Francis Marbury

Francis Marbury (sometimes spelled Merbury) (1555–1611) was a Cambridge-educated English cleric, schoolmaster and playwright. He is best known for being the father of Anne Hutchinson, considered the most famous English woman in colonial America, and Katherine Marbury Scott, the first known woman to convert to Quakerism in the United States.

Francis Marbury | |

|---|---|

| Born | Baptised 27 October 1555 London, England |

| Died | February 1611 London, England |

| Other names | Francis Merbury |

| Education | Christ's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Cleric, schoolmaster |

| Spouse(s) | (1) Elizabeth Moore (2) Bridget Dryden |

| Children | (1st wife) Mary, Susan, Elizabeth; (2nd wife) Mary, John, Anne, Bridget, Francis, Emme, Erasmus, Anthony, Bridget, Jeremuth, Daniel, Elizabeth, Thomas, Anthony, Katherine |

| Parent(s) | William Marbury and Agnes Lenton |

Born in 1555, Marbury was the son of William Marbury, a lawyer from Lincolnshire, and Agnes Lenton. Young Marbury attended Christ's College, Cambridge, but is not known to have graduated, though he was ordained as a deacon in the Church of England in January 1578. He was given a ministry position in Northampton and almost immediately came into conflict with the bishop. Taking a position commonly used by Puritans, he criticised the church leadership for staffing the parish churches with poorly trained clergy and for tolerating poorly trained bishops. After serving two short jail terms, he was ordered not to return to Northampton, but disregarded the mandate and was subsequently brought before the Bishop of London, John Aylmer, for trial in November 1578. During the examination, Aylmer called Marbury an ass, an idiot and a fool, and sentenced him to Marshalsea prison for his impudence.

After two years in prison Marbury was considered sufficiently reformed to preach again and was sent to Alford in Lincolnshire, close to his ancestral home. Here he married and began a family, but again felt emboldened to speak out against the church leadership and was put under house arrest. Following a time without employment, he became desperate, writing letters to prominent officials, and was eventually allowed to resume preaching. Making good on his promise to curb his tongue, he preached uneventfully in Alford and with a growing prominence was rewarded with a position in London in 1605. He was given a second parish in 1608, which was exchanged for another closer to home a year later. He died unexpectedly in 1611 at the age of 55. With two wives Marbury had 18 children, three of whom matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford, and one of whom, Anne, became a puritan dissident in the Massachusetts Bay Colony who had a leading role in the colony's Antinomian Controversy.

Early life

Francis Marbury, born in London and baptised on 27 October 1555, was one of six children of William Marbury (1524–1581), and the youngest of three sons.[1][2] His father, who possibly attended Pembroke College, Cambridge in 1544, was a lawyer in Lincolnshire, a member of the Middle Temple, where he was admitted "specially ... at the instance of Mr. Francis Barnades" in May 1551, and still active until 1573;[3] he was elected Member of Parliament for Newport Iuxta Launceston in 1572.[4] His mother was Agnes, the daughter of John Lenton of Old Wynkill, Staffordshire according to historian John Champlin,[5] but genealogist Meredith Colket suggests that Lenton was from Aldwinkle in Northamptonshire, which is much closer to where the Marburys lived.[6] Marbury was likely educated in London, perhaps at St Paul's School, and he became well grounded in Latin as well as learning some Greek.[7] Though he was born and raised in London, his family maintained close ties with Lincolnshire. His older brother, Edward, was knighted there in 1603, and died in 1605 as the High Sheriff of Lincolnshire.[5]

Marbury matriculated at Christ's College, Cambridge in 1571, but is not known to have graduated.[8] He was ordained deacon by Edmund Scambler, Bishop of Peterborough, on 7 January 1578.[9] Though he was young when he became a deacon, he was not ordained as priest until 1605.[8] While Marbury was of the Church of England, he had decidedly Puritan views.[10] Not all English subjects thought that Queen Elizabeth had gone far enough to cleanse the English Church of Catholic rites and governance, or to ensure that its ministers were capable of saving souls through powerful preaching.[10] The most vocal of these critics were the Puritans, and Marbury was among the most radical of the non-conforming Puritans, the Presbyterians.[10] These more extreme non-conformists wanted to "abolish all the pomp and ceremony of the Church of England and remodel its government according to what they thought was the Bible's simple, consensual pattern."[10] To do this, they would eliminate bishops appointed by the monarchs, and introduce sincere Christians to choose the church's elders (or governors). The church leadership would then consist of two ministers, one a teacher in charge of doctrine, and the other a pastor in charge of people's souls, and also include a ruling lay leader.[10]

1578 trial

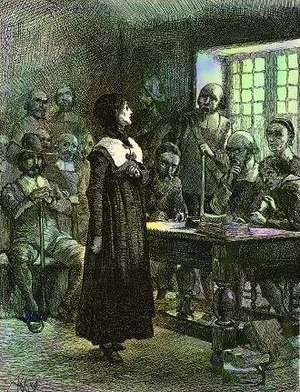

As a young man Marbury was considered to be a "hothead"[11] and felt strongly that the clergy should be well educated, and clashed with his superiors on this issue.[12] He spent time preaching at Northampton, but soon came into conflict with the bishop's chancellor, Dr James Ellis, who was on a mission to suppress any nonconforming clergy.[13] After two short imprisonments, Marbury was directed to leave Northampton and not return.[14] He disregarded this order, and was then brought to trial in the consistory court of St Paul's in London before the high commission on 5 November 1578. Here he was examined by the Bishop of London, John Aylmer, and by Sir Owen Hopton, Dr Lewis, and Archdeacon John Mullins.[15] Marbury made a transcript of this trial from memory and used it to educate and amuse his children, he being the hero, and the Bishop being portrayed as somewhat of a buffoon, and the transcript can be found in Benjamin Brook's study of notable Puritans.[15][16] Historian Lennam finds nothing in this transcript that is either "improbable or inconsistent with the Bishop's testy reputation."[17]

In the trial, Aylmer began the accusations of Marbury, saying "you had rattled the Bishop of Peterborough," to which Marbury accused the bishop of placing poorly trained ministers in the parish churches, adding that the bishops were poorly supervised. Aylmer then retorted, "The Bishop of Peterborough was never more overseen in his life than when he admitted thee to be a preacher in Northampton."[18] Marbury warned that for every soul damned by the lack of adequate preaching, the guilt "is on the bishops' hands."[10] To this Aylmer replied, "Thou takest upon thee to be a preacher, but there is nothing in thee. Thou art a very ass, an idiot, and a fool."[19]

As the examination continued, Aylmer considered the ability of the Church of England to put trained ministers in every parish. He barked, "This fellow would have a preacher in every parish church!" to which Marbury replied, "so would St. Paul."[20] Then Aylmer asked, "But where is the living for them?" To this Marbury answered, "A man might cut a large thong out of your hide, and that of the other prelates, and it would never be missed."[20][21] Having lost his patience, the bishop retorted, "Thou are an overthwart, proud, puritan knave." Marbury answered, "I am no puritan. I beseech you to be good to me. I have been twice in prison already, but I know not why.[22] To this, Aylmer was unsympathetic, and he rendered the sentence, "Have him to the Marshalsea. There he shall cope with the papists."[22] Marbury then threatened divine retribution upon the bishop by warning him to beware the judgements of God.[23] His daughter Anne Hutchinson would make a similar threat towards the magistrates and ministers at her civil trial before the Massachusetts Court, nearly 60 years later.[24]

Later life

For his conviction of heresy, Marbury spent two years in Marshalsea Prison, on the south side of the River Thames, across from London.[25] In 1580, at the age of 25, he was released and was considered sufficiently reformed to preach and teach, and moved to the market town of Alford in Lincolnshire, about 140 miles (230 km) north of London, near his ancestral home.[26] He was soon appointed curate (deputy vicar) of St Wilfrid's Church, Alford.[27] His father died in 1581, leaving Marbury with some welcome income as well as "lawe bookes and a ring of gold."[2]

Sometime about 1582 he married his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and in 1585 he became the schoolmaster at Alford Grammar School, free to the poor and founded under Queen Elizabeth.[5][28] Marbury is thought to have been the teacher or tutor of young John Smith, who became an early explorer and leader in the Jamestown Colony in Virginia.[29]

After bearing three daughters, Marbury's first wife died about 1586, and within a year of her death he married Bridget Dryden, about ten years younger than he, from a prominent Northamptonshire family.[30][31] Bridget was born in the Canons Ashby House in Northamptonshire, the daughter of John Dryden and Elizabeth Cope.[32][33] Her brother, Erasmus Dryden, was the grandfather of the playwright and Poet Laureate John Dryden.[33]

In 1590 Marbury once again felt emboldened to speak out against his superiors, denouncing the Church of England for selecting poorly educated bishops and poorly trained ministers.[34] The Bishop of Lincoln, calling him an "impudent Puritan," removed him from preaching and teaching, and put him under house arrest.[34] On 15 October 1590 Marbury wrote a letter to the statesman William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, who was the uncle of Marbury's acquaintance, Francis Bacon. In the letter he explained his religious creed and claimed that he was deprived of his preaching licence "for causes unknown to him."[35] Without employment, he tended his gardens and tutored his children, reading to them from his own writings, the Bible, and John Foxe's Book of Martyrs.[34] Somehow the family was able to survive, perhaps from borrowing from the Drydens.[36] While this suspension from preaching was thought to be short by historian Lennam, his daughter's biographer, Eve LaPlante, wrote that it lasted nearly four years.[34] Whichever the case, by 1594 he was once again preaching, and from this point forward, Marbury resolved to curb his tongue and not openly question those in positions of authority.[34]

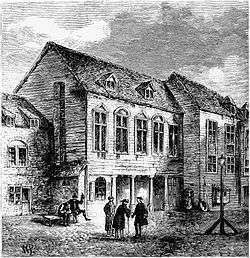

Following this final suspension, both his fame and fortune rose, and at one point Marbury became lecturer at St Saviour, Southwark.[37] In 1602 he was given the honour of delivering the "Spittle sermon" in London on Easter Tuesday, and again at St Paul's Cross in London in June.[38] The following year he had the distinction of delivering a special sermon on the accession of James I to the throne, and at this point several of his sermons were finding their way into print.[38] With the support of Richard Vaughan, the Bishop of London, he was moved to London in 1605,[39] finding a residence in the heart of the city where he was given the position of vicar of St Martin Vintry.[40] Here his Puritan views, though somewhat muffled, were nevertheless present and tolerated, since there was a shortage of pastors.[40][41]

London was a vibrant and cosmopolitan city, and active playwrights of the time were William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson, whose plays were performed just across the river.[42] The Marburys managed to avoid the bubonic plague that occasionally worked its way through the city.[42] Marbury took on additional work in 1608, preaching in the parish of St Pancras, Soper Lane, travelling there by horse twice a week.[42] In 1610 he was able to replace that position with one much closer to home, and became rector of St Margaret, New Fish Street, a short walk from St Martin Vintry.[42] Marbury died unexpectedly in February 1611, at the age of 55.[42] He had written his will in January 1611, and its brevity suggests that it was written in a hurry following a sudden and serious illness. The will mentions his wife by name and 12 living children, but only his daughter Susan, from his first marriage, is mentioned by name. His widow resided for a time at St Peter, Paul's Wharf, London, but about December 1620 she married Reverend Thomas Newman of Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and died in 1645.[43]

Works and legacy

Marbury's most noted work, The Contract of Marriage between Wit and Wisdom was written in 1579 while he was in prison.[35] It was a moral interlude or "wit play", following The Play of Wit and Science by John Redford, and an adaptation of its sequel The Marriage of Wit and Science.[44][45] The play was noted in 1590 as one of the "current plays of the time."[35] Author T. N. S. Lennam described the work as a "lusty, occasionally very coarse, short interlude in which the morality material is dominated by rather imitative farcical episodes more elementally entertaining than didactic."[46]

Marbury also helped write the preface to the works of other religious writers. One of these prefaces was written for Robert Rollock's A Treatise on God's Effectual Calling (1603), and another was for Richard Rogers' seminal work, Seven Treatises (1604).[47] In the latter, Marbury praised Rogers "for having delivered a crushing blow against the Catholics and thereby vindicating the Church of England."[48] This prefatory material summed up the puritan unitary vision for England: "one godly ruler, one godly church, and one godly path to heaven, with puritan ministers writing the guidebooks."[48]

While Marbury was not considered one of the great Puritan ministers of his day, he was nevertheless well known. Sir Francis Bacon called him "The Preacher," and recognised him as such in his 1624 work Apothegm. A leading minister of the time, Reverend Robert Bolton, expressed a considerable respect for Marbury's teachings.[49]

One negative aspect of Marbury's later career involved his time in Alford when he was the governor of the free grammar school there between 1595 and 1605. A 1618 court case pointed to Marbury's improper handling of the school's endowments, and following an inquisition, the surviving executors to Marbury's will were ordered to pay "certain sums unto the Governors" of the school as compensation.[50]

Family

Marbury was said to have 20 children, but only 18 have been identified, three with his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and 15 with his second wife, Bridget Dryden.[51][52] The three children from his first marriage were all girls, Mary (c. 1584–1585), Susan (baptised 12 September 1585; married a Mr Twyford) and Elizabeth (c. 1587–1601). His children with Bridget Dryden were Mary (born c. 1588), John (baptised 15 February 1589/90), Anne (baptised 20 July 1591), Bridget (baptised 8 May 1593; buried 15 October 1598), Francis (baptised 20 October 1594), Emme (baptised 21 December 1595), Erasmus (baptised 15 February 1596/7), Anthony (baptised 11 September 1598; buried 9 April 1601), Bridget (baptised 25 November 1599), Jeremuth (or Jeremoth, baptised 31 March 1601), Daniel (baptised 14 September 1602), Elizabeth (baptised 20 January 1604/5), Thomas (born c. 1606?), Anthony (born c. 1608), and Katherine (born c. 1610).[51][52]

Three of Marbury's sons, Erasmus, Jeremuth, and the second Anthony, all matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford.[51] His daughter Anne married William Hutchinson and sailed to New England in 1634, becoming a dissident Puritan minister at the centre of the Antinomian Controversy, and was, according to historian Michael Winship, "the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history."[53] His only other child to emigrate was his youngest child, Katherine, who married Richard Scott and settled in Providence in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Katherine and her husband were at times Puritans, Baptists, and Quakers, and Katherine was whipped in Boston for confronting Governor John Endecott over his persecution of Quakers and supporting her future son-in-law Christopher Holder who had his right ear cut off for his Quaker evangelism.[54]

Marbury's sister, Catherine, married in 1583 Christopher Wentworth, and they became grandparents of William Wentworth who followed Reverend John Wheelwright to New England, and eventually settled in Dover, New Hampshire, becoming the ancestor of many men of prominence.[5][55]

Ancestry

In 1914, John Champlin published the bulk of the currently known ancestry of Francis Marbury.[56] Most of the material in the following ancestor chart is from Champlin, supplemented by genealogist Meredith Colket.[57] The Williamson line was published in The American Genealogist by F. N. Craig in 1992,[58] while an online source, cited within, covers the Angevine line. An online source giving the ancestry of Agnes Lenton[59] is incorrect based on Walter Davis' research published in the New England Historic Genealogical Register in 1964.[60]

| Ancestors of Francis Marbury | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Colket 1936, p. 27.

- Lennam 1968, p. 209.

- William Marbury 2012.

- Fuidge, N. M. "MARBURY, William (1524-81), of the Middle Temple, London and ?of Girsby, Lincs". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Champlin 1914, p. 23.

- Colket 1936, p. 12.

- Lennam 1968, p. 210.

- Venn Library.

- Colket 1936, p. 28.

- Winship 2005, p. 7.

- Collinson 1967, p. 433.

- Bremer 1981, p. 1.

- Lennam 1968, p. 211.

- Brook 1813, pp. 223–6.

- Brook 1813, p. 223.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 19.

- Lennam 1968, p. 212.

- Brook 1813, p. 225.

- Brook 1813, p. 226.

- Brook 1813, p. 227.

- Foster 1996, p. 55.

- Brook 1813, p. 228.

- Winship 2005, p. 8.

- Winship 2002, p. 178.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 26.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 27.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 29.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 30.

- Firstbrook 2014, pp. 117–119.

- Lennam 1968, p. 215.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 31.

- Champlin 1914, p. 24.

- Winship 2005, p. 9.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 33.

- Colket 1936, p. 29.

- Crawford 1970, p. 13.

- Greaves 1981, p. 353.

- Lennam 1968, p. 217.

- Rugg 1930, p. 7.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 34.

- Bremer 1981, p. 2.

- LaPlante 2004, p. 37.

- Colket 1936, p. 32.

- Harbage & Schoenbaum 1989, p. 48.

- Interludes and Modern Society 2010.

- Lennam 1968, p. 207.

- Lennam 1968, p. 218.

- Winship 2002, p. 15.

- Colket 1936, p. 30.

- Lennam 1968, p. 219.

- Champlin 1914, pp. 23–24.

- Colket 1936, pp. 33–34.

- Winship 2005, p. 1.

- Austin 1887, p. 272.

- Noyes, Libby & Davis 1979, p. 738.

- Champlin 1914, p. 18.

- Colket 1936, p. 22.

- Anderson 2003, p. 484.

- Rootsweb.

- Davis 1964, p. 259.

- Register Report--Angevine.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert Charles (2003). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. III G-H. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-158-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bremer, Francis J. (1981). Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-89874-063-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brook, Benjamin (1813). The Lives of the Puritans Containing a Biographical Account of Those Divines who Distinguished Themselves in the Cause of Religious Liberty, from the Reformation Under Queen Elizabeth to the Act of Uniformity in 1662. 1. London: printed for James Black. pp. 223–228.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Champlin, John Denison (1914). "The Ancestry of Anne Hutchinson". New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. XLV: 17–26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colket, Meredith B. (1936). The English Ancestry of Anne Marbury Hutchinson and Katherine Marbury Scott. Philadelphia: Magee Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collinson, Patrick (1967). The Elizabethan Puritan Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crawford, Deborah (1970). Four Women in a Violent Time. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Walter G. (October 1964). Shepherd of Littlecote. New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 118. New England Historic Genealogical Society. pp. 251–262. ISBN 978-0-7884-0293-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Firstbrook, Peter (2014). Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Founding of America. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster, Stephen (1996). The Long Argument: English Puritanism and the Shaping of New England Cutlture, 1570–1700. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1951-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greaves, Richard L. (1981). Society and Religion in Elizabethan England. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1030-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harbage, Alfred; Schoenbaum, S. (1989). Annals of English Drama 975-1700. London: Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- LaPlante, Eve (2004). American Jezebel, the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-056233-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lennam, T. N. S. (April 1968). "Francis Merbury, 1555–1611". Studies in Philology. 65 (2): 207–222. JSTOR 4173603.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Noyes, Sybil; Libby, Charles Thornton; Davis, Walter Goodwin (1979). Genealogical Dictionary of Maine and New Hampshire. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rugg, Winnifred King (1930). Unafraid: A Life of Anne Hutchinson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winship, Michael Paul (2002). Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636–1641. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08943-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winship, Michael Paul (2005). The Times and Trials of Anne Hutchinson: Puritans Divided. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1380-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online sources

- Behling, Sam. "Register Report--Angevine". Rootsweb at Ancestry.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Francis Marbury". Venn Library. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Selected Families and Individuals". Rootsweb at Ancestry.com. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Theatre: Interludes and Early Modern Society". Worldtrade Arts. 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- "William Marbury (1524–81)". The History of Parliament. 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

Further reading

- Marbury, Francis, The Marriage Between Wit and Wisdom (1971), Malone Society Reprint Series, No. 125

- M'Clure, A. W. (1870). The Lives of John Wilson, John Norton, and John Davenport. Boston: Andover Theological Institute(?).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) see p 20

- Richardson, Douglas; Everingham, Kimball G. (2004). Plantagenet Ancestry. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. pp. 492–3. ISBN 978-0-8063-1750-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)