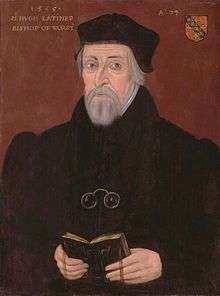

Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer (c. 1487 – 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester before the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary he was burned at the stake, becoming one of the three Oxford Martyrs of Anglicanism.

The Right Reverend Hugh Latimer | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Worcester | |

| |

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Worcester |

| In office | 1535–1539 |

| Predecessor | Girolamo Ghinucci |

| Successor | John Bell |

| Other posts | Chaplain to the Royal Household |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 15 July 1515 |

| Consecration | 1535 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1487 Thurcaston, Leicestershire, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 16 October 1555 (aged 67-68) Oxford, Oxfordshire, Kingdom of England |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Anglicanism |

| Education | University of Cambridge |

| Alma mater | Clare College |

Life

Latimer was born into a family of farmers in Thurcaston, Leicestershire. His birthdate is unknown. Contemporary biographers including John Foxe placed the date somewhere between 1480 and 1494. He started his studies in Latin grammar at the age of four, but not much else is known of his childhood. He attended the University of Cambridge and was elected a fellow of Clare College on 2 February 1510.[1] He received the Master of Arts degree in April 1514 and he was ordained a priest on 15 July 1515. In 1522, Latimer was nominated to the positions of university preacher and university chaplain. While carrying out his official duties, he continued with theological studies and received the Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1524. The subject of his disputation for the degree was a refutation of the new ideas of the Reformation emerging from the Continent, in particular the doctrines of Philipp Melanchthon.[2] Up to this time, Latimer described himself as "obstinate a papist as any was in England". A recent convert to the new teachings, Thomas Bilney heard his disputation and later came to him to give his confession.[3] Bilney's words had a great impact on Latimer and from that day forward he accepted the reformed doctrines.[4]

Latimer joined a group of reformers including Bilney and Robert Barnes that met regularly at the White Horse Tavern. He began to preach publicly on the need for the translation of the Bible into English. This was a dangerous move as the first translation of the New Testament by William Tyndale had recently been banned. In early 1528, Latimer was called before Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and he was given an admonition and a warning. The following year, Wolsey fell from Henry VIII's favour when he failed to expedite the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon. In contrast, Latimer's reputation was in the ascendant as he took the lead among the reformers in Cambridge. During Advent in 1529, he preached his two "Sermons on the Card" at St Edward's Church.[5]

In 1535, he was appointed Bishop of Worcester, in succession to an Italian absentee, and promoted reformed teachings and iconoclasm in his diocese. On 22 May 1538, at the insistence of Cromwell,[6] he preached the final sermon before Franciscan Friar John Forest was burnt at the stake, in a fire said to have been fueled partly by a Welsh image of Saint Derfel. In 1539, he opposed Henry VIII's Six Articles, with the result that he was forced to resign his bishopric and imprisoned in the Tower of London (where he was again in 1546).

He then served as chaplain to Katherine Duchess of Suffolk. However, when Edward VI's sister Mary I came to the throne, he was tried for his beliefs and teachings in Oxford and imprisoned. In October 1555 he was burned at the stake outside Balliol College, Oxford.

Trial

On 14 April 1554 commissioners from the papal party (including Edmund Bonner and Stephen Gardiner) began an examination of Latimer, Ridley, and Cranmer. Latimer, hardly able to sustain a debate at his age, responded to the council in writing. He argued that the doctrines of the real presence of Christ in the mass, transubstantiation, and the propitiatory merit of the mass were unbiblical. The commissioners tried to demonstrate that Latimer did not share the same faith as eminent Fathers, to which Latimer replied, "I am of their faith when they say well... I have said, when they say well, and bring Scripture for them, I am of their faith; and further Augustine requireth not to be believed."[7]

Latimer believed that the welfare of souls demanded he stand for the Protestant understanding of the gospel. The commissioners also understood that the debate involved the very message of salvation itself, by which souls would be saved or damned:

After the sentence had been pronounced, Latimer added, 'I thank God most heartily that He hath prolonged my life to this end, that I may in this case glorify God by that kind of death'; to which the prolocutor replied, 'If you go to heaven in this faith, then I will never come hither, as I am thus persuaded.'[8]

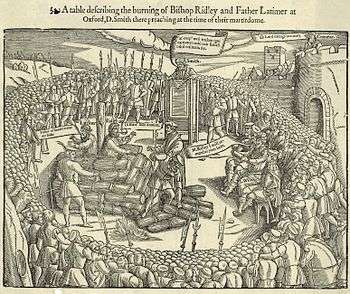

Death

Latimer was burned at the stake along with Nicholas Ridley. He is quoted as having said to Ridley:

Play the man, Master Ridley; we shall this day light such a candle, by God's grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.[9]

The deaths of Latimer, Ridley and later Cranmer – now known as the Oxford Martyrs – are commemorated in Oxford by the Victorian Martyrs' Memorial which is located near the actual execution site which is marked by a cross in Broad Street (then the ditch outside the city's North Gate).

Hugh Latimer said, "It may come in my days, old as I am, or in my children's days, the saints shall be taken up to meet Christ in the air, and so shall come down with Him again" (cf. 1 Thessalonians 4).

Commemoration

Latimer is honoured together with Nicholas Ridley in the Church of England and in the Episcopal Church (USA) on 16 October, and commemorated by the Anglican Church of Canada on that date.[10] The Latimer room in Clare College, Cambridge is named after him, as is a square, Latimer Square, in central Christchurch, New Zealand.

Notes

- "Latimer, Hugh (LTMR510H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Chester 1978, pp. 2–9

- Brown 1998, p. 58

- Chester 1978, pp. 16–18

- Chester 1978, pp. 34–39

- Demaus, Robert. (1904) Hugh Latimer: a biography. Religious Tract Society, London, United Kingdom. Page 295

- Robert Demaus, Hugh Latimer (1904), 506.

- Robert Demaus, Hugh Latimer (1904), 508.

- This is quoted in Actes and Monuments by John Foxe, but not in the first edition, in which he says that what Ridley and Latimer said to each other, "I can learn from no man." Tom Freeman posits that someone reported these words to Foxe, who seized upon them with alacrity. "Text, Lies and Microfilm," Sixteenth Century Journal XXX [1999], 44.

- "The Calendar". 16 October 2013.

References

This entry includes public domain text originally from the 1890 Pronouncing Edition of the Holy Bible (Biographical Sketches of the Translators and Reformers and other eminent biblical scholars).

- Chester, Allan G. (1978), Hugh Latimer: Apostle to the English, New York: Octagon Books, OCLC 3933258. Reprint of edition published by University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1954.

- Brown, Raymond (1998), The message of Nehemiah : God's servant in a time of change, Leicester, England Downers Grove, Ill: Inter-Varsity Press, ISBN 978-0-85111-580-1, OCLC 39281883

- Darby, Harold S. (1953), Hugh Latimer, London: Epworth Press, OCLC 740084.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1996), Thomas Cranmer: A Life, London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-06688-0.

- Wabuda, Susan (2004), "Latimer, Hugh (c.1485–1555)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Wabuda, Susan. "Latimer, Hugh (c.1485–1555)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16100. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hugh Latimer |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hugh Latimer. |

- Works by Hugh Latimer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hugh Latimer at Internet Archive

- Hugh Latimer - Protestant Martyr

- Foxe, John. . The Book of Martyrs – via Wikisource.

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Girolamo Ghinucci |

Bishop of Worcester 1535–1539 |

Succeeded by John Bell |