| John Clarke | Suffolk | 1637 | Boston | Physician | Disarmed[138] | Portsmouth | Signed Portsmouth Compact Became a Baptist minister |

| Samuel Cole | 1630 | Boston | Innkeeper Confectioner |

Disarmed Acknowledged error |

Father-in-law of Susanna Cole | ||

| William Commins | before 1636 | Salem | Disarmed | ||||

| Richard Cooke | before 1634 | Boston | Tailor | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| John Davy | 1635 | Boston | Joiner | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Edward Denison | Hertfordshire | 1630 | Roxbury | Disarmed | |||

| William Denison | Hertfordshire | 1630 | Roxbury | Merchant | Disarmed | ||

| William Dinely | Lincolnshire | before 1635 | Boston | Barber-surgeon | Disarmed Disfranchised Acknowledged error |

||

| Jacob Eliot | Essex | 1630 | Boston | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Thomas Ewar | Kent | 1635 | Charlestown | Tailor | Acknowledged error | ||

| Richard Fairbank | before 1633 | Boston | Shopkeeper | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Mathias Faunce | Essex? | 1623? | Plymouth? | Acknowledged error | |||

| Henry Flint | Derbyshire | before 1636 | Boston Mount Wollaston |

Clergyman | Acknowledged error | ||

| William Frothingham | Yorkshire | 1630 | Charlestown | Husbandry | Acknowledged error | ||

| Stephen Greensmith | before 1636 | Boston | Merchant | Fined Committed |

New Hampshire | ||

| Richard Gridley | Suffolk | 1631 | Boston | Brickmaker | Disarmed Disfranchised Acknowledged error |

||

| Hugh Gunnison | before 1635 | Boston | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||||

| Atherton Hough | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Boston | Gentleman | Rejected as Deputy | ||

| Benjamin Hubbard | before 1634 | Charlestown | Surveyor | Acknowledged error | |||

| Ralph Hudson | Yorkshire | 1635 | Boston | Draper | Acknowledged error | ||

| Robert Hull | Leicestershire | 1635 | Boston | Blacksmith | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| Samuel Hutchinson | Lincolnshire | 1637 | Boston | Denied residence | Portsmouth Exeter |

Brother of William Hutchinson | |

| James Johnson | Northamptonshire | before 1636 | Boston | Leather dresser Glover |

Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| Matthew Jyans | Essex | 1630 | Boston | Servant | Disarmed | ||

| William King | Dorset | 1634 | Salem | Disarmed | |||

| William Larnet | Surrey | 1634 | Charlestown | Committeeman | Acknowledged error | ||

| Thomas Leverett | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Boston | ||||

| William Litherland | London | 1633 | Boston | Carpenter | Disarmed | ||

| Thomas Marshall | Lincolnshire | before 1634 | Boston | Ferryman | Disarmed Disfranchised |

||

| Thomas Matson | London | 1630 | Boston | Gunsmith | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| Edward Mellows | Bedford | 1630 | Charlestown | Farmer | Acknowledged error | ||

| Oliver Mellows | Lincolnshire | before 1633 | Boston | Disarmed | |||

| Robert Moulton | Surrey | 1628 | Salem | Shipwright | Disarmed | ||

| Ralph Mousall | London | 1630 | Charlestown | Carpenter | Dismissed from court Acknowledged error |

||

| John Odlin | London | 1630 | Boston | Cutler | Dismissed Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| John Oliver | Gloucestershire | 1630 | Boston | Surveyor | Disarmed Dismissed Acknowledged error |

||

| Thomas Oliver | Gloucestershire | 1630 | Boston | Surgeon | Disarmed | ||

| William Pell | before 1634 | Boston | Tallow chandler | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Edward Rainsford | 1630 | Boston | Cooper | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Robert Rice | Suffolk | 1630 | Boston | Disarmed Acknowledged error |

|||

| Ezekiel Richardson | Hertfordshire | 1630 | Charlestown | Farmer? | Acknowledged error | ||

| William Salter | Suffolk | before 1635 | Boston | Fisherman | Disarmed | ||

| Thomas Scruggs | Norfolk | 1628 | Salem | Disarmed | |||

| Samuel Sherman | Essex | before 1636 | Boston | Farmer? | Disarmed | ||

| Richard Sprague | Dorset | 1628 | Charlestown | Acknowledged error | |||

| William Townsend | Suffolk | before 1634 | Boston | Servant Baker |

Disarmed Acknowledged error |

||

| Gamaliel Wayte | Berkshire | 1630 | Boston | Servant | Disarmed | ||

| Thomas Wheeler | Berkshire | 1635 | Boston | Tailor | Disarmed | ||

| Thomas Wilson | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Roxbury | Miller | Excommunicated | Exeter | |

| William Wilson | Lincolnshire | 1635 | Boston | Joiner | Disarmed | ||

Peripheral group

This group consists of people who were not directly involved in the Antinomian controversy but who left the Massachusetts Colony because of family, social, or economic ties with others who left, or because of their religious affiliations. Some were servants of members of the core group, some were siblings, and some had other connections. Several of these men returned to Massachusetts.[139]

| Peripheral group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Place of origin | Year of arrival | Residence | Vocation | Disposition | Went to | Comments |

| Nathaniel Adams | before 1638 | Weymouth | Dish turner | Newport, but returned | |||

| John Albro | Suffolk | 1634 | Boston | Servant | Portsmouth | Servant of William Freeborn | |

| George Allen, Jr. | Somerset | 1635 | Weymouth | Boatman | Newport, but returned | ||

| Ralph Allen | Somerset | 1635 | Weymouth | Newport, but returned | |||

| Samuel Allen | Essex | before 1635 | Mount Wollaston | Sawyer | Newport, but returned | ||

| Richard Awarde | Bedford | 1629 | Boston | Portsmouth | |||

| William Baker | before 1636 | Watertown | Portsmouth | ||||

| George Barlow | before 1637 | Sandwich? | Exeter | ||||

| George Bates | 1635 | Boston | Thatcher | Dismissed | Exeter, but returned | ||

| Robert Bennett | before 1638 | Servant | Newport | ||||

| Townsend Bishop | before 1635 | Salem | Examined by clergy | ||||

| Jeremiah Blackwell | Lincolnshire | 1635 | Exeter (temp) | Anderson shows no record for this individual in New England[140] | |||

| John Briggs | 1635 | Watertown | Servant | Portsmouth | |||

| James Brown | 1630 | Charlestown | Denied signing | ||||

| Nicholas Brown | before 1638 | Portsmouth | |||||

| Erasmus Bullock | 1632 | Boston | Servant | Portsmouth, but returned | |||

| Richard Burden | before 1638 | Newbury | Portsmouth | Became a Quaker | |||

| John Burrows | Norfolk | 1637 | Salem | Cooper | Charged by court to keep silence | Had heretical tendencies | |

| Robert Carr | 1635 | Tailor | Portsmouth | ||||

| Jeremy Clarke | Kent | before 1638 | Watertown? | Portsmouth | Became a Quaker | ||

| John Clarke | Suffolk | 1630 | Ipswich | Portsmouth | |||

| Joseph Clarke | Suffolk | 1637 | Boston | Portsmouth | Brother of John Clarke | ||

| Thomas Clarke | Suffolk | 1637 | Boston | Portsmouth | Brother of John Clarke Became a Baptist | ||

| William Colburn | Essex | 1630 | Boston | ||||

| Edward Colcord | before 1637 | Salem | Dover | ||||

| William Cole | Somerset | before 1636 | Boston | Carpenter | Exeter | ||

| Thomas Cornell | Hertfordshire | before 1638 | Boston | Innkeeper | Portsmouth | Became a Quaker | |

| John Cramme | Lincolnshire | before 1635 | Boston | Farmer? | Exeter | ||

| James Davis | before 1638 | Servant | Portsmouth | ||||

| Nicholas Davis | Middlesex | 1635 | Charlestown | Tailor | Newport, but returned | ||

| Stephen Dummer | Hampshire | 1638 | (Transient) | Farmer? | Portsmouth, but returned | ||

| Thomas Dummer | Hampshire | 1638 | (Transient) | Portsmouth, but returned | |||

| Hugh Durdall | Hampshire | 1638 | (Transient) | Servant | Portsmouth | ||

| Robert Field | Hampshire | 1635 | Boston | Portsmouth | |||

| Gabriel Fish | Lincolnshire | before 1638 | Fisherman | Exeter (temp) | |||

| Robert Gilham | before 1637 | Boston | Mariner | Portsmouth | |||

| Samuel Gorton | London | 1636 | Plymouth | Clothier | Portsmouth | Leader of Gortonist sect | |

| Jeremy Gould | Hertfordshire | before 1637 | Weymouth | Portsmouth, but returned | |||

| Job Hawkins | Huntington | 1635 | Ipswich | Servant | Portsmouth | ||

| Thomas Hazard | 1635 | Boston | Ship Carpenter | Portsmouth | |||

| Christopher Helme | Surrey | 1637 | Follower of Gorton | ||||

| Enoch Hunt | Buckinghamshire | before 1638 | Weymouth | Blacksmith | Newport, but returned | ||

| Robert Jeffrey | 1635 | Charlestown | Portsmouth | ||||

| John Johnson | before 1638 | Mount Wollaston | Servant | Banished | Newport | Servant of William Coddington | |

| Christopher Lawson | Lincolnshire | 1637 | Boston | Cooper | Exeter, but returned | ||

| George Lawton | Bedfordshire | before 1638 | Boston | Portsmouth | |||

| John Layton | before 1638 | Ipswich | Newport, but returned | ||||

| Thomas Leavitt | Lincolnshire | 1637 | (Transient) | Exeter | |||

| Robert Lenthall | Surrey | before 1638 | Weymouth | Clergyman | Portsmouth | ||

| John Leverett | Lincolnshire | 1633 | Boston | ||||

| Edmund Littlefield | Hampshire | 1638 | (Transient) | Exeter | |||

| Francis Littlefield | Hampshire | 1638 | (Transient) | Exeter, but returned | |||

| John Maccumore | before 1638 | Plymouth | Carpenter | Newport, but returned | |||

| Thomas Makepeace | Northamptonshire | before 1635 | Dorchester | Gentleman; farmer | |||

| Christopher Marshall | before 1634 | Boston | Dismissed | Exeter | |||

| John Marshall | before 1638 | Boston | Servant | Portsmouth, but returned | |||

| Richard Maxson | before 1634 | Boston | Blacksmith | Portsmouth | |||

| Griffin Montague | before 1635 | Boston | Carpenter | Exeter | |||

| Adam Mott | Cambridge | 1635 | Hingham Roxbury |

Tailor | Portsmouth | ||

| Adam Mott, Jr. | Hampshire | 1638 | Newbury | Tailor | Portsmouth | ||

| John Mott | Cambridge | 1635 | Portsmouth | ||||

| Nicholas Needham | 1636 | Boston | Exeter | ||||

| William Needham | before 1638 | Boston | Newport, but returned | ||||

| George Parker | 1635 | Carpenter | Portsmouth | ||||

| Nicholas Parker | 1633 | Roxbury | Farmer? | Disarmed Denied signing |

|||

| John Peckham | Kent | before 1638 | Newport | Became a Baptist | |||

| James Penniman | Essex | 1630 | Boston | Disarmed Denied signing |

|||

| Thomas Pettit | 1633 | Boston | Servant | Exeter | |||

| Edward Poole | Somerset | 1634 | Weymouth | Sawyer | Newport, but returned | ||

| Philemon Pormont | Lincolnshire | before 1634 | Boston | School master | Dismissed | Exeter, but returned | |

| William Quick | before 1636 | Charlestown | Ship master | Newport | |||

| Robert Randoll | before 1638 | Mount Wollaston | Servant | Cited to appear before court | Servant of William Coddington | ||

| Robert Reade | before 1634 | Boston | Leather sealer | Exeter | |||

| Edward Rishworth | Lincolnshire | 1637 | (Transient) | Exeter | |||

| James Rogers | London | 1623 | Plymouth | Miller | Portsmouth | ||

| Sampson Salter | Oxford | 1635 | Fisherman | Newport | |||

| Thomas Savorie | Wiltshire | 1633 | Ipswich | Newport | |||

| Richard Searle | before 1637 | Dorchester | Servant | Newport, but returned | |||

| Sampson Shotten | Leicestershire | before 1636 | Mount Wollaston | Portsmouth | Follower of Gorton | ||

| Thomas Stafford | Warwickshire | 1626 | Plymouth | Newport | |||

| Anthony Stanyon | 1635 | Boston | Glover | Exeter, but returned | |||

| Augustine Storre | Lincolnshire | 1637 | (Transient) | Exeter | |||

| John Thornton | before 1638 | Boston | Portsmouth | Became a Baptist | |||

| John Vaughan | before 1633 | Watertown | Newport | ||||

| Thomas Waite | Essex | before 1635 | Ipswich | Portsmouth | |||

| Richard Wayte | before 1634 | Boston | Tailor | Disarmed Denied signing |

|||

| William Wenbourne | before 1635 | Boston | Farmer? | Exeter, but returned | |||

| William Wentworth | Lincolnshire | 1637 | (Transient) | Sawmill proprietor | Exeter | ||

| Francis Weston | 1637 | Salem | Banished | Providence | Baptist, then follower of Gorton | ||

| Michael Williamson | Bedford | 1635 | Ipswich | Locksmith | Portsmouth | ||

See also

References

- Hall 1990, p. 3.

- Anderson 2003, pp. 481–482.

- Anderson 2003, p. 482.

- Winship 2005, p. 4.

- Battis 1962, p. 6.

- Winship 2002, p. 6.

- Winship 2002, pp. 50–51.

- Winship 2002, pp. 5-9.

- Hall 1990, p. ix.

- Hall 1990, p. x.

- Hall 1990, p. 5.

- Bremer 1981, p. 4.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 86.

- Hall 1990, p. xi.

- St. Irenaeus, Adv. haer III 1 ; IV 35, 8

- http://thecripplegate.com/strange-fire-the-puritan-commitment-to-sola-scriptura-steve-lawson/

- http://thecripplegate.com/strange-fire-the-puritan-commitment-to-sola-scriptura-steve-lawson/

- Battis 1962, p. 111.

- John Wheelwright.

- Bell 1876, p. 2.

- Noyes, Libby & Davis 1979, p. 744.

- Dictionary of Literary Biography 2006.

- Winship 2005, pp. 18–19.

- Battis 1962, p. 113.

- Battis 1962, p. 114.

- Hall 1990, pp. 1–22.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 85.

- Battis 1962, p. 29.

- Champlin 1913, p. 3.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 97.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 99.

- Winship 2002, p. 50.

- Winship 2002, p. 7.

- Hall 1990, p. 4.

- Battis 1962, pp. 1–2.

- Hall 1990, p. 6.

- Winship 2002, pp. 64-69.

- Hall 1990, p. 152.

- Hall 1990, p. 7.

- Hall 1990, p. 8.

- Hall 1990, p. 153.

- Hall 1990, p. 9.

- Battis 1962, p. 161.

- Battis 1962, p. 162.

- Battis 1962, pp. 174–175.

- Battis 1962, p. 175.

- Battis 1962, p. 180.

- Battis 1962, p. 181.

- Battis 1962, p. 182.

- Battis 1962, p. 183.

- Battis 1962, p. 184.

- Battis 1962, pp. 184–185.

- Battis 1962, p. 186.

- Battis 1962, p. 187.

- Battis 1962, pp. 188–189.

- Hall 1990, p. 311.

- Battis 1962, pp. 189–190.

- Battis 1962, p. 190.

- Battis 1962, pp. 194–195.

- Battis 1962, p. 195.

- Battis 1962, p. 196.

- Winship 2002, p. 173.

- Winship 2002, p. 175.

- Winship 2002, p. 176.

- Morris 1981, p. 62.

- Battis 1962, p. 204.

- Battis 1962, p. 206.

- Battis 1962, p. 208.

- Battis 1962, p. 211.

- Battis 1962, p. 212.

- Battis 1962, p. 225.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 158.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 159.

- Battis 1962, p. 227.

- Battis 1962, p. 228.

- Battis 1962, p. 230.

- Battis 1962, p. 231.

- Battis 1962, p. 235.

- Battis 1962, p. 242.

- Battis 1962, p. 243.

- Battis 1962, p. 244.

- Battis 1962, pp. 246–7.

- Battis 1962, p. 247.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 208.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 212.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 228.

- Anderson 2003, pp. 479–481.

- Champlin 1913, p. 11.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 237.

- Roberts 2009, pp. 365–366.

- Bell 1876, pp. 149–224.

- Puritan Divines.

- Hall 1990, p. 396.

- Williams 2001, pp. 1–287.

- Adamson & Folland 1973, pp. 292–319.

- Ireland 1905, pp. 245–350.

- Adams 1894, p. 12.

- Hall 1990, p. 1.

- Hall 1990, pp. 326–327.

- Adams 1894, p. 15.

- Adams 1894, p. 16.

- Adams 1894, p. 19.

- Adams 1894, p. 20.

- Bell 1876, pp. 52-53.

- Adams 1894, pp. 235–284.

- Hall 1990, pp. 311–48.

- Upham 1835, pp. 122–140.

- Ellis 1845, pp. 169–376.

- Palfrey 1858, pp. 471–521.

- Anderson 2003, p. 484.

- Hall 1990, pp. i-xviii.

- Battis 1962, pp. 300–328.

- Battis 1962, pp. 300–307.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 1999, p. 23.

- Anderson 1995, p. 55.

- Anderson 1995, p. 218.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 1999, p. 465.

- Anderson 1995, p. 395.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 170.

- Anderson 1995, p. 588.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 557.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 2001, p. 573.

- Anderson 2003, p. 159.

- Anderson 1995, p. 855.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1052.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1293.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1501.

- Anderson 2007, p. 500.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1626.

- Anderson 2009, p. 187.

- Anderson 2009, p. 428.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1859.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1906.

- Anderson 2011, p. 236.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1922.

- Anderson 1995, p. 1986.

- Battis 1962, pp. 308–316.

- Austin 1887, p. 45.

- Battis 1962, pp. 317–328.

- Anderson, Sanborn & Sanborn 1999, p. 319.

Bibliography

- Adams, Charles Francis (1894). Antinomianism in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1636–1638. The Prince Society. p. 175.

Antinomianism in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Adamson, J. H; Folland, H. F (1973). Sir Harry Vane: His Life and Times (1613–1662). Boston: Gambit. ISBN 978-0-87645-064-2. OCLC 503439406.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins, Immigrants to New England 1620–1633. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-044-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Robert C.; Sanborn, George F. Jr.; Sanborn, Melinde L. (1999). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. I A–B. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-110-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Robert C.; Sanborn, George F. Jr.; Sanborn, Melinde L. (2001). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. II C-F. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-120-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Robert Charles (2003). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. III G-H. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-158-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)