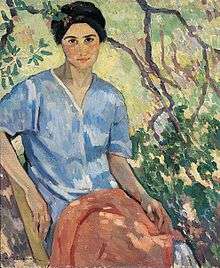

Anne Bremer

Anne Bremer (May 21, 1868 – October 26, 1923) was a California painter,[1] influenced by Post-Impressionism, who was called "the most 'advanced' artist in San Francisco" in 1912 after art studies in New York and Paris.[2] She was described in 1916 as “one of the strong figures among the young moderns”[3] and later as “a crusader for the modern movement.” [4] She had numerous solo exhibitions, including one in New York.

Life

Anne Milly[5] Bremer was born in San Francisco on May 21, 1868, to upper-middle-class German-Jewish immigrants Joseph and Minna Bremer. In 1880-81 she traveled in Europe with her parents, and they brought back a cousin, Albert Bender, from Dublin, Ireland, to live with them and work for another uncle, William Bremer. She studied art with Emil Carlsen at the San Francisco Art Students League and with Arthur Mathews and others at the California School of Design, Mark Hopkins Institute of Art, receiving a Certificate of Proficiency in 1898.[6] By the time she graduated she was on the board of the Sketch Club, an organization of San Francisco women artists, and she was its president at the time of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[7] Under her leadership the Sketch Club produced the first major art exhibition in the city after the disaster and enlarged its membership to include men.

She lived in Berkeley during 1907, attended summer classes at the University of California, and painted a series of East Bay landscapes. That year she also began exhibiting in the new gallery of California artists in the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey. After two years back in San Francisco, she moved to New York by January 1910, where she studied at the Art Students League. She sailed to Europe in mid-April 1910 and traveled, primarily in Italy, then settled in Paris, where she remained until September 1911 and studied at the Académie Moderne and Académie de la Palette.

After returning to San Francisco she had her first solo exhibition at the gallery of Vickery, Atkins & Torrey in March 1912 and another at the St. Francis Hotel in November–December 1912. While painting in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California during the summer of 1912, she met and befriended the artist Jennie V. Cannon, who used her own studio-gallery to stage the first exhibit of Bremer’s work on the Monterey Peninsula and hosted an opening-night banquet in her honor.[8]

By 1913 her home and studio were in the Studio Building on Post Street in San Francisco along with Albert Bender and various other artists. She evidently played a leadership role in developing the building with spaces for artists to live, work and exhibit.[9] In 1915 she had five works in the Panama Pacific International Exposition and received a bronze medal. Also in 1915, she was included in a three-person “Modern School” exhibition (with Henry Varnum Poor of Stanford and Jerome Blum of Chicago), at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art. Her work began appearing in California Art Club exhibitions that year. In 1916 she was elected secretary of the San Francisco Art Association, where she helped lead a major phase of growth in conjunction with the creation of an art museum at the Palace of Fine Arts. She had a solo show of 27 paintings at the Arlington Galleries in New York City in 1917 and participated in the Society of Independent Artists second annual exhibition in 1918.

Beginning in 1921 she was coping with leukemia. She gave up painting and turned to studying literature and writing poetry. She died in October 1923.

Style

Bremer’s work incorporates several elements associated with modern painting. Each of her paintings calls attention to itself as a flat surface holding an arrangement of colored paint, not as a literal representation or illusion of reality. Brushstrokes are broad and distinct from one another, sometimes with areas of unpainted canvas showing through. There is either very little suggestion of depth, or the perspective is distorted or ambiguous. Colors are bold and not always naturalistic. The subject might be figures, landscape, still life or a combination of these, but what was more important to the artist was creating a successful composition and emotional effect. Her works, while individualistic, are sometimes reminiscent of those of Robert Henri and Marsden Hartley, two of the major figures in modern American art. Hartley once wrote that in his opinion Anne Bremer was “one of the three artists of real distinction that California has produced.”[10]

Legacy

Following her death in 1923, Albert Bender established several memorials, including an award for art students and the Anne Bremer Memorial Library at the San Francisco Art Institute,[11] a marble chair in the Greek Theatre at the University of California, Berkeley, and an outdoor sculpture at Mills College. He also sponsored publication of a pair of limited edition books, The Unspoken and Other Poems and Tributes to Anne Bremer (Printed by John Henry Nash, 1927). Through Anne Bremer's influence and contacts with artists, Albert Bender was inspired to become an important patron of artists and art museums and a founder of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Mills College Art Museum.[12] Bremer and Bender are buried side by side in Home of Peace Cemetery, Colma, California.[13]

Solo exhibitions

- 1912 Vickery, Atkins and Torrey, San Francisco

- 1912 St. Francis Hotel, San Francisco

- 1913 Friday Morning Club, Los Angeles

- 1914 Helgesen Galleries, San Francisco

- 1916 Hill Tolerton Gallery, San Francisco

- 1917 Arlington Galleries, New York

- 1922 Print Rooms, San Francisco

- 1923 Memorial exhibitions, Print Rooms and San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts

Museum collections

- Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

- Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, CA

- Oakland Museum of California

- San Diego Museum of Art

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Notes

- "Anne M. Bremer (1868-1923)". George Stern Fine Arts.

- Porter Garnett, “News Notes of the Artist Folk,” San Francisco Call, 15 September 1912, p. 70.

- Laura Bride Powers, “News of Artists, Art and Studios,” Oakland Tribune, 26 November 1916, p. 34.

- Beatrice Judd Ryan, “The Rise of Modern Art in the Bay Area,” in California Historical Society Quarterly, v. 38 (1959), p. 2.

- Some sources spell her middle name "Millay," but an artist card in her own handwriting at the California State Library lists it as "Milly."

- "Anne Millay Bremer (1868-1923)". Trotter Galleries.

- Louis Stellman, “Local Artists Reestablishing Their Colony,” San Francisco Chronicle, 30 June 1907, p. 5.

- Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. p. 333. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-29. Retrieved 2016-06-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link))

- Reminiscences of Eric Spencer and Constance Macky. Berkeley, CA: Bancroft Library, Regional Oral History Office. 1954. p. 47.

- As quoted (or paraphrased) by Ruth Pielkovo, San Francisco Journal, April 2, 1922; original source unknown.

- "Anne Bremer Memorial Library". San Francisco Art Institute.

- "Our Mission". Mills College Art Museum.

- Find A Grave Memorials # 130104813 and 134124115, findagrave.com.

Selected bibliography

- Ruth Lilly Westphal, ed. (1986). Plein Air Painters of California: The North. ISBN 0961052015

- The Creative Frontier: A Joint Exhibition of Five California Jewish Artists, 1850-1928 (1975). Exhibition catalog, Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley, and Temple Emanu-El Museum, San Francisco.

- Gene Hailey, ed. (1937). California Art Research (WPA Project 2874, O.P. 65-3-3632), vol. 7, pp. 87–128. Retrieved on 5 March 2012.

- Phyllis Ackerman, "A Woman Painter With a Man's Touch," Arts and Decoration. April 1923, p. 20.

- Ray Boynton, "Ruth Armer's Caricature Dolls . . . ," San Francisco Chronicle. 17 September 1922, p. D4.

- "Anne Bremer Returns to Exhibit Work." San Francisco Chronicle. 9 April 1922, p. F8.

- Helen Appleton Read, [exhibition review]. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 4 November 1917.

- Blanche M. d'Harcourt, "In Anne Bremer's Studio." The Wasp (San Francisco). 23 June 1917.

- Alma May Cook, "Conservative Post Impressionist: Miss Bremer Has Applied American Good Sense to This Phase of French Art." Los Angeles Express. 25 January 1913.

- "Miss Anne M. Brewer [sic] Has Interesting Art Exhibit: Canvases Depict Scenes That Are Unique in Artists' World." San Francisco Chronicle. 24 March 1912, p. 30.