Another Mother for Peace

Another Mother for Peace (AMP) is a grass-roots anti-war advocacy group founded in 1967 in opposition to the U.S. war in Vietnam.[1][2][3] The association is “dedicated to eliminating the use of war as a means of solving disputes among nations, people and ideologies. To accomplish this, they seek to educate citizens to take an active role in opposing war and building peace.” [4]

Origins

The inspiration for Another Mother for Peace came out of a child's first birthday in 1967. Barbara Avedon, a former writer for The Donna Reed Show who would later co-create the series Cagney and Lacey, had invited friends to her southern California home to celebrate the birthday of her son, Josh. Opposed to U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, Avedon expressed her fear that she could be raising her son only to send him off to war.[5] She and others present agreed that they wanted to take some action.[6]

In February [7] or March,[1] 1967, 15 women met in Avedon's living room to talk about ways they could work together to help bring an end to the war. “We wanted to... communicate our horror and disgust to our elected representatives in one concerted action,” Avedon later wrote. “We were not ‘bearded, sandaled youths,’ ‘wild-eyed radicals’ or dyed in the wool ‘old line freedom fighters’ and we wanted the Congress to know that they were dealing with an awakening and enraged middle class.”[8]

AMP’s first action was a Mother's Day campaign in opposition to the Vietnam War. Their plan was to send then-President Lyndon B. Johnson and members of Congress Mother's Day cards expressing their yearning for peace.[7][9]

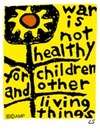

Los Angeles artist Lorraine Art Schneider donated the use of a striking illustration for the Mother's Day peace cards--a sunflower on yellow background amid the slogan “War is not healthy for children and other living things.” [1]

The Mother's Day card featured Schneider's sunflower design on the front. Inside was this text:

For my Mother's Day gift this year,

I don't want candy or flowers.

I want an end to killing.

We who have given life

must be dedicated to preserving it.

Please talk peace.[10]

The yellow-and-black logo proved instantly popular.[7] The initial printing of 1000 cards soon sold out.[1] By the end of May 1967, 200,000 of the Mother's Day cards had been sold.[1][9] Members of Congress were “flooded” with cards, and Senator J. William Fulbright was photographed at his desk among piles of the AMP cards.[11] The logo was also used in jewelry, posters, pamphlets, bumper stickers and other items.[10] The distinctive calligraphy associated with AMP materials was produced by in-house designer Gerta Katz.[12][13]

Another Mother for Peace's reliance on middle class respectability and their maternalist peace rhetoric linked the efforts of Another Mother for Peace's members to a long history of women's peace activism, from Women Strike for Peace to Julia Ward Howe's efforts to create Mother's Day.[14]

AMP's Vietnam War-era activities

AMP's founding mission was "to educate women to take an active role in eliminating war as a means of solving disputes between nations, people and ideologies." [1] Through its newsletters, AMP gave “peace homework” to its members, offering concrete ideas for action against the war and war in general. AMP opposed anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs), chemical warfare, biological warfare and multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), which contained multiple warheads on a single missile cone, thereby evading SALT limitations. Revenues from the sale of items imprinted with the sunflower logo supported AMP's Invest in Peace fund; the fund supported congressmen who advocated for withdrawal from Vietnam and who opposed ABMs and MIRVs. AMP sought to demonstrate a link between U.S. war policy and oil interests, and pushed for investigation into U.S. oil leases off the coast of Vietnam. In 1971, co-chairmen Barbara Avedon and Dorothy B. Jones testified before the U.S. House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee in opposition to the military budget.[1]

AMP advocated for a U.S. Department of Peace that would examine nonmilitary alternatives to conflict resolution.[15] The group published a 56-page pamphlet by political scientist Frederick L. Schuman in support of House and Senate bills introduced in the 91st Congress, 1st Session (1969) proposing a cabinet level Department of Peace. The proposed department would train citizens for public service, invest in anti-poverty programs abroad, and assume management of certain agencies such as the Agency for International Development, the Peace Corps, the International Agricultural Development Service of the Department of Agriculture, and others. Schuman argued that the Department of State’s mission was to advance U.S. national interests, not to plan for peace, and “[p]eople get what they plan for...” [16] Schuman traced the idea for an American peace agency to Benjamin Banneker's Almanack of 1793.[17]

In its June 1970 newsletter, AMP launched a letter writing campaign targeting eight weapons manufacturers who also sold goods in the consumer market. The newsletter provided names and addresses for the presidents and board chairmen of the following eight corporations: Bulova Watch, Honeywell, General Electric, Westinghouse, Motorola, Whirlpool, General Motors and Dow Chemical. “Let's tell them where we're really at! ... We represent a lot of toasters - a lot of dollars - a lot of public opinion...” AMP's newsletter said.[18] The campaign's purpose was to pressure the manufacturers into ending their participation in the war industry by threatening to boycott their consumer products if they did not. According to a 1972 article analyzing the campaign, it was not effective because too few messages reached the target companies, and the targets were so numerous “that no one target was strongly affected by the campaign.” [19]

At a Mother's Day Assembly in Los Angeles in May 1969, AMP introduced The Pax Materna--“a permanent, irrevocable... understanding among mothers of the world:”

I join with my sisters in every land

In The Pax Materna—

A permanent declaration of peace

That transcends our ideological differences.

In the nuclear shadow, war is obsolete.

I will no longer suffer it in silence

Nor sustain it by complicity.

They shall not send my son

To fight another mother's son.

For now, forever, there is no mother

Who is an enemy to another mother.[10]

During the Vietnam war the AMP newsletter was sent to between 130,000 and 400,000 homes yearly. The organization produced two films: You Don’t Have to Buy War, Mrs. Smith and Another Family for Peace. [10] Paul Newman, Donna Reed, Debbie Reynolds and other celebrities made public appearances on behalf of AMP.[1]

AMP became less active as U.S. involvement in Vietnam declined. Though most activity had ceased by 1979, the AMP newsletter was published until 1985, at which time the office was closed. Another Mother for Peace's records from the organization's birth to 1985 have been in the care of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, since 1986.[1]

Notable members and supporters

Another Mother for Peace enjoyed active support from a number of well-known personalities. These include former Miss America Bess Myerson; and actors Debbie Reynolds, Joanne Woodward, Paul Newman, Dick van Dyke,[1] Lauren Bacall, Janice Rule, Whitney Blake and Donna Winters [6] Associated Press reporter George Zucker later described visiting the AMP office in the early years: “On the day I visited their rented office in Beverly Hills, actor Robert Vaughn, then star of the TV series, Man from U.N.C.L.E., sat at a long table stuffing envelopes. Actress Donna Reed worked beside him.” [6]

Rebirth

As the United States went to war in the early 21st century, Carol Schneider, daughter of Lorrainne Schneider, and Joshua Avedon, son of Barbara Avedon, revived the organization.[6] AMP operates as a not-for-profit, non-partisan, 501(c)(3) organization, offering "peace homework" and distributing educational materials, seeking to engage citizens in pursuing alternatives to armed conflict. Sales of posters and other materials with the sunflower logo support the group's efforts.[20]

References

- Archived 2008-11-23 at the Wayback Machine, Swarthmore College Peace Collection. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- Steiner, Nancy S. "The Little Flower That Could, Jewish Journal, October 16, 2003. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- "Vietnam Era Anti-War Group is Revived," Santa Monica Mirror, October 15–21, 2003. Accessed 15 November 2008.

- Archived 2008-12-27 at the Wayback Machine Another Mother for Peace home page. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- Zucker, George. "Mother of All Peace Protests," New Partisan May 13, 2006. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- "Vietnam Era Anti-War Group is Revived," Mirror, 2003. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Another Mother for Peace History page. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine AMP History page. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- AMP Mother's Day card page. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.

- "Center for the Study of Political Graphics". collection-politicalgraphics.org. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Historic Protest from 1960s and 1970s California". Hyperallergic. 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Moravec, Michelle (2010). "Another Mother for Peace: Reconsidering Maternalist Peace Rhetoric from an Historical Perspective 1967-2007". Journal of the Motherhood Initiative. 1 (1): 9–29.

- Schuman, Frederick L. Why a Department of Peace. Beverly Hills: Another Mother for Peace, 1969.

- Schuman, 1969, p.27.

- Schuman, 1969.

- Krieger, David M., "The Another Mother for Peace Consumer Campaign. A Campaign That Failed," Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1971), pp. 163-166. Retrieved on 11-15-2008.

- Krieger, 1971. Retrieved on 11-15-2008.

- Archived 2008-12-27 at the Wayback Machine AMP home page. Retrieved on 2008-11-15.